Editor's Note: Vardo in the Vineyard is a series following Amy Tsaykel's life as she resides in an RV parked atop a vineyard in Sonoma County.

I recently conducted a casual, rather non-academic study of American pioneers — both real and fictional. Among its subjects were: the enduring Laura Ingalls Wilder, the rabble-rousing Calamity Jane, and Michelle William’s scrappy character from “Meek’s Cutoff”, among others. I reread Joan Didion. I swooned over Walt Whitman. I downed a shot of whiskey and cursed heavily, a la Trixie of Deadwood. After some assessment, I determined that pioneers bear the following similarities:

Chartering new territory (physical or otherwise).

Willing to take risks.

Don’t give a damn what anyone thinks.

Eyes on the prize, persistent.

Lucky.

Pioneers exist everywhere. Over the course of history, though, the American West has had more than its share. But I was never a fan of Western flicks 'til I moved to California. What was with all the dust and commotion? Who would want to ford a river, anyway? And why were these folks forever doing things to get their butts shot off? However, after fourteen years in this neck of the woods, I finally get it — some risks are just worth taking. I now revere pioneers; and the wine industry is an ideal place to witness pioneering efforts.

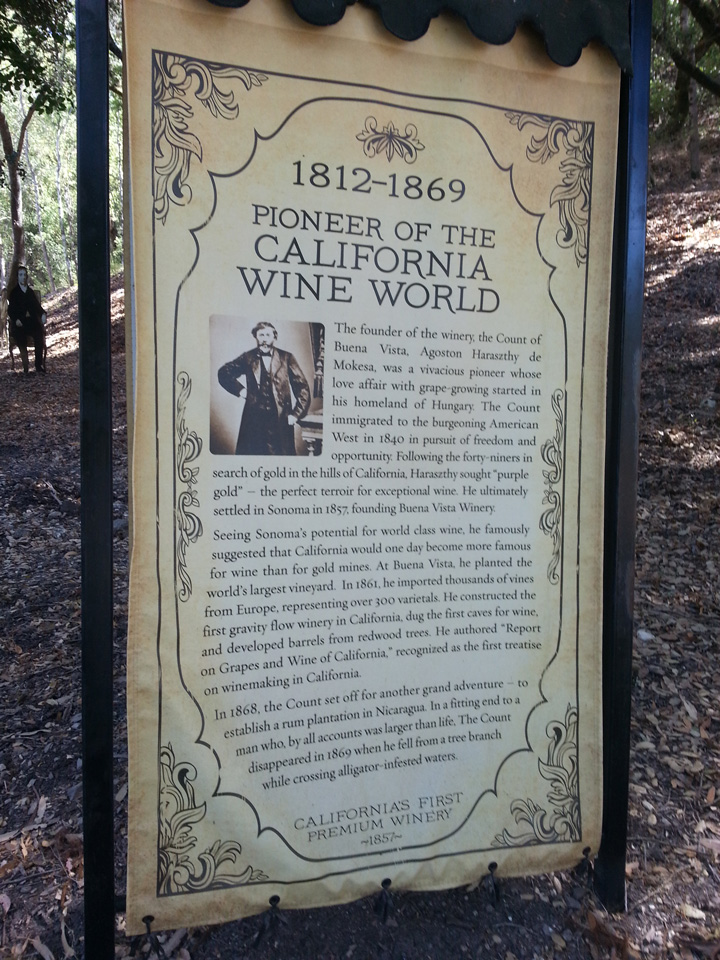

Here, in Sonoma, one need not look far for such inspiration: just down the road from my vardo is the remaining estate of a nineteenth-century Hungarian immigrant named Agoston Haraszthy. With his self-proclaimed title, “Count” Haraszthy (who had no legal claim to royalty) proved that pioneering and delusion sometimes go hand in hand.

Here, in Sonoma, one need not look far for such inspiration: just down the road from my vardo is the remaining estate of a nineteenth-century Hungarian immigrant named Agoston Haraszthy. With his self-proclaimed title, “Count” Haraszthy (who had no legal claim to royalty) proved that pioneering and delusion sometimes go hand in hand.

Left: Pioneer Promenade at Haraszthy's Buena Vista Winery pays homage to other pioneers including Kit Carson, Ben Franklin, and Robert Mondavi. (Photo Courtesy of Amy Tsaykel)

And why not dream big? As Willa Cather said, “A pioneer should have imagination, should be able to enjoy the idea of things more than the things themselves.”

Ideas? Haraszthy had plenty of those.

Prior to Haraszthy’s arrival in California in 1857, grapes had already been cultivated in California for several decades. Franciscan monks brought winegrowing to the area in 1782; subsequently, Russians planted the North Coast’s first vineyards. Legendary California political leader "General" Mariano Vallejo countered any Russian expansion by buying enormous tracts of land, and growing his own grapes experimentally. In fact, at the time, it was widely believed that the land was ill-suited to grape growing. Furthermore, there was no large-scale commercial production. But then came Haraszthy, who historian Charles L. Sullivan calls “an optimistic dreamer and an unbending idealist.”

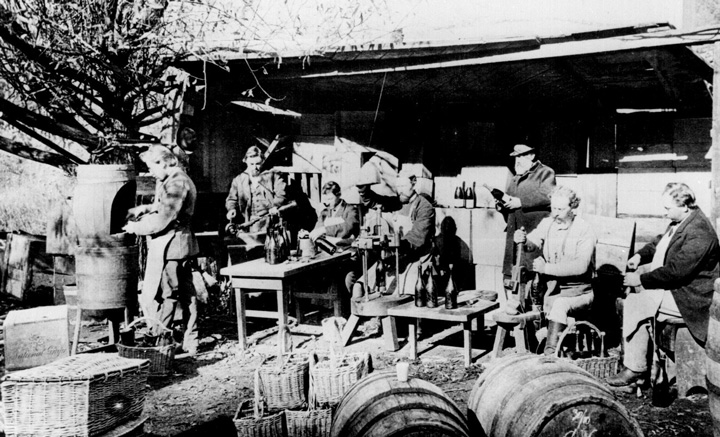

Haraszthy systematically staked out the best land in California for winegrowing and began investing in ways to process bulk amounts of fruit for commercial production. Among his efforts were the construction of the first wine caves in the U.S., the practice of submerged cap fermentation, and the development of a sparkling wine process. Finally, Haraszthy traveled Europe seeking the most suitable, high-quality fruit to grow in California, returning with 487 varieties of grapes and cataloging them all.

Unfortunately the Civil War was afoot at the same time, and economic depression and phylloxera laid waste to many of his efforts. Ultimately, some fruit and many wine production techniques survived theses challenges. Contemporaries and collaborators such as Jacob Gundlach and Charles Krug would benefit from Haraszthy's work, carrying the torch forward after his passing in 1869.

Below: Champange corking at Agoston Haraszthy's Buena Vista Winery. (Eadweard Muybridge)

Me? I am no pioneer. I am certainly not the first person on the planet to live in an RV trailer. I am not even the first person to on this block to do so. Still, I find it helpful to summon the spirits of mover-shakers like Haraszthy. Doing so reminds me to dream big. I will never be a countess, but I can strive to live like one — even if only in a tin-can palace.

These pioneers inspire me, also, to keep going. My goal of renovating my trailer and saving for a more permanent home will likely take time to reach, but meanwhile I am living the best, most sustainable lifestyle possible. (Blessings: counted.)

As Laurel Thatcher Ulrich writes, “A pioneer is not someone who makes her own soap. She is one who takes up her burdens and walks toward the future.”I regularly stroll the eucalyptus-lined neighborhood of Haraszthy’s former estate; its history is palpable. While I am walking familiar territory — I've lived in Sonoma for years, after all — I strive to forge a new path with every step.

House Wine

A few hundred miles from the original Haraszthy homestead in the former Austrian Empire lies the village of Illmitz, Austria — home to another family of wine pioneers. In the early twentieth century, Alois Kracher, Sr. (1928-2010) recognized the winegrowing potential of the foggy shores of shallow, vast Lake Neusiedl. Kracher was intent on maximizing the humidity in the Seewinkel region of Burgenland to cultivate “noble rot”, necessary for certain sweet wines. At the time, Austria’s wine industry was underestimated, but Kracher persisted. When his son, Alois Jr. (1959-2007) took the reigns, popularity of Austrian sweet wines soared. Now, a third generation, Gerhard, is at the helm of the winery and intent on carrying its legacy. Weinlaubenhof Kracher is widely regarded as one of the finest producers of sweet wine in the world.

A few hundred miles from the original Haraszthy homestead in the former Austrian Empire lies the village of Illmitz, Austria — home to another family of wine pioneers. In the early twentieth century, Alois Kracher, Sr. (1928-2010) recognized the winegrowing potential of the foggy shores of shallow, vast Lake Neusiedl. Kracher was intent on maximizing the humidity in the Seewinkel region of Burgenland to cultivate “noble rot”, necessary for certain sweet wines. At the time, Austria’s wine industry was underestimated, but Kracher persisted. When his son, Alois Jr. (1959-2007) took the reigns, popularity of Austrian sweet wines soared. Now, a third generation, Gerhard, is at the helm of the winery and intent on carrying its legacy. Weinlaubenhof Kracher is widely regarded as one of the finest producers of sweet wine in the world.

Find Kracher, select your level of preferred sweetness by number (1 = more dry). Alternatively, enjoy another sweet wine form the Grape Collective store.

Thanks to the knowledgeable Bradley P. Friedman of Napa, enology and viticulture professional, for generously sharing the story of another fine international wine producer.

Recommended Reading:

Sonoma Wine and the Story of Buena Vista by Charles L. Sullivan