Two days before interviewing Aurelio Montes at his Apalta estate, I was hanging out sipping wine and eating carne asada at a BBQ in an eastern suburb of Santiago. As the conversation turned to which winemakers we were going to visit, the interest level rose considerably when Aurelio Montes' name was mentioned. He is regarded as something of a hero in Chile, almost like a national sports star. We tried to think of other countries where a winemaker had achieved such broad popularity and affection and couldn't come up with any.

Part of the appeal of Montes is the that he is self-made. Chilean wine is dominated by three companies, Concho Y Toro (which is now the world's largest wine company), VTS and Santa Rita, which export 80 percent of the wine from Chile, according to Evan Goldstein's Wines of South America. Montes quit his job at 39 with five kids to start his winery and built a successful business with no inherited fortune but lots of hard work. He has also gained popularity as the Chile's international wine ambassador. Each Montes bottle label says "From Chile with Pride," a statement that has great resonance within the country.

During our visit, Montes took us on a tour of his estate. He is largely responsibly for developing Apalta (the word translates to poor soil in the local Indian dialect) and for creating a focus on developing lower yielding, hillside plantings rather than the high density but poor quality fruit of the valley floor. Apalta is a spectacular five-mile-wide amphitheater bordered by the Pangalillo hills located in the Colchagua Valley in central Chile. The Apalta winery was built in 2004 on Feng Shui principles, it is stylish, modern and efficient. Yet this is not a Frank Gehry-starchitect building - function and winemaking are at the fore. There is a wall in a central location of the winery where they display photos of their importers from around world.

Montes drove us up to a mountaintop ridge overlooking his vineyards in a old pickup truck. It is a majestic spot, even more so as the leaves were changing color. One field of bright florescent orange sat adjacent to a field with dramatic yellow hues. We shot our interview and got back into the truck. Montes turned the key and the truck wouldn't start. He called on his cell phone to several people on his team back at the winery but no one was picking up the phone. Awkward moment. We were stuck at the top of a ridge with Chile's most famous winemaker and he was getting a little hot under the collar. It took about five minutes for Montes to reach someone who could walk him through how to start the truck (there was an anti-theft button that needed to be engaged while turning the key).

Aurelio Montes talked to Grape Collective about innovation, dry farming, working with the legendary Ralph Steadman, and his path to entrepreneurship.

From left to right: Co-Founders Douglas Murray, Alfredo Vidaurre, Aurelio Montes, and Pedro Grand

Christopher Barnes: Aurelio, you were 39 years old, you had five kids and you decided to start your own business. What was going through your mind at the time?

Aurelio Montes: Well, in general terms, it was a nightmare. It was a very hard decision to take. My five kids were between eight and 15, and I realized what my future without a fixed job and without a payment at the end of the month might be. I couldn't sleep very well for close to a year.

Gladly along the way, and while the weeks and the months rolled over and over, I realized that we were doing the correct thing because we felt that there was music in the air, that something was going on, something was happening, and the trade, and everyone was recognizing our job, but it was very, very hard.

Aurelio, it was 1988 that you first started the business, how did you get the business off the ground?

Well, first of all I have to tell you a little story. I wasn't able to do it by myself. I invited three other partners and at the end we were four friends, partners, each one covering a different part of the business. I always think four winemakers wouldn't have made it. It was a winemaker, a marketing man, an engineer, and a guy who was in charge of finance.

Each of us covered a different part of the whole business. The others had other jobs but I didn't, so I had to start consulting wineries. Weekends and evenings were enough to start building all of this. Myself, I had to advise and consult different wineries with the same vision as my own in order to start building all of this.

As things started moving forward and working the way we expected, or even beyond that, I started to consult less and less. Today, I still have a consulting roles for very good friends and it's more of a spiritual thing than anything else.

Chile had traditionally been known for making inexpensive wine that was good for the price, and you were the first to go after the quality segment. How did you come to that conclusion, and how did you go about making these better wines that people really embraced?

I studied Oenology at Catholic University. I worked for two years as a winemaker with very well known, big wineries. Then I got to know the depth, the inside of the industry. I didn't know that while I was studying at the university. I realized that Chile was a blessed country, unique country to produce grapes, and with good grapes you can do good wines.

I saw that we have the coast, we have the northern valleys, we have the southern valleys, we have the Andes, we have this wonderful nourishing of the melting ice that comes to the rivers in the summertime. While making my wines in these different wineries, I realized that the range of quality was great. Some of the tanks were amazing quality wines, and they were all blended back to a poor wine in an inexpensive price. My thought was, why don't we start working the better wines and create another niche in the market, create another category of cheaper wines in the market?

That was my first thought, and then my second thought was, we're established in four different places, four valleys like Maipo, Colchagua, Maule, and so on, and I saw how many different slopes and valleys were there. It was putting all these ideas together - I said, "Okay. If we start refreshing the culture, planting in unknown places we will have the potential to grow quality vines and make great wine." That was my belief.

I told all my bosses to go for that. It was a bit dismissed, they were a little bit afraid of the competition with French, Spanish, Italian wines. I said, "Okay. I will put in the effort. I will try to do it." The market was prepared, the market was ready to receive better wines from Chile at a more fair price.

Making great wine is just part of the equation; you then have to sell the wine. Being in the position where you have this perception in the marketplace about Chilean wine, how were you able to succeed in communicating the message that you were making quality wine here in Chile?

I know, of course. Well, here is where the partnership plays a very important role. One of my partners, Douglas Murray, he was an amazingly talented man in marketing. He knew exactly how to approach each of the markets. We had a second positive thing that we were the first ones in Chile to come with this new trend, with the new idea, with this new concept.

As I explained, we surfed the wave all the way long. We saw the wave coming, we jumped onboard. There was a beautiful wave, and we surfed it from the very beginning. We were the first ones, we created a curiosity among the importers, distributors, sommeliers, and gatekeepers. Basically, they all said, "Well, these guys bring a proposition that seems to be interesting. Let's try the wine."

When they saw the wine was really of very good quality, the packaging was good enough, the name was good, easy pronouncing Spanish name, Montes. Things clicked, and worked much faster than we expected, so we were very happy with that.

To grow from zero to where you are today, what were some of the key things that happened along the way that were decision points that you look back on and you said, "Boy, I'm glad we really did that?"

The key thing that we did was innovation. We were totally different. We did different things that not everyone was doing. We're in front of these beautiful slopes, no one else before did it. These are expensive to clear, out of trees, stones, rocks, and slope and planted it. They thought we were crazy doing this but we did it.

Again, we brought clones from France to refresh our viticulture. The story of Chile as a viticultural paradise is that for the past 150 years we have been reproducing the same cuttings from the vines over and over. There were some endemic viruses and diseases that were already in the plant. I thought, "Okay. Let's get rid of these and let's bring a fresh new concept of viticulture."

We explored valleys, where we're sitting now, that no one else thought ever in planting a vineyard, we did. Then we went to Marchigüe, a coastal farm, we were the first ones to arrive there and plant a vineyard. Then we went to Zapallar in the north, no one ever planted a vineyard there, we were the first ones. All of this innovation brought curiosity, openness of the buyers. The whole world would say that "these guys bring an interesting proposition that makes a difference."

Tell us about this winery that you built and the Feng Shui principles behind it.

Again, it's a merit of one of my partners, Douglas Murray. He was very deeply involved in the Asian culture, Asian antiques, and how they do things in Asia. He was very fond of Feng Shui. When he proposed to bring the concept to the winery, we thought again that it was a different idea that no one else is doing.

We had a meeting with an expert, a Chilean expert, and we thought that the idea was brilliant, it brought happiness to our people. It doesn't mean it brings something magical into the business, but it becomes a nice place to work, where the natural light, the sun, the wood, the metallic things all come together.

The whole idea made a lot of sense and worked with the our new concept. Our people work with pride here. Being part of our company in this valley is a matter of pride. When they go to a pub in the afternoon and share a beer with friends and they say, "Well, I work at Montes," it brings me great pride.

Aurelio, talking about pride, I've talked to a few Chileans and when your name comes up and the name Montes comes up, people are very proud, proud of what you've accomplished, proud of what the winery has accomplished internationally. One of the things that people talk about is that on your labels it says ...

From Chile with pride.

From Chile with pride.

That's right.

It's something that seems to really resonate with the people in the country here, maybe talk a little bit about that.

Well, of course, with all, the whole industry, and we played an important role, it's a matter of pride. We changed, let's say, a poor viticulture of poor quality in general in 20 years or so into something very respectful. We are becoming important players in the international arena. We started exporting only 3% of our production in Chile. Today, Chile is a country that exports 70% of its production.

Of course, it is a matter of pride. We feel very proud of being part of this very blessed country. It's a beautiful corner on Earth with unbelievable conditions to produce grapes. We have rainy winters, we have sunny springs and summers. It's a place where you want to live, with a very good temperature, we don't have molds.

We're separated from the rest of the world by very powerful natural barriers like the Andes, the dessert in the north, the ocean in the west. All of these make a very unique country and we feel very proud to live in it, so why not say it with pride on the label, from Chile, we're proud of it. I think the whole industry feels the same.

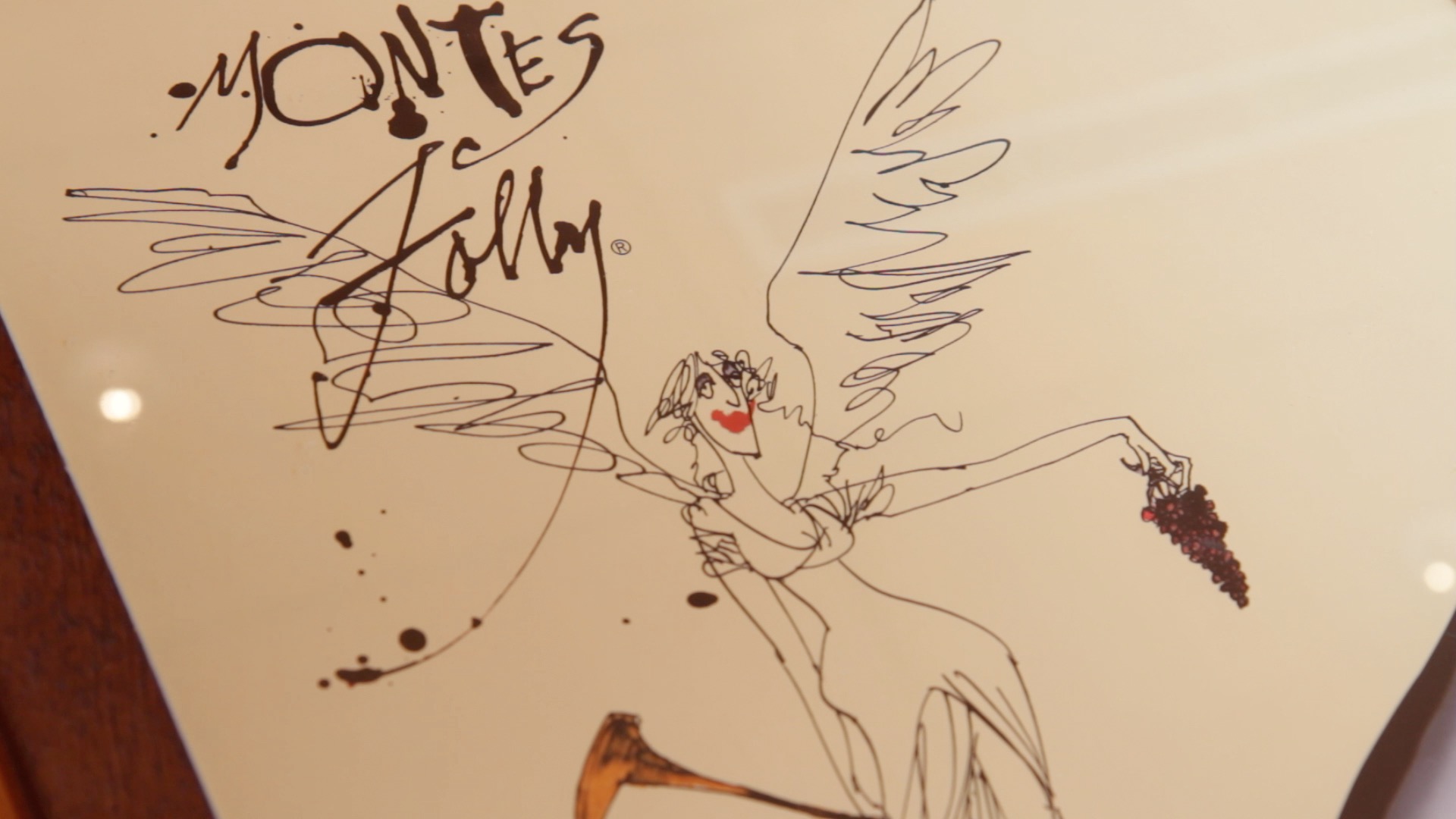

One of the things that I think are very distinctive about your labels is the illustrations. The illustrator Ralph Steadman has done amazing work, and many people associate him with Hunter S. Thompson and the work that he did with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas covers. You have his illustrations in your bottles, how did that come about?

Well, the story is an old story. We sold a lot of wine to Oddbins in the UK, and Ralph Steadman (left) was the illustrator of Oddbins in his monthly magazine. At some point Oddbins who was buying a lot of wine in Chile asked Ralph Steadman to go all the way to Chile, come down here and witness himself what was going on.

We were asked as Montes to take care of him, to look after him. We did and we became good friends. We moved around the country to the north, to the south. He got involved in the wine industry, we created a relationship, and when we decided to do some of our wines, especially the Folly, which is a crazy wine, because where it's planted there is ivy, we thought a crazy painter or illustrator would be amazing to have make out label.

We asked Ralph Steadman if he would make the label for our wine called Folly, and he said, "of course. I'm glad to do that." Every year he changes the label because he painted lots of paintings during his visit to Chile. He's got beautiful landscapes of the north, of our coastal area, the volcanoes, lakes, Patagonia, so we changed the label every year. He even painted a tipsy angel on the back label, a drunk angel, because he thought the wine was so good that even the angel on the label would get drunk.

Aurelio, tell us how your viticulture has changed over the years, since you started in 1987.

One of my views when I started with Montes and wanted to be innovative and create new things, was that although we had good varieties like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, they were overused and over-produced, and there were some endemic diseases, viruses, and so on. I decided to bring fresh clones from France, no viruses, improve quality, refresh our viticulture, so that was the first step.

Secondly, the trend of Chile was to plant the valley floor with fertile soils, and with a lot of water available, the yields were too high and of course the quality wasn't that good. My view, moving around the world, visiting the Rhône valley, German Rhine, the Mosel, and so on, I realized that we had so many mountains in this country that we could use them.

Having a different type of soil, a poorer granite soil, where if you irrigate or if there is some rainfall the water drains out very fast, so the plant is always struggling. You control the vigor, you control the canopy expression, you control the yields.

We decided to go uphill. Again, we were meant to be crazy in this country planting the hillside. We had to remove tons of stones rocks, bushes, and trunks of tress. Then we started planting the slopes, the hillsides, and we realized that the quality was amazing. Lower yields, highly concentrated, much more ripe tannins, good expression of flavors and so on. We felt that we were heading in the right direction. That was the second point to address.

Then the third one was that we were established in 2 or 3 different valleys in Chile, and we thought that there were so many other alternatives unexplored, undiscovered. We started to move to new spots, the coast, hillsides, some valleys totally poor in terms of agriculture that people thought unsuitable. We proved that the vines did grow, and did grow very well there. All of these elements created a kind of little revolution in viticulture.

Aurelio, tell us about dry farming, it's something that doesn't really happen in the part of Chile where we are.

Well, dry farming is something that is used worldwide. All of Europe uses it because Europe has a lot of rainfall during the summertime. You have to realize that Chile, because of the position, geographical position, because of the Humboldt Current and the presence of the Pacific Ocean, it doesn't rain in spring or summer.

Going dry farming is quite risky, but global warming is hitting Chile as well, we're no exception to it. The rainfall comes less and less, it's more scarce. My thought was I want to know hell before I go there forever, I wanted to know how to react if someday there's no rain anymore. We stoped irrigating a small part of the vineyard, with the risk of killing the vineyard, but I was determined to do it.

We were very impressed and astonished to find out that the vines didn't die. They could react to drought, they could adapt themselves to the drought, they dug deeper into the subsoil, and of course we helped with some wood covers, shortening the canopy. We found that lowering the yields we could live without irrigation.

From the year 2012 onward in our Montes Alpha range, we decided to go dry farming. We are the only winery doing this in these valleys. If you go to the southern valleys where there is some rain in summer they normally do dry farming, but in these valleys it's quite unique.

How much water are you saving?

We're saving a lot of water. Just to give you a couple of figures for you to retain, from 4,000 cubic meters we went down to 1,000 cubic meters per hectare. The amount of water we are saving is exactly the need of 20,000 people per year. We are going in a very sustainable using less water, less energy, and having water for human needs.

When you dry farm, how does that impact the quality of the wine that you're making?

To be very honest when I started the project of dry farming I was looking to save water without affecting much of the quality, but what we found out after five years, we have been doing a lot of research, is that we saved a lot of water, and we improved the quality, too. It was something that I didn't expect.

The yields went from 10 tons to the hectare down to five or six, nearly half. The cluster size from 150 grams went to 90, just a smaller cluster, much more concentrated, the tannins are riper, high concentration of flavors and color. Phenolics, everything is much better. As an extra bonus, we got a better quality out of this dry farming.

In terms of the Chilean wine industry, what are some of the challenges that it faces?

I would say that technologically speaking we are up to the level of any wine producing country, even the most modern that could be, Napa Valley or California. We have very fresh viticulture; we have wonderful tools to work with in oenology. I would say that the biggest challenge that the wine is facing today is the market.

We have to prove to the world that we are able to produce amazing quality wine. We have to keep working, producing high quality wines, we shouldn't lose focus. The Chilean wine industry must always be aiming towards quality, to over-deliver and teach the people that Chile is a good alternative in terms of wine.

What do you see the future of Chilean wine? People have talked about Carmenère being the grape of Chile? Is Cabernet Sauvignon the grape of Chile? Is Chile going to be a country like Argentina that puts itself behind one varietal or are you going to focus on many varietals?

I would say that the name of Chile is diversity. We have wonderful natural conditions. We have today more than 16 different valleys. We have proven that many different varieties work pretty well in all of these alternatives. We're producing amazing wines in the coastal region with the cold climate like amazing Sauvignon Blancs, Pinot Noirs, Chardonnays, Rieslings.

We're producing amazing wines in the Central Valley, the best reds, Syrahs, Cabernets, Carménère of course. We're starting to explore the foothills of the Andes. We are not standing behind an specific variety. I would say that the big attractive part of Chile is its diversity and quality across the board.

Talk about the terroir of Apalta, this is a very unique spot that we're in right now. How is the climate and the soil unique in this part of Chile.

Well, we are within Colchagua Valley and Apalta is a little spot within this big valley. We have very unique conditions here. We have this beautiful range of mountains behind ourselves facing the north. We have a river, the Tinguiririca River in the south that creates a microclimate here.

This valley being slightly warm, the fact that we are facing south, the south side is the cold side in Chile. It's cooler, so we have a late sunrise and an early sunset. In addition to that, the temperatures are not that high, we have a very specific granitic soil, a decomposed granitic soil with a certain component of limestone and clay that make the soil fantastic to grow, I would say, most of the red varieties.

I would say that Syrahs, Carménère, Petit Verdot, Cabernet Franc are the most amazing varieties that I've produced in the slope. As you move down to the valley floor the Cabernet Sauvignon becomes an amazing variety that has adapted very well, too.

Chile has always been know for inexpensive wines, how does Chile promote what you're doing here? How do you get the word out to the rest of the world that you're producing quality wines?

Well, there are many ways of course. I think that I'm becoming a little bit political. I think that the government should realize, that investing in the image of Chile is very important. We have a lot of priorities in our country, but investing on image is so important.

People should know about Chile, and should know about Chile beyond wine. They should know about its beauty, the natural beauty that we have in our landscape. They should know a little bit about our food, we have amazing local food, and they should know about our people. The Chileans are amazing, friendly people. I think that we should start bringing more people. Although, lots of foreigners are coming, we should make an extra effort to bring more people, especially from the wine business.

Of course to realize and to witness all what we're seeing today, this beautiful landscape, the granitic soils, the commitment to quality wine, it will take time. It doesn't happen overnight. It will take years and maybe a couple of generations but we're going in the right direction and we shouldn't stop.

Aurelio, you created a winery in Argentina, in Mendoza. You also started making wine in Napa. Tell us a little bit about what made you decide to go outside of Chile to make wine.

At some point, after 15 years of Montes, we had already established a brand in the market which was quite unique. We felt that we were quite consolidated here, but we still had energy to burn. We wanted to do something else. Chile was covered, so the natural first step was to move to Argentina which is next door.

It takes, by plane, half an hour to get there, or four hours by car. We have a kind of similar culture with the people there, with the winemakers, with viticulture. The first step was that and we don't regret it. I think the things have been going very well there. We established a very nice winery, we own land, we own our own winery.

My son Aurelio Jr. is in charge of that operation and he lives in Mendoza in Argentina. It's been a wonderful experience. We found friendly people, very focused into quality as well. We made a second brand that is quite known, not as known as Montes but it's quite known, it's called Kaiken, the name of this wild bird that flies across the Andes back and forth, the same as we did. We did it and we're happy. It's been a success in my opinion.

Then after four or five years that we started in Argentina, I felt that we still needed to do something else to prove to the world and prove to ourselves that we could do wine anywhere. Napa is kind of a cathedral of the New World quality wines, and we wanted to be side by side with the Mondavis, with Francis Ford Coppola, with all these trendy names, the Screaming Eagles and the Harlans and so on, and prove ourselves to the world that we could do good wines there, and we did it.

In the year 2006 we started a very small operation. We process our wines in our winery in Carneros, in the southern part of Napa Valley. We are already in the market with very good write ups and very good comments on the wines. It will always be a small operation, but it's a little bit like the cherry on top.