The Vietti winery can trace its roots to the 19th century. It was at the beginning of 20th century that Vietti offered its own wines in a bottle. The winery is based in the village of Castiglione Falletto, in the heart of Piedmont. As well as being famous for single vineyard bottlings of Barolo, it helped make the native Piedmont varietal Arneis popular. In 1990, Luca Currado joined the family business as winemaker after working at California's Opus One and and Bordeaux's Mouton-Rothschild amongst other wineries. Grape Collective talks to Vietti winemaker Luca Currado.

Read Joshua Aranda's companion piece on Barolo.

Christopher Barnes: Luca, tell us about Piedmont, what is the history of the region?

Luca Currado: Piedmont is one of the oldest wine regions in Italy. It's very fascinating and very incredible, the history of viticulture in our land. The first traces of viticulture go back to Roman times, about 75 years after Christ. Basically they found there are traces of shipping wine from Alba. Alba is the major city of the Barolo region in Langhe. It was Alba Pompeia, so a Roman city. There was this Roman general called Plinio il Grande which means Plinio the Great, or the Tall. He was, of course, a short guy but with a big ego as was the case with many Roman generals. He shipped the "wine of the fog," as it was called, from Alba to Roma.

Why the wine of the fog? Because Piedmont means "the foot of the mountain." This region is 180 degrees surrounded by the mountains, the Alps. The highest mountains are between Piedmont and France, and Piedmont and Switzerland. These mountains, they do a lot for us. They collect a lot of snow for the winter time. They protect us in the summertime from the heat but also, in the fall, they collect a lot of fog. When we harvest the Nebbiolo, it's on the hillside with all these beautiful rolling hills with all these Medieval castles on top.

In late September, early October, when the Nebbiolo grapes are ripening, we start to see this fog that grows from the bottom of the hill from the flat going up to the top of the hill. We wake up in the morning and see just the castle outside of this ocean of fog. It's really scenic.

Why the wine of the fog? Because fog in Italian is "nebbia." Our most important grape variety is Nebbiolo because it's the variety that's ripe when the fog rises up the hill. I think it's a fascinating story because it really tells us that it's one of the most ancient varieties of Italy.

The Romans found the grape in Puglia, the heel of the boot of Italy, when they arrived in Italy from the Greece. The Romans were very interested in doing something with this grape, this fruit. They made the first wine. At the time, it was similar to a vermouth. It was not the wine as it is today because they didn't know how to preserve and fortify it. They were adding herbs to cover the defects of the wine.

Then the Romans brought the vines with them when they conquered Italy, France, Spain, Germany, and England. They used to plant the vines before they would plant the tent because they wanted to make their wine for their happiness. Many of the important wine regions of Europe belonged to the Romans at the time, like Burgundy and Champagne. They transported the grapes to France, Spain and England also.

I have friends that have a winery in England and they told me the history of the first planting and it goes back to the Roman times. Alsace, and in Champagne, all the caves and the winery are used to store Champagne. They were Roman caves. The Romans built them to extract the stones to use for building.

In Piedmont, the Barolo region is one of these areas where the vines from Roman times found the perfect microclimate conditions and thrive there even today.

Barolo is the most famous region in Italy. It's the region that people talk about when they talk about the top wine regions in the world. How did that happen, how did Barolo become the standard barrier of Italian wine?

My friend in Montalcino will be not very happy about that, but...

But Montalcino, but Montalcino is a fairly recent...

No, absolutely, absolutely, no, you're right, I'm kidding. Absolutely, the history, first of all because it's a very old history but in Italy there are other regions as old as the Barolo region. One very important thing to understand is that Italy is one country, and it's a very old country, from the Roman times, Rinascimento. But it's one country and has seen only one flag since about 160 years ago when the king of Savoy, the king of Italy, conquered all of Italy.

Before it was seven different countries with seven different cultures, different languages, food and wine. This is the reason that the biodiversity of the wine in Italy is extraordinary. In terms of cuisine, we cannot talk about Italian cuisine because it's a concept that doesn't really exist because what we eat in Piedmont is very different than what they eat in Tuscany, what they eat in Naples. Piedmont was a Savoy kingdom, Torino was the capital and the king of the Savoy. The Savoy in the old times was not only Piedmont, the Liguria, the Riviera in Sardinia in Corsica, but it was also French Savoy, up to part of the Côtes du Rhône and Côte d'Azur.

The Savoy family were very ambitious people. They always tried to compete with who was making the best food, making the best wine. This is why the culture of quality in Piedmont, the history of quality in Piedmont, was very strong. This is the reason, for example, even the Piedmontese cuisine is considered one of the most refined Italian cuisines, because it's kind of a mix between the simplicity, in the good way, of the Italian cuisine and the complexity of the French cuisine.

Ingredients are always fresh and seasonal, Italian cuisine is mixed with the creativity of the French cuisine. The king of Savoy was a huge promoter of our food and wine. Many say Barolo is the wine of kings, and that Barbaresco is the wine of queens.

You can say this is because Barolo is more masculine and Barbaresco is more elegant, but I think one of the explanations for this and this goes back to the love the king of Savoy had for our wine, is that he was giving as birthday gifts in the 1800s to all the kings of Europe one barrel of Barolo and one barrel of Barbaresco to all the queens of Europe. This is one of many stories.

One of the reasons that Barolo became so popular is not only because the history of quality is very deep, but also because it's a kind of wine that showcases the Nebbiolo grape variety. Just as Pinot Noir is one of the pickiest in terms of terroir, land and weather, there are very few regions where Nebbiolo grows very well. Pinot Noir is planted in many parts of the world but the real Pinot Noir is not made in many parts. It becomes so good and so special in just a few areas of the world.

It's crazy but for me, for example, one of the best Nebbiolos that I had in my life was from Australia.

The Vietti Masseria vineyard from which Barbaresco is made.

Really?

From the Adelaide Hills, because down there the sun conditions are incredible. Nebbiolo and Pinot Noir are two varieties that many people consider sister varieties. I don't know if they are long, distant relatives, this I don't know, but for sure they have many similarities. Think about the color, the elegance, the finesse of the color. Barbera, Cabernet, Merlot are much more deep and rich in color. Some characteristic of the region, these rolling hills where there are some corners of these hills that we call Grand Cru or vineyards as in Burgundy, where the quality that these small parcels give to the wine is fantastic and is why vineyards that are known for over a hundred years are so special.

Barolo is a wine that's known for its aging potential. What are some of the oldest Barolos that you've tasted and how did they change over time?

I'm in a very old winery and am lucky to have a collection of very old bottles of Barolo from late 1800 to early 1900. It was an emotional experience drinking this wine and going through the evolution of the wine, let's say, for example, from classic style Barolo, more traditional Barolo.

When you make Barolos they are very powerful, very intense, and very severe. The tannin profile is very intense, the nose is very reserved, it's never a wide wine because like the great Pinot Noir, when they are in the young stage, they are more narrow. With time, the volume widens as the molecules polymerize and they get together and the wine become richer and more powerful, more intense, longer and wider. Just like with many Pinot Noirs, at the beginning we go from stages of four or five years of more fruit personality, let's say darker fruit, more acidic red fruit.

After time they start to lose a little bit of this fresh fruit characteristic and go more to one of the notes that I like very much in Barolo, and that is this violet note. Sometimes I see this intense flavor and it's amazing. It goes from dry flower, dry fruit, potpourri, a lot of dry roses in some parts and then after 10 or 15 years of evolution these notes turn more to leather and white truffles. In some Crus they have very strong white truffles.

The Vietti Casinetta vineyard home to Castiglione Tinella

Let's say it's a wine where the maturation in the first year is pretty fast, let's say, compared to other varieties. They start to lose a little bit of color at the beginning, but then it stays stable for long, long time. Sometimes the color of a 15-year-old Barolo is similar to a 30-year-old Barolo, because all there is to lose in terms of color, you've already lost. Ageability depends because for me one of the good things about wine passion and wine emotion is that it's a personal thing. What I find good maybe is terrible for you, and what is good for you maybe is terrible for me. What I think is ready to drink, maybe for you is very closed.

This is the fantastic thing because we can read many descriptions, we can follow many books and publications but at the end of everything we are the judge ourselves of our wines. I can say that I felt great emotions from old Barolo. I had recently a very good '55, '58 of Barolo, a '61, and a '64, but I had different tasting emotions from very old Barolo.

I think years and years ago, one of the best emotions that I had from a bottle of Barolo was at a dinner in a very tiny trattoria, in the village where I am, Castiglione Falletto, and every year with a group of producers, we're a very small group of friends, we get together for the Christmas party so it's an excuse to get together to talk and drink some wine. Every year, we say okay, this year we drink Champagne or this year we drink I don't know, Riesling from all around the world. That year we said okay, let's bring some older wine from your cellar.

We arrived at the restaurant and everybody brought an old bottle of wine, and it turns out they were all beautiful French wines, we enjoyed it, fantastic, you know, great. Then the restaurant is literally 10 feet away from my winery. I was the lucky one because I didn't have to drive a whole lot, I was the one that could drink more than the others. I said, we are seven Italian producers, we all drink beautiful French wine, absolutely, so I ran to the cellar and this is the thinking that you do when it's one o'clock in the morning and you don't know if you are too happy or you are already starting to get drunk.

I went to the cellar and the same year one of my uncles gave me a bunch of bottles that belonged to my grandfather, who I never met because he died before I was born, and he said to me, look I know I have these bottles in my cellar that your grandfather gave to me, I don't know if they are any good. I didn't have any expectations because who knows how they stored the wine, if they had the right temperature and everything.

So, there was 1905, 1902, 1900, so I took the first bottle that was there full of dust and I put it on the table. Everything stopped. Every producer got in on it. One was rinsing the decanter, the other discussing how to open the bottle, we need to decant, we don't need to decant, which kind of corkscrew, which kind of glass, everybody was very proactive. Then we had this bottle, immediately when we pour and Barolo is very, very strange, because it's different than many other wines. Even the old wine they liked decanting because they always have a sort of cover that gets oxidized and once this light cover goes away, because with aeration, it goes away, we discover beauty below.

For sure, the wine anyway was old but the emotion of having this glass of wine that my great-grandfather made, my grandfather that I never met, was like sharing a glass of wine. It was a cultural shock for me. I always get goosebumps when I remember this story because it was like having the glass of wine with a phantom for me. I don't know, I do not have a crystal ball, plus I have people that like young Barolo and they hate old Barolo. I have friends and collectors that only drink old Barolo. It's up to the consumer to enjoy.

Luca, your family is the oldest winemaking family in Barolo. How is it to be part of such a tradition? Is it something that is a big responsibility on you?

Yeah, it's very heavy, but being one of the oldest estates, oldest families, is a big responsibility because when you start, when you are young you are braver, more stupid. But then you know, you surely feel that you have to bring the generation to another level, to another step, to evolve, because yes, we are a traditional producer. My father was always telling me that tradition is not a static word, it's a word that evolved with the time and with the year, adapted it to the vineyard, to the cultivation, to the climate, to the vintages. Evolution goes from father and son to the nephew.

Yeah, it's a big responsibility, absolutely. I think if I didn't feel that, I would be a stupid person, because the previous generation, somebody in my family did something unique, my great-grandfather. It's a funny story because in 1870 my great-grandfather left Italy because the oldest brother was following the vineyards and he came to America and he lived for 35 years in Boston. My grandmother, she was born in Quincy, Massachusetts and then in 1917 the other brother in Italy that was following the vineyard, he died, so all the family from America had to come back to follow the estate, and when he came back, he was a farmer, but he was an engineer also.

He worked, lived, and traveled overseas so he was one of the first that understood if he wants to make something special he needed to buy, to source the best grapes from the good vineyards. The good vineyards are the vineyards that today we call Grand Cru, and he was going with his horses and cows from one village to the other, to work on the parcels, the plots that were the best ones that he liked. I think it was one of the most important steps for my family.

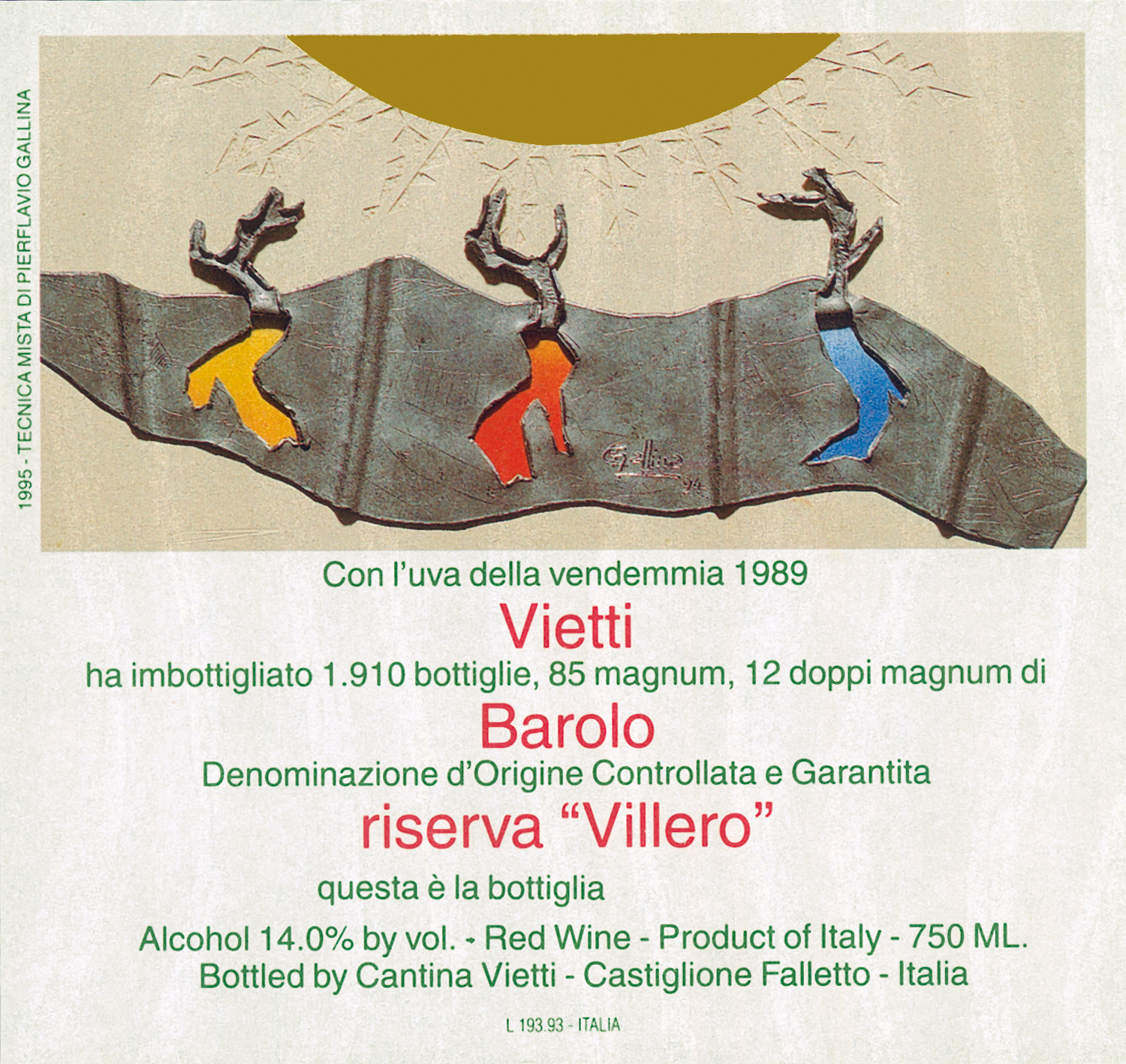

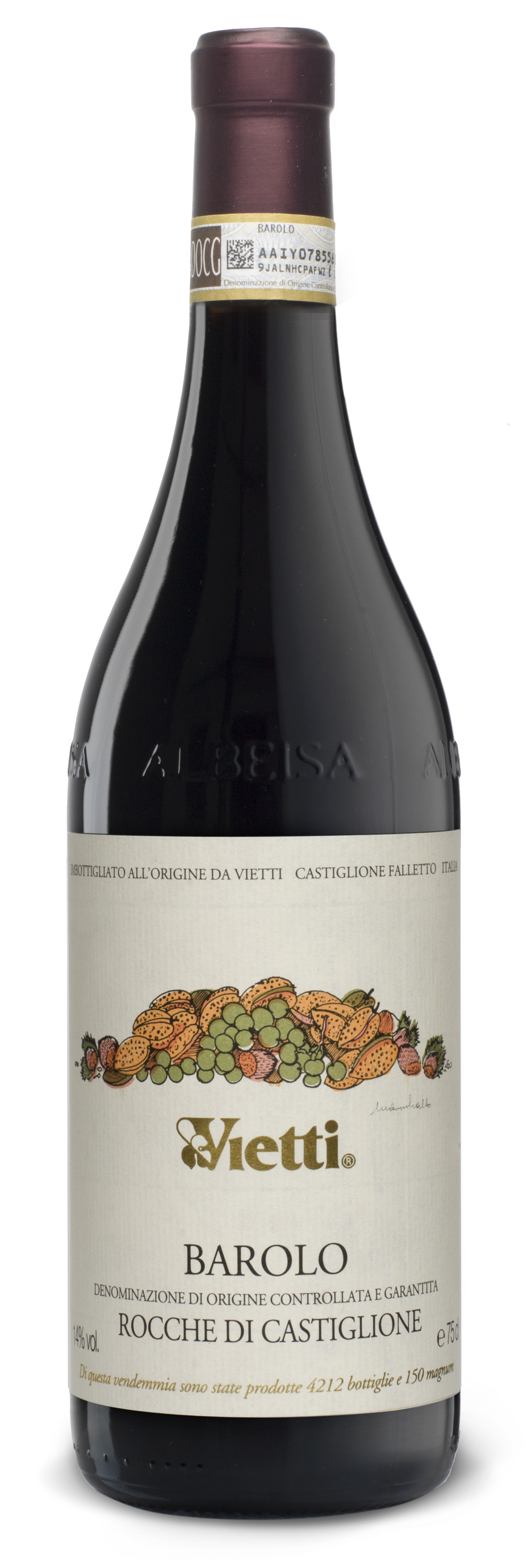

My father was the generation that was the first to make a single vineyard cru vinification Barolo. Last year with the release of the 2011 Barolo Rocche which was for us the 50th anniversary of the Barolo Rocche because in 1961 my father made along with another producer one of the first interpretations as a Burgundy terroir let's say, of the Barolo. He rescued from extinction the Arneis. Arneis today is one of the most popular white wines, not only of Piedmont, of Italy. It's huge, it's the fashion, it's one of the most modern white wines, and everything was created from him, because when he started as an experiment, there were less than 4,000 vines existing only.

There have been many many steps, in many many generations, so my generation is not going to ruin everything that happened in the past.

In terms of change though, have you changed much or are you very focused on keeping things as they were?

Like I told you before, the word tradition doesn't need to be, it means evolution and not revolution. It means that you need to learn every year from the errors that you make and not repeat the same ones or understand from some of the experiments go well in the vineyard, in the winery to absorb what you can really have, adapt it to the climate, adapt it to the climate change.

Yes, for sure some things are different, but the guidelines are more or less is the same so we will always be a little bit more traditional producer, so more old school.

Talk about global warming, is that something that's very noticeable in terms of the wine making right now and have you had adapted to the change in climate?

Yes, I think of it, very important because in 1980 we hired help for the harvest in early November. In recent times, we had a harvest in 2003, we harvest on the 28th, this was an extreme. The 28th of August.

Wow.

But normally let's say we lost one month, I think. It's like saying every pregnancy, instead of nine months, they all become eight months, because more or less the bud break is the same but everything is more shorter, more compact, so it's reality, it's not bullshit, it's reality.

You talked about being a traditional producer, but there's a trend to modern wines in Barolo, talk about that, what are the differences between traditional and modern?

Traditional and modern, it was, years ago, a much bigger fight. Today, there are fewer issues. Actually today many of the more modern producers of one time have adopted more traditional production methods. But anyway, it is a different interpretation of our grape, Nebbiolo, because Nebbiolo grape is a variety that has a lot of tannin. If you are lucky to own a Grand Cru vineyard like we have a Rocche vineyard, and in Brunate, Lazzarito,Villero, the grape always ripens fantastically because if not, we could not call it a Grand Cru.

The tannin profile of Nebbiolo is very strong so it can be very unapproachable when it's young. The modern producers understood that if they were making very very short fermentation, crushing the grapes and press the grapes before that certain quantity of alcohol is extracted and then so they didn't get all this tannin profile and then they put more in new oak, French oak to get the shoulder of the tannin but the tannin from the oak, not from the grape. That tannin is more sweet, more round, more approachable, more dedicated, more ready, absolutely which is a very different interpretation than by a traditional producer. During the fermentation wait, you get all the extraction and then you extend the maceration, which means contact with the skin. Many times we submerge the cap almost at the end of the fermentation like a French press for coffee.

With all the skin and the must, you have a long, long maceration and you wait until these tannins extracted during the fermentation get together, and then they become more round or more sweet, more long and then for sure you do not need the new oak because you already have good structure in the wine and the wine is aged more in large traditional cask of Slovenian oak, so new oak that doesn't give smell, doesn't give taste, doesn't give perfume.

And is it with the modern wines that they're easier to drink on release, is that sort of the point of them, that you don't have to deal with kind of the tannin backbone that may need some aging before it kind of opens up?

This is a bit awkward because I am biased, but absolutely, for sure, the more modern interpretation of Barolo, are wines that at a young stage they are much more elegant and approachable but also they age very well. I have had some very old modern Barolo, that age fantastically. The traditional Barolo has a tendency to be a little bit more severe, more classic, more delicate, more Burgundian style, if you want to use this word, compared to the modern.

So, over time they soften up.

It's funny because over time you start from two different positions and with age they arrive at the same point. It's very fascinating.

And you make 17 different wines?

Too much, why you want to remind me of this? I should make fewer, but yes, absolutely, 17 different labels.

17 different labels. And how is the terroir different in the different wines that you make?

Of these many labels, we have only four grape varieties, five with the moscato. We have always loved the difference in the terroir; we were the first to make single vineyard crus in the Barolo, and now we make four Grand Cru wines. I think of Barolo and Burgundy as the two region where the taste of terroir is so distinctive.

We do this also with the Barbera, not only we have Barbera from Alba and Barbera from Asti, but we have a different Cru, a different vineyard, vinification from Alba and Asti.

What is the difference between Barbera di Asti and Barbera di Alba?

To make it simple, I always compare it with Napa and Sonoma. Two beautiful wine regions with great grapes of Napa and of the Sonoma, and great wines but with different personalities. Alba for me is always very powerful, very intense Barbera, but always very elegant, very delicate, very floral, Barbera.

Asti, is powerful, intense, more masculine, more meaty, more robust Barbera, also in the younger stages sometimes, little bit rustic, little bit more aged. Alba for me is always the Grace Kelly of the Barbera, a wine that you want to dance with and Asti is the Angelina Jolie of the Barbera, wine that you want to have a fight with.

That's terrific. Both very lovely ladies.

Absolutely, absolutely.

In terms of making wine today, obviously we live in a very different culture in terms of social media, in terms of marketing, have you done anything different in terms of promoting the wines and getting the wines out to the market?

I love being in the vineyard, because there is no telephone, there is no email, there are no people to break your balls, you are there focused in your vineyard, thinking about your grapes and your wine. The silence of the vineyard is fantastic. It's beautiful. Much less so in the summer time when it is too hot. Or too cold in the winter with the snow.

I really like meeting and seeing the consumers, because you see their appreciation of your wine or maybe not, but at least you see the reaction that they have and if they like it, it's the best booster, and you bring home a big charge of energy to work positively in the vineyard. Today with the social media, video, Twitter, Facebook, everything is so immediate and it's fantastic, I like very much being in touch with my consumers, it's great.

People ask me when to drink this bottle or tell me that they didn't like a vintages or prefer other vintages or ask about food pairings, it's great, it's a big community. We drink wine for passion at a certain level. Sharing your passion with people that follow what you do is fantastic.

How does the climate affect your vintage in Barolo and what are the sort of extremes that you have to fight against?

As I said when we discussed global warming, we had more severe, higher temperature vintages. What is crazy is that, despite Piemonte's being so very north of Italy, in the 1950s, we had only one or two good vintages. In 1964, in 1975, in 1997. In the 2000's, we probably had only one vintage that was poor. More recently, the consistency of the vintages has been incredible.

Certainly all are different but, if I take the last six, I could say 2002 was a disaster, a lot of hail, storm, rainy, humid, at least in the majority, 99% of the Barolo region. 2003 was very very hot, a vintage that I hope not to do again, because I had to come back from vacation to make the harvest. Other than that, some were warm, some were fresh but the most elegant vintages were 2008, 2010 and 2012 and the most opulent vintages, 2009, 2011 and 2013.

-----

More on Piedmont?

Watch our interview with Angelo Gaja.

Read about the cooperative Produttori.

Watch the interview with Raffaele Boscaini of Masi.