Here’s the pot. The actual f***ing pot from 8,000 years ago where archaeologists found the oldest known evidence of winemaking. It’s thought that large-capacity jars of this sort served as multi-purpose fermentation, aging, and serving vessels. Climatologists have even concluded that the ancient climate in the region where the pot was found is almost identical to that of the present-day climate of powerhouse wine region Montalcino.

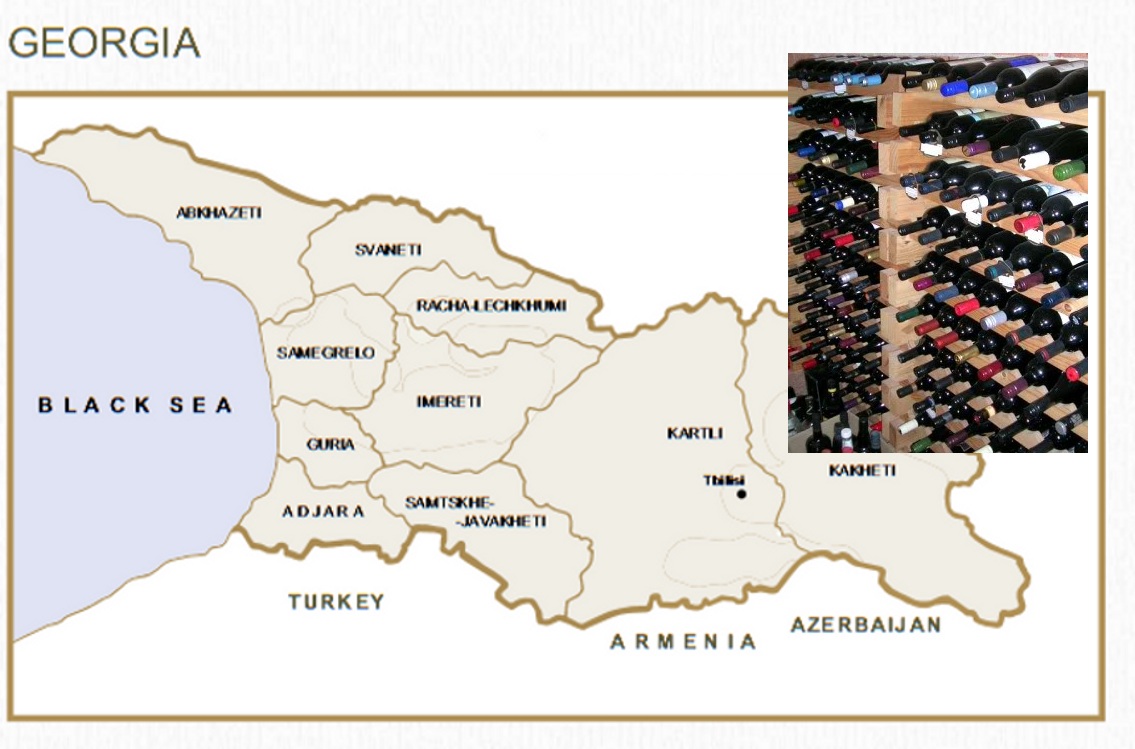

Being the country or culture to invent wine is massively significant culturally, historically, and economically. Georgia’s wine exports in recent years have increased in quantity, quality, and price according to the Georgian National Wine Agency. Over the last 3 years, the number of registered wineries has more than doubled to nearly 1,100 wineries as of this July, and Georgia’s increasing presence on the global stage can largely be attributed to the fact that it boasts the title of Inventor of Wine. Georgia received a record number of 8.7 million international visitors in 2018, of which nearly 5 million were tourists, a 16% increase from the year prior. Naturally, several countries – Armenia and Iran for instance – have been quarrelling and will certainly continue to quarrel over who has the right to the claim Inventor of Wine.

Being the country or culture to invent wine is massively significant culturally, historically, and economically. Georgia’s wine exports in recent years have increased in quantity, quality, and price according to the Georgian National Wine Agency. Over the last 3 years, the number of registered wineries has more than doubled to nearly 1,100 wineries as of this July, and Georgia’s increasing presence on the global stage can largely be attributed to the fact that it boasts the title of Inventor of Wine. Georgia received a record number of 8.7 million international visitors in 2018, of which nearly 5 million were tourists, a 16% increase from the year prior. Naturally, several countries – Armenia and Iran for instance – have been quarrelling and will certainly continue to quarrel over who has the right to the claim Inventor of Wine.

What is unique in Georgia is that while the wine export markets have become important economically the domestic market remains largely underdeveloped. The local wine culture in Georgia is deeply rooted and largely familial. We see and taste wines from the 1,100 registered commercial wineries. Georgians don’t; they drink their own, their parents’, their grandparents. Iago of Iago’s Winery shares that his wines are distributed exclusively to international markets – domestically, his wines are available only at the winery for him, his family, guests, and visitors. It’s actually quite uncommon for a Georgian to buy a bottle of wine. “It’s a big shame if you or your family don’t produce your own wine,” Mukhran had shared. There are over 100,000 family wineries according to Wines of Georgia – I don’t imagine they’re keeping a close count though.

The question “where was wine invented or discovered?” is actually a much more complicated one than it appears on the surface. For example, what if the wine was not purely grape wine but combined with other fermenting fruits or beer – does that count? And, answering the big question is more complicated still.

In search of the answer nonetheless, we haphazardly – riding in a janky two-decades-too-old Mercedes with no front bumper – make our way to the archaeological site in Marneuli about an hour south of Tbilisi, where the pot was found. The driver beams with pride for having been on-time. Communication is hazy at best through the language barrier, and Georgians aren’t known for being punctual. In fact, the Georgian punctuality chart looks something like this:

If you’re on-time, you’re way-too-early.

If you’re late, you’re early.

If you’re very late, you’re on-time.

And with this approach and a cheeky tongue, the Georgians earned from god the plot of land they now inhabit. The legend goes that when god was distributing land to the various peoples, the Georgians were late as usual – see chart above. God had already distributed all the available land. When asked about their tardiness, the Georgians responded they were busy feasting and toasting in god’s honor, and that’s why they arrived late. Mighty pleased and impressed with the Georgians’ response, god gave to them the only land that he had left: the land he had saved for himself – the best place on earth to plant grapes.

“The digging is done for the season” shares Dr. Mindia Jalabadze, co-director of the Gadachrili Gora Regional Archaeological Project Excavations – aptly shortened to G.R.A.P.E. “The season is only 40 – 45 days due to heat, rain, and student scheduling. All the other time is spent taking measurements, analyzing data, and rebuilding artifacts. Within the next couple years, we hope to have a visitors’ center with a museum and a roof to protect the dig.” The site itself in its current form is unremarkable with most everything covered and protected from the elements until the dig resumes next summer.

“The digging is done for the season” shares Dr. Mindia Jalabadze, co-director of the Gadachrili Gora Regional Archaeological Project Excavations – aptly shortened to G.R.A.P.E. “The season is only 40 – 45 days due to heat, rain, and student scheduling. All the other time is spent taking measurements, analyzing data, and rebuilding artifacts. Within the next couple years, we hope to have a visitors’ center with a museum and a roof to protect the dig.” The site itself in its current form is unremarkable with most everything covered and protected from the elements until the dig resumes next summer.

Dr. Jalabadze walks and talks us through the site. It’s from the Neolithic Age – also known as the New Stone Age – dated to ca. 5,900 BCE - 5,000 BCE. The structures are made from mudbrick with pits and courtyards interspersed – the buildings are thought to have been residences while the pits for storage and/or refuse. He shares that at the time this village was occupied, the climate was much more tropical and wet than it is now, similar to that of the climate in western Georgia, known as it were for being cooler and wetter and as a result often producing wines with more zing and less body.

As the land dried up, the villages were eventually abandoned and left for ruin to be discovered now some millennia later. There are, in fact, several known archaeological sites in the southern Caucasus, many of which have yet to be explored. The current excavation sites were actually known to have existed since the 1960s. There are over a dozen already-known-sites within 100 miles of where the clay pot was discovered that have yet to be fully explored.

The “archeological evidence” is related to an analysis of tartaric acid in the clay pot.

The newly analyzed shards from the clay pot above tested positive for tartaric acid amongst other acids, but the key here is to ensure that the presence of the tartaric acid is, in fact, from what was inside the jar 8,000 years ago and not from current or more modern microbial activity. The acid content is compared to the acid-content of the soil in which the shard was found, and it significantly exceeds the background soil samples. The presence of tartaric acid provides “very strong evidence for the presence of ancient grape/wine in this jar,” according to the U.S. National Academy of the Sciences paper co-authored by Dr. Mindia Jalabadze.

The newly analyzed shards from the clay pot above tested positive for tartaric acid amongst other acids, but the key here is to ensure that the presence of the tartaric acid is, in fact, from what was inside the jar 8,000 years ago and not from current or more modern microbial activity. The acid content is compared to the acid-content of the soil in which the shard was found, and it significantly exceeds the background soil samples. The presence of tartaric acid provides “very strong evidence for the presence of ancient grape/wine in this jar,” according to the U.S. National Academy of the Sciences paper co-authored by Dr. Mindia Jalabadze.

Based on Winkler index values – commonly used for classifying the climate of wine growing regions – the climate in this region from 8,000 years ago is comparable to the current climate of Montalcino. Climatologists determined this by studying timberline data from the mountainous region of Abkhazia on the eastern Black Sea, proxy sediment data from Lake Van in eastern Anatolia, the sedimentary pollen profile of the Nariani wetland, and other data points. The cavemen must have been drinking some primo wine. Too bad we’ll never know what it tasted like.

Finally, we have archaeobotanical evidence which simply put means old botanical evidence: plant remains. Archaeologists have discovered ancient pollen – deduced as ancient because the pollen is present at the Neolithic levels and not the modern top soils. These clusters of pollen are interpretable as the remains of grape flowers along with grape starch found associated with the jar. Based on the archaeobotanical evidence alone, researchers conclude that there were grape vines growing in or very near to the village and that the fruits were consumed by the inhabitants.

We know there was a pot 8,000 years ago with grape-residue and that the residue is as old as the pot and not newly present. We also know that the climate 8,000 years ago supported the development of viticulture, and we’ve found evidence that grapes grew in or near the villages at the time. When stored grape juice readily ferments into wine. If the grapes had been dried as raisins and preserved in the pot, the evidence would have degraded and disappeared from archaeological record – it didn’t. If the grapes were preserved by concentrating them down into a syrup through the application of heat, there would be evidence of carbon splotches – there are none. By process of elimination and the strength of the preceding evidence, we conclude the jars originally contained wine. And like this, Georgia has been declared the Inventor of Wine.

Being the Inventor of Wine is a massive economic and socio-cultural boon. Georgia is hosting more and more international visitors, and its growth in wine exports has been nothing short of rapid – on pace to double by year-end. But, fame and fortune changes people. Can it also change a country and its wine ?

Read part 1 of the series.