Jay Somers started J. Christopher Wines in 1996, with the ambition of making Old World style Pinot Noir in the New World. He follows biodynamic principles and employs an artisanal, non-interventionist approach to winemaking. In 2010 Somers entered into a partnership with famous Riesling producer Ernst Loosen, which enabled him to purchase a 40-acre property on Chehalem Mountain in Newberg, Oregon.

Read Katherine Cole's Grape Collective column on J. Christopher.

Christopher Barnes: You make wine in Oregon and are also represented by Dr. Loosen, which is interesting as you would not expect an Oregon winemaker to be represented by one of the world's most famous Riesling producers.

Jay Somers: Yes. I just like hanging out with Germans really when it comes to it. They're very good at playing soccer.

Are you a soccer player?

Not really. I played soccer, but I would not say I'm a soccer player, so no. I love it. It's fantastic.

Before we talk about the Dr. Loosen relationship, perhaps you could tell us about how you first got involved in the wine business.

Well, it actually goes way back to when my mother was married to this really great guy who sadly passed. I was 18 when he passed. My family really didn't have any wine culture, but my mother married this wonderful guy Darrell Daniels. He was very into wine and in the '80s and '70s, they would go down to Napa and buy wine. To me, the whole concept was just very fascinating. The idea that something was grown, and then made into this product and bottled in small bottles instead of boxes or giant bottles, which is what I'd normally seen wine in. I started tasting wine in my teens. Then later in college, buying wine when I could.

I just became more and more interested in it. Out of college, I got a job immediately making beer for a small company. That was interesting. There's a company called the McMenamins in Portland. The brewing led me to thinking about how if I can make beer, I should be able to make wine. In 1990, I went and bought my first Pinot Noir grapes and started playing around and decided I enjoyed making wine much more than beer. Beer is a lot like baking. It's all about consistency and whatnot. In making wine, you have this whole experience of vintage. It's always different, so that was fascinating.

Then fast-forward to trying to learn about what great wine was. I guess it would have been roughly 1991 or so when Matt Kramer came out with his book Making Sense of Burgundy. I sat in on these classes that he did in Portland, Oregon. I tasted these fantastic wines. Then I made the connection that Burgundy and Pinot Noir in general are what I loved, and that we were growing it 25 minutes from where I was living. It's a natural thing. I got a job for Adelsheim which was great. They hired me for like seven bucks an hour which is amazing, because getting a job in the Willamette Valley in 1992 was nearly impossible as there were like 20 wineries or something.

It was very difficult. I ended up there. I went to Cameron Winery, a great little boutique producer in the Dundee Hills. I worked there with John Paul, who was really my mentor. Great guy, very Burgundy in style vineyard work and also winemaking, long barrel-aging, and natural fermentation. The key thing with working at Cameron is that in the New World, there is a big disconnect between vineyard and winery. You have vineyard guys and you have winery guys. They rarely overlap. Part of my job working with John Paul at Cameron was I had this four acre Clos Electrique vineyard to care for. My whole perspective on winemaking has come from the vineyard which is unusual in the New World.

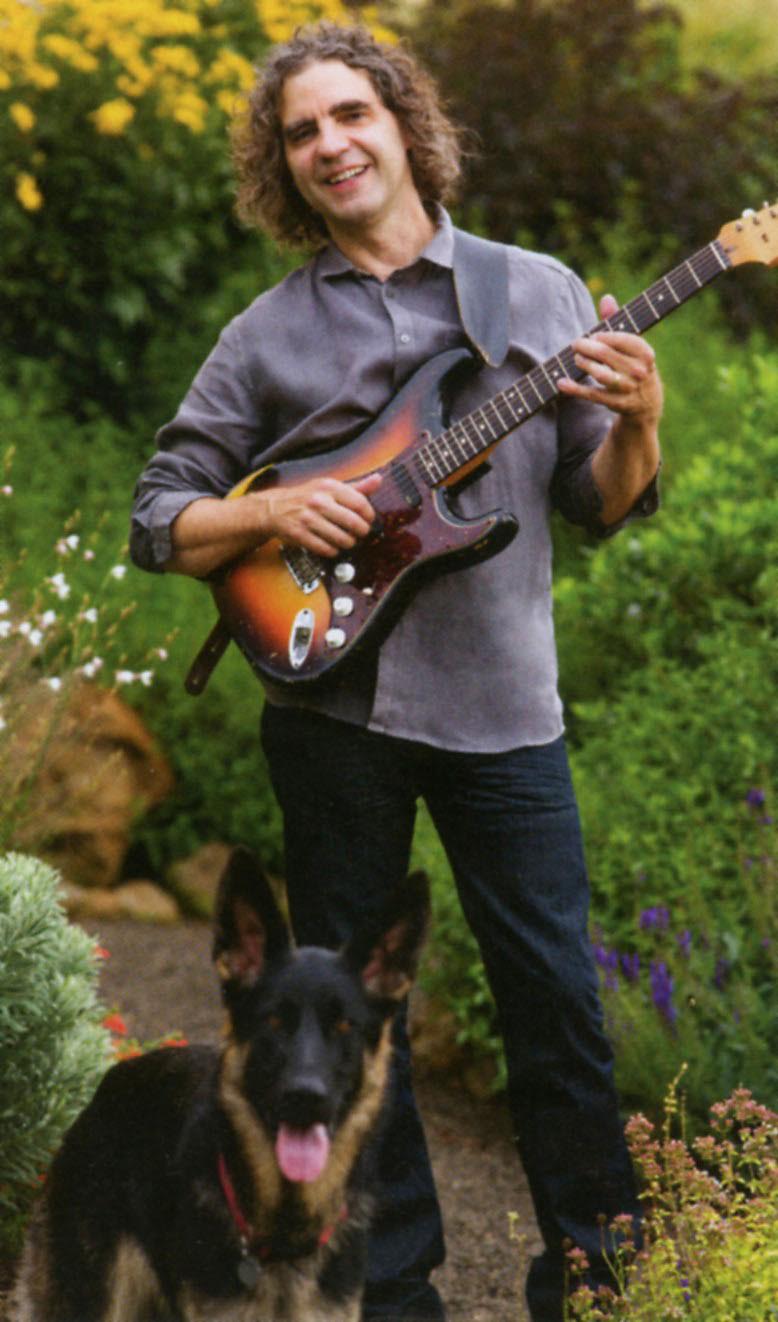

You're also a musician.

Well, I wanted to be a rock star really badly, but that didn't work out. A good friend of mine, Pete Krebs, a musician in Portland, always joked, "I make hundreds of dollars a year playing guitar." That was the reality and so I got into winemaking. I've been a guitarist since I was 15 years old. I collect guitars and plug all things. New York City is actually one of the most dangerous places to visit. I have actually gone home with a guitar the last two times I've been here. I'm a little nervous for my credit cards!

What kind of guitars are you interested in?

I have a lot of different ones, but I really like old vintage guitars if you can find something cool. The problem with vintage guitars right now is the pricing on a lot of the stuff has just gone through the roof. I really like Fenders, old Fenders, the Gibson Hollow Bodies, old Gibson Hollow Bodies, and there are some really great new builders out there now. There's actually a guy down in the Village. This guy Rick Kelly who's making telecasters and stratocaster Fender style guitars out of reclaiming wood from old buildings in the Bowery. I bought a guitar from him a few years ago made of like 150-year-old butternut wood that he salvaged out of the building close by. It's an incredible release, so that's really exciting to me as well.

What is the name of your band?

I have a band called Vin Halen with a couple of winemakers including Tim Malone, who's been working with me at J. Christopher since 2006, and now has his own winery called Timothy Malone Wines. Tyson Crowley plays drums and he has a winery called Crowley, a really great small producer. We have a guy playing saxophone, Jeff Siegel, who imports Austrian wine into the Portland area. The guy is stupidly talented as a saxophone player, and as it turns out, it's not his main instrument. I guess he played violin and mandolin with Joan Baez.

What does Vin Halen play?

We don't know any Van Halen. We play like old soul jazz, so it's Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock stuff, some Stevie Wonder, some original stuff I've written. It's more jazz blues oriented. It's a lot of fun.

My other project is a recording project. It's called Portland Cement. We actually have a Facebook page. We've recorded one album. I have another one that we've been working on for years. I turn 50 in December, so I'm at the point where it's like either I buy a Corvette or I start recording albums, so I'm recording albums. It's like the middle-age crisis thing.

The red Corvette will come soon?

Right. Probably, yeah. I'll get a Corvette.

Tell me about how Oregon has evolved since you started. You said you when you started there were just over 20 wineries.

Over five hundred now.

Oregon is now one of the places people think of when one talks about Pinot Noir.

It is. I've heard that it is the most invested in wine region in the world right now. Jadot just came. Jacques Lardière, one of the greatest all-time winemakers, is now in Oregon making wine which I think is fantastic. Kendall Jackson is there which is a huge winery. They're there and that's great. They do a very different thing. There are all these people coming, but it really started from a small group of small growers. I mean honestly really crazy people. For example when David Lett came up and planted Pinot Noir, and Charles Coury planted Pinot Noir in 1965 up there.

It was a crazy thing to do because it was like oh you can't possibly grow wine in Oregon, it's freezing cold up there. Generally, at that point, the problem with Pinot Noir in American wine growing was that they were trying to grow it in Napa Valley and in St. Helena, where it is much too hot. They don't grow it there anymore. In California, they figured Sonoma Coast, Santa Barbara. They found some very good areas to grow Pinot Noir there, but the Oregon industry slowly evolved starting in roughly the late '60s.

David Lett with Eyrie vineyard, the 75 South Block Reserve won that famous competition in Paris which was shocking. That was the catalyst that put the region on the map. I think it got the attention of a lot of French winemakers. Domaine Drouhin came to the Willamette Valley in 1987. That was really the catalyst that started the whole thing. Slowly more and more people came. The wine started to show very well consistently in the press. We now have 500 plus wineries.

When you did get involved with Dr. Loosen? It must have been really great to have one of the top Riesling producers in the world all of a sudden want to partner with you.

It's great on so many levels. I mean number one, it's another really well-known international winemaker coming to the Willamette and investing because they believe in the region. I met Ernie through Kirk Wille who is the manager director, honcho, and spiritual leader of Loosen brothers USA. A great guy and a very, very good friend of mine. I was invited to a party at Kirk's house once. I knew Ernie was going to be there and I was very nervous. To me it was like meeting Eric Clapton. I told this story 100 million times.

I didn't know it at that time, but Ernie had been buying some of the early wines I was making because I was making them in a very Old World style. He really liked what I was doing. He saw me come in and Kirk said, "Oh, there's this guy." He come straight over to me and he goes, "So you're the Pinot Noir producer." I literally turned around because I thought maybe somebody like David Lett or David Adelsheim was standing behind me or something. He was talking to me, I was so shocked. We ended up drinking Burgundy until three am that night and became very good friends. That was in 2001 I think.

In 2004, we finished the vintage a little bit early in the Willamette. All the wine was in barrel. The white wines were in a very good place. Just finishing fermentations. I was in my basement office at my house in Portland going through the giant pile of mail and the emails and everything. The phone rings and it's Kirk. He's in Germany. He's like, "Hey, we were having a problem. One of our interns over here didn't show up and everyone else has to leave and the vintage is going much later in Germany."

It was the easiest wine gig I had in a long time. I went over there and helped them finish for the last three weeks of harvest. Over that time, Ernie and I would sit at night and drink wine after I was done working. We started talking about making Pinot Noir in the Willamette. That took five years and hundreds of thousands of dollars for lawyers and accountants, but we finally got a nice agreement worked out. The initial idea was really to start a brand new winery, but we found out very quickly that trying to source really great older vineyards was nearly impossible, as it is still is today. It's really hard to get a great old vineyard.

We decided the best thing to do was to have Ernie just invest in what I already had. Basically he's come in with a lot of capital investment. We have replanted vineyards, built a beautiful state of the art winery, underground barrel caves, a really efficient winery. We're completely off the grid power-wise. In fact, the power company owes us money but I just don't know how to get it back from them. I can't figure that out. Really, one of the great things about having Ernie as a business partner is that he's a very fun guy which is fantastic. At the same time, he's a very good businessperson and understands the wine business maybe better than anybody.

Having someone like that invest in a winery, he understands the nature of wine and the nature of vintage. It's never been about making his investment back immediately. He understands what we need to do in each vintage as far as the mix of wines because the wine will tell you where it needs to go. You can't state, for example, we're going to have 3000 cases of $70 wine this year because we need to make X number of dollars. If you don't have the quality and the bottle, it's a terrible plan. An investor that's just looking for money back will force you to do that, which is why I think a lot of New World wineries have had some difficulties getting going.

You mentioned it was the mutual love of Burgundy that brought you guys together.

Exactly.

Can you talk about the type of wine you make as it relates to Burgundy? I mean clearly they're very different from many California or Oregon wines that one would taste.

Well, first and foremost, our terroir is distinctively Willamette Valley. We can't change our dirt and our climate. We're always going to have the Willamette Valley as a mark. The thing that makes what I do a little different, and I'm not the only producer in the New World like this, is that we make wine using all the concepts and techniques of the Old World. It's natural fermentations, very long elevage time in barrel or 20 months in barrels, and most importantly we don't inoculate for the secondary fermentation.

It's very typical in the New World to add the malolactic yeast culture almost immediately, so that your secondary malolactic fermentation goes very, very quickly. You end up with this really fruity wine which is not a bad thing. It's just a style. It's a different style. In a perfect world, like say with the 2011 vintage, malolactics finished the following September. It's been ten months on the lees of going very slowly through this process, so that the wines develop these really fantastic, earth-driven aromatics and more texture.

It's really a difference of how you approach just the fundamental aspects of making wine. If you're forcing the wine to go where you want it to, or adding enzymes. I get a book from various wine supply companies. It's full of all these powders and liquids you can add to the wine. I honestly don't know what any of them do which is really good because we try to do it as naturally as possible.

Are you organic or biodynamic?

We're not certified either. Our estate vineyard, the Appassionata Vineyard, has been farmed organically from day one. We've never sprayed an ounce of herbicide and rarely do people use pesticides. You use pesticides and you cause more problems than you've solved because then you go out there and you kill everything. It's a terrible thing. Then we started the vineyard using biodynamic principles, which is different than being a biodynamic producer, because to be technically biodynamic, you need to be certified by the Demeter thing.

My personal opinion on that, and this is just how my brain works, is I feel like these people have taken this intellectual knowledge and brought it to this thing that they now own and control. Honestly, I think when Steiner came up with some of these concepts, the wine industry took a little bit of it and went out and made a religion out of it. It's like Scientology or something like that. Those are very positive aspects of it. I think to follow their concepts and be certified and get the gold star on the forehead and pay them a bunch of money, I just don't see it as being necessary when you can just look at using some of these ideas to achieve certain things, like a really healthy soil.

The best part of biodynamic farming, at least in my perspective, is that you look at your vineyard or your farm as an ecosystem. For that to be possible, you need to have some animals. We have our coyotes and bobcats. The deer we keep out, but they are in the area, birds and all sorts of bees. We have bees. We have all these native plants. We didn't take all the trees out. We have trees in the middle of vineyard blocks. We have this very natural situation. I think if you do that, you'll have a much healthier farm because really what you want are these beneficial insects.

If you just clear cut everything, then you have nothing else. Then you have this monoculture that makes it very difficult for all this stuff to survive. And very importantly, we also do not irrigate. Irrigation with any of the vineyards we work with is not allowed, it is completely forbidden. One, it's an ecological disaster in my area because these guys are pumping the aquifer dry. We do not have a lot of groundwater. For example, Patricia Green and Beaux Frères, some good friends of mine at Ribbon Ridge, they have to truck water in during harvest because their wells can't keep up in the summer.

I think it's a very poor use of water to be controlling the growth of vineyards, or getting your vineyard to full production in three years as opposed to six or seven years. Then more importantly for the wine, the vines wants water, right? They will find water. The only way to find water is down. We're trying to encourage this deep root system. My feeling is that the deeper your roots go, the more interesting layers of soil they're going to access. If you actually believe in the concept of terroir, then it's very important for the root systems to be deep.

Going back to Burgundy, tell us what it is about Burgundy that really inspired you to produce wines in the style that you do?

That's a very difficult question actually. Burgundy is a minefield as well. I mean there's great Burgundy, and there's Burgundy that's not so great, and I've had everything. When you get good Burgundy or superior Burgundy, I think it's unlike anything on the planet. It's so balanced. It's so nuanced. It is typically lower alcohol which I think is great, and great acidity. There's just something metaphysical about it. I think everyone has these experiences whether you're into beer or Burgundy or fly fishing or surfing or whatever.

Everyone has something that grabs them. Burgundy was that for me. When I started making wine, it just made sense to me. It was very easy to transition from not making wine to learning a little bit and making wines that were good. I think one of the biggest things that people don't study before they become winemakers is the great wines of the world. They don't actually understand what the great wine taste like.

For me, it is important to understand what great Burgundy is, and what it tastes like, not that you have to buy Romanée-Conti and have a vertical tasting of like impossibly expensive wines. There are wines you can try. There are tastings you can go to. You can educate yourself very easily. If you don't know what the wines taste like, how in the world are you going to possibly blend a wine in the proper direction? It's impossible. You see a lot of confused wine out there that is more recognizable just as red wine, as opposed to a wine that comes from a place.

Burgundy is very much about the terroir of Burgundy. You're making wine in a similar way but in Oregon, and specifically in Dundee Hills. Tell us about the specificity of the areas that you are making your wines.

For me, Burgundy is the holy land. That's where Pinot Noir comes from. With our industry, when I look at what I'm doing with Pinot Noir, I always look back at Burgundies and think, okay what do these guys do? Not that everything translates 100% because they are very different places. What's really interesting about Burgundy is as you go from village to village, the terroir changes dramatically. You go from Marsannay all the way down to Volnay. You have really different wines. As you go down headed south, it changes for each village. To me, this is fascinating.

I mean it happens with most grapes, but Pinot Noir like Riesling is particularly transparent to where it's grown. In our region, the main thing to talk about is Oregon Pinot Noir which is great. People know that it comes from Oregon, but I feel like we won the Oregon battle in the '90s. People know about Oregon Pinot Noir, and now it's really time to talk about a more specific place where it comes from. Really Pinot Noir, the high quality Pinot Noir in Oregon, is grown in the Willamette Valley, which is a pretty big area. I look at the Willamette Valley kind of like you would look at Burgundy as a region.

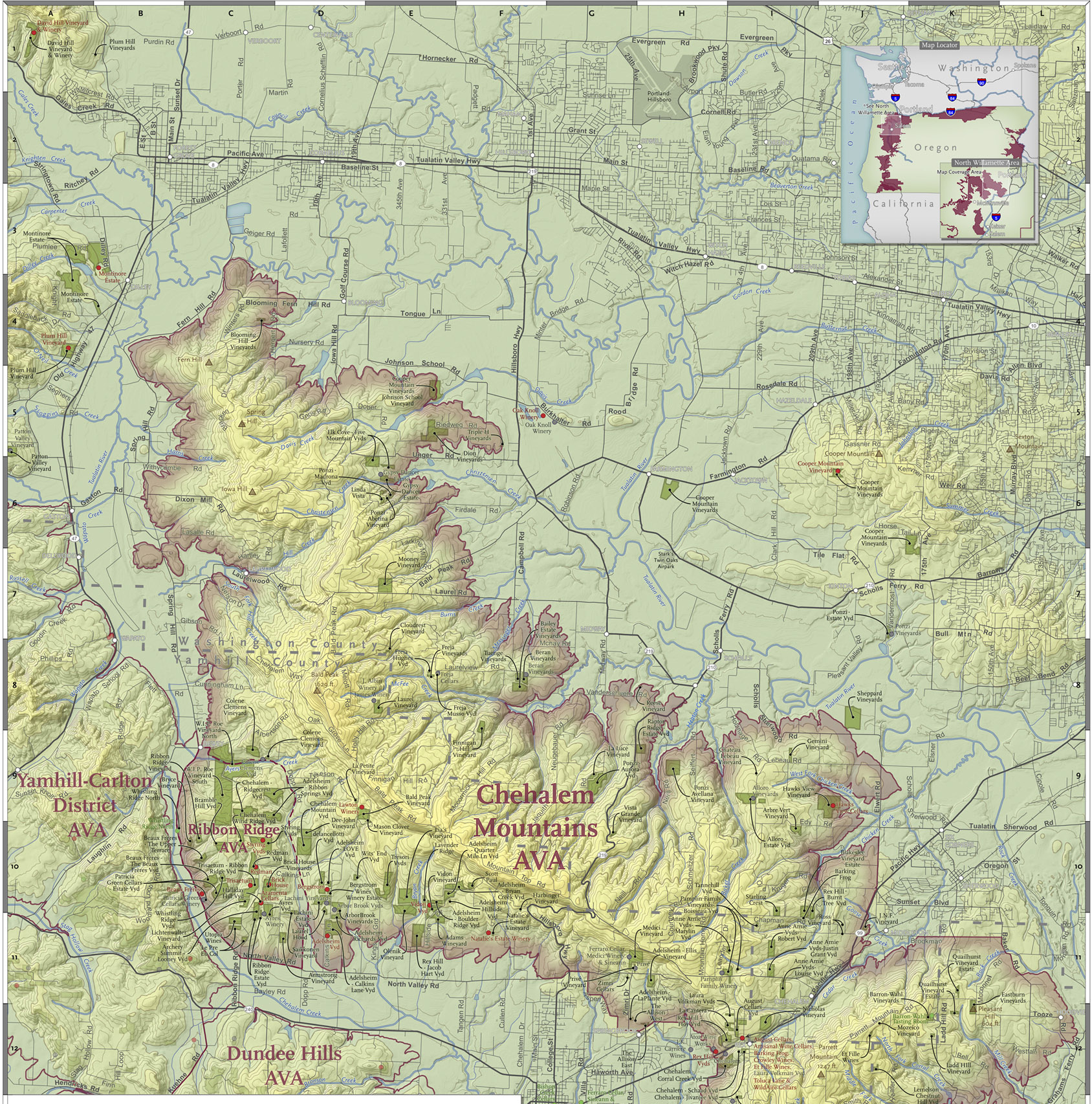

Then in Burgundy, you have the villages, Volnays, Morey Saint-Denis, Chambolle-Musigny, whatnot. In our region in the Willamette Valley, we have AVAs or American viticultural areas. We have Chehalem Mountain where we're located. Ribbon Ridge off to the side. Dundee Hills, Yamhill-Carlton, McMinnville foothills, and to the south Eola-Amity Hills. As we go from AVA to AVA, not only do the soils change, but obviously the microclimates change and therefore the terroir is quite different.

We just tasted a couple of different wines from 2 AVAs and they're really different, yet I can drive from our winery in Chehalem Mountai and in 10 minutes, I'm in Dundee, yet we have radically different wines. Like I've said a couple of times already, what's really great is to be able to make these wines that show this great sense of place of where they come from, their terroir. I would say trying to describe terroir is like seeing a UFO and then trying to describe it to someone, because I was like, "What? Did you just say you were Big Foot?"