Mike Grgich's life is a great American story. A young man escapes from communism in Croatia, traveling to America via West Germany and Canada. In America, years of hard work see him raising himself from cellar hand to co-owner of his own major wine label. Oh, and he beat the French. He was the creator of the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay that won the 1976 Judgment of Paris, a blind tasting where the top French wines squared off against Californian wines. The shocking victory helped to put California wine on the world wine map and changed the global wine market as a whole. The 1973 Chardonnay that Grgich crafted is included in a Smithsonian exhibition "101 Objects that Made America" alongside Abraham Lincoln's hat, Alexander Graham Bell's telephone and Neil Armstrong's space suit.

Grgich talks to Grape Collective about escaping communism, finding paradise in Napa Valley and his distain for Bottle Shock, the movie that dramatized the 1976 Judgment of Paris.

Mike Grgich: My mama had 11 children, and I happened to be the last one. I was baby, and mama kept me on breast milk until two and a half years. I thought I would be on breast milk forever. However, one day I misbehaved, and mama said, "No more milk." I say, "Mama, how I'm going to survive? I think I'll need milk forever." "I'll switch you from milk to wine."

We had a vineyard and a winery and we had plenty of wine, so she would make half and half, half water/half wine, which we call bevanda. There was one wooden container always on the table just made for me. Other people drink whole wine, but I drank half-and-half until I was about five. I think about five I started to go with the whole wine.

That kept me in my whole life … wine, a best friend of mine.

Grape Collective: When did you start working in the fields and learning how to make wine with your family?

Mike Grgich: In our big family, when it was harvest, everybody participated. When we had a harvest and I was still young, a year or two, they put me in the big tank from which I could not escape, so that I can work. There were no babysitters in those days.

Once in a while they would dump some grapes from the top, so I was safe, I cannot escape, they could do the job, and if I get hungry I can eat grapes or drink grape juice. I was safe and supplied.

That was my beginning, and I started to stomp the grapes at the age of three, because that was …we didn’t have electricity or machinery, so juice has to come by some force, and that was either by the feet or by the hands as the only energy.

Grape Collective: When you left Croatia in your youth, you came through Canada … is that right?

Mike Grgich: I left Croatia because I didn’t like communism, and while I was a student at the University of Zagreb, studying viticulture, in last year, fourth year, one of our professors visited California on sabbatical leave. When he came back, we all wanted to know how California looks because, during communism, we were told everything was wrong in America.

He looked around, because he was afraid that secret police was waiting so he put hands in like this and said, "California … paradise. Paradise!" "My goodness," came to my mind. "Why shouldn't I walk into paradise?" I decided, "I'm going to go to California."

Under communism you couldn't get a visa, you couldn't get a passport. I worked on it, and worked on it, and worked to collect some money so that I could pay my way to America … I collected $32. When the day came to go, I heard that, on the border, they removed all foreign money. I thought, "I have $32 I can get to America, but if I bring this $32 through the customs I won't have anything to get to America."

I went to the shoemaker, and I got the idea to take sole of my shoes and plug the $32 in, and put the new sole over it so nobody would know. We came to the border, and they took one lady away; she never came back. I stayed on the train, and I passed the border. I said, "Never again I'll come back".

I did go to West Germany for four months. After four months I got nowhere, I applied for a visa for the United States. It was very hard to get, so somebody told me, "You can go to Canada. I went to the Canadian consulate, and they said, "Do you want to go tomorrow?" I said, "I possibly need money to pay for the transportation." They said, "Yeah, you have to do that."

I had in America a brother-in-law in Washington State, and I called him and I said, "Send me $150." That would pay for my train from Germany to the ship, and in Canada from the East Coast to Vancouver … $150.

I was prepared to go, but that money never came. The people I was staying with they paid for my ticket, and had a party in the evening. I was so ashamed that they did so much for me.

In the morning about 6:00 am, the postman came with $150, and I paid them back. I was happy.

Then I arrived in Fairfax, Canada, I had received a visa to come to Canada and go to Yukon to cut the trees … anything just to get to America. After two and a half years I got an America visa.

In 1958 on 15 of August, I came to Napa Valley … paradise. Can you imagine how happy I was?

Unfortunately I came by bus from Canada, Greyhound Bus. I was the only one at the end of the bus trip, and I was told by the people that I was to work for that they were to come and pick me up. But nobody was there, 10 pm in the evening. I looked around. I looked for a hotel and I paid $2 for a night, and how I was scared that if they didn’t come to pick me up, that I would have to pay another $2 the next evening.

Grape Collective: Before Chateau Montelena you worked for Mondavi … is that correct?

Mike Grgich: I worked before Chateau Montelena at Christian Brothers in St. Helena one year, 1917, and then I heard about André Tchelistcheff, that he was called the Dean of California winemakers. He taught all these winemakers in Napa Valley how to make good wine … French style. He was an immigrant from Russia, had escaped the war and went to Czechoslovakia, and studied agriculture, and then came to Croatia. In Croatia he then got a scholarship go to the Pasteur Institute in France.

People told me stories about André Tchelistcheff. I said, "I should meet that gentleman." I called him and he gave me appointment, and I look him here, short like me, but he had strong eyebrows. I tried to talk to him in broken English, and he started to talk to me back in perfect Croatian because, as immigrant, he was going from country to country. In Croatia he made a living by singing and dancing.

I know what is an immigrant because I am an immigrant, and he was an immigrant, so we found a common language. He told me, "Are we in paradise?" I worked with him nine years until he retired. After he retired I moved to Robert Mondavi, but I learned a lot from André Tchelistcheff because he was the dean of California wine, especially red wine … Cabernet, the BV Cabernet was the best in the world.

Grape Collective: What was it like working at Mondavi back then? He had just split from the family, he's been setting up his own winery. It must have been a fairly ambitious place to be.

Mike Grgich: I was becoming part of his family. Once in a while he would make breakfast, and we'd have breakfast together. Then he would set up a tasting of the wines, an American and French comparison, because he had idea that some day … because the Napa Valley would have good soil, good climate, good varieties, we can make wine as good as French.

However, it happened that his student … he wrote in the forward to his book … that it was his dream to make wine as good as French, but his students, Mike Grgich and Warren Winiarski made wine not as good as French but better that French. That was for me paradise … real paradise, and a sense of victory that is not possible to describe.

Grape Collective: Tell us a little bit about the Judgment of Paris and how that came about.

Mike Grgich: The English man who, in Paris, opened a liquor store, selling wine … a smart guy … he wanted to known how he can get publicity for his little store. The American bicentennial was coming up, and he felt that he might have a blind wine tasting for the French best Chardonnays and Cabernets.

They came and chose the wine. I had already beaten the French in a contest in San Diego. They chose my Chardonnay to go Paris. He brought the nine best judges in France and tried to get publicity, asking French journalist to participate. Nobody came. They thought that it is a shame for France to compete with small, poor California wines.

He contacted George Taber, a journalist based in Paris, and Tabor had nothing to do that day so he come over to the tasting. He was there, the journalist, watching what they’ve been doing, and when they started the scoring, first wines that were tasted were the white wines, so Chardonnay was tasted first in the morning.

When it all ended, the Chardonnay that I had made got 132 points … more than any French and any California Chardonnay. When they revealed the results, some of them tried to correct the scores, but Mr. Taber was there. He said, "No way. What is done, is done." Such a bad day for the French judges.

Then in the afternoon they tasted the Cabernets, and the same thing happened, that Winiarski came in first place - but he didn’t get 132 points, only 127, so my Chardonnay was the champion of the Paris tasting.

Grape Collective: That tasting … that tasting has had such a profound impact on American wine, specifically Napa wine. Did you understand the importance of the event, or did that only happen over time?

Mike Grgich: I wrote a little letter, which I'll give you to take with, that I summed it up … when preparation meets opportunity, that’s the luck. I did preparation. As a child in the tank, working with my family to pick the grapes, and they would dump some grapes from the top. From that beginning to studying knowledge in viticulture, to Mr. Stewart, to the Christian Brothers, to André Tchelistcheff, to Robert Mondavi … and then I came independent.

Mike Grgich: After the Paris tasting, the owner wanted to take over my job. He was a lawyer in Los Angeles, and he would come and tell me how to make wine before my five years expired. Before my five years expired I made the decision that I'm not going to work under the lawyer. With my knowledge and my experience, I'm going to look for some other way.

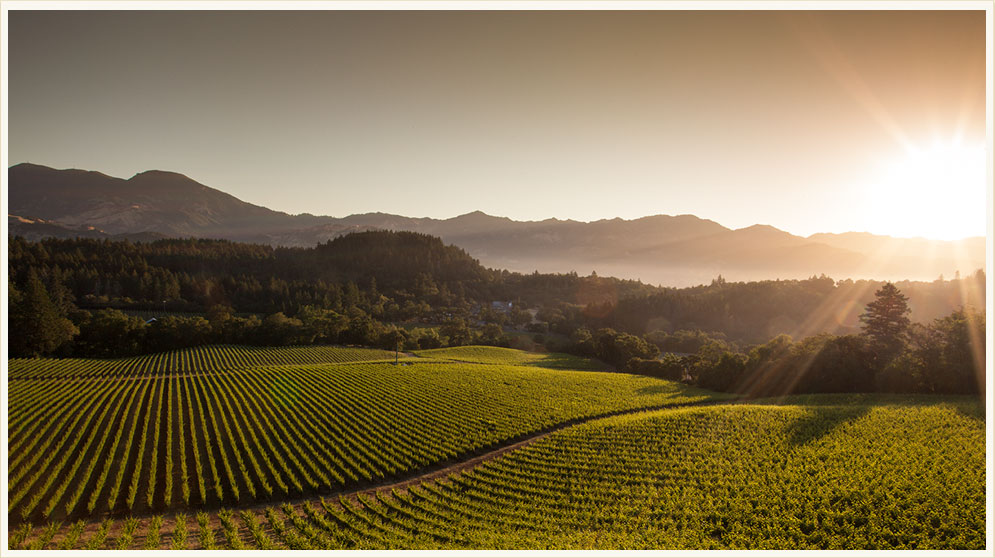

Mr. Hills, who used to have his brother's coffee company in San Francisco, they had sold the company, and he was looking for an investment. My name was already made as a winemaker after Paris tasting, so he wanted to make wines better than the French. He came to me and offered more than I ever could dream … 50% (Grgich Hills Estate pictured below). He put up the money, and I put in my expertise.

I had at Chateau Montelena 1% every year, and 5% after 5 years; but he offered me 50%. He is 25%, his sister 25%. I am a major partner. I have 50%.

Grape Collective: Regarding Bottle Shock..

Mike Grgich: The only three things are true about the movie is that Jim Barrett was Jim Barrett, his son Beau was Beau, and his wife, Laura was Laura. The all the other things were all a fabrication. When they showed me the script and I read it I said, "No, not for me." I even sent them a letter if they ever use my name I'm going to sue them, so it was not me in that movie. Barrett ended up looking as though he made the '73 Chardonnay.

Mike Grgich: I always joke, "If anybody makes the best wine in the world, that will be Grgich Hills." I give them encouragement so that they learn. We have the attitude in the winery that everybody has to learn something because my father, when I left my home at the age of ten to go for further schooling, he was poor. He never had money … producing for the family everything, but he had no money. He said, "Son, I don’t have money to give you, but I will give you some advice. In life remember: if you ever start working, do your best every day, and be sure that you learn something new every day, and that you possibly make a new friend every day so that, in 365 days, you will have 365 friends. No money can buy that.

My father let me go with that message into the world, and now I am repeating that to my daughter and my nephew … same thing.