What does a wine region, or country, do when it becomes best-known to consumers as a low-cost producer? Consider Chile, for example. We know that many consumers look for Chilean wine as reliable, inexpensive and thoughtful, and we do, too. But where does that leave wines that cost more because they are made in choice sites with the best care?

It’s a conundrum we have thought about for a long time – we wrote about the issue in relation to Australia back in 2005 -- and we have been pondering it anew because of a dinner we had recently with producers from a special area of Prosecco. We all know and love Prosecco, right? It’s ubiquitous, easy to drink and generally quite affordable. We think you should always have a bottle of bubbly in the refrigerator and Prosecco is a reliable choice.

Prosecco is primarily made from the Glera grape in the Veneto region of Italy and producers make somewhere between 600 million and 700 million bottles a year. That’s a lot of bubbly. Of that, just about 15% bears a special designation: Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore DOCG, named for the region’s two biggest communes, a region of undulating slopes. DOCG means it has to be from this area and its production needs to adhere to strict protocols. The label might have Conegliano or Valdobbiadene or both, and will certainly have DOCG. (Like so much labeling these days, this can get pretty deep. There is much more detail about this here.)

This special region in northeastern Italy between Venice and the Dolomites is a place with the right soil and climate for outstanding wines, which must be 85% Glera. It received DOCG status from Italy in 2009 and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019. Winemakers have been crafting these sparklers there for more than three centuries. While some of the wineries in the DOCG appellation are large – like Valdo, which is part of Bolla and produces about 10 million bottles of DOCG a year – others are small or cooperatives. Most undergo the second fermentation, that produces the bubbles, in tanks. The length of time in which the wines remain on their lees contributes to their rich variations.

The DOCG wines, in some cases, seem to us to have more personality than regular Prosecco, more of a sense of the place and the winemaker. For instance, we tasted Val d’Oca Brut “Rive di San Pietro di Barbozza” and it was lovely, with pure, focused citrusy tastes that would make it an excellent wine with dinner, especially seafood. It costs around $38 and while we’d say that is a good deal for a fine bubbly, our guess is that it’s a leap for consumers used to paying far less for a pleasant Prosecco.

At that wine dinner in New York, we met Diego Tomasi, the director of the consortium that represents more than 3,000 growers and producers in the DOCG. He spent most of his career as an academic, becoming an expert on the region, and was named director in 2021. We discussed with him how to get consumers to pay more for the DOCG when they are accustomed to lower-priced Prosecco. We followed up with some email questions. His answers have been condensed and edited for space.

GC: You have been an academic for many years, but gave that up to take this current role. Why did you do that?

Tomasi: After 30 years of work in the academic world, I felt the need to use the knowledge acquired in long years of study dedicated to the Appellation, which led to more than 200 publications. Among the most recent, the publication “Terroirs of Conegliano Valdobbiadene,” which was awarded by the OIV (Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin), is dedicated precisely to the soils of the DOCG.

Tomasi: After 30 years of work in the academic world, I felt the need to use the knowledge acquired in long years of study dedicated to the Appellation, which led to more than 200 publications. Among the most recent, the publication “Terroirs of Conegliano Valdobbiadene,” which was awarded by the OIV (Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin), is dedicated precisely to the soils of the DOCG.

(Diego Tomasi, photo credit Consorzio of Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore DOCG)

GC: There are more than 3,300 producers in the DOCG region and we'd guess most of them are quite independent. How do you manage to keep everyone going in the same direction?

Tomasi: All producers follow strict production rules that cover all stages of production, from the vineyard to the final product. Moreover, the Consortium, through periodic meetings and constant communication with producers, promotes and involves the production world in the path toward increasingly sustainable viticulture, gives indications with respect to vineyard and harvest management, as well as providing guidelines for communicating the distinctive elements of the Appellation.

GC: If we have this right, there were about 700 million bottles of Prosecco sold worldwide last year. Of that, about 100 million -- or about 15% -- was DOCG. Is that right?

Tomasi: Yes, that is correct. The Prosecco DOC, which represents a very large territory (spanning 2 regions and 9 provinces), recorded a production of 638 million bottles in 2022, while the Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Superiore DOCG, which covers a hilly area of only 15 municipalities, recorded the production of about 100 million bottles, in the same year.

GC: It’s obviously amazing to have been named a UNESCO site in 2019. But this must also come with some restrictions that make winemaking harder. Can you talk a little about this?

Tomasi: The benefits associated with UNESCO recognition are many. Our winemakers, prior to that, had understood the importance and value of landscape conservation, biodiversity protection, morphological integrity of the hillsides and vineyard architecture. Even before the UNESCO recognition, the producers had started to pay more attention to the products used for defending crops, to defend also the environment and increasingly developing the hospitality activity.

GC: We see that the total production area is 8,683 hectares (about 21,000 acres). Is that the limit of the acreage that can be planted?

GC: We see that the total production area is 8,683 hectares (about 21,000 acres). Is that the limit of the acreage that can be planted?

(John, Diego and Dottie)

Tomasi: Yes, in 2019 this was defined as the maximum surface for vineyards in our Appellation. In fact, we believe that this surface allows for a fair balance in the territory, between vineyard (30%), forest (57%), other crops (9%) and urban settlements (4%).

GC: Dottie thought you said that you are only permitted to make a certain number of bottles. Is that correct? And is that related to acreage?

Tomasi: Considering that the productive area has reached its maximum extension and that there are precise rules regarding yield, in the territory we can produce a maximum of 105 million bottles.

GC: Either way, how can winemakers/growers be prevented from overplanting or overharvesting since every grape is so precious?

Tomasi: At the regional level, there is a body in charge of controlling new plants. In addition, annually, each producer, by December 15, must submit a production declaration and this figure must correspond to the hectares owned and the respective yield, established by the production rules.

So there will always be a correlation between hectares and yields and grape production or number of bottles.

GC: Consumers think of Prosecco as a simple, easy-drinking wine that is inexpensive. But because of the unique nature of your wines, they are somewhat more expensive. How do you convince consumers that the extra money is worthwhile?

Tomasi: The fact of being produced in the hills, with low yields (max 135 q /ha) on the one hand triples the cost of wine production, because the slopes impose heroic viticulture, done by hand, with 600/800 hours of work per hectare annually. On the other hand, these lower yields and the particularly suitable hillside environment significantly raise the quality of our grapes and the wine produced from them. This is what we explain to the consumer to justify the higher price. Other elements of value that we communicate are the ancient production tradition, the Conegliano Valdobbiadene area being the historical area of Prosecco production, and the limited number of bottles produced.

Our advice: Some people reserve these DOCG sparklers for special occasions, as they do with their prestigious cousin, Champagne. But isn’t just being here enough? The next time you’re in a wine store or shopping online, give these special Proseccos a try. They’ll make every day better.

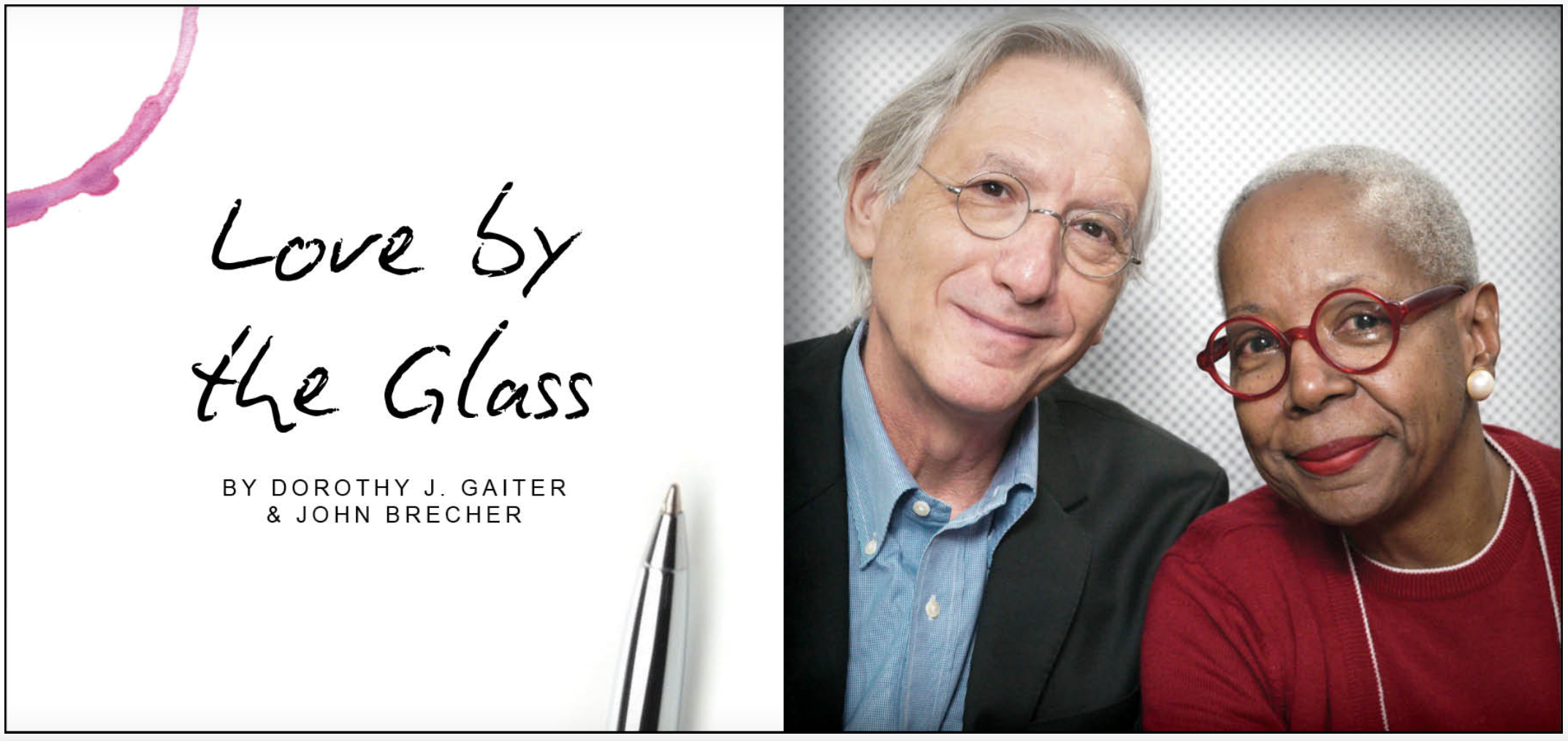

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett