Next time you’re gulping a rosé, maybe when you’re into the second glass, stop for a second and ponder this question: Why don’t we take rosé more seriously?

We have tasted many rosés recently and have conducted broad blind tastings as far back as 1998. These days, we find them overwhelmingly to be sweet and false, more like they were made in a lab than in a vineyard. Our tasting notes about one the other night says “bubble gum.”

Our bar for a good rosé is simple: It should taste like fruit, have balanced acidity and, generally, be dry. We’ve recently had some that hit the spot for us. One was Anaba Wines Rosé of Grenache from Sonoma, which was filled with life. Another was Fiddlehead Cellars “Pink Fiddle” Rosé of Pinot Noir from Sta. Rita Hills, which sang of – guess what? – Pinot Noir.

Our bar for a good rosé is simple: It should taste like fruit, have balanced acidity and, generally, be dry. We’ve recently had some that hit the spot for us. One was Anaba Wines Rosé of Grenache from Sonoma, which was filled with life. Another was Fiddlehead Cellars “Pink Fiddle” Rosé of Pinot Noir from Sta. Rita Hills, which sang of – guess what? – Pinot Noir.

And then there was one that was so good that it took us into the heart of the meaning of rosé.

In the world of rosé, there’s a heated debate about how it’s made. Some rosés are created with the saignée method, in which juice is bled off in the process of making red wines. This concentrates the red, but it means the rosé is more of a byproduct – and, of course, some of these can be good.

The other way is “intentional,” a word to look for on a label or a tech sheet. These rosés were always meant to be rosé, so the vineyard is chosen for that, the grapes are picked with that kind of acidity in mind and the winemaker’s vision is clear.

Interestingly – and we did not know this when we first tasted them – both the Anaba and Fiddlehead are intentional, and proud of it. Anaba winemaker Katy Wilson, in her spec sheet, writes: “An intentional rosé, this wine is aged three months on lees with low intervention and low sulfur.” Fiddlehead winemaker Kathy Joseph writes of hers: “Our rosé is so much more than simple ‘bleed’ juice and deliberately not a saignée. Rather, this wine benefits from the whole grape character which is picked specifically to become this wine and this wine, only.”

All of which brings us to OTO, an intentional rosé with an unintentional background undergirded by faith. OTO stands for “One Time Only” and 50 cases of it were made by Chris Howell, wine-grower and co-general manager of Cain Vineyard and Winery in Napa, best known for its Cain Five. Chris and his wife and co-general manager, Katie Lazar, the director of sales and marketing, are among our favorite couples. We have known them for years and we are regular customers. After we saw them in April in Napa, they sent us two bottles of OTO 2021 Rosé of Tempranillo with a warning that, because the wine was minimally processed — no malolactic fermentation or filtration --it would be cloudy.

We opened the first for Mother’s Day and it made us stop in our tracks. We noted rhubarb, herbs, kumquat and strawberries that still had perfect acidity (Dottie knows her strawberries). Totally dry, this was as serious a wine as any notable, fine, white or red we’ve had in a while. By serious, we mean especially worthy of contemplation, expressing profundity.

It is also the only rosé Howell has made in his 32 years at Cain. He hasn’t even made a white in about two decades and he and Lazar rarely drink rosés, which they too often find “thin and insipid” and not good with food, they told us when we called to talk about how their OTO rosé came to be. It’s the third OTO in the winery’s history, it turns out.

“Back in 2020 we were all staring at each other and going what now?” said Lazar, who came up with the idea of OTO. “We were at the beginning of COVID and we weren’t seeing people. It really is about keeping connected with people. This is a positive way of sharing stuff and involving them while looking through a different glass at Cain.”

So they bottled two wines that were not going into their famous blends, Cain Five and Cain Cuvée, as their first OTO wines, a 2018 Merlot and a 2019 Cabernet. “We offered them to our customers to give them a view into what we see, the way the wines start and evolve and they were so beautiful at that moment,” Lazar said.

Then in late September 2020, Cain was devastated in the Glass Fire. Its vineyards, winery and historic barn on Spring Mountain were destroyed and Howell and Lazar’s home, along with those of other long-time employees, were lost. The loss of the vines gave them an opportunity to think about the future in a different way, especially with the reality of global warming.

“In looking at the future, are you going to try to plant the same varieties or should you be considering other varieties? Should we at least begin to prepare for it? One that interests us is Tempranillo,” the great grape of Rioja, Howell told us. They found a vineyard they liked in the Sierra Foothills – Shake Ridge Vineyard – and signed a contract in 2021 for a few tons, “just a drop of it.”

“And then came the wildfires to Amador County and these vineyards are swimming in smoke,” Howell said. Recalling that some big wineries have bailed on contracts to grapegrowers because of smoke, Howell said, “The last thing we’d say is no we’re not buying it,” adding, “we’re going to vinify it and see what the outcome will be.”

So they rushed to get the grapes picked for a rosé. “Hedging our bets, we said we’ll take a piece of this Tempranillo and press it off immediately with far less exposure to the skins and thus potentially less of the molecules associated with smoke taint,” Howell said. They made some red Tempranillo but ultimately didn't like it.

We asked Howell and Lazar together to recreate for us their discussion about making Cain’s first rosé and they sounded, well, like a married couple.

We asked Howell and Lazar together to recreate for us their discussion about making Cain’s first rosé and they sounded, well, like a married couple.

(Photo: Katie and Chris with OTO Rosé)

Lazar: “It never occurred to me that Chris didn’t know what to do. I didn’t think twice about it.” Her faith in the mission and how the wine would be accepted was strong.

Howell: “That’s really interesting to hear you say it like that, because when I think about it now I realize my reaction was, well, this rosé is interesting to me personally because of my opinions and what we’ve experienced with domestic rosés but the truth is we have no credibility at Cain with anything like this and I’m not really even interested in distracting people with such a complete detour relative to what we’ve been doing. So I thought we’ll make it and ultimately decide what to do with it.

“I probably said you can do it but I don’t know that we want to sell it.”

Lazar: “I think people sometimes learn more from reflection and refraction than they do sometimes by the straight ahead and by only making the same things all the time. This gave us a chance to give people that reflection and refraction and a learning experience.

“Our life is about looking forward and accepting change. My favorite term is making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear and that’s our life today. And I just go like, why not? We have customers out there who are accepting of our desire and willingness to be experimental and so immensely, immensely supportive. We have that love to rely upon. I just accept that love. I didn’t think twice about it.”

They picked the grapes at 6 a.m. and the harvest arrived at the winery by noon. Working with winemaker Mandy Donovan, “the wine was fermented in the barrel and bottled straight off the yeast lees,” Howell said. “You’re getting everything.”

We saved the second bottle and just opened it, after speaking with Lazar and Howell.

Our notes: “The wine in the clear bottle looks a little like honey, as if it’s viscous, with floating stardust in it. We’ve never seen anything quite like that. We poured it off the cloudiness because we thought it would be fun to have it half and half. It looks and smells like orange wine. Kumquats and tangerines. Great acidity. Real gravitas here. Herbal and savory. This would be an incredible pair with really fine dining. The finish is endless and filled with citrus, minerals and that hint of honey. And yet it’s so very dry, with significant tannins – a world of contradictions. Roasted almonds. This is a wine of real substance, yet at the end, we are drinking clouds.”

Our notes: “The wine in the clear bottle looks a little like honey, as if it’s viscous, with floating stardust in it. We’ve never seen anything quite like that. We poured it off the cloudiness because we thought it would be fun to have it half and half. It looks and smells like orange wine. Kumquats and tangerines. Great acidity. Real gravitas here. Herbal and savory. This would be an incredible pair with really fine dining. The finish is endless and filled with citrus, minerals and that hint of honey. And yet it’s so very dry, with significant tannins – a world of contradictions. Roasted almonds. This is a wine of real substance, yet at the end, we are drinking clouds.”

Let’s circle back to the question about rosé. Which came first: Did rosé – even so many from Provence – become simple and sweet, so consumers stopped taking it seriously? Or did consumers expect a sweet and simple pink product (perhaps White Zinfandel had a role) that was also inexpensive, so it became economically difficult to charge enough for a thoughtful, well-made rosé?

Here’s the bottom line, dollar-wise: The OTO cost $33. The Anaba is $34 and the Fiddlehead is $30. Our advice would be to tell your trusted wine merchant that you are willing to pay that kind of money for a rosé that will change your mind about today’s rosé and see what happens. At a time when some California Sauvignon Blancs are selling for more than $75 — quite a bit more -- perhaps rosé is the next frontier.

For their part, Howell and Lazar have been changed by their own rosé. They’ve become fans of Tablas Creek Winery’s Patelin de Tablas, for instance, and they’ve often enjoyed the famous Tempier Bandol Rosé from Provence. But the question of rosé not being taken seriously intrigues them as well. “We don’t take it as seriously as we should,” Howell said. “We don’t see rosé in the same light as even white wine. Why isn’t rosé taken at least as seriously as white wine?”

Lazar added: “Maybe rosé will come back to its roots. It reminds me of the comments people are making about fast clothes today -- the throwaway world. So antithetical to what we need to be doing. I feel like rosé is going through its fast clothes segment. It was something real and then it became popular and it got Kim Kardashianized. And it needs to come back and it will come back as people get tired of that.”

Here’s hoping.

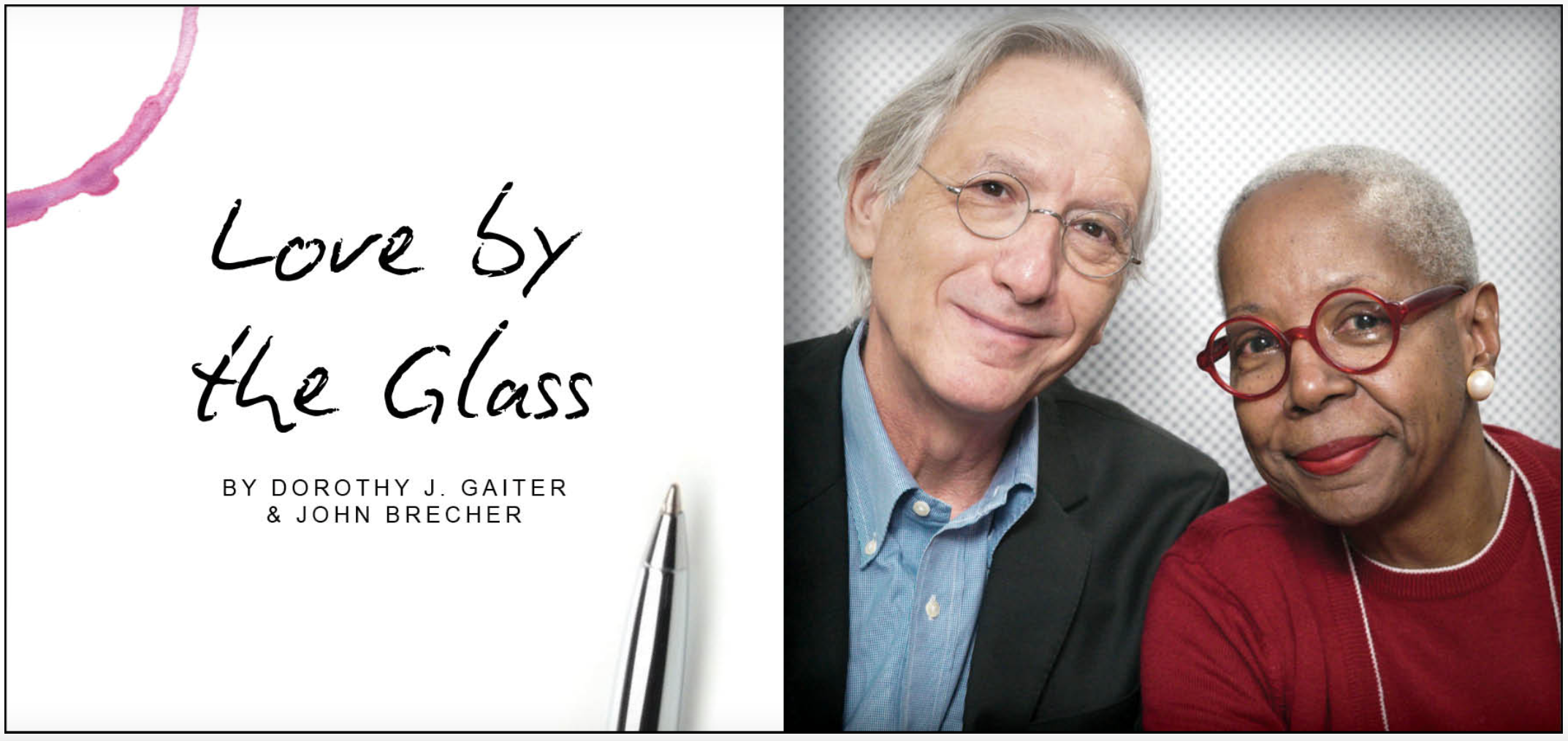

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett