We reached out to Randall Grahm the other day because we thought of him when we had a charming Bonny Doon Vin Gris de Cigare at a seafood restaurant in East Williamsburg. Though Grahm in 2019 sold his Bonny Doon Vineyard, which helped put Rhône varietals, fine wines with screwcaps and labels listing ingredients in Americans’ wine glasses, we had not tried his latest creations, wines from his experimental Popelouchum Estate in San Juan Bautista, Calif.

And with the efficiency of the Internet, in a few days we had, from the Popelouchum Estate Vineyard in San Benito County, his 2022 Estate Blanc, $65, around 200 cases made; the 2022 Cinsaut, the estate’s first harvest of this variety and air-dried for five days before crushing, $45, 20 cases made; and the 2021 Pinot Noir, $80, from “ultra-close spacing” of vines, 45 cases made. There was an evident vision that connected the three, which changed with every sip. All had high acid, with marked minerality. The Blanc, our favorite, had a white-tablecloth stature and some salinity. The Pinot was wet stones and tight at first. The Cinsaut, whole-cluster fermented, was nicely rich and held our interest throughout, not at all like some of the brooding, heavy Cinsaut we’ve encountered.

The Blanc’s back label contains the words, “Grrr, how frustrating!” The description on the website sheds some light on that. It’s 54% Grenache Blanc and 46% Grenache Gris but Grahm says he was too late getting the proper paperwork to the authorities to win approval to put Grenache Gris on the label.

Unflaggingly jocular now at 70, Grahm founded Bonny Doon in 1981 in a town called Bonny Doon in the Santa Cruz Mountains with the “foolish attempt to replicate Burgundy in California,” according to its website. With a course correction, his blend, Le Cigare Volant, a hat tip to the Southern Rhône’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape, became his flagship. He committed to the notion that GSM Rhône varietals -- Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvèdre -- as well as others would do well in California’s Central Coast. He became the avatar for a movement of like-minded, innovative winemakers, the Rhône Rangers, and dressed like the Lone Ranger for the cover of Wine Spectator in 1989.

Unflaggingly jocular now at 70, Grahm founded Bonny Doon in 1981 in a town called Bonny Doon in the Santa Cruz Mountains with the “foolish attempt to replicate Burgundy in California,” according to its website. With a course correction, his blend, Le Cigare Volant, a hat tip to the Southern Rhône’s Châteauneuf-du-Pape, became his flagship. He committed to the notion that GSM Rhône varietals -- Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvèdre -- as well as others would do well in California’s Central Coast. He became the avatar for a movement of like-minded, innovative winemakers, the Rhône Rangers, and dressed like the Lone Ranger for the cover of Wine Spectator in 1989.

(Randall Grahm)

In 1991, an asteroid was named after him, rhoneranger, fitting for a Peter Pan-like dreamer. In 2010, the Culinary Institute of America inducted him into its Vintners Hall of Fame. By 2004, he had grown Bonny Doon, with the addition of other brands and even distilled spirits, into the 28th largest winery in the U.S. But in time, with the industry consolidating and his admittedly wobbly business acumen, he concluded that his company was untenable financially. It was also too big and far from where his heart and searching mind had led him in the beginning: cultivating distinctive wines that express and amplify their unique terroir, wines that are Burgundian in their complexity and, with climate change, made from drought-resistant and disease-resistant vines.

So he sold off his brands, including his dear Bonny Doon, retaining a partnership and say in its production, and directed his attention in 2011 to his 415-acre property, Popelouchum, a word Ohlone Native Americans gave it that means “paradise.” There he is breeding grape varieties hoping to develop winning combinations that will not only make delicious wines but also employ environmentally sound agricultural methods for California’s climate in the future. He has planted 15 acres with varieties that include Ruchè,a dark-skinned, aromatic variety associated with Piedmont, and Sérine, a clone of Syrah that has been popular in Northern Rhône. He hopes to plant 65 more acres. He makes 450 to 500 cases total each year.

“How many wines do I think I’ll end up making? I don’t know yet but at the end it might be about 12 or 14 when all is said and doon,” he said, ever the punster. He is also partnering with Gallo’s Luxury Wine group to produce a range of Southern French-inspired wines from California’s Central Coast called The Language of Yes.

Grahm is a kind person and a talented winemaker who has sometimes tripped over his own sizable brain with its boundless wit. We have found it hard, sometimes, to get past his showmanship to appreciate his wines. Some of his stunts, like an elaborate funeral for corks, were in part intended to remove some of wine’s snobbish baggage and that’s certainly something we can get behind. Years ago, when we interviewed him, he told us, “I think that anything made out of true love has a greater likelihood of success than that which is done for other reasons.”

These responses have been condensed:

Grape Collective: You’ve said that 99 percent of the wines on the market are not wines of place. What’s so special about wines of place?

Grahm: They are more interesting, not just intellectually, but interesting emotionally, psychologically, more complex. There’s more there there to them. People kind of grope for language. I use the term dimensionality. There’s just more of this stereoscopic quality to the wines. There are hills and valleys, more movement in the wine. The wines are more dynamic when they have this thing that we call terroir or minerality or whatever it is. It changes how the wine is perceived. They have in them evolution. They have a beginning, a middle and an end. They evolve in the glass, which is quite interesting. It can drive people crazy sometimes. I’m sure you’ve tried a bottle of Burgundy and the last sip is often the best. And you think to yourself, “what was I thinking? I should have opened this the day before. Or two days before.”

Grahm: They are more interesting, not just intellectually, but interesting emotionally, psychologically, more complex. There’s more there there to them. People kind of grope for language. I use the term dimensionality. There’s just more of this stereoscopic quality to the wines. There are hills and valleys, more movement in the wine. The wines are more dynamic when they have this thing that we call terroir or minerality or whatever it is. It changes how the wine is perceived. They have in them evolution. They have a beginning, a middle and an end. They evolve in the glass, which is quite interesting. It can drive people crazy sometimes. I’m sure you’ve tried a bottle of Burgundy and the last sip is often the best. And you think to yourself, “what was I thinking? I should have opened this the day before. Or two days before.”

GC: We felt that way with your Pinot Noir. We finished it the day after opening it.

Grahm: Yes, it’s better the second day.

GC: The stated mission of Popelouchum is to...well, here is what the website says: “To propagate 10,000 new grape varieties, from disease-resistant progenitors, with the aim of a) identifying one or more new ‘genius’ grape varieties, and b) employing a radical new methodology for creating complexity in wine (the elucidation of terroir) by creating a highly diverse population in a vineyard (every variety being genetically distinct from the other).” So how is that going?

Grahm: Slowly. We didn’t get the germination last year that I hoped for. We’ve got more seeds this year at the nursery so hopefully they’ll do a better job. It’s coming along slowly.

GC: We just read your tweet that you were “making cuttings of Noire variants of self-crossed Sérine and now the nursery will graft 45 different variants for a field blend.” For one single wine, that kind of field blend?

Grahm: Yes, a single wine. I’ve already done this with the white Sérine using about 60 different variants. I just randomized it and gave them to the nursey which grafted them on 110R rootstock and planted them randomly in the vineyard. I’m replicating that with the red Sérine, with 40 or 50 variants to be grafted and planted next year.

GC: That sounds exciting.

Grahm: I’m running the experiment just out of curiosity. I’m planting an acre of proper Sérine and an acre or two of this mixed Sérine just to test the hypothesis: Does the mixed plantation produce a wine that is more interesting than the straight variety on its own? The theory is even though the offspring are less interesting than the parent, the parent being the most interesting, maybe something happens by virtue of just the extreme diversity that you’ve created. Maybe a tribe or a group of distinctive individuals, even though none are brilliant, there’s an intelligence in the group that could not be achieved another way.

GC: That’s head-banging stuff. We also read your tweet about your discovery that the plant you thought was Nebbiolo Rosé was just Nebbiolo.

GC: That’s head-banging stuff. We also read your tweet about your discovery that the plant you thought was Nebbiolo Rosé was just Nebbiolo.

(Dottie with Randall Grahm's wines)

Grahm: It’s a disappointment. But that’s life. There are some other possibilities. I have a woman friend in Baja who is looking for it so all is not lost, as yet. This is the second time, so I’m 0 for 2. What’s nerve-racking is that the U.S. Department of Agriculture did have Nebbiolo Rosé in its collection for a short time a number of years ago. So it stands to reason that it would be somewhere in California. I just haven’t been able to find it. I’m hoping that all this sums to something in the end and is not just an interesting excursion.

GC: Plans to dry farm only have also been scaled back. Some vines got two or three irrigations last year. And the Vitis berlandieri from Texas that you planted because it has drought-resistant rootstock and thrives in limestone-rich soil didn’t work out.

Grahm: It turns out that gophers really like Vitis berlandieri seedlings.

GC: What’s the most exciting discovery you’ve made at Popelouchum?

Grahm: Oh shoot. I don’t know. Maybe the realization that Grenache and Cinsaut, which are considered nice varieties, but kind of rustic, kind of country bumpkin varieties, I truly believe now that they both are capable of an elegance that I had not dreamt of. I don’t know if they will ever quite match a great Burgundy, because nothing can quite match a great Burgundy except a great Burgundy, but they can get awfully close and that’s quite exciting.

GC: What’s the most disappointing thing you’ve encountered?

Grahm: Well, there’s the rootstock. But I made a possibly really stupid boo-boo. I planted Furmint. I adore Furmint but I didn’t give it enough time to show what it could do and it wasn’t setting very well and I got impatient and grafted it (stupidly in parenthesis) to Petit Manseng and I’m not super thrilled with the Petit Manseng. It’s got a really weird virus, yellow blotch. So I may have to go back to Furmint.

GC: There’s something admirable about your ability to continue pursuing your dreams, no matter how difficult or long the shot. How do you right yourself after disappointment?

Grahm: You have no idea. It’s been a challenge. This has been a struggle, mostly a financial struggle. It’s not been easy, trying to persist. This is really meaningful work to me and I want to stay at it. I don’t want to give up. I never want to give up.

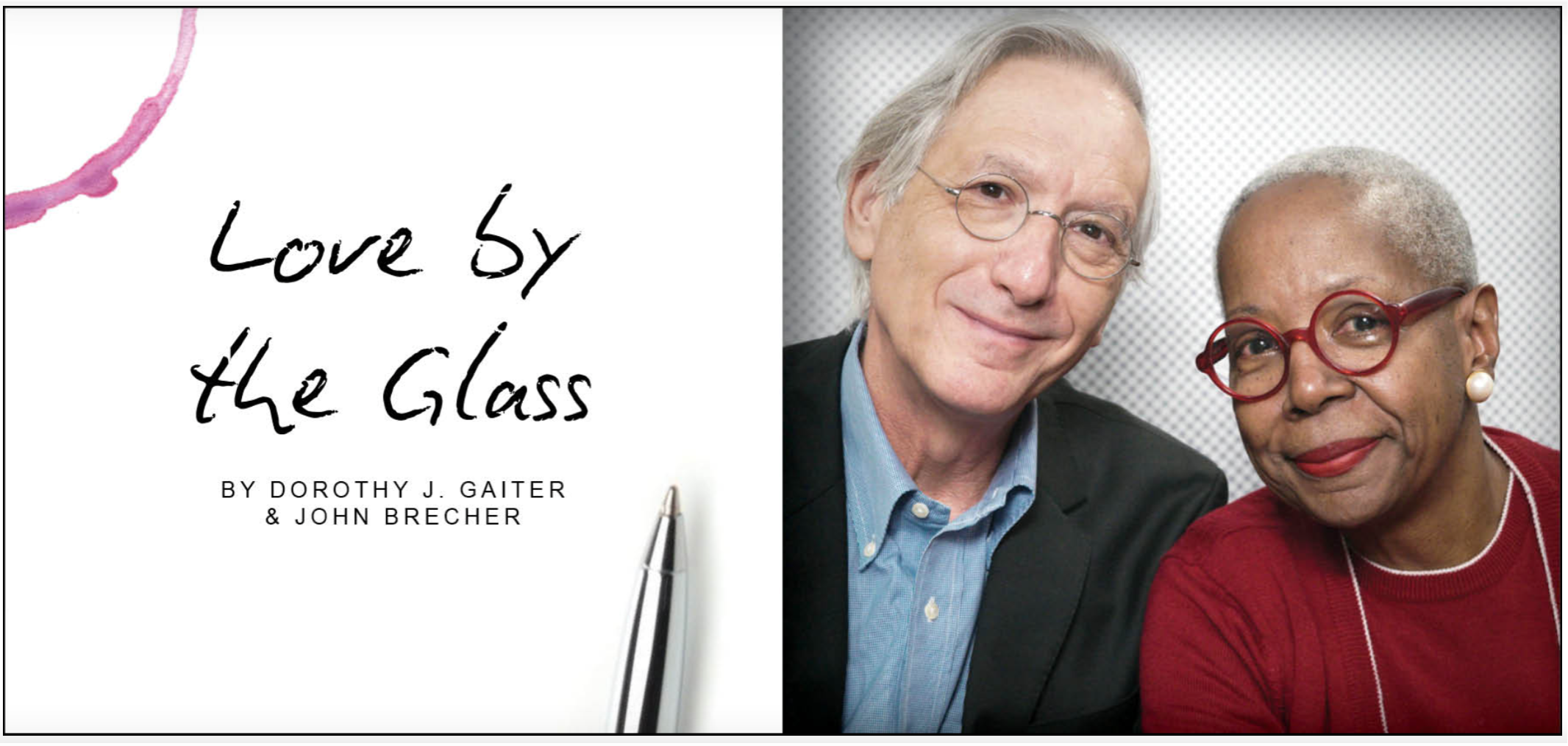

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett