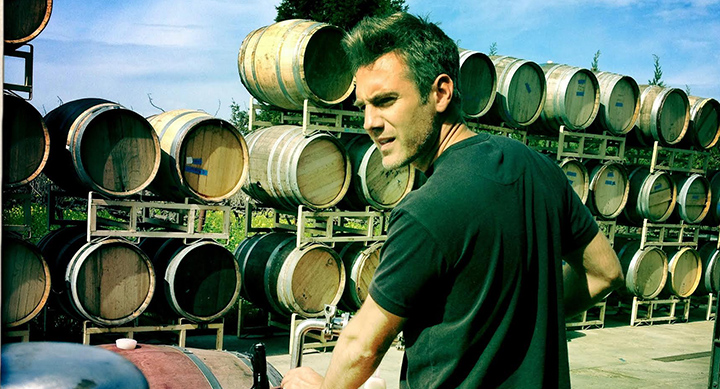

Jack Roberts was educated at Eton College in England (alma mater of 19 Prime Ministers including the current Prime Minister David Cameron), grew up in France and now makes wine in Napa Valley. After working for one of the leading figures in the New California movement, Steve Matthiasson, he started Keep Wines with his wife Johanna Jensen Roberts in 2009. Jensen Roberts has worked with the influencial Abe Schoener of the Scholium Project and Chris Brockway of Broc Cellars.

Roberts' English heritage is referenced via the name of the winery (www.thekeepwines.com) and the image on the bottle. The image is of Beverstone Castle, an 11th century Norman stronghold in Gloucestershire, England. Roberts' father spent his early childhood at Beverstone. It is now mostly a ruin other than the tower seen on the label. It was captured twice during the English civil war and sustained a great deal of damage.

Christopher Barnes: Jack, you're from England, you grew up in France, and now you make wine in Napa Valley. How did that happen?

Jack Roberts: I'm not really sure myself. The short story is that I ended up in Paris working in wine retail and worked in a few places there. It was kind of a sideline for my real gig, which was construction. I was flipping apartments, and then every now and then, between jobs, I would work in wine bars. One that really influenced me at that point was the Le Verre Vole. I was there for four months. It just happened to be the wine bar downstairs from where I lived, so I just turned up one day and asked for a job. They were like, "Sure," and they put me at the station in front of a toaster oven and I was just cooking all day. At the end of the night, we would close up shop and drink a magnum of Morgon or whatever it was from Côte du Py. I was like, "Hang on, this is really tasty stuff."

A few years later, I got the opportunity to go to California and visit a friend who has a vineyard. He very kindly offered me a job there. I was working in the fields with the field laborers. Having grown up on a farm, it was just heaven for me. I was elated to be outside and working in the sun with all these guys who were whooping and shouting and singing songs. That kind of took me into the wine industry. I just went down in the rabbit hole and met my current employer, Steve Matthiasson, who took me under his wing. He's been my mentor ever since, and is really teaching me his love of wine. He's really passed it on to me. So now, here I am. Me and my wife make Keep Wines.

How did you get involved with Steve Matthiasson? He's certainly one of the winemakers that people are talking about. He seems to be in the front of this movement, which is going away from the high alcohol, big California blockbuster wines, and making wines that have a bit more balance, a little bit more complexity.

I wanted to farm, so I applied for an internship with him in the early days of Napa, when I arrived. He gave me a job just going through the fields and taking samples, petiole samples, the kind of stuff that you do during a normal harvest year. It went on from there. We developed a relationship, and got on really well. I just got deeper and deeper into that.

As far as Steve being the low alcohol winemaker, he might take exception to that. He likes to refer to himself as a more restrained winemaker. He's making wines that, actually, Napa always made, if you look back to the 90s and 80s. His style of winemaking is not uncommon. He was drinking that when he was getting interested in wine. He would say he's not doing anything new. This very reactionary movement to the Matthiasson wines is interesting. You could compare him to other winemakers who make higher alcohol wines if you want to, but really, he's just continuing a tradition, I would say.

There is this sort of sense of two camps in the wine world in California. There was a piece in the New York Times a couple weeks ago where they were comparing ...

... The Wrath of Grapes?

Yeah, Robert Parker to Raj Parr. I read something on Reddit that was actually very funny. They compared it to The Life of Brian, where there's the Judean People's Front, and the People's Front of Judea, arguing about the same thing. What is the basic philosophical difference there?

Steve comes from a farming background. Before he was a winemaker, he was a farmer. He worked at various companies in California, and still works as a farmer. He came to winemaking from that perspective. As a farmer, you want to stop for lunch, have your meal, with, perhaps, a glass of wine, and go back to work outside in the hot sun, and not feel like you're going to pass out because of what you've just consumed. He was just trying to do something that agreed with his style of living.

There are two camps. You can't deny it. Some people like to make their wines in a richer style. I occasionally drink those wines, I have no problem with them, I could list several that I love. It's just that Steve happens to want to make a more restrained style of wine. It's amusing, that whole thing. I'm completely following it with great enjoyment.

What have you learned from Steve? What techniques or philosophies do you feel were imparted to you that has taken you in the direction of making your own wines?

Steve Matthiasson, from the beginning, encouraged me to farm on my own, and to make wine on my own. His whole thought process behind that is, since I'm going to be taking care of his wines, I need to understand the risk factor involved, because there is a lot of risk in farming and in winemaking. Unless I'm really thinking, "Did I leave a cap on that? Did I close that valve on the tank?" and triple checking everything, unless I'm in that mode, things could potentiallygo wrong. He likes me to be aware of those dangers, and there's no way of becoming more aware of those dangers than if you make wine yourself, and if you farm yourself. Then you can really understand what is involved. That's number one.

Number two, he encourages me to make wine simply because a rising tide lifts all boats, you know. We're all going to help each other out in the long run. There's no competition or anything of that nature.

It's one thing to be working for somebody, and learning the business; and then it's another thing to take the leap in becoming an entrepreneur in a way, and being responsible for not just the viticulture and the winemaking, but the marketing, the sales, going to tastings, meeting retailers and sommeliers. What was it that drove you to make that decision?

I've got to say, I'm very new to the whole marketing aspect. This is actually my first business trip to New York, and I'm greatly enjoying myself, but this is something I'm newly discovering, and enjoying very much. I had no concept of this whole aspect of the wine industry until four days ago. It's a very new thing.

How did you decide to make the wines that you're making right now?

I love Syrah. Syrah is a great love of mine. My wife and I had the opportunity to lease a small vineyard in Napa Valley called Kahn Vineyard, and that was in 2011. Someone was looking for a young entrepreneurial farmer to take over his little plot, because he couldn't take care of it himself. This man called Bob Kahn, he's a really nice guy. I jumped at the opportunity, and when I heard it was Syrah, I was like, "Oh, even better."

So I got into making Syrah through that vineyard. We make the red and the roséon that little two acre vineyard. It's a tiny venture. It's kind of my weekend away from work, sort of job.

How much wine are you making at the moment?

Our last bottling, we made 350 cases of wine, total. That's rosé, white, and red.

In terms of living in Napa, it must be a big cultural difference for you from England and France. How's it been living in Napa?

That's a really interesting question. You can't tell from my accent, which sounds English, I hope, or expect, but I grew up in France in the middle of nowhere in Gascony, which is traditionally Armagnac country. In the 70s, when my parents first arrived there, it was this wild place, really alive with people and agriculture. It was very vibrant. It's still the place where foie gras comes from, and there are all these things happening there.

During the course of the 80s, there was a great migration from the country to the city. A lot of people left for towns like Toulouse, Biarritz, and Paris, and other places around the world. The youth did not carry on the mantle of farming. It became larger scale farming, and the villages got smaller and more deserted. All that culture was reduced massively. I won't say it completely left, but it was reduced a great degree.

I always missed it. People spoke Patois, and now you don't hear that in the streets anymore. That all disappeared, and so, when I came to Napa, I found this, once again, vibrant community of people who live in the country, and they live and breathe agriculture. They make wine from what they grow, and everybody comes together at harvest, and has these great parties and exchange wines. It's very convivial, it's food, and wine, and it was basically my childhood. When I came to Napa, I was amazed that people like this exist, and places like this still exist in the world.

Napa is an interesting place, because it's a combination of farmers, people that have been making wine there for a long time, and also guys that have sold stock in whatever-dot-com, and made money in real estate, or made money here or there. It's a sort of weird combination of cultures. Have you seen that?

Very much so. Real estate prices are shooting up, people are buying second homes in Napa. This is an ongoing debate, and it's a subject of a lot of anxiety for some people. If you're in the real estate market, then that's great, but if you're a farmer, it's becoming harder and harder to farm your own land, and make your own wine. Having a winery is an almost unattainable dream for a lot of people.

A lot of people now are making wines in places like Oakland, and buying grapes.

Well, that's the thing. It's not just Napa that grows grapes. That's the encouraging thing. You can grow grapes in Sonoma, you can grow grapes in Mendocino. It's just Napa, for some reason, this little sliver of a valley, has become a sort of focal point for everybody to live and enjoy the lifestyle. I think it's good, it's spilling out, and spilling over into other neighborhoods of the North Bay.

Do you have a sense of where you see this venture going in two, three, four, five years time? Or are you just taking it as it comes?

I would say a bit of both. I want to expand our production, obviously that's going to be difficult with a two acre vineyard. I want to continue making affordable, good wines from where I live, for sure, and I want to make more of them.

What are your favorite wines to drink?

I love everything. Napa Cabernet is amazing. I don't find myself drinking it as much as, maybe, other people do, just because it's always there, and so it's kind of always in the background, but I do appreciate it. Syrah, I love to drink Syrah. Nebbiolo, Friuli whites, Friuli wines in general, that Steve Matthiasson introduced me to, I did not know anything about, have become a great love of mine now. Varietals like Refosco and Schioppettino, are completely surprising. I'm discovering new varietals every day that I love to drink. My everyday drinking wine, I would say, I still drink Côte du Py on a regular basis. I love it. A good Beaujolais, never to be sniffed at.

Jack, you make an Albariño. That's kind of interesting.

We source the fruit from a vineyard called the Lost Slough Vineyard, which we discovered through our great friend Abe Schoener, who is the winemaker for Scholium Project. He sources Verdelho, I think, from there, and Gewürztraminer.

My wife, Johanna, used to work for Scholium, and that was how she discovered that vineyard. She was making the wine before I met her, actually, so that's just been a labor of love for the last five years now. It grows in the delta, in Sacramento, near a town called Lodi, more specifically, Clarksburg. You wouldn't be driving past and screech to a halt if you saw the vineyard. It's not a real showstopper, but it's a great location for growing Albariño. It's got the heat, it probably doesn't have the humidity that you would get in Galicia. They don't train the vines the same way. Albariño, I think, works really well in the Lodi area, and so we were really stoked to have that fruit.

We make it in a pretty traditional style, I would say. We ferment it wild, we let it go through malolactic, and then we bottle in the spring. It's crisp, acidic, has an almost salty aspect to it, which I really like. It goes very well with a meal.