Champagne is a region with a well defined and often strictly adhered-to identity. Its brand is luxury, built on the backs of large negociant houses making large amounts of very consistent sparkling wine in a region that is one of the world’s most challenging areas to grow ripe grapes. Champagne is famous for cold fronts, hail, and rain, causing mildew, rot, and many other vine diseases which are the enemy of the grape grower. Because of this most Champagne has historically been a blended wine - multi-varietal, multi-vintage, multi-vineyard - in order to achieve a reliable product year in and year out. While the obvious successes of these tactics may prove them a triumph to many, others yet criticize these practices for homogenizing a region of rich potential.

Other ways that local producers have mitigated the effects of a challenging climate have also come under fire. Fighting diseases via chemical intervention and covering up a lack of ripeness with an over-reliance on dosage (a common practice in Champagne of adding sugar to an otherwise finished wine to achieve balance) have been some of the common tricks that big Champagne houses use to achieve consistency. A little bit of warmth goes a long way in grape growing, and perhaps this is why the southernmost parts of the appellation have been ahead of the curve when it comes to some recent shifts in the region’s paradigm.

Other ways that local producers have mitigated the effects of a challenging climate have also come under fire. Fighting diseases via chemical intervention and covering up a lack of ripeness with an over-reliance on dosage (a common practice in Champagne of adding sugar to an otherwise finished wine to achieve balance) have been some of the common tricks that big Champagne houses use to achieve consistency. A little bit of warmth goes a long way in grape growing, and perhaps this is why the southernmost parts of the appellation have been ahead of the curve when it comes to some recent shifts in the region’s paradigm.

The effects of global warming have undoubtedly caused trouble across the winemaking world, but they have also potentially made more natural practices and a sense-of-place approach increasingly feasible options in Champagne. With temperatures having risen more than a full degree Celsius in the last 30 years in the region, harvest times have shifted dramatically, ripening has been less of a hassle, and many growers are needing less and less intervention. One such example can be seen in the growing popularity of non-dosage wines across the appellation, as growers find they can achieve enough ripeness to render the use of additional sugar obsolete.

Over the past few decades importers like Terry Thiese have championed small-production, more naturally focused, grower Champagne producers and put the spotlight on the value of variety - making room on the market for sparkling wines of place. And though top names still score top marks in sales, the big houses are taking notice of this shift, with even the famous Louis Roederer estate undertaking a conversion to biodynamic practices starting in the year 2000, and offering their first nondosage cuvee in 2006. These practices were already commonplace in Champagne’s less fashionable extreme south, an area where we find a dense concentration of producers whose focus on terroir and sustainability is not a response to market trends, but rather baked into their very ethos.

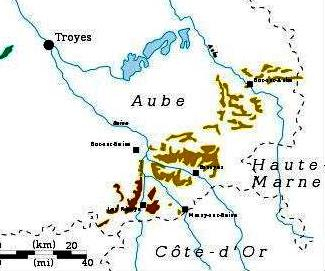

The Cote des Bars, residing in the Aube department, is closer to Burgundy than it is to Reims, enjoys similarly mild(er) weather, and showcases  veins of Kimmeridgian soils - the same soils that contribute to Chablis’ distinctive minerality. These climatic conditions may make organic and biodynamic practices more accessible than they have been in the northern reaches of Champagne, with less hazardous weather and a historically longer ripening season. For generations, grapes from the Aube have fleshed out the blends for negociant houses situated further north, adding fruit and depth but rarely being afforded a seat at the table on their own individual merits.

veins of Kimmeridgian soils - the same soils that contribute to Chablis’ distinctive minerality. These climatic conditions may make organic and biodynamic practices more accessible than they have been in the northern reaches of Champagne, with less hazardous weather and a historically longer ripening season. For generations, grapes from the Aube have fleshed out the blends for negociant houses situated further north, adding fruit and depth but rarely being afforded a seat at the table on their own individual merits.

The producers in the Cote des Bars are aided, in part, by the area’s lesser recognized reputation. Despite the area’s proven utility, the greater Champagne region sought to exclude the Aube from the official appellation limits. In fact, until 1927, it was classified as a 'second' Champagne zone. This history has left the door open for enterprising smaller houses to shrug the chains of tradition and experiment with a more terroir-focused style. Across the Cote des Bars can be found several estates who prefer single vintage over NV wines, prefer single varietals to blends, and prefer the personality-driven microclimates of single vineyard expressions to the consistency of broader sourcing. It is also a subregion in which we find some of Champagnes most dedicated environmentalists.

Dominique Moreau of Marie Courtin is one such producer. Located in Polisot, the young estate was established in 2005. Named for Dominique’s grandmother, who she refers to as a ‘woman of the earth,’ the estate has steadily garnered more and more praise for the last fifteen years. Since its inaugural vintage, Marie Courtin has subverted the traditions of Champagne, with their mission to produce monovarietal, single vintage, zero dosage wines using strict biodynamic practices. Moreau’s approach is spiritual, attuning herself to the energy of her vineyards via crystal pendulums in order to monitor grape development on the vine as well as other variables throughout the winemaking process. Her commitment to biodynamics extends well beyond the metaphysical, forgoing all chemical intervention and focusing on the rhythms of the seasons to determine when planting, pruning, and harvesting take place. All varietals are vinified separately, both primary and secondary fermentations are carried out on indigenous yeasts, and very little sulphur is used - if any at all. The resulting wines are dynamic, mineral etched, and brightly focused. A true, unadulterated testament to the terroir of the Aube and proving what attention to the sustainable health of vineyard land can produce.

One of the pioneers of these natural practices in Champagnes’s south is Bertrand Gautherot of Vouette & Sorbée. Gautherot planted his first vines in 1986 in the village of Buxières-sur-Arce at a time when the Aube was under-appreciated and underrepresented in the world market. He was certified in biodynamics by 1998, making him among the first in the region. While he didn’t officially bottle under his own domain until 2001, his early adoption of a certified natural approach and his commitment to the terroir of the Cote des Bars has made him particularly influential. With a “grower-first” mentality, Gautherot is soil focused, distinguishing his parcels by their Kimmerdgian and Portalandian soils - both soil types which are commonly found further south in Burgundy. While he prefers not to ascribe to some of the spiritual dogma often associated with biodynamics, his dedication to the health and sustainability of his vines is evident in the biodiversity he maintains on his property and reveals itself further in his distinctive wines.

As the environment continues to change and the effects therein shape the world around us, there are several stalwart producers across the globe who are striving for a less impactful, minimal interventionist approach to winemaking. In Champagne, Moreau and Goutherau’s efforts therein represent a particular type of rebellion - not only in their commitment to biodynamics, but also in their championship of a subregion whose voice has not always been heard, in their willingness to eschew tradition, and in their unabiding dedication to the land that fosters their singular wines.