Also called ‘malolactic conversion,’ ‘MLF,’ or simply ‘malo,’ malolactic fermentation is a practice in winemaking in which harsh and sour-tasting malic acid is converted into smoother-tasting lactic acid. To get a better idea of how these organic compounds taste, malic acid is the tart acid found in green apples and rhubarb, while lactic acid is the more subtle acid found in milk, butter, cheese and yogurt. Not only is lactic acid ordinarily more palatable than malic acid, it has a softer, rounder mouthfeel in comparison with malic acid, which is typically characterized as hard or metallic.

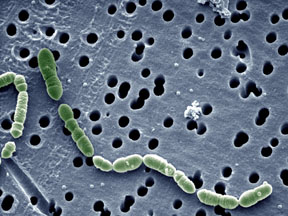

Often considered a second fermentation, MLF involves the family of lactic acid bacteria, Oenococcus oeni (pictured at right) and various species of Lactobacillus and Pediococcus.  It is a chemical reaction referred to as a ‘decarboxylation,’ meaning carbon dioxide is released during the process. While this can occur naturally, in winemaking it is generally instigated by an infusion of desirable bacteria, as some strains of bacteria can contribute unwelcome flavors and characteristics to the wine. On the flip side, with certain varieties that produce lighter-bodied fruit-driven wines like Riesling and Gewürztraminer, winemakers may intentionally prevent malolactic conversion in order to retain tartness and acidity in the finished product.

It is a chemical reaction referred to as a ‘decarboxylation,’ meaning carbon dioxide is released during the process. While this can occur naturally, in winemaking it is generally instigated by an infusion of desirable bacteria, as some strains of bacteria can contribute unwelcome flavors and characteristics to the wine. On the flip side, with certain varieties that produce lighter-bodied fruit-driven wines like Riesling and Gewürztraminer, winemakers may intentionally prevent malolactic conversion in order to retain tartness and acidity in the finished product.

The MLF process normally takes place at the conclusion of primary fermentation and is typical for the majority of medium to full-bodied red varieties. It is also used with some white grape varieties, like Chardonnay, as diacetyl, a byproduct of MLF, imparts a buttery quality to the wine. Additionally, grapes cultivated in cooler regions tend to have a higher acid content, much of which comes from malic acid. Malolactic fermentation is beneficial to wines made from these grapes, as de-acidification will result in a more balanced and palatable wine, enhancing its body and flavor persistence.

Another noteworthy reason for malolactic conversion is red wines that have undergone the MLF process while in the tank or barrel are considerably less likely to go through it while in the bottle. If malolactic conversion takes place in the bottle it is normally considered a wine fault, since the wine will appear to still be fermenting as a result of the production of carbon dioxide. The wine may also lose its fruit integrity and give off a displeasing aroma similar to that of cured meats.