I told my wife a man is like wine, he gets better with age. She locked me in the cellar.

They’re not quite the Rodney Dangerfield of wines, not like Müller-Thurgau by any means, but they still don’t get the respect they deserve: Pinot Grigio and Beaujolais. We had some recently that reminded us how good they can be.

Pinot Grigio has been the best-selling white wine from Italy for a long time. However, as day follows night, popularity bred mediocrity -- tankloads of insipid, watery stuff, pale imitations of what good Pinot Grigio can taste like. The best can be soulful, with juicy, ripe, swoon-worthy fruit, acidity that dances on your tongue and a rich foundation of minerals.

Following a recent tasting of the 2017 Attems Pinot Grigio Ramato from the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region in northeastern Italy, we can now add this descriptor to some: a copper hue. Centuries ago, Italians referred to Pinot Grigio as “ramato,” or coppery, the color of the wine after it has been kept in contact with the Pinot Grigio grape’s dark skin. At Attems, that means about 10 hours of a cold soak, after which the grapes are softly pressed and left with juice and skins in contact for about a day. After that there’s fermentation in steel tanks and four months on lees in barriques to add some depth. Attems is an ancient hilly wine estate in Collio in the province of Gorizia, with the Alps to the north, the Adriatic Sea to the south and marl and sandstone soil.

“Ramato was a name going back a long time. My grandfather made it, too,” Attems’s winemaker, Daniele Vuerich, explained on a recent visit to New York City. Vuerich, 35, grew up in the Friuli-Venezia region, which is renowned for its white wines. He joined Attems in 2011 after stints at wineries in Napa and Sonoma (Atlas Peak and Buena Vista), in Australia for Domaine Chandon and in Italy and New Zealand.

“We are reinterpreting it in a modern key. You can feel a lot of the flavor with the skin, without a long maceration. The aromatic compounds are very important, and the color. I’m really proud of it. I think there is freshness and balance.”

In our notes on this pinkish-orange wine before we met Vuerich, we wrote, “Remarkable. Not afraid of true earthiness. Not a simple, gulpable Pinot Grigio or a simple rosé. Watermelon, strawberries, and lots of wet stones. Very drinkable but not simple. You could serve this with a rare steak. It’s really quite something. Grapefruit with peels. Juicy and not a hint of sweetness. No bubblegum. Pork!”

(Dorothy J. Gaiter with Attems’s winemaker, Daniele Vuerich)

The Attems estate, on the border of Slovenia, was founded in 1106 by the Attems family, some being members of the Holy Roman Empire in the 17th century and others winegrowers, aristocrats all. In the second half of the 20th century, Count Sigismund Douglas von Attems governed the estate, and in 1964 founded an influential consortium of winemakers, the Consorzio dei Vini del Collio, to promote the wines of Collio. He and the consortium helped the region receive DOC status.

As it happened, Count Attems went to the University of Florence with Vittorio Frescobaldi and when the Count was upgrading his family’s estate, invited Frescobaldi to invest. In 2000, two years before the Count died, he sold a majority share of his business to the Frescobaldi family, aristocrats and winemakers for more than 700 years. In 2011, according to Wine Spectator, the Frescobaldi group, headed by Lamberto Frescobaldi, the son of the Count’s former classmate and 30th generation winemaker, purchased the remaining 30 percent share of the business. It is the Frescobaldis’ first holding outside Tuscany.

“Lamberto didn’t want to make a Tuscan wine in Friuli,” Vuerich said. “He wanted to make a wine from the region, true to where it was grown.” Attems released its first Ramato in 2007, Vuerich said, and it has been a runaway hit.

We found the 2016 Pinot Grigio ($17) a revelation, too. “Surprising nuttiness and weight. A touch of oak maybe, but not too much. A real seriousness of purpose, mouth-coating and pretty rich. Cashews, tangerines. A food wine, not a Pinot Grigio by the bar.”

We hadn’t had a Pinot Grigio with that much character in a while. “Some in our region make other styles,” Vuerich said, diplomatically. “Depends on which is the way you like it. I must be proud of what I do when I present my wines. There is some creaminess but not sweet. It has a dry finish. If you find the right way to plant it, in sandstone soils, it can give you its character. It has a medium light body but it has presence. Barriques add complexity.”

Attems also makes an excellent Sauvignon Blanc and its top of the line white, Cicinis, is a savory Sauvignon Blanc that spends eight months in barriques and egg-shaped cement tanks. We were sent the 2015 but the soon-to-be released 2016 that we had with Vuerich really got our attention. We’d wait for that vintage.

On to the underappreciated red: Beaujolais. If there is a more versatile red wine, we haven’t met it. Made from the Gamay grape, in the hands of a winemaker of integrity, it can more purely reflect where it was grown than many other grape varieties. That’s why the 10 Cru Beaujolais, 10 appellations in the Beaujolais region in southern Burgundy, market their wines with the appellation’s name on their labels: St-Amour, Juliénas, Chénas, Moulin-a-Vent, Fleurie, Chiroubles, Morgon, Régnié, Brouilly and Côte de Brouilly. Each has a different character and many are age-worthy.

(Dorothy J. Gaiter with Frédéric Weber cellar master of Château de Poncié)

We’re not going to dump on Beaujolais Nouveau, the just-released-in-November wine that celebrates the new vintage—dumping on it is so yesterday. There’s a time and a place for every well-made wine. What we’re writing about here, though, are the crus, in the northern part of the Beaujolais region. (Dottie wrote about Beaujolais here: )

Of the 10 crus, one of our long-time favorites has been Fleurie, which Dottie identifies as especially feminine, as opposed to, say, the more muscular Morgon. Fleurie can be elegant, with a heady nose of blue flowers, with earthy, classy and piercingly pure, mineral-laced flavors of black and blue berries. On a hot day recently, we found Fleuries of that description at a garden party hosted by Frédéric Weber, cellar master of Château de Poncié and the famous, large Burgundy merchant-winemaking enterprise Bouchard Père & Fils, which are both owned by the Maisons & Domaines Henriot Group.

Since we were not familiar with Château de Poncié (photo right), a Fleurie producer that dates back to 494 AD, we focused on its wines. Weber, who joined Beaune-based Bouchard in 2002, was born in Alsace and before Bouchard, he worked for another wine company in Champagne and the Rhône Valley. His grandparents lost their Alsace vineyards during World War II. He lives in Ladoix, a region in Burgundy that produces heavenly wines. (We had a 1978 red Ladoix at L’Espérance, a life-changing restaurant in Vezelay on our first trip to France in the 1980s.) Weber holds degrees in engineering and oenology and his wines are as precise as you’d expect of someone with that type of training. To demonstrate how well Beaujolais can age, he poured the 2010 Château de Poncié Le Pré Roi, though it is not available for purchase. It was lighter in color, as might be expected, but had lots of acidity and still fragrant fruit.

Since we were not familiar with Château de Poncié (photo right), a Fleurie producer that dates back to 494 AD, we focused on its wines. Weber, who joined Beaune-based Bouchard in 2002, was born in Alsace and before Bouchard, he worked for another wine company in Champagne and the Rhône Valley. His grandparents lost their Alsace vineyards during World War II. He lives in Ladoix, a region in Burgundy that produces heavenly wines. (We had a 1978 red Ladoix at L’Espérance, a life-changing restaurant in Vezelay on our first trip to France in the 1980s.) Weber holds degrees in engineering and oenology and his wines are as precise as you’d expect of someone with that type of training. To demonstrate how well Beaujolais can age, he poured the 2010 Château de Poncié Le Pré Roi, though it is not available for purchase. It was lighter in color, as might be expected, but had lots of acidity and still fragrant fruit.

The 2015, our notes read, was “smooth, fuller, with apple-peel acidity and earthiness, minerals. Dark purple and bluish tint. Heady nose. Blackberries and black cherries, a whiff of eucalyptus.” The 2016 was “fruity and fun with lots of granite and stones underneath, not as stately, as well-knit and balanced, as the 2015.” The 2015 vintage was marked by drought, with an excellent though small yield. The 2016 growing season was better though hampered by frost and yielded again a small crop. We couldn’t believe these wines sell for a mere $20. The chateau’s higher-end Fleurie, the 2015 La Salomine, was elegant, tight and mouth-drying. It has a suggested retail price of $30, but wine-searcher.com puts its average price at $38.

Henriot’s purchase in 2008 of Château de Poncié’s property follows a trend of Burgundians investing in Beaujolais, which is far more affordable. Since its purchase, Henriot has invested a lot in replanting and resurrecting the property, which for a time was known as Villa Ponciago. Its soils contain pink granitic crystalline rock, and Weber brought samples of it.

Weber told us that at the end of the 19th century, Château de Poncié’s wines brought the same price as Clos de Vougeot, one of Burgundy’s most iconic vineyards.

What happened, we asked?

“Beaujolais Nouveau’s reputation,” he replied ruefully.

OK, we get it, but shame on consumers if they continue to confuse Beaujolais Nouveau with finer Beaujolais. It’s their loss. Ditto for forgoing Pinot Grigio forever because you’ve had some bad ones. Look for good producers like these and regions like these where the good stuff can often come from. Now have fun with wine this summer!

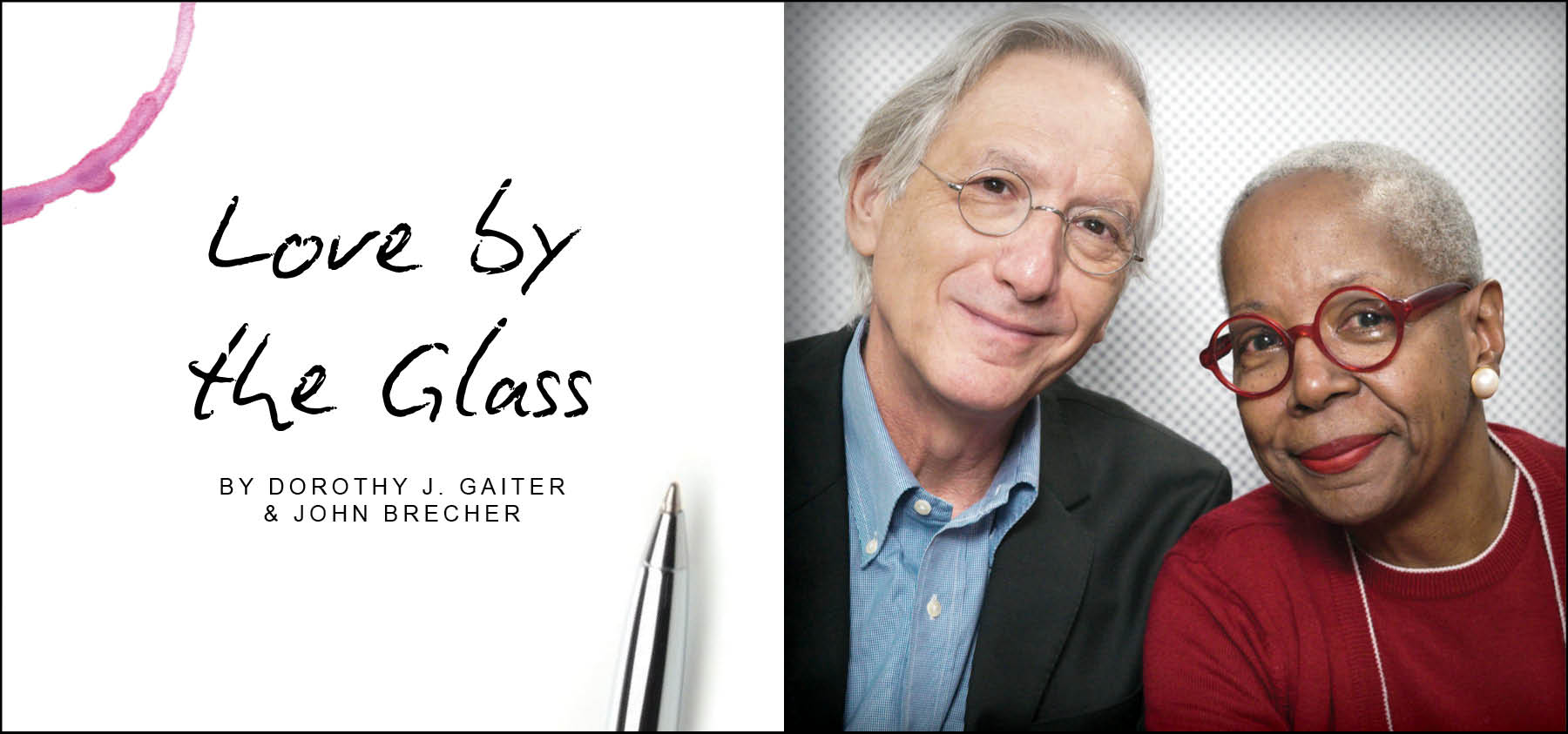

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective