Winemaker Iannis Paraskevopoulos yanks up his wetsuit, dons his buoyancy compensator, straps an air tank to his back, checks his regulator, adjusts his mask and slips into his fins. He’s ready to fetch his bottles of wine for a tasting. Diving equipment is now part of the tool kit for a growing number of winemakers around the world.

Winemaker Iannis Paraskevopoulos yanks up his wetsuit, dons his buoyancy compensator, straps an air tank to his back, checks his regulator, adjusts his mask and slips into his fins. He’s ready to fetch his bottles of wine for a tasting. Diving equipment is now part of the tool kit for a growing number of winemakers around the world.Yiannis slides off the transom of his speedboat and plunges into the cool waters of the Aegean Sea off the beautiful Greek island of Santorini. He dives 18 meters down into the bay to retrieve the 450 bottles of his 2009 Thalassitis dry white that he submerged in 2010 to see how the lack of light and oxygen and the consistent cool temperature affect wines made from the Assyrtiko grape variety. Thalassitis gets its name from the ancient practice of mixing wine with sea water (‘Thalassa’ in Greek) to add “therapeutic virtues to wine”.

Yiannis says, “The wines resulting from this process were called Thalassitis Oenos – sea-originated wine.”

Yiannis, who has a PhD in oenology from the University of Bordeaux II, knows things have moved on from ancient Greece and that, for one thing, it’s illegal to add sea water to wine these days. But the 80-year-old, low-yielding Assyrtiko vines in Episkopi, Akrotiri, and Pyrgos are close enough to the sea surrounding Santorini to be bathed in salty sea breezes most days. So why not go one stage further and see if sea-storage will add an extra dimension to the wine?

“The idea behind this experiment is to see how these amazing white wines age when totally deprived of any oxygen up-take," Yiannis tells me.

Four years after originally sinking them in a steel cage, they have vanished from the spot where he left them. He searches the seabed off the Kamari beach until his air runs short. He dives again... and again... and again until he eventually locates the steel cage 200 metres from its original position, shunted there by a terrific storm. When he opens the cage, 447 of the bottles are smashed to smithereens, their contents swallowed by the ocean. A Greek tragedy of sorts. Yet three bottles of Thalassitis have survived!

Above: One of the survivors!

And the verdict? Back in the winery’s tasting room, Yiannis sniffs deeply. It’s the distinctive and disgusting aroma of old fishing nets. Fortunately, he is just smelling the bottles. The wine? Yes, the grape variety’s distinctive minerality and delicate honeysuckle aromas are still there, but there is more. A smokiness. He tastes the wine. Bone-dry, as expected. Full-bodied, as usual. The great structure and crisp acidity are still there, too, but it’s not like any Assyrtiko he’s tasted before.

Despite the losses, Yiannis declares the experiment a success: “A success because after at least 10 dives we managed to locate the cage… A success because the wine – the one bottle that we opened – tasted awesome!

“Vibrant as a young Santorini but evolved at the same time," Yianinis explains. "Mineral, as a Santorini should be, but also complex and deep that kept evolving in our glass from a strange smokiness at the beginning to a floral profile after 15 minutes in our glass.”

He adds with a smile, “It’s a totally different wine to any other aged Santorini Assyrtiko.”

Every year since the 2009 vintage, Yiannis and his colleagues at Gaia Wines – agriculturist Leon Karatsalos and economist Christina Legaki – have been submerging a small portion of their annual 350,000-bottle output, so there are four more years under the sea. “Luckily, all other vintages are in place and looking fine, waiting to surface…” he says, sounding relieved. They aim is to rescue the 2010 in August 2015.

Gaia Wines is not alone in going to great depths to reach new heights in winemaking. I’ve also found winemakers in Italy, France, Spain, the USA, Australia, and South Africa who are submerging their wine underwater for aging.

Italian producer Bisson was one of the first to take advantage of the sea for cellaring, and has been consigning 6,500 bottles to the deep since 2009. Bisson’s Piero Lugano, a Cinque Terre wine merchant turned winemaker, chose the sea in the first place simply because he didn’t have enough room to store his new "methodo classico" sparkling wine. The wine, made from local grape varieties Vermentino and Bianchetti Genovese, is called Abyss as it is sunk to the bottom of the Bay of Silence (Baia del Silenzio), near Sestri Levante.

Above, Right: Piero raising the bottles, in more ways than one.

The wine, housed in a steel cage, stays there for 13-18 months. The next batch will go down sometime between late spring and summer, depending on the weather “since it involves a difficult, delicate and risky process,” says Piero.

Piero sums up the advantages of this technique: “It’s better than even the best underground cellar, especially for sparkling wine. The temperature is perfect (15°C), there’s no light, the water prevents even the slightest bit of air from getting in, and the constant pressure outside and inside the bottle keeps the bubbles bubbly. Also the movement exerted by heavy storms on the bottles is a sort of natural riddling.”

People who have tried it comment on the fine bubbles, crisp acidity, and complex saline and mineral flavours. It is sold in bottles covered in dried algae, seaweed and barnacles for about €60 (~$75 USD), well above the normal rate for an Italian sparkler.

California’s Mira Winery has been experimenting with aging red wine underwater, sinking 96 bottles of 2011 Cabernet Sauvignon into Charleston Harbor, on the east coast of the United States, in November 2013, and raising them this summer. It’s phase two of the winery’s "Aquoir experiment." In phase one, in spring 2013, 48 bottles of 2009 Cabernet Sauvignon were submerged in the same harbor for three months. When the wine was tasted it had “new depths”, according to winery owner Jim ‘Bear’ Dyke Jr, who lives in Charleston. But comparative chemical analysis in a lab in Napa found no differences between the wines.

The winemaker, Gustavo Gonzalez, explained the organoleptic differences: “I think the control wine, the one that was aged on land exclusively, just seems a lot tighter, whereas the one that’s been aged in the sea is just much more complex, broad, open and relaxed.”

The winemaker, Gustavo Gonzalez, explained the organoleptic differences: “I think the control wine, the one that was aged on land exclusively, just seems a lot tighter, whereas the one that’s been aged in the sea is just much more complex, broad, open and relaxed.”

Left: For many of these winemakers, this is a sign of complexity.

He attributes the differences to the rocking motion of the tides. “It’s not sitting still in a rack, but it’s almost comparative to Champagne, where somebody’s actually riddling it,” he said, pointing out that this was more effective with this wine as it had not been filtered.

Another big difference is the price: Mira’s regular 2009 Cabernet Sauvignon sells for $48 a bottle; the ocean-aged version went for $500 packaged with a regular one for comparison purposes. The first 12 "packages" sold within an hour of becoming available online.

This has led some critics to argue "underwater-aged wine" is simply a marketing tool. But Bordeaux producer Franck Labeyrie of Château du Coreau in Haux says he has 1,000 comparative tastings that prove wine tastes better after being down where it’s wetter (to coin a phrase from The Little Mermaid). He also argues that most winemakers do not pay enough attention to conserving and storing wine. In fact, he was so impressed with the results of experiments he conducted in 2012 that at Vinexpo in Bordeaux in 2013 he launched an underwater cellaring service for anyone who wants to pay €17 per bottle per year to submerge their wine in a trackable reinforced stainless steel box 150km offshore for ten years. With the help of marine maintenance company Jifmar Offshore Services, he has put two of these boxes on the seabed at a depth of 1,000m. One contains 600 bottles of Château du Coureau’s red and sweet wines and the other is available for part-hire.

For the past four years Franck has also been putting about 8,000 bottles of his Graves, a blend of Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc, in oyster baskets and submerging them 8m underwater in Arcachon Bay for six months. He sells three bottles of this Blanc des Cabanes for €45.

To protect his bottles from potential disaster, Spanish producer Luis Guillermo Pérez from Jerez de la Frontera encased 50 bottles of his 2010 red wine in individual amphorae and sunk them 12m underwater off the Atlantic coast near Conil in 2011. After a year, he brought the wine, a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah and Petit Verdot, up to the surface to taste them early last year. Pleased with the results, especially the more fruity aromas, and the “overwhelming” demand for the wine, the Andalucían winery has now sunk 500 more bottles of Garum undersea and has plans to age some Sherry this way too. Luis Guillermo Pérez is, after all, the son of Luis Pérez Rodríguez, a renowned expert on aging Sherry.

Below: One Luis Guillermo Pérez's successful bottles of Garum.

The Spanish are certainly taking underwater aging very seriously. An Underwater Drinks Aging Laboratory (LSEB) has been set up in northern Spain, off the Basque coast. The LSEB stores a wide variety of Spanish wine, including the local specialty txakolis (a slightly fizzy, high-acid, low-alcohol, minerally dry white wine made from Hondarrabi Zuri grapes).

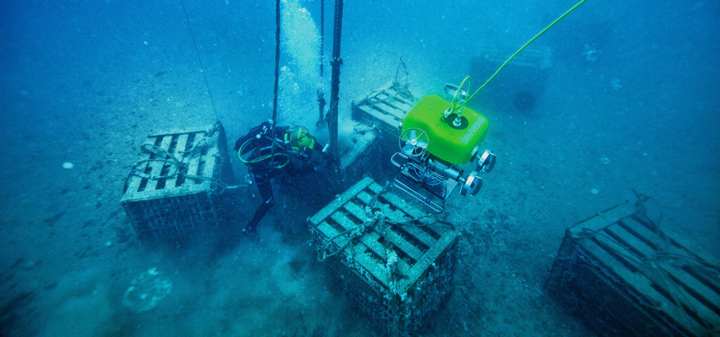

The company behind the lab, Bajoelagua Factory, started immersing wine from 27 Spanish producers in October 2009. Up to 1,600 bottles are kept 15-20m under the sea in the Bay of Biscay, off the white-sand beach at Plentzia (about 20km from Bilbao).

Right: LSEB prides itself on an impressive setup for an impressive vintage.

The underwater lab is equipped with sensors, cameras and an illumination system. The sensors gather data on the temperature of the water and sea currents and LSEB can control the level of light to assess its impact. In addition, monthly tastings are carried out to see how the wine is evolving. LSEB also offers wine lovers with diving experience the chance to visit the laboratory and the artificial reef which has been created around it (for €88 to €115 per person, depending on party size). Those without a diving license can go out to the area by boat and view the cellar and wildlife via the divers’ cameras. The trips conclude with a tasting.

Bajoelagua Factory is so impressed with the potential that it has launched its own wine brand, Crusoe Treasure. There are two Crusoe Treasure wines at the moment, Classic and Passion. Classic is a blend of Tempranillo, Mazuelo, and Graciano; Passion is pure Tempranillo. Both wines are aged in oak barrels (for a year/six months respectively) and then bottled. The bottles are stored with the fish for a year before being sold. Oenologist Antonio Tomás Palacios, who has been analysing the data from the undersea lab at his Excell Iberica laboratories, believes the underwater aging “leads to a perfect fusion between the fruit of the grapes and the oak."

Of course the wines don’t have to be cellared in the sea. Any body of water will do. One of the most interesting "aging wine underwater" experiments is being carried out in the sunken ruins of the Chartreuse de Vaucluse, a 12th century abbey in the Jura region of eastern France. 276 bottles of local wine were laid there by 12 divers in May 2008, 50 years after the abbey was deliberately flooded during the construction of a huge dam. The abbey is now 60 meters underwater.

The wine, a mixture of locally-produced white, red, yellow, straw and sparkling, is stored there – at a temperature of 4°C and at a pressure of seven bars. The plan is to raise 24 bottles every 20 years and to compare them with sister wines being aged more traditionally in cellars owned by the region’s largest wine producer, Domaine Henri Maire.

Henri Maire, who died in 2003 at the age of 86, was a bit of an eccentric and, I’m sure, he would have loved the idea of local specialty wines such as the yellow Sherry-like "vin jaune" and "vin de paille" (straw wine) being hidden in an eerie old monastery underwater. After all, he once walled in some bottles of vin jaune in the famous Paris restaurant, the Tour d'Argent, in 1955 with no plans to remove them until 2055. His wine company is also storing some of its vin jaune inside the Arctic Circle, at Spitsbergen, Norway, at temperatures of -40°C to see what that kind of extreme does to the wine.

And it doesn’t have to be bottles either. Well-known Bordeaux producer Château Larrivet Haut-Brion teamed up with respected barrel-maker Radoux to put an oak barrel into Arcachon Bay. Using a specially-made 56-liter barrel sheathed in a concrete chamber that allowed some seawater to flow in and out and for the barrel to rotate, they sank a 2009 Merlot-Cabernet blend for six months. It wasn’t submerged very deep and was partially exposed to air for about an hour a day during the lowest tides (about 25 to 30 times during the test period).

After the wine was tested in 2012 and compared to wine from an identical barrel that had been aged in the château's cellars, French wine expert Bernard Burtschy declared, “It was much better than it should have been.”

The barrel kept at the cellar in Leognan, named Tellus after the Roman goddess of the land, had a more youthful color and better polymerization of tannins but was rather disappointing. On the other hand, the barrel kept in the sea for six months, and called Neptune after the sea god, was more complex and intense, with softer tannins. Laboratory analysis showed the wine had lost some of its alcohol and gained some salt which Burtschy said brought out the best of the blend’s rich tannins.

All of the above methods are somewhat labour intensive and expensive as the bottles require the protection of wax seals, marine-grade steel mesh cages, and, ideally, GPS tracking devices — plus a boat and divers to put them in place and retrieve them. Bottles of still wine that go deeper also require the strength of Champagne bottles to withstand the pressure.

An Australian winemaker has cut these costs by simply filling a fermentation tank with water and popping French oak barrels filled with Shiraz in them for 14 months. Ninth-generation winemaker Ben Portet, whose ancestors started in Cognac, France, markets the wine as Ten Men Submerged Shiraz Pyrenees. He has recently released his 2012 version and his 2013 vintage is in the tanks now.

An Australian winemaker has cut these costs by simply filling a fermentation tank with water and popping French oak barrels filled with Shiraz in them for 14 months. Ninth-generation winemaker Ben Portet, whose ancestors started in Cognac, France, markets the wine as Ten Men Submerged Shiraz Pyrenees. He has recently released his 2012 version and his 2013 vintage is in the tanks now.

Right: Portet's investments were inspired by a shipwreck.

Ben told me he became interested in the idea after reading about the discovery of 79 bottles of Champagne in a shipwreck in the Baltic Sea off Finland. The wines were more than 180 years old and still drinkable… and highly sought-after. Eleven of them sold for a total of £90,000 in 2010, with a Veuve Clicquot from 1831 to 1841 going for €15,000.

Ben says you really can taste the difference between his submerged and dry-stored wines. “The submerged one is extremely fruit focused and has much more raw tannin compared to the normally-aged Shiraz. The traditional Shiraz is softer, rounder and more evolved as the wine is more complete.”

He is, in effect, using the lack of oxygen in the water to “hold the wine in time” so that it doesn’t age as quickly.

Ben was also inspired by a friend in South Africa. Craig Hawkins, winemaker at Lammershoek winery in Swartland, submerges 12 old barriques in concrete fermentation tanks filled with spring water for 11 months (until he needs the 8,000-liter tanks for fermenting the next vintage). The varieties that respond best for him are Grenache and Mourvedre. Craig told me, “I am really in love with this style of making wine and it has taught me a lot. I have always found the wines to be clean, free of bad bacteria and only a minimum of SO2 is required. The pHs are also lower than the other reds from the vintage so it’s got a lot going for it.”

Below: Hawkins of Lammershoek sinking into his wine.

His losses to evaporation are also minimal. Normally he has to top up his barrels every fortnight, but not those stored underwater. “I change the water every three weeks to keep it fresh and never top the barrels as they never need it,” he says. “I analysed the alcohol before and after the aging process and it stayed exactly the same, whereas above water the wines generally tend to increase slightly in alcohol due to evaporation of water etc. Another interesting thing is that the tannins of the underwater wines were very young and the wine definitely ages slower underwater as one would expect – whereas tannins above water tend to be more complete early on. The underwater wines have a sense of calmness to them however and are much more subtle in flavour.”

Craig also likes this method because he only has to use sulphur dioxide at the bottling stage. After 11 months underwater the Cellar Foot wine is bottled unrefined and unfiltered with a total SO2 of about 25 parts per million.

“I had a bottle of Underwater 2013 the other day, it had been open for 12 days – I didn’t know that – and it was still so alive and full of fruit,” he says.

I haven’t been able to get my hands on any of these wines yet, but I do think that knowing a bottle has been sleeping with the fish definitely does add something to it. It might be some flavor components; it might be lots of dollars; it might be the anticipation of that extra saltiness; or it may simply give you something extra to talk about as you sip and wonder what will winemakers think of next?