Steve Matthiasson is a California winemaker and viticulturalist who is also a leading player in a movement described by wine writer Jon Bonné as "New California." In Jon Bonné's book of that name, Matthiasson features prominently (below left). The "New California" approach to winemaking centers around the idea of "balance." The "New California" producers share an Old World European sensibility in their approach, which focuses on reflecting place while at the same time demonstrates restraint and nuance. The movement is also in part a reaction to increasingly big, high-alcohol, extracted Napa Cabernets that had attracted impressive critical scores and steeper price tags.

A proponent of a balance in wine Matthiasson was one of the main protagonists in a 2015 New York Times piece called Wrath of Grapes which pitted traditional winemaking with a new generation focused on making "balanced" lower alcohol wines. According to author Bruce Schoenfeld his wines seemed "out of place in Napa."

A proponent of a balance in wine Matthiasson was one of the main protagonists in a 2015 New York Times piece called Wrath of Grapes which pitted traditional winemaking with a new generation focused on making "balanced" lower alcohol wines. According to author Bruce Schoenfeld his wines seemed "out of place in Napa."

But aside from philosophy, what is most important about Matthiasson is that his wines are tasty and interesting. Matthiasson works with Cabernet Sauvignon but also with less expected grapes such as Ribolla Gialla, Tocai Friulano, Semillon, Refosco and Cabernet Franc.

In addition to his winemaking Matthiasson is a viticultural consultant to some of Napa's top wineries including Stag's Leap Wine Cellars, Araujo Estate, Spottswoode and Hall. In Bonne's The New California Wine, Matthiasson is described as "the thinking man's viticulturalist." He espouses an organic philosophy and a way of approaching the grapes that allows for a lower-alcohol, less-extracted wine.

Grape Collective talks to Matthiasson about balance, organics and philosophical wine movements.

So Steve, when you were younger, did you always know you were going to be a winemaker?

I didn't even know what a winemaker was when I was younger.

How did you get from not knowing how, what a winemaker was, to becoming a winemaker?

That's a good question. What I didn't know was what a winemaker was, but I did know that I loved food, I loved growing things, gardening. I loved being on farms. I loved beer and wine and things like that as soon as I was a teenager. So I didn't know what a winemaker was, but I knew that those were my interests and my passions and somehow, you know, if I just sort of got lucky in the sense of following those one step after the other, and I was able to find myself, you know, a winemaker, because that is the profession that combines all that stuff.

You started out as a consultant. What's the job of a consultant like? I mean, you're working for other people, you're helping them with their grapes. How would you describe it?

Well, I mean, I hate that word, "consultant," but I guess it's true in the sense that you're consulting.

It sounds like the guy that screwed up the Oscars, right?

Yes, someone coming in with a clipboard. You know, grape growing is ultra-complex, right? Because not only is the science of viticulture extremely complex, but the people who own the vineyards have to deal with the business as well, and the business of growing grapes is very complex. Labor, equipment, selling, you know, dealing with the finances. That's a whole thing in and of itself. So with farmers, in general, in California at least, I assume it's like that in other parts of the country. I'm not positive about that. In California, the crops are so complicated that it's very normal and traditional for farmers to have someone that comes around and checks their crop and makes sure everything's good with the crop. Checks for bugs, nutrients, things like that.

They're busy trying to just kind of keep the whole thing going, and so having help dealing with the technical side of their crops is common. Especially when someone has maybe been a conventional farmer and wants to go organic, well, how do you do that? I got past what I'm going to do. You know, organically, now, I'm used to spraying, so you need to have someone who's checking on them and making sure that everything's okay, giving you advice on how to deal with this, that, or the other problem organically.

So it's a lot of walking the properties and checking on things, and then saying okay, here's what I saw, here's where we're at, you know, and then collaborating with them on coming up with a plan. So it's straightforward in that.

Now, it's evolved for me. A lot of what I do now is kind of high-level strategy with clients. I'm not doing as much of the hands-on work I used to do because I'm busy with our own stuff, but I enjoy the high-level strategy, so it's, you know, meeting with Dalla Valle, for example. We get together once a month, we walk through all the vineyards. The viticulturist there has a list of questions. She asks me all the questions. They're concerned about this area, that area. These vines look a little sick or these look a little dry or you know, these are a little too big a risk. We decide yeah, they are a little dry, here's what we should do about it.

Maybe I'll make some suggestions, or they make some suggestions. I'd say good idea, but they're looking to make sure, you know, they don't want to make a mistake and it's nice to have a second opinion. Then after a couple hours, you've walked through the whole place, there's a game plan. Come back next trip, by then, there's a new set of questions, new set of issues, we're that much further in the season, etc.

The Linda Vista Vineyards in the West Knoll area of the Napa Valley is around the corner from the Matthiasson house

In terms of Napa, it's a monoculture, right? I mean, it's grapes.

Basically, yes. We have our two fruit orchards. My wife in her years working for food policy and she was like this is a farming community and there's nothing to eat, so we planted the two orchards to sell at the farmer's market, but that's minuscule.

One of the challenges with monocultures is that a pest can come or there's a disease.

Right.

That can then just sort of blow through and really cause a lot of problems.

Right. There's a bunch of problems..

How do you deal with these sort of catastrophic potential issues that can, you know, wipe out somebody if they lose their grapes, right? I mean, that's people's livelihoods.

Yes. And it's the economy of the whole county. Because it's the economy of the whole country, there is constant vigilance. So the agricultural commissioner is an office, it's a governmental office, and they have staff that their entire job responsibility is monitoring for invasive pests. When I was driving to the airport, I got a call, you know, "Oh, we want to hang our trap for vine mealybug," which is one of the pests that moved in, and they hang traps all over the place. And they were calling, "It's a new season of trapping, we need the gate combo for your Linda Vista Vineyard so she can go hang the trap." So these are people work for the county that are trapping for insects.

You have the growers, we communicate. You know, you have task forces. It's just constant meetings and vigilance and working together, information sharing as to what's going on, because since it is such a vulnerable monoculture, if that person over there all of a sudden has a brand new pest, everyone else around there is justifiably, you know, concerned. So there are group resources to help that person deal with it and nip it in the bud, and we'll enact monitoring all around it and just kind of snuff it out.

So I would imagine, I don't know how it works in places like Burgundy or Bordeaux, these other kinds of monocultures, or monoculture areas, but I would assume it's similar, but you know, with grape growing, you're not, these regions, grape growing lends itself to monoculture, because there are only these little pockets that do grapes well, and so you can't just rotate your grape crop or spread it out the way you do a lot of other crops, because grapes are so site-specific and so tuned into a certain spot. So you have to band together and work as a community.

So like in my case, our wines are very different than so many of my colleagues and neighbors in Napa, but I'm very much part of that community and we all work together on all of this stuff. You know, you have to.

(Steve Matthiasson with Jake Bilbro of Limerick Lane winery)

Being somebody whose focus is organics, has that become more challenging when you deal with some of these pest issues?

Absolutely. A few things, I think, maybe work a little bit better with organics, like the vines, I think, can handle phylloxera, for example, a little bit better under organic soil management, but in general, if you can't just spray the insecticide, then you have one hand tied behind your back. So you have to be that much more diligent and proactive for sure.

So being a grower is oftentimes a very different activity and job from being a winemaker, and many people are happy just being a winemaker or happy just being a grower. What made you make the transition from just growing to growing and winemaking?

Well, I've always loved the alchemy, the magic of transformation, of fermentation. You know, I brewed beer in college, and I still am just blown away by the magic of that, right? So I brewed beer in college, then when I started working, I went to grad school at Davis and I started to get grapes from the student vineyards and started making, you know, home wine. Then when I started working at Modesto for four seasons consulting, I would get grapes. So I always made home wine every single year.

When I met my wife, we'd do it together and it was a really fun activity. Part of the rhythm of our year was making our batch of wine. Bring your friends over, it's just a lot of fun, and so I did that. Really for almost 10 years of working in vineyards, and a few things.

Partly, the style of wine changed from the late '90s into the 2000s, where it got very ripe. A lot of consternation in the grape world, the grape-growing world at how ripe everyone was picking and feeling like the winemakers are picking and it's turning into raisins and we're losing our production and what's the point of good viticulture, raisins all taste like raisins, and there were a lot of meetings, and what are we going to do about this new thing of long hang time, and it was not that long ago. It was just 15-20 years ago, and really 15 years ago was when it really came to a head.

So there was that, and there was also just as a craftsperson and control and just thinking, you know, I'm starting to feel like I'm starting to understand viticulture, and but it feels very incomplete. Like we're not taking it all the way. You know, because you're making wine in the vineyards. That's, you know, when we say we're making wine in the vineyard, we really are making it there. I think of springtime as when we're making the wine. Because you know, the timing of cultivation, the managed amount of water the vines are getting, timing of thinning the shoots to encourage either vigor or depress vigor, you know, fruit thinning, pruning for nice spacing, you know, adjusting the leaf cover over the fruit so that it gets a little bit of speckled light, but not too much depending on the row orientation and what you're trying.

You know, these were all things where we're making the wine. You know, major impact on wine quality and style. Much more so than can take place in the cellar, really. Then someone else decides when to pick it and does all the winemaking. So it's sort of like I started getting so that I wasn't happy at harvest because originally, I was just trying to learn the craft of viticulture and I was lucky if I got to harvest, now it's your problem. But it kind of evolved to where okay, I think I got this, and I'd like to take it the whole way.

Steve and Jill Klein Matthiasson

That coupled with what was going on in the world of wine with longer hang time and stuff, and my wife is, you know, she planted the orchards. Well I planted the orchards, but she told me to. She's really into selling at the farmers market. She worked for 10 years with non-profit community alliance with family farmers that was about local foods. This was in the '90s, you know, so they'd have seminars for farmers. How do you sell directly to chefs?

So hugely, you know, Alice Waters is just like, you know, a pope in our family. Local produce, this idea that the world would be a better place if we were eating as a family fresh produce and we want our wine to, our wine to exist in that vein, right? We think of our wine as fresh, local produce, and we think of it as something that's healthy and something that brings people together around the table, and that is in the same vein as something like a perfect carrot that was grown carefully by a farmer. You don't want to screw it up. You do simple preparation to so that you can taste that carrot.

That's the mentality, and so you know, long hang time, heavy wines with lots of oak that's the wine equivalent of like heavy sauce and heavy technique in the kitchen as opposed to, you know, transparent technique due to carefully sourced produce.

So all those things. So that was our ethic, and then in that point in my career, it's like we had two little kids and let's start a family business, and so all of those things folded together. My wife has always run the business because then she works out of the house running the business. So all those things kind of caused us, in 2003, to like go for it commercially.

And when you decided to get into winemaking and you realized you were going to launch this business, I mean, all of the other parts that are not just the technical parts but the sales, the marketing, you know, having to do market visits.

Oh, yeah.

The labels, the buying stuff, you know, all of that. Did you know what you were getting into?

The labels, the buying stuff, you know, all of that. Did you know what you were getting into?

Hell no.

We had no, we were so naïve, it was ridiculous. Just pathetic. And so, you know, I mean we had some connections. You know, I worked in through all the wineries I worked for and stuff, so we got a few connections with some people to talk to. My wife, Jill, had some connections with some restaurants in San Francisco through the local food world. So we could kind of get started selling stuff. We didn't know how any of that worked. We had no clue.

It's been a non-stop learning curve. Learning how to sell wine. Learning how distribution works. Learning how business works. You know, accounting, taxes, all that kind of stuff. We didn't know any of that stuff. We went through some huge speed bumps of where if we'd have known how to do that, we could have saved ourselves so much pain, but you know, that's been ...

It's part of being an entrepreneur, right?

Exactly.

You know.

You've probably gone through the same thing.

Of course.

You can see why the serial entrepreneurs sell the business and then go okay, I'm going to start over again knowing what I know, but the funny thing is rarely does it work the second time, because part of it is like having kids. You just have to rise to the occasion. You don't know what you're getting into, and that's part of it.

Always new problems.

You just, but you got to do it.

Always new problems. Always different problems.

(The Michael Mara Vineyard is west of the town of Sonoma, at the base of the Sonoma Mountain range)

There was an article in the New York Times a while back called Grapes of Wrath. And it pitted these two forces in the California wine world. The big blockbuster Napa wines with the high alcohol, the big fruit, with these sort of new winemakers, of which you were included, who are focused on balance, who are focused on lower alcohol, who are focused on higher acidity.

Right.

Is that a fair statement of these two camps existing?

Yes. I think that the bigger blockbuster camp would take exception to the less blockbuster camp, they say, calling the wine balanced because they're like, "Well, our wine's balanced." Like you know, "You're saying we're not balanced?" And I get that, but you know, I don't know how to reconcile that so much. But for sure it doesn't need to be pitted into this like us versus them thing, though.

We have this problem, which is this problem was that the wine conversation became dominated by this, I'm going to say mythology, that the warm climate of certain New World growing regions, whether it be California or Australia or Argentina or Chile, dictated a level of ripeness, and that's just not true. So the problem was that if you were in one of those regions and you don't choose to make a wine in that style, of that high level of ripeness, you can't sell your wine, because there's no box into which your wine can go.

That your wine doesn't exist because you're not from Europe, you're from California but your wine tastes like it's from Europe, so therefore it doesn't fit in a box, I can't sell it because it doesn't make any sense. It's inconsistent with what we know to be true about California. So go home.

I mean, I had a sommelier tell me, "If I want fake Europe, I'll drink real Europe."

Wow.

To my face told me that.

Wow.

And this is 10 years ago.

In New York?

In New York, yes.

Do you still see that person?

No. That was the most direct of what I got a lot, though. So it was sort of like, and a lot of my sort of colleagues in California trying to do similar things to what we were trying to do, just make our wine we wanted to make, which happened to be higher in acid, lower in alcohol, lower in ripeness had the same problem. In pursuit of balance. So in that article with Raj Parr, In Pursuit of Balance was formed to create a space in the world of wine for people who share that particular philosophy to survive and exist. It was never created to try to keep anyone else from making the wines they want to do, but we were told we can't make our wines like that. You know, so that was the problem.

I mean, now, we've successfully, I feel, changed the conversation, so there is space in which we can operate. So it's sort of like mission accomplished. We can exist. We're a legitimate form of California wine. So now it just comes to is the wine any good? Does the market want this bottle? But not that this bottle doesn't have a right to exist, because that's not representative of California. It's more just is it any good, is it the right price. The stuff a normal wine has to deal with in the marketplace. That's all we ever wanted was just ability to legitimately have our wine be part of the marketplace for better or for worse, and I think we're there.

The Red Hen Merlot Vineyard sits along Dry Creek at the base of Mt. Veeder in the Oak Knoll district

You use varieties in your wines that are not common in California. Why did you make that decision?

So why we decided to use different varieties. So when I was a kid, my mom grew African violets. I'm going to give this funny little side story, but there's the African violet society, they compete on their African violets, and you would be amazed at how many different African violets there are. There's not just the regular old violet-colored ones, but there's ruffled ones, there's one with double petals, there's red ones, striped ones, and so anyone who grows African violets doesn't want, you know, they have a whole collection of African violets, of different African violets.

Same thing if you grow roses. You've got a collection of roses. No one who's into roses grows one red rose. Everyone knows someone who's into roses, whether it's their grandma or somebody down the street or whatever, and there's a whole collection of different roses. If you're into horticulture, that's what you do.

I love horticulture, and so I like exploring. I just geek out. I just love trying different varieties, seeing how they grow. You know, it's just fun just to get your hands on another variety. You get it in the ground, look at it, learn how it grows. They all grow a little differently. They all require a little different tending. How do you make wine out of them all? You know, how does the wine turn out in our climate in Napa? Very differently than it is always from where they're from, somewhere in Europe.

Like Cabernet, we know how Cabernet does in Napa. Turns out it does really well in Napa. I mean, it's kind of taken over in Napa because it does so well there. Got that. So with Cabernet, the exploration is how do you do it well. It's the exercising of your craftsmanship with Cabernet.

Schiopettino, it's very different. No one knows what Schiopettino even tastes like practically from Italy let alone from Napa, so then Schiopettino, it's like that pressure is off, and instead, it's the fun and joy of let's plant a brand new variety that's never been here before and kind of see how it grows and see what the wine tastes like, and you know, it's going to be good. If you don't screw it up and you do a good job, it'll be good, but we don't know what it's going to be like.

The wine is like the flower, the rose. You grow the bush all year, it's going to get some more black spots, some less, this one's leggy, but then you get to see the flower. With grapes, the wine is our flower, basically.

(Their Pinot Noir Vineyard in Carneros, on the windy/foggy edge of San Pablo Bay; the horizon line is the cold wetlands)

Was there one variety that you put in the ground that was questionable about whether or not it would do well? Then you were like this is amazing, I'm so excited about this.

That would be Schiopettino, actually. Schiopettino because we didn't know, had never even had a Schiopettino. The synonym is Ribolla Nero, and so I saw, oh, well we have Ribolla Gialla, we better do Ribolla Nero, because, you know, get the whole. Then we didn't realize that that is just, that synonym is not correct and it has nothing to do with Ribolla Gialla, and after we saw it growing. It's really hard to grow. It gets shatter, really bad shatter, and it has this physiological problem where the shoots die and break off, but the wine's amazing, and so that was really cool. Really cool to see.

Each of the varieties, though, like Cabernet Franc, you know, the Cabernet Franc, I was trying to do an experiment and pick it early, thinking okay, maybe the chocolateness is more related to pyrazines and I'll pick it early and we might get more chocolate, and at that stage in my winemaking career, I was more familiar with Bordeaux than I was with Loire by a long shot. Not that I was that familiar with Bordeaux, but very unfamiliar with Loire.

So then I taste it, it was like ah, this tastes terrible. It's like weed-whacking the side of the road, it's so herbaceous and sappy and put the barrel in the back and forget about it. Year later, tasting it with Eric Asimov in the cellar, this was like 2009 or something like that, and I'm like, "Hey, you want to try this Cab Franc," thinking to myself I'm going to tell him how this was a failed experiment. It'd be interesting for him.

He's like, "This is fantastic." Like what? And I tasted it, I was like holy crap, it's completely transformed over the last twelve months. It's really good. Kind of sage, lavender, you know, and all that herbaceousness. I learned, a lot more comfortable. Now I see that over and over, that herbaceousness transforms like that, but so the big surprise, that was a big surprise more on the winemaking side. Like a completely outside the box picking timing that for it to make a wine that I didn't know we could make in Napa because you know, it's so bright and sagey, herbal, but ripe herbs, you know, that you know, you wouldn't think has that character you wouldn't think would be from Napa.

So you're very focused on organic viticulture, and organic viticulture is almost a neighbor to the word "natural," right?

Right.

And the natural wine movement is something that's gotten a lot of attention recently. You use inoculated yeasts. You don't use native yeasts. What is the thought process behind that and how does that make you different from say a natural winemaker?

So that's a good question. I think the concept of natural wine is something that's evolving, and I would like to see the definition evolve into, you know, to where it's focused on the health aspects of the wine, because I believe very strongly in the wine being healthy. Healthy for the planet and healthy in our bodies, and so I don't believe that inoculated yeast is any less healthy than wild yeast. Yeast is healthy. Yeast is healthy stuff.

There may be some GMO yeast. I don't use any GMO yeast. I don't even really know anything about GMO yeast. Maybe there's some GMO yeast that makes unhealthy stuff. I have no idea, but regular yeast that we use is all yeast that was isolated in wineries that was the resident yeast in wineries and it's perfectly healthy. So I think that's really important to get out there in the conversation is that's not the unhealthiness in the use of yeast.

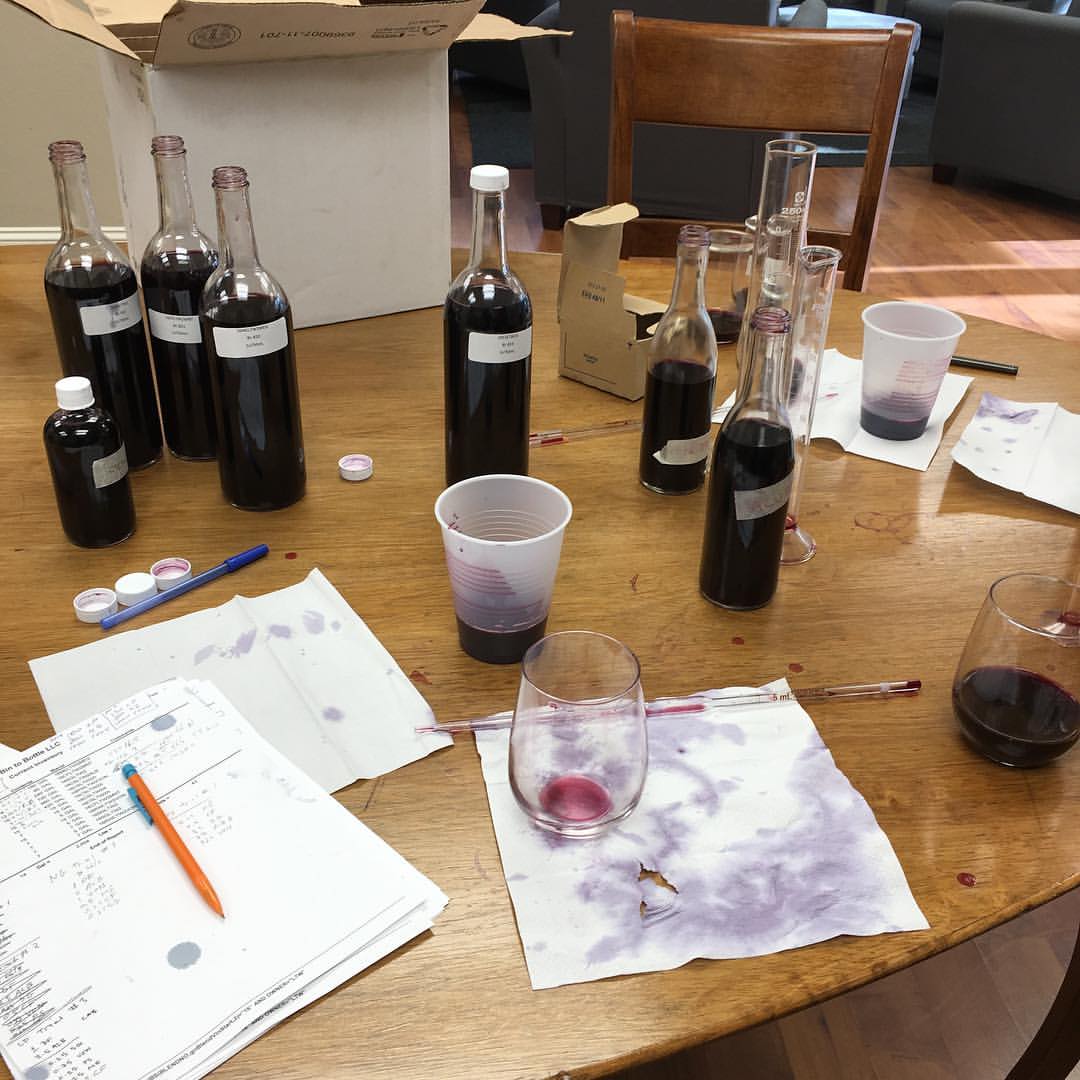

So why do we inoculate? We inoculate for a few different reasons. One reason is that we are still building our business. We don't have a winery, yet, so I'm custom crushing, and in a custom crush, you have a lot of different yeasts floating around that are all commercial yeasts, and a lot of them have more flavor impact than what we want in our wine, so I choose to inoculate with a yeast that has a low flavor impact, so that way, we don't get these weird esters or different characteristics of some of the higher flavor impact yeast, because there's a ton of different commercial yeasts. Some add a lot of flavor, some don't. That's number one.

Number two, the yeasts that we're using are very simple in terms of the flavors that they produce. They mainly just serve fermenting. So I think that I like the transparency that we're getting from the vineyards. Versus a lot of uninoculated fermentation is you can get a lot of complexity from the various species of yeast that sort of take turns fermenting and that complexity is delicious, but it's not what I'm going for, because I'm really focused on the vineyard and I'm trying to minimize complexity derived from the cellar. So not looking for that.

Then the third thing is if yeast are too stressed, whether from competitive organisms or from too much alcohol, they produce a lot of, yeast naturally produce chemicals like histamines, fusel oils, and I get migraines really badly, and so wines that have stressed ferment, whether it's stress from high alcohol or stressed from lots of microbial competition, I get a headache, and I can smell the stress ferment and I know and I won't drink that wine.

We drink a ton of wine that would be considered in the natural wine world in our house, because in most cases those are the wines that I get the fewest headaches from, but not in all cases. If it's natural wine that had a very stressed fermentation, a lot of brett fighting or a lot of lactobacillus or pediococcus or something fighting, they'll still, it might be 11% alcohol, I'll still get a headache from it, and so I try to hydrate yeast really nicely and I inoculate, I have a better chance of, again, uninoculated fermentations are perfectly clean and beautiful, too, but I'm just loading the dice on that being a clean ferment so they don't get any of those yeast toxins.

For more on Steve Matthiasson check out:

On Grape Collective Barbara Sturgis on Matthiasson's Tendu

Jon Bonné's San Francisco Chronicle column naming him Chronicle Winemaker of the Year for 2014

The 2015 New York Times piece the Wrath of Grapes

Levi Dalton's I'll Drink to That podcast

Buy Jon Bonné's book The New California Wine on Amazon

Amanda Barnes' video interview with Steve Matthiasson