Legendary vintner Nicolàs Catena Zapata is credited with revolutionizing the perception of Argentine wine by being amongst the first in his country to produce premium brands. Since 2009, his daughter, Laura Catena, has been traveling the world, with boundless enthusiasm, to tell the story of Argentina’s signature Malbec wines.

Laura, a U.S.-trained physician, commutes between Mendoza, where she serves as Managing Director of her family’s iconic Argentine winery, and San Francisco, where she lives with her husband and three children and practices medicine as an ER doctor. Her interest in science led her to found the Catena Institute of Wine (CIW), a research facility in Mendoza, whose vision is to uncover the country’s true winemaking potential.

Recently, Laura took time from her hectic schedule to visit Grape Collective and talk about her hope that Argentine wine, in her words, “can compete with the greatest wines in the world.”

Lisa Denning: Like many Italians, your great-grandfather emigrated from Italy to Argentina back in the late 1800s and planted his first vines in 1902. Can you tell us the history of the winery since that time?

Laura Catena: My grandfather, Nicola Catena came from Italy where they had vineyards at his house and they made wine at home. He had the idea that he wanted to have a winery and sell wine. He had heard that in Mendoza there was land and good wines could be made. He came to Argentina, and first worked a little bit, then moved to Mendoza and planted some vines in 1902 in the Eastern part of Mendoza. He just started working, him and his wife, Anna. They were the only two employees, planting the vineyards, making wine. There were so many immigrants coming. Six million Italian and Spanish immigrants came during this time. There were a lot of people to be fed and drunk. They needed their wine for their meals because they were used to it in Europe and so there was a very strong business.

Laura Catena: My grandfather, Nicola Catena came from Italy where they had vineyards at his house and they made wine at home. He had the idea that he wanted to have a winery and sell wine. He had heard that in Mendoza there was land and good wines could be made. He came to Argentina, and first worked a little bit, then moved to Mendoza and planted some vines in 1902 in the Eastern part of Mendoza. He just started working, him and his wife, Anna. They were the only two employees, planting the vineyards, making wine. There were so many immigrants coming. Six million Italian and Spanish immigrants came during this time. There were a lot of people to be fed and drunk. They needed their wine for their meals because they were used to it in Europe and so there was a very strong business.

(Laura Catena with her father Nicolàs Catena Zapata)

He was mostly making the wine and the wine would be taken to Buenos Aires in barriques on the train and they would be sold in Buenos Aires. He was not bottling his own wine. Then my grandfather, his son, started selling a lot of wine in Buenos Aires. He was a very good blender. He used to have a blend called Tinto Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. It was the prestige blend that was sold in all the restaurants.

Then my father came around and he said, "Wait a second. Why are we letting somebody else sell our wine and bottle it? We should be bottling our own wine." My father, in the '60s, started bottling his own wine. That's how the real Catena bottled wine was born in Argentina. Argentina, at that time, the '60s and '70s, was the fourth largest producer of wine in the world. The fourth or the fifth. I don't remember. Also, the per capita consumption in Argentina was as high as in Paris and Madrid and Rome and all the European capitals because we had these European immigrants that were drinking the wine. In Argentina, we drink wine with lunch and dinner. When I was a child, that's what you had. You had water and you had wine. Lunch and dinner. My father started bottling his own wine, selling the wine in Argentina. He became very successful with some special blends of Malbec and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Then, in the 1980s, there was a military government in Argentina. My father decided it was quite dangerous. It was. I was a teenager then. There would be people with guns. My uncle was kidnapped. My father had to negotiate the ransom. My father decided to go to California as a visiting scholar. He was invited at U.C. Berkeley. There, in California, he would go to Napa.

Did the whole family go with your father?

Yes, my father and mother, my brother, and myself. My little sister, Adrianna, there's a famous vineyard named after her, she was born in Berkeley. My father would go to California, to Napa, and all of a sudden he said, "Hey, these guys think they can compete with the French." He heard about the judgment of Paris. He said, "If they can do this in California, why not me in Argentina?" He went back to Argentina and basically started working on the soil, the climate. He found these high altitude regions where there were no vineyards, but where you could make this very concentrated wine with moderate alcohols, nice acidity, age worthy wines. A place like Gualtallary, where the Adrianna vineyard is planted in 1992. There were no vineyards there before.

He also brought all the technology because most of the wines in Argentina were made in the old Italian oxidized style, which was these gigantic barrels that were used for 50 years where lots of oxygen would be coming in. The wines were smooth with pretty high volatile acidity. Not bad, but they all tasted the same. My father realized that in order to make these wines of terroir, he had to have the right press that would be very gentle on the grapes. He brought this rather basic technology in Europe, which was not being used in Argentina. When you put all this together, he started making these incredible wines in the '90s that he started exporting.

Was there a point where he sold the winery?

No. In the '80s, he sold some of his table wine brands, but he never sold the winery. We actually had two family wineries. One that was making the high-end wines, and one that was making the table wines. He basically kept the winery making high-end wines and then sold some of the table wine brands.

I had read that he had sold part of the winery to his brothers and then he was able to get it back because they defaulted on the winery.

It is true. In the Italian family, just like in all other families, the parent hands down things to the siblings. His great-grandfather, Nicola, the founder, left the winery and a vineyard to each son. My grandfather ended up having to support his siblings. They all went broke except for him. Argentina is a hard place to do business. We had 1000% inflation. Imagine that. Every day you're changing the price tag.

It is true. In the Italian family, just like in all other families, the parent hands down things to the siblings. His great-grandfather, Nicola, the founder, left the winery and a vineyard to each son. My grandfather ended up having to support his siblings. They all went broke except for him. Argentina is a hard place to do business. We had 1000% inflation. Imagine that. Every day you're changing the price tag.

My father and his siblings consolidated what was owned by my grandfather. My father did buy out one of his siblings. There was some family buy in/buy out sort of situation. He did sell some of the table wine brands, but he didn't actually sell the winery, no, or the vineyards. The interesting thing is my great grandfather, he left the winery and a vineyard to his three sons. Do you know what he left to each of his daughters? A husband and he was very proud of that.

A husband. How did he manage that?

If you asked him, "What did you do for your children?" He said, "I left a winery and a vineyard to my sons and I found a husband for each one of my daughters." I said to my dad, "Listen, I found my own husband. I want a winery and a vineyard." He said, "That seems fair."

That's funny.

Those were other times, right? My great grandfather would be shocked to see me here today. He would be shocked to know that we're selling Catena wines all over the world, in the US, in Italy, in China.

One of your first consulting winemakers was Paul Hobbs.

That's right.

Paul Hobbs convinced your father that Malbec was going to be the grape for Argentina. Can you tell us the story of how that all went down?

You've obviously heard Paul Hobbs' version of this. Basically, there were many consultants coming down to Argentina. There was Jacques Lurton. There was Paul Hobbs. There was Attilio Pagli. There was Alberto Antonini. When people came to Argentina, the first person they saw was my dad because they wanted to know from him, "What should we do?" My dad had this great deal that he would propose to people. He would say, "You make your wine at our winery and then I charge a low price, but then you teach my team everything you know."

Paul Hobbs came down and Paul Hobbs was a consultant. Attilio Pagli too, the Altos Las Hormigas, the first couple of vintages, were made at our winery. All these people, Jacques Lurton was the Cabernet guy. He taught my dad a lot about Cabernet. My dad, at the beginning, was more convinced about Chardonnay and Cabernet. Paul was incredible with Chardonnay. He knew Chardonnay. He still knows Chardonnay. I love his Chardonnay. He basically told my team that if you let the Chardonnay get oxidized it's no good. He taught the Argentina team how to make a Chardonnay more in the French style.

For Cabernet, I feel like Jacques Lurton from Bordeaux was a bigger influence than Paul. My dad basically told his team, "Guys, show me that Malbec can do what Cabernet and Chardonnay can do in Argentina. Show me that the French were wrong when they kicked it out of Bordeaux." You know, in the 19th century, Malbec was more widely planted in the Medoc than Cabernet Sauvignon. It was the primary grape. When it came to Argentina, it came as the king of kings. It wasn't Cabernet, it was Malbec. In Argentina, all the vineyards were overcropped. High production. The quality was not so good for the Malbec that was there. My dad gave this challenge. Honestly, Paul was not a big believer in Malbec and that's why the first couple of years, he said, "Chardonnay and Cabernet." We made 1990, '91, '92, '93, '94, '95 Cabernet. '96 was Malbec.

That was the first Malbec you made?

Actually, the Catena Malbec was '94. The Catena Alta Malbec was '96. The real person that changed the history of Malbec for us was Attilio Pagli who had worked at Antinori. When he came to our winery he was part of the Alto Las Hormigas project. My father said to him, "You guys work with Sangiovese in Italy. It's your own different variety. Which is the variety that you will put your bet on for Argentina? Is it Bonarda? Is it Malbec? Is it Cabernet Sauvignon? Is it Chardonnay?” Attilio said, "Give me a couple of weeks.” And then he tasted through all our vineyards. He came back and he said, "I can tell you one thing for sure. You will never make a great Sangiovese, but I think your Malbec is very special." He fell in love with the lot 18 of the Angelica Vineyard. The vineyard planted in the 1930s. In the '90s, it would have been 60-something years old. He said, "This is gold."

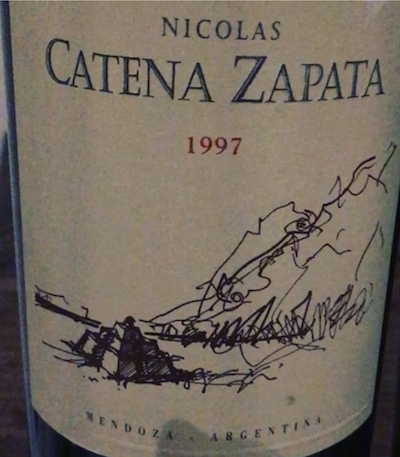

The first Malbec we made was based on Attilio's advice. Then, actually, Paul got excited by it. Then, everybody was excited by it, especially with the '94. We did quite well. Parker gave it a good rating. Actually the first article in a major newspaper was in the Wall Street Journal. Dottie and John wrote that article. The 1997 Catena Malbec was in the newspaper as the number one wine, the number one Malbec from Argentina. It was the first that people knew about Malbec. After that article, it was a lot easier to sell Malbec. Up until then, I was still in medical school. I had my life as a doctor. I would go once in a while to sell Malbec. I would go out and many people would love the wine, but they'd say, "I can't sell it. Nobody knows Malbec." After that article, which I believe was either 1999 or 2000, everything changed. People knew Malbec all of a sudden. It had a big impact. People have a hard time believing that 20 years ago nobody knew what Malbec was.

The first Malbec we made was based on Attilio's advice. Then, actually, Paul got excited by it. Then, everybody was excited by it, especially with the '94. We did quite well. Parker gave it a good rating. Actually the first article in a major newspaper was in the Wall Street Journal. Dottie and John wrote that article. The 1997 Catena Malbec was in the newspaper as the number one wine, the number one Malbec from Argentina. It was the first that people knew about Malbec. After that article, it was a lot easier to sell Malbec. Up until then, I was still in medical school. I had my life as a doctor. I would go once in a while to sell Malbec. I would go out and many people would love the wine, but they'd say, "I can't sell it. Nobody knows Malbec." After that article, which I believe was either 1999 or 2000, everything changed. People knew Malbec all of a sudden. It had a big impact. People have a hard time believing that 20 years ago nobody knew what Malbec was.

It's so popular now. It's on every wine list.

What's important to me is that it's not a fashion. This variety existed for 2,000 years, since Roman times. It's in the Encyclopedia Britannica from 1879. It says Malbec is the most widely planted variety in the Medoc. It comes to Argentina. It's lost in France because it was a late ripener and it was susceptible to frost. They were tired of weather problems. Cabernet is a lot tougher. Merlot ripens earlier. They said, "You know what, this Malbec is too complicated for us. We like it. It makes great wine. It softens the Cabernet tannins, but Merlot is less complicated and we can harvest it earlier. We're not going to replant it." Then, it gets saved in Argentina. But, it almost didn't get saved in Argentina. Honestly, until Attilio Pagli came and told my father this, most people did not believe in Malbec. They believed more in other varieties.

You're a fourth generation winemaker. Your father has turned over the daily operations to you. You're also a practicing ER doctor, a mother, and you split your time between San Francisco and Mendoza. How do you juggle all that?

It is quite complex and not simple, especially with a husband and three children. That might be the most complicated, except I have very self sufficient children, thanks to this.

How old are your children?

They are 21, 18 and 14. I believe that the way to do many things is by really prioritizing and knowing what you need to get an A+ on and what you can get a B or a C on. As a physician, I work only four to six shifts a month. It's a very part-time job, but I know I have to be a great doctor every day. I don't do any wine events or drink the night before I'm working. I don't fly an overnight when I'm working. I'm 100% focused on the hospital. When I'm making wine at the winery, when I'm talking to my team, when I'm traveling for wine, I'm giving that my 100% too. My husband is very present when I’m traveling and there at home with the kids, so that’s very helpful. He is also a doctor. I don't think I could do it without him. I have a very good babysitter too. Really, it's about prioritizing.

The one thing is that medicine and wine actually share a lot of things in common. There is the scientific aspect. There is the art. A great doctor is somebody who has a good gut instinct about a patient just as much as the scientific background. In wine, there's a lot of instinct about when you're making a blend, about your palate. The art/science combination is quite strong in both disciplines. Both require you to be very focused. You need to plan ahead. You need to be able to deal with uncertainty, which is found in health. You never know what disease somebody is going to have. In viticulture, you don't what the weather is going to bring you. Actually they're two professions that I feel have helped me, one the other.

And, at this point, are any of your three children thinking they will go into the family business?

My middle son, Dante, works at the winery. In the summers and the springs, he always likes to go with me. He likes to be at the winery with the barrels and do the basic work of the winery. He really enjoys the manual labor part of making wine, which I do too. It's really quite fun. He has quite a good palate too. In Argentina, he's 18, so he's allowed to drink a little bit. I do believe that children should not drink. It is true that alcohol is toxic to the brain. It's really developing until age 23 or 25. My oldest son wants to get a PhD in chemistry and build molecules, so I'm not sure. And my daughter's 14. She actually wants to be a politician. So we'll see.

My middle son, Dante, works at the winery. In the summers and the springs, he always likes to go with me. He likes to be at the winery with the barrels and do the basic work of the winery. He really enjoys the manual labor part of making wine, which I do too. It's really quite fun. He has quite a good palate too. In Argentina, he's 18, so he's allowed to drink a little bit. I do believe that children should not drink. It is true that alcohol is toxic to the brain. It's really developing until age 23 or 25. My oldest son wants to get a PhD in chemistry and build molecules, so I'm not sure. And my daughter's 14. She actually wants to be a politician. So we'll see.

When you decided you wanted to become a doctor and you started studying, there was a point where your dad had a grand scheme to get you into the wine business because he wanted you to work with him. What was this scheme of his?

I didn't realize this until later, but I was set on medicine. I wanted to help people. To me, I would not help people with wine. I've changed my mind about that. I think that what my father has done for Argentina, which was to create an export business. Exporting gives you a lot more stability as a region because you have two different places, two different currencies. Also, it's kind of exciting that your wine is drunk by other people in other countries. It gives you energy to work harder, to make better wines. This revolution that my father started in the 1980s has changed so many lives. I genuinely think that making wine you change lives because it's all the people who live from this and all the people in the countryside who depend on wine for their livelihoods and their children's livelihoods.

Going back to your question of how my father got me into this, we used to go to France together when I was in college, in medical school. I almost minored in French. I took a lot of French classes. I’ve been speaking French since I was quite young. Not because I wanted to do something with wine. Mostly because I liked French Literature, like Camus and Sartre who were my heroes. My father asked me to go as his translator to France when he was going to taste the Grand Crus in Burgundy. He was on this exploratory trip where he wanted to figure out how these people make such incredible wines that are so beautiful and age-worthy. You know, kind of like the famous Harlan-Mondavi trip that they took to Europe. That whole story is in my book, Golden Vineyards, that I will give you a copy later. It's actually coming out in the next few months. It's about the most iconic wines in the world. It actually has the story of when Bill Harlan and Rob Mondavi went to Bordeaux. That's when their little light bulbs switched on.

It was one of these sort of things that my father took me to France to taste and I was his translator, yet I was soaking in all this history and all this energy and all this knowledge. My obsession with old vines comes from there. I think that my father was thinking, okay, if I go on all these trips with her, maybe she will fall in love with wine. That's exactly what happened.

At that time period, were you already working as a doctor or were you still a student?

I was doing my residency for part of the time. When you're doing your residency, you're actually getting paid. Not a lot, but you're a doctor. After medical school — medical school is 4 years — I finished in 1992, and then you do your first year of residency, your internship. After that, you're an official doctor. You can sign prescriptions. It was during that time. And a little before as well. On all these trips, I was not thinking I'm going to work with dad. I was thinking I'm going to spend my life drinking the family's wine and practicing as a doctor!

Getting back to Malbec. There seems to be two styles, the bigger, fruitier style and then what they now call the modern style that's leaner, with the grapes coming from higher altitudes. Which direction do you see Malbec going in Argentina? What's your style?

I think I would not talk about two specific styles. Although I see where you're coming from because I do think that when Argentina started exporting there was this great temptation to use a lot of oak to have wines that were very ripe. I think that's what people were doing in California back then also, if you think about the '80s, early '90s. Argentina was kind of following along. That was more of a winemaking style.

I think I would not talk about two specific styles. Although I see where you're coming from because I do think that when Argentina started exporting there was this great temptation to use a lot of oak to have wines that were very ripe. I think that's what people were doing in California back then also, if you think about the '80s, early '90s. Argentina was kind of following along. That was more of a winemaking style.

I think more about a terroir style in the sense that, to me, each terroir has a winemaking way that best enhances that particular flavor. I think more of region-based styles than of two styles, let's say one riper and one more refreshing and mineral. In terms of the regions, you have Salta and Patagonia, two completely different areas from Mendoza because Salta wines have more herbal notes. It's like a different planet. You have Patagonia that doesn't have altitude. You have more of the wind influence, big night/day differentials. Those wines are also very different. Then you have Mendoza where you have 25 different districts, or appellations. They all have different tastes. We actually did a study with UC Davis where we compared the flavor of Malbec aromatics and palate and we did it chemically and by sensory analytics. By the end of all the data, I could actually give them a bottle of wine without telling them where it's from and they could test it and tell me this comes from Altamira. This comes from Monterrey, California. Because they have such distinctive flavor.

To me, the real distinctive flavors are for each region in Mendoza. However, I don't think Argentina's done a good enough job telling people about these distinctive flavors. I think that people don't really know what this Altamira tastes like, for example, the way they know what Pomerol and Pauillac tastes like or Meursault and Givrey Chambertin. I think that we have those distinctive flavors, and we need to taste and taste and taste so people get to see them.

Now, in terms of a richer or less rich style, I think some winemakers like a riper style in Argentina. Some like maybe a little earlier harvest. What we like to do is if we have a particular vineyard, we will study the soil. We have a vineyard divided into hundreds of parcels. Each parcel is treated differently with a different pruning method, a different cover crop, with the idea that there is something distinctive about that place. We have studied them and they do have different flavors. For each place, we will harvest it at a distinctive time. Let's say that there's a place where we love the violets. The violets are only there between fifth of March to fifteenth of March. If you go too ripe, you're going to lose the violets. If you go too early, you're going to get some green flavors. That's when we're harvesting that and we're really maximizing the violets. Let's say another location has something about the texture of the tannins. Maybe that happens a little later. We might harvest that a little later.

The way I think of winemaking is I want each parcel to have its character maximized in terms of viticulture. Then when you make the wine, you have to decide to keep that separate. We have the Adrianna parcel wines, which are 1.5-hectare bottled. Boom. Every vintage will be different but there will be kind of a guiding line. Then we do some blends which are selected parcels that go together every year and that has more of a, I call it a Chanel No. 5 effect, which is the best of all worlds because you get a little minerality and you get a little red fruit and a little violet and a little texture. You put all that together and you get the perfect wine with the perfect balance, although perfection is not always what you want. Then you have the single parcel wines.

In answer to your question, I don't think there is a single style. I think that each place has a particular flavor. The winemaker and the viticulturist can decide whether to make the wine in the riper style or the leaner style. I would say for us, we live in both worlds because I have some wines that are big and kind of beefy and it's old vines and we let them be a little ripe. The alcohol is 13.5. I don't like high alcohol ever, but it's a little beefier and it's got a nice bit of oak. It feels powerful. Then we have the Adrianna Fortuna Terrae, which is almost like a Pinot Noir because it's so floral and it's so delicate. The tannins are so smooth and light. To me, these two parcels that go into this, lend itself to this. The other one lends itself to that.

Can you tell me about the Adrianna vineyard in the Uco Valley?

Adrianna is in the Uco Valley in Gualtallary. Mendoza is the province — comparable to California, for example. Then Uco Valley, Lujan de Cuyo, and Eastern Mendoza which are the bigger regions. Uco Valley would be like, let's say, Napa. Inside Napa you have Rutherford, for example. Well, Gualtallary is inside Uco Valley. Altamira is inside Uco Valley. Altamira and Gualtallary are very far apart. They're a 45 minute drive. Very different terroirs. One is south, so that makes it cooler because it is south but it haslower altitude. The other is higher altitude and west.

There are totally different soils, too. As you get closer to the mountains, you get the bigger stones. A lot of calcareous, with really good drainage. As you go further down, you get more clay. Really, you have so many different terroirs in Mendoza. This is something that the world does not yet know. That we can find these really different flavors. That's why I think it's so exciting, where Argentina is right now, because we have everything to tell the world about our region.

The Adrianna vineyards are almost at 5,000 feet altitude. Isn't that almost verging on being too high to grow grapes?

The interesting thing is when my father planted there in 1992, he was told by his own viticulturist that a red variety, especially a Bordeaux variety would never ripen there, and that we’d be lucky if Chardonnay ripens there. But my dad thought, "Hey, we have more sunlight. Even if it's cool like Burgundy, there's enough sunlight. We have a little bit of the stones on the surface, which gives a little warmth too, and we don't usually get the late summer rains like they get in France. We do get cooling of the weather, but it happens really gradually. Although we have rains in the summer, they usually stop towards the end of it.

The interesting thing is when my father planted there in 1992, he was told by his own viticulturist that a red variety, especially a Bordeaux variety would never ripen there, and that we’d be lucky if Chardonnay ripens there. But my dad thought, "Hey, we have more sunlight. Even if it's cool like Burgundy, there's enough sunlight. We have a little bit of the stones on the surface, which gives a little warmth too, and we don't usually get the late summer rains like they get in France. We do get cooling of the weather, but it happens really gradually. Although we have rains in the summer, they usually stop towards the end of it.

My father thought we would have a longer season and maybe we’d be able to ripen these Bordeaux varieties, like Malbec, with nice, not too high alcohol, good flavors, good evolution of the tannins. He bet on this and he was right. He got lucky. He always says, "I just got lucky." Basically, it seems like it would be at the limit of wine cultivation but it’s not. We achieve ripeness pretty much every year. In 2016, which was very cool, we made incredible wines — floral, beautiful, and definitely not underripe. There's something about that place, that even if it's very cool, you can achieve ripeness every year.

Do you feel Argentina is too reliant on Malbec and should branch out? What other varieties do you think could become as well-known as Malbec for Argentina?

I think that Malbec is a very historic variety that almost went extinct, that was reborn in Argentina. Why has Malbec been so important in the world? Because it tastes good. It's got beautiful aromatics. It's got those smooth tannins. It's got complexity. It can acquire different tastes in a different place, sort of like Pinot Noir does. In each soil and climate it has a different aromatic profile and flavor. To me, Malbec has so much more to give than what's being given by it now or what people perceive it as. You wouldn't ask somebody in Burgundy, "Hey, don't you think you should try a different variety?”

There's so much diversity, so much beauty. To me, we've just started to see the beauty of Malbec in Argentina. There's so much more. I would hate to say, "Oh, we need some sort of new thing." On the other hand, because we have 2,000 miles between the north and the south of Argentina where wine is made, and we have these soils that are completely different, whether they're closer to the mountains, farther from the mountains, different altitudes, different microclimates, we have iron rich soils, we have limestone rich soils, we have volcanic soils — every kind of terroir. Should Argentina be experimenting with other varieties, other blends? Yes, and we are.

Our family is very interested in other regions which might have more water availability because Mendoza has pretty restricted water from the glaciers of the Andes, which are not becoming bigger. In fact, they're shrinking. We've looked at La Rioja, Argentina. We have a region called La Rioja, just like in Spain and it’s to the north of Mendoza. We are also planting vineyards in Patagonia. We're finding other regions where Malbec might do well, but maybe Bonarda does better or Garnacha does better. We are experimenting with other varieties. There's also some historic varieties in Argentina that have not been promoted enough, like Torrontes, the white wine of Argentina. It's beautiful.

Bonarda makes delicious wine. It used to get confused by the Italians with Dolcetto because it has a very similar profile. It's light and drinkable and delicious. Blended with Malbec it’s fantastic. Then there’s Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc, not that much is planted in Argentina, but it can give some interesting wine. Semillon has been planted in Argentina since the 19th century and can make some beautiful wines. And most people don't know this but there's a ton of Chenin Blanc planted in Argentina and it makes beautiful wines. I think you will see other things from Argentina. I don't think it's either that or Malbec.

Can you tell me a little bit about your joint venture with Lafite Rothschild for Bodegas CARO?

In 1999, we started talking with them about a partnership. We actually met in New York, at the New York Wine Experience, with the Domaines Baron de Rothschild team with the Baron de Rothschild. They were a little scared to do something in Argentina because of the political situation. They already had Los Vascos in Chile. My father persuaded them to come and visit us in Argentina. They loved the Cabernet and the Malbec.

This was 1998. ’98 was a crazy vintage. We had el niño. We didn't make any of our top wines. We started talking in 1997/98, but they came in 1999. They loved the Catena wines that we already made. That's when the talk of the partnership started. Then the first wine was made in 2000. It was made at Catena, at our winery. A few years later, Bodegas Caro moved to this very historic, very beautiful building in the city. It has these underground cellars. It's the most beautiful winery. It's old Italian Renaissance style. We've been making the wine there ever since. It's been 20 years of making that wine with the Lafite Rothschild family. It's been an amazing journey to be working with them, who make possibly the most famous wine in the world, as partners.

It's a very easy relationship because we're both very quality focused. We're always thinking about quality first. Have we made the wine well enough known around the world? Probably not. I'm often surprised that people don't know about Bodegas Caro. It's such a beautiful wine. It ages so beautifully. It's in the typical Lafite Rothschild fashion. They're not big marketers, promoters. They kind of make a great wine and then wait for it to be sold. Actually, the wine is doing quite well. We don't produce that much. It's not one of those projects where we're trying to make it into something gigantic. We want to just make some beautiful, really good wine. I think that's what we've done.

How much do you make of it?

The top wine, the Caro, is between 3,000 and 5,000 cases a year. That's quite small. Then there's Amancaya and Aruma that are 20,000 cases each. It's really a pretty small project.

You wrote a book about the wine country of Argentina. Why do you think it’s a great tourist destination?

My book is Vino Argentino. It was published by Chronicle in 2010. Most of the information is up-to-date, but some of it isn't. First of all, Argentina is such a beautiful country. We have every kind of geography. We have jungles to the north with monkeys and penguins in the south. From a natural point of view, there's so much open land. It's the seventh largest country in the world. It has a population of 50 million who are, half of them, in the city of Buenos Aires. This gigantic country with 25 million people. You can drive for hours and not see a house. You mostly see cows. The nature of Argentina is stunning.

My book is Vino Argentino. It was published by Chronicle in 2010. Most of the information is up-to-date, but some of it isn't. First of all, Argentina is such a beautiful country. We have every kind of geography. We have jungles to the north with monkeys and penguins in the south. From a natural point of view, there's so much open land. It's the seventh largest country in the world. It has a population of 50 million who are, half of them, in the city of Buenos Aires. This gigantic country with 25 million people. You can drive for hours and not see a house. You mostly see cows. The nature of Argentina is stunning.

When you go to Mendoza, to the wine country, you will be received with so much joy and happiness. Argentines are Italian and Spanish-style hosts. They love guests. They're hospitable by nature. In Argentina, you would never spend the weekend alone. Even the shiest person goes to an asado, our version of the barbecue. In Argentina, every person has, every Sunday, an asado to attend. It's like church. You would never miss your Sunday asado. It is either at your best friend's house, if your family lives in another province, or at your family's house. Even if you're having a fight with your cousin, you go. You are not allowed to miss this. That's how all family and friendship problems are solved in Argentina, with the Sunday asado. It's like the church for us. Some people also go to church, but that's in the morning.

Sounds fun. I need to make my way there.

You should. The other thing, with the devaluation, it's very inexpensive and this is the time to go. Your dollar will go very far.

Your father's philosophy was always looking to improve and to always try new things. What do you think is next for Argentina and for your winery?

The philosophy of elevating Argentine wine is at the core of everything we do. When I say Argentine wine, I mean Argentine wine. I don't mean Catena. We are very involved with everything that's going on — are there plagues, is there phylloxera, are there viruses? Everything to do with helping the industry. We have the Catena Institute of Wine that does research that is published in major publications. We collaborate with the University of Bordeaux, Burgundy, UC Davis, with the local universities. Everything we research, we share with other wineries. That is the main goal, elevating Argentine wine.

What is next for Catena specifically? What do we need to do to elevate Argentine wine? We need to keep our vineyards healthy. One thing that I'm investing a lot in is to study biodiversity. How to keep vineyards healthy through organic viticulture. I don't practice biodynamics but I practice what I call Catenamics. It's kind of a joke. It's one of these things. I said it as a joke and then it stuck. Catenamics is studying your own place. We're studying the micros. We're finding that one parcel next to another has different microbes in the soil. What are the effects of microbes? How do the microbes help the plant survive in this very dry climate? How will these microbes help us with climate change? We're already seeing with climate change dramatic changes in flora and fauna.

Some of the migrating species are missing their time to have food when they reproduce because whatever they eat, caterpillars, for example, and these are birds, but the caterpillars have already had their population explosion by the time the birds arrive. They're arriving too late. All these things are changing. We are trying to study this so that we can retain our way of life that is based in the vineyards. Mendoza vineyards is a way of a life. It's a cultural tradition. It's something that cannot be lost. In order to preserve it, we need to study it. Catenamics is understanding why the traditions of a certain place result in a certain flavor in a certain wine. The lives of people and how to preserve that. The reason that I call it Catenamics is because you need to study in order to preserve.

When you look at something like biodynamics, it's principles that were created 100 years ago in Austria. Why would I apply something from Austria to Argentina? I might study biodynamics and see why it works so well for so many people in Europe and then see a version of it that might work in Argentina. To me, it's important what the objective is. What is the objective? To preserve our way of life, our flavors, our places.

I think that in order to do that, we need to understand the local ecology, which is so different than the ecology anywhere else. That's basically my philosophy for the future. Really understanding the nature of the traditions, preserving the culture. We have people leaving every day to go work in the cities. They're not staying in the country. How do we reverse that?

Actually, living in the country is better. People don't know it. They think, "Oh, I'm going to go the city." Then they live in an apartment with 10 people and they make very little money. We're now doing days at the vineyard for high school kids in all the places where we have vineyards. We're actually getting a lot of them choosing to stay and live this rural life that is so rich and beautiful. They can still get Netflix! There's internet everywhere. You can work in the vineyard, have this beautiful country life, with Netflix.

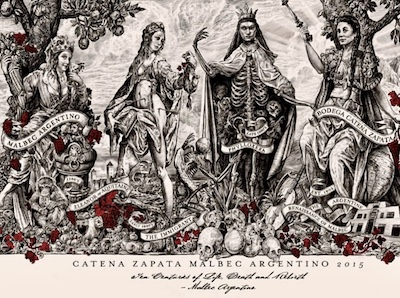

Can you tell us the story of the label for the Catena Zapata Argentino Malbec wine that you brought with you today?

Actually, my sister, who is a historian — she studied at Oxford and has a PhD in history — came up with this idea. I went to her and I said, "How would you tell the story of Malbec?” She said, "I think it would be boring to do a Power Point. Let's put it on the label." I thought, "Hey, that's good with me. I don't want to do another Power Point."

Actually, my sister, who is a historian — she studied at Oxford and has a PhD in history — came up with this idea. I went to her and I said, "How would you tell the story of Malbec?” She said, "I think it would be boring to do a Power Point. Let's put it on the label." I thought, "Hey, that's good with me. I don't want to do another Power Point."

She said, "Also, we have all these really strong women as part of the story of Malbec, let's make it about women.” Often, history is told by men. We want to tell history through the eyes of women.

The first figure is Eleanor Aquitaine. She supposedly drank Malbec at her wedding to Henry II who was 10 years younger than her. She outlived him by about 40 years. She lived until the age of 82. Back then that was very old, probably because she drank Malbec!

The second figure represents the immigrants that worked in the vineyards, like my great-grandmother. The reason for the arrows, besides being some of the San Sebastian imagery of the time that the label comes from, but also represents the sacrifice of the immigrants whose lives were so difficult when they arrived. This is the Bridge of Cahors, which is the birth home of Malbec in France and here are the boats that the immigrants came in.

Next is Madame Phylloxera, the aphid that forced all the vineyards to be replanted in the world. It mostly exists in the female form. We needed to have a villain. It's also a female one. That's why they couldn't eradicate it, because they couldn't stop the reproductive cycle. They couldn't find the males. That's why phylloxera is so difficult to end so here's all the dead skulls.

This is my sister. She wanted it to be me, but I said, “it's you.” This is the rebirth of Malbec. The hand of the skeleton is touching her. From death comes life. This is a map of the world and the pyramid, our winery. The artist is Rick Shaefer. He's from Connecticut.

One last question. Is it true that when you were in college, you used to do blind tasting with your friends with first growth wines using Riedel glasses?

Mostly it was with my father. My friends, if they were there, would come and be part of it. My father had told me, "Listen, Laurita,” (Laurita, he calls me) “When I come to the US, I need you to buy some wines so that we can taste together. I need to taste because I'm trying to figure out what I'm comparing myself against." He gave me his credit card so that I could buy all the wine I wanted.

Dangerous!

I wish I still had it. I used to drink a lot better wine then when I didn't have to pay for it. I still drink good wine, but I think a little more about it before spending. I tell you, when people would see me coming in at the wine stores, they would get happy. I would just fill the little cart.

My father also said, "You have to buy Riedel glasses because we need to taste from good glasses." Then we'd sit in my dorm room. We actually made a table with some wine boxes and we'd have the Riedel glasses and we'd have the wines. We'd usually slip in a Grange and a Vega-Sicilia Unico. Back then, those wines were cheap. They weren't cheap, but they were under $100, all of them. Usually, if there was a friend around, they'd do a little sniffing. We'd do that with my father every time he'd visit me. My father's visits were very popular.

I'll bet — how fun!

Read poetry by Laura Catena in Dorothy Gaiter and John Brecher's Grape Collective article, Château d’Yquem and the Sweetness of Laying Down Wines for Children.

Read more on the the history of Catena Zapata in Christopher Barnes' interview with Catena Zapata winemaker Ernesto Bajda.