In Southeastern France lies the picturesque, sun-drenched region of Provence. Cicadas loudly sing their songs in the dramatic hillside villages dotted with cypress trees and red-tiled roofs. The scent of wild thyme and lavender wafts through the air mingling with the aromas of Mediterranean cuisine: onions, garlic and tomatoes simmering in olive oil; the smell of freshly cut lemons, fish frying and meat roasting.

Within these fragrant hills stands a centuries-old winemaking tradition, with the town of Bandol producing some of the finest wines in Provence.

Bandol, Provence

Bandol is a beautiful port town in southeastern France with panoramic views of the Mediterranean Sea. Granted its AOC (appellation d'origine contrôlée) status in 1941 with just 10 wineries, it has since grown to about 50.

The vineyards are situated on terraced hillsides facing south, where the heat is tempered by cool sea breezes. Among the vines, olive trees and fruit orchards thrive, interspersed with wild-growing "garrigue," a French term describing low-lying Mediterranean shrubs and plants like rosemary, lavender, thyme, and juniper. These plants flourish in the limestone-rich soil, imparting an appealing herbal aroma to the wines.

Bandol is the only French AOC where the Mourvèdre grape has a starring role, with Grenache and Cinsault playing the supporting cast and a couple of others, Carignan and Syrah, in the chorus. Mourvèdre makes red wines of depth and power which, with proper blending, soften with time and become silky and elegant. The Mourvèdre-based Bandol rosés are darker in color and fuller-bodied than other Provençal rosés. They are fresh and lively when young and gain complexity and depth as they age.

Domaine Tempier

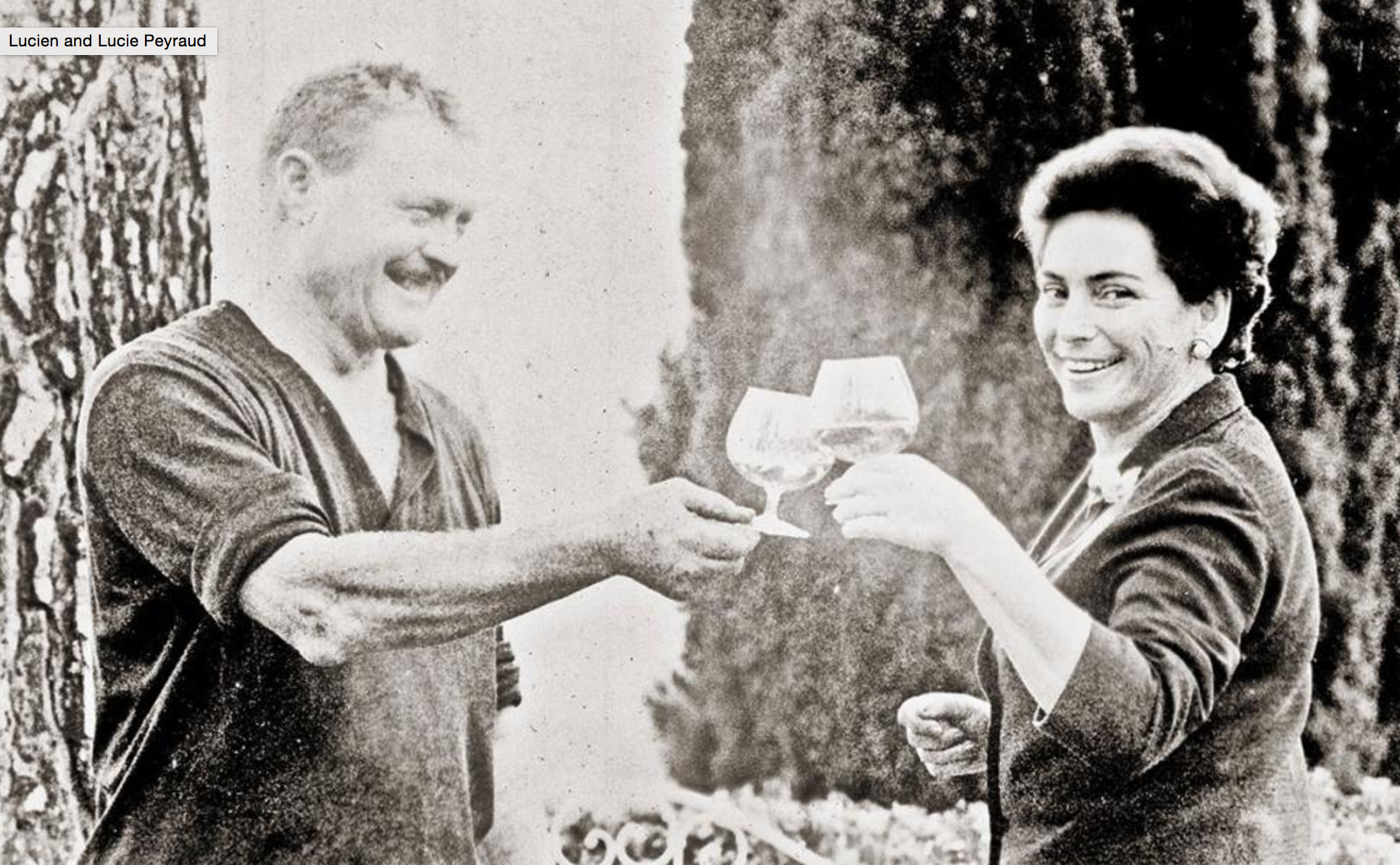

The fabled Domaine Tempier has a long history dating back to 1834 when it was an active farm distinguished for its red wines. Leonie Tempier, then the guiding force behind the winery, was more concerned about quality than quantity when it came to her wines. In the 1930s, Leonie’s granddaughter, Lucie (known as “Lulu”), married Lucien Peyraud (photo right and below), an aspiring winemaker, and was given Domaine Tempier as a wedding gift from her father. Lucien fell in love with Mourvèdre and became instrumental in reviving the grape, and the whole Bandol wine-growing region to its former glory.

Mourvèdre had been devastated by the phylloxera epidemic in the late 1800s, and many of the vines around the area were ripped out and replaced with peach and apple trees or easy-to-grow, high-yielding grapevines which produced mediocre wine. For years Lucien was president of the winegrowers organization that promoted Bandol wines. His passion and advocacy gave him recognition as the “spiritual father” of Bandol.

Lulu was right there alongside him, raising their seven children while also selling Tempier wines to restaurants all over the world. At home, in the charming farmhouse amongst the vineyards, Lulu carried out the Tempier tradition of having a rotating cast of family, friends and wine lovers gathered around the table enjoying copious amounts of her homemade French hearth cooking. The evening would start off with a glass of cold, refreshing rosé and continue with the hearty red wines, which paired so well with the Provençal cuisine on the table.

Life, food, and wine were all intertwined here. Chef Alice Waters views Lulu as an inspiration for her renowned restaurant, Chez Panisse, located in Berkeley, California. Similarly, Kermit Lynch, an American author and wine importer, became so enchanted with this magical place that he bought a home nearby. The days of hosting lengthy meals may be over, but at 99, Lulu still resides at the farmhouse and enjoys a daily glass of Tempier red wine.

When Lucien retired in the early 1970s (he passed away in 1996), the winemaking torch was passed on to their sons François and Jean-Marie. For 30 years they produced vibrant wines while continuing their parents' legacy of embracing the future while honoring the tradition of caring and respecting the environment. They installed modern equipment in the cellar and focused much of their attention on promoting the estate’s three unique, single-vineyard wines: La Migoua, La Tourtine, and Cabassaou.

Preparing for retirement in 2000, François and Jean-Marie hired Daniel Ravier as manager and winemaker. Ravier now carries on the great tradition and style of Domaine Tempier in the vineyards and in the completely refurbished cellar. The property, organically farmed with no chemicals ever used in the vineyard or winery, is now completely biodynamic as well.

Grape Collective recently talked with Daniel about carrying on the winemaking traditions of Bandol and Domaine Tempier.

Grape Collective: Tell us about the history of the estate, Daniel.

Daniel Ravier: The estate has been part of the family since at least 1834 when they bought the place. The name of the domaine comes from Lulu's maiden name. She was born Tempier, and she married Lucien Peyraud in the '30s. The property was given to them as a wedding gift and that was the start of renewing part of the cellar of the estate in a way, because it had a period during the beginning of the 20th century where it declined a little bit because of difficulties in the wine business producing more fruit than anything else.

When they joined the property, they started to renew it, and of course, it was at the same time as the beginning of the appellation, which became very important for Lucien and Lulu because they were part of that branch of very, very utopist producers who started the appellation in the late '30s, beginning of the '40s. Lucien has been considered the father of Bandol, as he was the president for 37 years.

In terms of your background in winemaking, how did you get involved in winemaking?

I grew up in the Savoie. My father was a farmer. In fact, except for cows, my father didn't have any interest in any other farming. I'm joking, but it's nearly the case. Finally, I entered school and began learning agronomy, and in agronomy, we had lessons about oenology. I thought that was really, really interesting. That's why I changed my decision and started focusing more on wine. learned it in Montpellier for about two years and first started to work in the region in '87 as sort of a probationary period in one of the estates around here.

The owner of the property just gave me sort of a virus of Bandol, I was really really impressed by the region. Of course, it's a very nice region to live in, but I was really also impressed by the style of wines produced, based on Mourvèdre-consistent wines, really, really amazing, with great ability for aging, great ability for changing, all of the time. It really impressed me, and I almost didn't want to leave in a way.

In 2000, I was working at another property in Bandol when the two brothers, the Peyraud brothers, asked me if I wanted to join Tempier, as they were in the process of brainstorming with their sisters, thinking about the succession problem. They thought it was maybe easier to have somebody not from the family to be in charge of the property so François and Jean-Marie, the two brothers, could take their retirement, and I have four of their five sisters back into the decision system, so they modified the status. It permitted the sisters to be members, shareholders, and members of the decision taken on the property. They hired me in 2000.

Since 2000, I have been driving the property, but always under the control of the family board and always under the shadow, not only the shadow but the spirit of Lucien and Lulu, which is very important. The idea was to keep producing the same style of wines, using of course the great base that they have on the property.

Talk about the terroir of Bandol. It's in the very south of France, and it's pretty warm. What are the climates and soil like here in Bandol?

The terroir of Bandol is very, very attractive for different reasons. The soils are really interesting in a way because they are mostly limestone and clay sub-soils and the majority are about 100 million years old, so very young sub-soils. You have some parts that are older in the basin. The quality, for me, the quality of the soils are remarkable in the fact that they are quite rich enough. We are in the south; we don't have that much rain, but we have soils that are profound enough, not too profound of course, but profound enough to have good conditions to drive grapes we are looking for, mostly Mourvèdre of course, and then Cinsault, Grenache, Carignan, Syrah for the reds, but mostly Mourvèdre, and these conditions are very good for these grapes.

The other aspect is that we are lucky to be in the sunniest place in France, so very good conditions for maturity, close to the sea also to cool the system down, a little bit, it doesn't mean that it's green enough, with global warming, we could see that we've had a gain of at least 15 days in about 30 years, so it does help us to produce wines that are probably more approachable when young, but I'm not sure that the balance is equivalent to what it was in the '80s for example. I'm not sure that the wines that we are producing today are going to be able to age as the wines from the '80s could.

How would you describe the character of a Bandol red wine, which is really kind of the flagship of the region, is it not?

Because of the rules of the appellation that are very restrictive, because of the yields, because of the way you have density, the way you have the dry vines, for Bandol reds you must have a minimum of 50% of Mourvèdre in your wines, maximum 95%, which means you need to have it in wines, and you need to have something in addition to the Mourvèdre, which is very important, this is part of our history. I think because of these very restrictive rules, and the soils and the conditions we have, plus the aging of 18 months in wood, these wines could age for a long long time. They are becoming more elegant, silkier, whereas Mourvèdre, when young, can be a bit impressive, can be a bit like an adventure. When aging, the tannins are becoming silkier, more elegant, and the wines can be very complex.

They have great aging potential, and I think it's probably due to the Mourvèdre, and also due to the conditions that we have in the region, that's very important.

How would you describe the taste of a Bandol? If it's got a little pepper to it, it's got good fruit, I mean, how would you describe it?

In a way, I should say, I know how to make the wines, I'm not a very good at describing them, but if we should say a few words about the reds of Bandol, I would say that of course because of Mourvèdre, you are going to have more like black fruit, black currant. When young of course you have the spicy side, you have the structure, and then when aging, you have more like tobacco, venison, all these kind of aromas you can find in an old Bandol, but even in very old Bandol, you still have that very pleasant fruity aspect, it just needs to be decanted. It's a minimum you must do with every Bandol, whatever the age, is decant it. It makes them more elegant by far.

Mourvèdre is a reductive grape. We age them in big vats, for 18 months, but for big vats close to the reductive point, so if you want to enjoy it, decant it. It's always, always better in my opinion.

You farm organically, and you've now gone one step further and now are biodynamic. What were the reasons for a) being an organic farmer, and b) taking the next step and going biodynamic?

Well being organic was for me, obvious, in evidence, for three major reasons. The first one was Lucien was organic so it was always driving the property organically, and François and Jean-Marie continued in that way. That's sort of a tradition for us. The second reason is that, to pay a minimum of respect back to the terroir, and I do believe we have very nice terroir in Bandol and especially at Tempier, I have the feeling that we have to be organic, at least. The third reason is that for myself and the guys working in the vineyards, I prefer to be organic anyway and not to use any chemicals where I'm not sure what the effects could be in the next 30 or 50 years. To avoid any problems, I prefer to be organic.

Because of tasting some of the wines from lots of regions, regions that are looking quite similar to Bandol, where good friends are making biodynamic wines, I thought we had to make a step further by moving to biodynamic. It took us about 10 years, because we first started with herbal teas, I don't know the English names of the plants but it's ortie, prêle, achillea (nettles, horsetail, yarrow); we started with that. I'm going to be honest, if I say that we have been biodynamic for about 10 years, that's not the truth. The truth is that we've finally moved to biodynamic, all the processes, about three years ago.

For us, the idea was, we did experiments with just sharing parcels and seeing what's going, it seems to be really interesting, maybe because we believe in it, it's part of the deal, too. Finally, we decided to move everything to biodynamic and the idea for us is to have livelier soils, to have plants that have a good environment, and to provide good conditions for the plants. If we have any gain in this area, that could be great. That's not the first objective. The first objective is really the soils and the relationship between the vines and the soils.

You dry-farm as well, you have to dry-farm, it's a regulation in Bandol that you have to dry-farm. How does that impact the plants?

In fact, we are lucky enough as I've said, that the soils are quite profound. They are not very rich but they are quite profound. We don't have that much rain here in the region, and most of the time, we are in the south so the problem is that the rain is most of the time heavy rain. The majority of the rain we are receiving is, generally speaking, storms, and that's one of the aspects here, is that some of the rain we do have is just going directly to the sea because of being too heavy. For different reasons, I think watering could be a problem for us in the future. I would like us to avoid watering as long as we can, because, first, when you start watering, from what I've seen everywhere, to when you stop watering, you are reducing the differences in between the vintages. Things are becoming more and more, year-to-year, quite similar. I don't mean that there are no differences, there are still differences, but fewer than if you are not watering.

The second aspect is that you are sort of unequally accessing water. We are lucky here in the south, we have a very big reserve of water with the Alps and the Ardennes. Part of the Alps are falling here in the Mediterranean Sea, so I don't think water is going to be that much of a problem in the future. The access to water is not the same in all places and unfortunately the places that would need the most water are not the ones that are going to be watered. It causes an inequality that is not very good for the appellation, I think.

The third point is that, despite all this, I think that in the future, if there is any competition for water, we're not going to be the first to be served. That's sure. Lots of people are coming down south here in France to live from up north in France and up north in Europe, in fact. It means there is going to be more and more housing, less and less vines of course, but more and more housing, more and more demand for water for human consumption, and, because of that, I'm not sure that we're going to be the first to be served. If you consider that, I'd prefer to avoid watering as long as we can.

Rosé has become a big success story internationally, and where we are right now is one of the areas that has become very very hot. How has this enormous, sort of international rosé craze affected Tempier and also the region?

Speaking about the region, that's clear that now more and more people are concerned nearly only about rosé, I know some producers in Coeur du Provence that are producing at least 90% rosé. It's also true that the average percentage of Bandol dedicated to rosé is higher than it was in the past, because now we are close to 75%. There are a few producers like us who are staying with probably more reds than rosé. Things could change a little bit for us as we are on our way to having a few more vines and then these vines are going to be part of our production of rosé, but I think we have seen this happening for about 10 to 15 years now, and the question is to know if it is going to be consistent in the future. For me, I think as long as we are going to be able to produce rosé, that structuring of Mourvèdre-based, that could have a very intense palate that you could marry with lots of food, for lots of kinds of parties or whatever you want. This is going to be a good market and I don't think it's going to go down, honestly.

I am always wondering about these fashions with the very pale rosés that are not consistent. You could find very interesting pale rosés that are consistent, that have a very deep soul, you know, consistent fruit, length enough in the mouth. You could find some like that are very pale, but not many. The problem with the majority of the pale wines is that they are pale just to mask the lack of consistency that they are showing from the vineyards, from the attention that has been paid to the vineyards. That's a very big problem in my opinion because it could ends up being like a sort of fashion. You know how fashion is, it is going to turn. In time it's going to turn, I have a feeling that it will be a little like Beaujolais Nouveau. There are still some very good producers of Beaujolais and Beaujolais Nouveau of course, and these guys are going on, but the majority of the guys that were producing standard wines or less only because it was Beaujolais Nouveau, I'm wondering if it's not going to be the same as the rosé. People are going to say, "Oh no, it's too pale. I don't like it."

Bandol is a bit specific because of Mourvèdre, and because of the yields, because of the terroir, giving us an intensity in the mouth that is really interesting, and make it more like, we call it, rosé de gastronomie, and also Couer du Provence, that are really good also for rosé de gastronomie, but you know, it's just to make a comparative point. Saying something more is our imperative and something more for having this wish. I guess Bandol is a bit more stable in that regard and I hope that we are, at Tempier, one of the domains that is really interesting from that point of view.

What is your philosophy of winemaking and has it evolved over time?

Yes. I don't know if I have a philosophy of winemaking. Let's say it this way, because my idea when coming to the property, when joining Tempier, was to follow what has been done for decades and that has been working. Of course, with global warming, things have changed, so we have been obliged to adapt a little bit, especially for rosé. For the rest, there are no changes only in the way we are making wines. Of course, because of global warming, the wines have changed a little bit. I couldn't say the contrary. I hope they are still in the same spirit. For the rosé we have been obliged, for example, in the past, and before 2007, all the wines, all the rosés were achieving the malolactic, which is not exactly the case now. Part of the rosé, part of the blend has achieved the malolactic, only part of the blend.

It could change a little bit of the amount of wines that are achieving the malolactic, because if we were achieving totally the malolactic now, I have a feeling the wines would be a bit less aromatic, and a bit too heavy, probably. We need some lift in the wines and blocking the malolactic could help us, even if it's not the best way, but again, we are following what we have from the weather and global warming is here, it's obvious. If you're not convinced about that, just ask wine producers. Everybody knows, it's obvious.

You have a group of grapes that you're allowed to use to make a Bandol. What are those grapes and how do they complement each other to create this wonderful wine that you have?

First, the idea of blending is very important for us. The more you go down south in France, the more you have blended wines and I think it's part of our history and we have to keep that. It's very important to us to have different grapes. Of course, our key grape is Mourvèdre. It's the king of Bandol, it's obvious, but we must have other grapes. The grapes we are allowed to use in addition to Mourvèdre are more than any other, Grenache and Cinsault. You are also allowed to use Syrah and Carignan, limited to 10% each. This is very important to keep the idea of having Mourvèdre as a key grape, but always with a side to Mourvèdre, something else. That's very important.

Even if it's a small percentage, we are limited to 95% Mourvèdre, which means that you must have 5% of something else, but it could be five, it could be 10, it could be 15, it could be 20. There are, more or less, lots of wines in Bandol, red wines that are in between 70 and 90% Mourvèdre. That's the general average. We have very few that are close to 50%, the tendency is to have more Mourvèdre, but always with something added to it, this is very important.

Each grape has its interest. Mourvèdre is bringing the structure, bringing the identity of Bandol, the rough aspect on some tastings that you could have. On the other hand, it's also giving the structure to the Bandol, but then, Grenache is bringing some roundness, some spice. Cinsault is bringing finesse, obviously. Carignan could bring freshness and very specific aromas, more like cherries, and very very interesting. Syrah is funny. On its own, it's too ripe, it's not very interesting. When you blend it, it's giving more complexity to the wines anyway, always, even if it's a very small amount.

In the rosé, it's still a bit the same. Even though we are not using at Tempier any Carignan or Syrah for the rosé. We keep them for the reds and so it means that the rosé is Mourvèdre-based, usually around 55% completed with Grenache and Cinsault.

In terms of global warming, how has that affected the way that you grow your grapes and make your wine?

Global warming has obliged us to change little aspects on the way we were working. Of course, in the vines first, by having more canopy so, putting out, in the major part of the case, wires where we could put out more wires, back to what we call gobelet and having more driving vines, more like bush-style in a way, to have more shadows, to also try to delay a little bit the maturity. Changes in choice of rootstock, how we go about new plantations, changing our system of training the vines, to lower the effect of global warming. Then in the cellar, one of the major changes was the "malo" on the rosé that we've been speaking about before.

Then, in the cellar, I don't have the feeling that we changed that much in our process. The wines are changing a little bit. The reds are more approachable probably than they were in the '50s until the '80s. Far away more approachable now, because of global warming the ripeness is making things rounder, tannins, more ... How could I say that? ... More sweetness, there's no sugar left, but sort of sugar-ness in the wine that is rounding the tannins of the Mourvèdre, making them more approachable, that's one of the good aspects of global warming.

The bad aspect is probably that the pH is a bit higher than it was in the past and I'm not sure that the wines are going to be able to age as long as they could in the past. That's one of the questions we do have now about that.

We have made some changes, and it's very hard to make changes. We are speaking about rootstalk, for example, you are planting vines for 50 years at least. What's going to happen in 50 years with global warming? I don't know. We can't move Bandol, Bandol is here. We can't move up north somewhere. I don't know, change the rootstalks? Think about new grapes? I don't know. I don't know what are going to be the future possibilities that are going to be given to us, honestly.

You've just made a major acquisition, which is going to change your business. I mean, you're going to go from 40 hectares to 60 hectares.

Well, we are always facing a huge demand for our wines. We can't face the demand. I'm spending more time refusing to sell wines than saying yes. We thought it was time for us to think about having more wines to produce. We didn't want to buy grapes. We wouldn't. We were looking for something and finally last week we ended a very long-term deal with a family, and we bought another property that is called the Domaine de la Laidière, in Bandol with a very interesting position, especially considering rosé and white wines. Great terroir, I'm sure about that. I think it's very consistent also for the reds. It will probably take a little bit more time to adapt everything to the way we are working, but it's very interesting and I think it's good for the future of the domain.

I don't know what we are going to do. We are probably going to start by continuing with Domaine de la Laidière, and Tempier on the other side, but when the vines should be at the level probably sort of merge with part of Domaine de la Laidière, with Tempier, I think. Because it's very consistent terroir and the other aspect is that this terroir is close to La Migoua and we have some soils that we already have in lots of our vineyards. It could be interesting, different exposition, more east and southeast. I think it's going to be really interesting to see what's going on this space.

Tell us a little bit about the terroir.

One of the aspects that Lucien, François and Jean-Marie, the two sons, developed in the late '70s was making two wines from different terroir. In fact, it appears that when tasting with some importers, these importers were saying, "Whoa, whoa, stop. These two wines are totally different, so why are they different?" Jean-Marie said, "That's obvious. This is coming from here and this is coming from here." So it finally ended that the Peyrauds decided to produce single-vineyard cuvees, La Migoua, La Tourtine and, in '87, Cabassaou, that are vinified and aged in exactly the same way, and the Classique, too, everything is done the same way, but the places are so different that the wines are different. The blends are different, but the places are more important, to my opinion, in the resulting to the wines. If you have any opportunity to taste these wines, you will see that that they are really, really different, and the differences, again, are only coming from the place and the blend, of course.

In La Migoua, you have a bit less Mourvèdre, but you have more complexity because of the geology. It's a very important geologic accident, it's higher elevation, more wild as a place, let's say, more small passes of vines in garrigue. These are the major points, but there is a bit less Mourvèdre in La Migoua, which is, the blend is usually around 55% Mourvèdre, but it is with a lot Cinsault, 27% Cinsault, and then Grenache and 3% of Syrah, as an average.

La Tourtine is on another slope, back on soils that are more traditional, limestone and clay Bandol on top of a slope, very windy and sunny but a very nice place for Mourvèdre, so generally La Tourtine is around 85% Mourvèdre completed with Grenache 10% and Cinsault 5%.

Cabassaou is a lower part of the slope of La Tourtine, protected by the mistral, small terrasses, a very interesting place, just to show what could be a nice Mourvèdre and a nice place, so it's 95% Mourvèdre, plus mostly Syrah and Cinsault, Grenache.

Again, these wines are made exactly the same way, so if you have the opportunity to taste them, you will see that they are different because of these places.

Front page banner collage by Piers Parlett