Fattoria di Fèlsina is known as one of the top quality wine producers in Chianti Classico. Fèlsina has always been dedicated to quality wine production and has focused its Chianti Classico solely on Sangiovese, rather than a blend with some added international grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon to add colour or Merlot for softer mouthfeel. Giuseppe Mazzocolin has run the estate since the late 1970s and has invested heavily in organic viticulture and terroir-focused winemaking.

Monty Waldin talks to Mazzocolin about what makes Fèlsina unique, what Chianti Classico terroir means and the modern marketing challenges for Chianti Classico producers.

Monty Waldin: Giuseppe, why is this terroir so special?

Giuseppe Mazzocolin: It is the idealization of this specific place. This is the border of Fèlsina and also the [far southern] border of Chianti Classico.

Is this where Chianti Classico ends?

This border, inside the estate, separates two denominations [between Chianti Classico and Chianti Colli Senesi]. The border was established in 1924, when it was necessary to distinguish the regional area of Chianti Classico from the rest of the other areas of Chianti. There's absolutely not only an administrative border, but also a geological border.

Basically Chianti Classico has a better soil for growing high quality grapes than Chianti on the other side?

Here there are two worlds. This is Chianti [Classico], absolutely Chianti [Classico]. We are very stony, very calcareous. In the other area [to the south across where the border where Chianti Classico ends and Chianti Colli Senesi or “Chianti from the hills of Siena’ begins] we have heavy clay [Chianti, but not Chianti Classico].

The clay!

Clay and sand, and cultivation is totally different. The [Chianti Colli Senesi, but not Chianti Classico] area is connected to the wheat. This is the border, wine and wheat, but we are inside this contest. That's the reason why there are two different varieties of Sangiovese. Because here [Chianti Classico] the Sangiovese is the noble Chianti. The elegant Chianti. The aristocracy! On the other side [Chianti Colli Senesi, but not Chianti Classico], Sangiovese is looking more in the direction of Brunello [di Montalcino, a 100% Sangiovese red wine made 30 miles/50 kilometres]. More intensity, more structure. It has an elegant style, a finesse, it’s a Sangiovese with longevity and potentiality. Rancia [a single vineyard Chianti Classico at 400-420 metres on limetone soil bottled separately by Fèlsina] that we see there, the house, and Fontalloro [another single vineyard wine which, because it straddles the border between Chianti Classico and Chianti Colli Senesi can only be bottled as an IGT Toscana Rosso or ‘red wine from Tuscany’] are connected to this totally different kind of soil.

I believe you're saying that the Sangiovese red wine grown on this [Chianti Classico] side is more like a ballerina and the Sangiovese grown on this [Chianti, not Classico] side is more like a bodybuilder.

Absolutely!

How old are these soils? Are they thousands of years old? Millions of years old?

Millions of years, probably five, six million years old.

The vineyards at Fattoria di Fèlsina photographed by Monty Waldin

This area used to be underwater, is that correct?

Underwater! The big story of Italy is that it started when everything was under the sea. When the two plates, Africa and Europe were pushing [Africa pushing north and up into mainland Europe], there was a great immersion of soils. The Apennine Mountains were developed and are part of Italy's story. Italy is down in the hills and the mountains. This great nation was created and this is the unique story of Italy. It is a story of differences. We also have stories of differences in Chianti. We have differences in Italy, millions of differences and unique, specific clues for different kinds of productions [wine styles], and also in the estate [of Fèlsina], we enjoy these differences. Because here we have 11 vineyards that are all with houses that date back to the Middle Ages. Each vineyard has its own identity.

In the old days how was the land divided up among the people who lived in these houses?

Crop sharing. When you pointed to that house there, the people left that house in 1956, because of the big frost. That separates the worlds. The Middle Ages before, and modernity to now.

The frost killed lots of olive trees and lots of vines. It was a real crisis in agriculture.

Absolutely, because people were living off the olive oil production, not wine. Wine was a local production [to be bartered locally in exchange for say eggs, milk, wool etc]. It was not an industry [meaning wine for export to international markets].

Basically, people grew wine to drink in their little farmhouses but they lived by selling oil from the olives. We could never imagine that Chianti now is a world famous wine, and only a few years ago it was totally unknown. What has changed for the better since that period? Has the modernist Chianti been an economic success story? Have we lost some of the traditions here? Where is the dividing line between tradition and modernity?

It's a big question. I remember the people living in these houses when they were younger. They had a great capacity to communicate about the past. I remember that these people were able to do everything. To work in the vineyards, to work the soil. With their capacity to be in the world and to graft a vineyard with incredible wisdom. People were really a part of this place. We lost such a great capital of humanity and knowledge, but in any case, it was necessary to follow another direction. These farmers became workers. Step by step they were substituted by new generations, with not the same capacities, of course. In any case, it was necessary to change. Now we have a modern wine industry. We produce wine [for both national international markets]. Before it was only a local production [for local consumption only].

Is it still possible to preserve those traditions and make big volumes of Chianti, or Chianti Classico? Describe a Chianti Classico wine that you feel has that sense of noble tradition in it. Is it in the taste? Is it the texture of the wine? What is it that would make a Chianti really traditional but modernist?

A good way is to conceive that the passion for Sangiovese of our old farmers is very much in relation to the way that we now perceive Sangiovese. With the modern style, with the modern vinification, but always connected with this uniqueness that is coming from the acidity, the tannins, the need to go back to the glass [a wine to light refreshing wine to sip over a meal, conversation, game of cards]. The memory of sitting and playing cards with the old farmers in the osteria [local eatery]. That kind of Sangiovese is still alive; it is still in our story.

You're saying it’s a wine that’s not heavily oaky. It's a wine that when you're playing cards at the local bar and you have a little sip, it doesn't knock you out.

It has a rustic ramification [meaning a wine with noble peasant origins], but sometimes it’s possible to find very good wine. I remember because I shared that kind of Chianti in the past. When I find this freshness again, especially in a young Chianti, I enjoy it very much because I feel the continuity [from the past when Sangiovese-based red wine like Chianti was often made to taste softer and easier-drinking by having to add some white wine grapes to it]. I perceive the continuity from the past into the present. Of course now when we have longevity, a wine that can age, because of the integrity of Sangiovese [meaning wine-growing methods such as knowing when to pick Sangiovese at perfect ripeness now allow much softer 100% Sangiovese wines to be made with no need of having to be softened by the addition of white grapes like Trebbiano and Malvasia, or very soft red grapes like Canaiolo]. Not a Canaiolo, a Trebbiano nor a Malvasia, now we understand that Sangiovese, by itself can be perceived and understood, because of this way of having a long life. Like in Brunello, that is [made 30 miles/50 kilometres away in the town of Montalcino] not so far away from here, when Biondi Santi decided to vinify this Brunello [starting in the 1880s], it was in relation to the same grape [Sangiovese, called ‘Bruenllo’ in Montalcino] of the same contest of Chianti. Because in that time it was used to produce Chianti Colli Senesi.

That was in the 1880s. Wasn't it with Brunello?

Exactly.

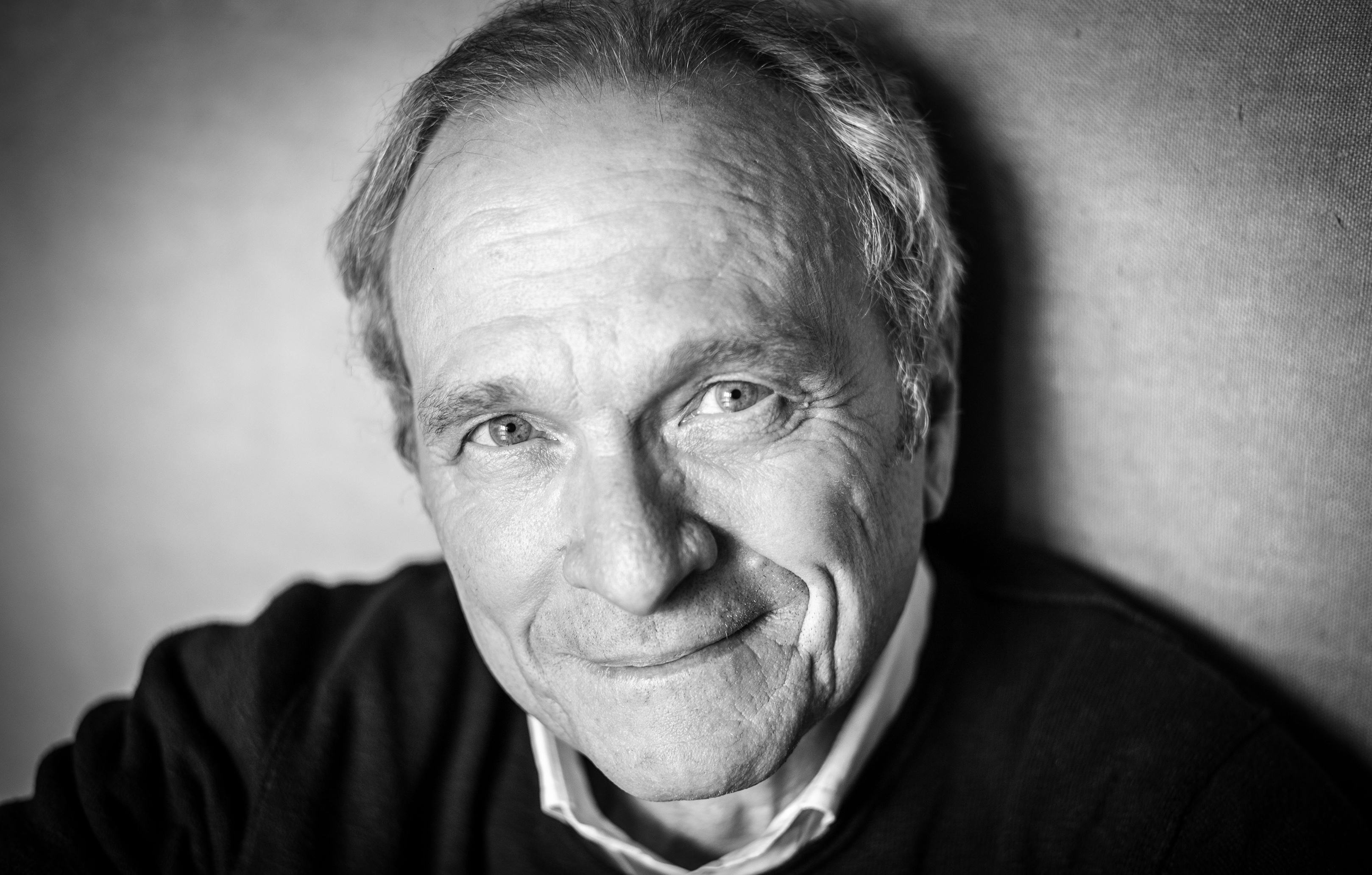

Giuseppe Mazzocolin of Fattoria di Fèlsina photographed by Monty Waldin

Are you saying a true Chianti is one that is based only on the local grape varieties? Obviously Sangiovese is the main one, but say, Malvasia Nera, Canaiolo and Trebbiano. Rather than say Merlot, or Cabernet from Bordeaux, or Syrah from the Rhône in France. Is it better to look for the wines that are only labelled Tuscan grapes?

I think so. I understand, I accept and I truly respect the different points of view and also the different needs of the producers. I'm not a guest. In any case I'm for the soil and the land. In the context of Fèlsina I think it's very important to maintain and to respect the past. We worked very hard to select the best Sangiovese. Also iteration of different vineyards [bottling wines from single vineyards separately to show differences in taste between wines from stony soils or wines from limestone soils], because we have an important capital of Sangiovese. We approach Sangiovese production not in an ideological way [a set recipe], but in relation to the work [how each vine plot is managed in its own way according to what soil it is on, how old it is, whch way it faces to the mid-day sun and so on].

When I hear you speak, you sound like someone from Burgundy, and you could substitute Chianti for Burgundy and Sangiovese for Pinot Noir. No Burgundian would ever think of putting Merlot, Cabernet, or Syrah in his Pinot Noir. You're saying that we have all the right tools here with our Sangiovese, why do we need to add French grapes? We have the love of the land, we have the knowledge of the people, we have a fantastic terroir - which you just explained - and, we have these grapes that work and that have worked for centuries.

I think we are growing. Everybody has his own experience. I'm not an Integralist. I think that for the passion of the Bordelaise [the winemakers of Bordeaux], of grapes from Bordeaux somebody can enjoy very much. Why not? No. Freedom, first of all. Freedom. Freedom. It is important to consider also the experience of different producers. I realize that there are very good areas like Panzano or Greve [two highly regarded Chianti Classico villages north of Fèlsina]. Why not? Sangiovese is something very unique. This is my point of view: Sangiovese is a great grape that gives freshness and pleasure, the freshness when it's young, and the pleasure of the maturation when it gets older. In some areas it is better to produce young Chianti. Some areas are much more mature. I'm ready to pay for a good fresh Chianti. It’s not the difference in that context. Because when I taste that freshness, fresh Sangiovese for me is a great experience. I'm ready to pay for that. I can enjoy that. Not Chianti...

Not a "whatever" Chianti.

Yes.

How old is Fèlsina? When was it first inhabited and when were the vineyards first planted? When did you arrive here?

First, this is a traditional farm with a lot of crop sharing. For many centuries, crop sharing was the way to approach, and to organize the agriculture [crop sharing was prevalent in Tuscany whereby farmers grew various crops, typically wine, olives, and grains and gave a percentage of the crops each year as rent to the person who owned the farmland]. Modernity came when my father-in-law bought the estate of Domenico Pozzali in 1966. I think that because of my wife, I started to be connected with this beautiful place. I was married in the church there, the one with the blue façade. That's the church!

What was the name of the people that gave this land its first individuality and cultural identity?

I think the Etruscan people were the first.

The Etruscans?

Yes, the name Fèlsina is an Etruscan name.

When were the Etruscans here?

Six centuries before Christ, six, seven centuries before Christ. It was the moment of the Roman people, then Christianity.

Was the architecture here influenced by the Florentines?

I think that was an influence, yes. It's important to understand that it's impossible to give a date. The story of this land is in relation to different people and different moments in the history of Tuscany and Italy.

It's a constant evolution.

Yes. It's important for me to perceive the past. I always say, if you want to come to [the nearby city of] Siena [as a tourist], okay. Be in relation with the past, past is always present [really understanding what happened in the past is a good way of understanding our present]. It's impossible to separate what is part of ourselves.

You are quite a philosopher. You studied philosophy, you taught philosophy. Was it a big shock for you to become a farmer?

When you study you are not in relation to the production [learning how to make wine is one thing, the reality of actually making it is different]. It was a shock to become part of an economical project [meaning if you forget to treat winemaking as a business, and think of it as a hobby you will go out of business]. The reality was evident. You have to sell, you have to produce and find the market. It was an important moment.

How did you do that? Your brand is very respected, it's a premium brand. How did you manage to convince people that your Chianti Classico was worth paying really good money for?

First, it was my father-in-law. He was a business manager in different areas. He was determined to work for this estate and grow this estate. First of all, it was him. I have great gratitude for him. He encouraged my work, my job. Secondly, it was the relationships, the good relations with the old farmers who were very great teachers. Their wisdom was absolutely important for my development. Thirdly, it was the work and the choice of Franco Bernabei.

He was your consultant winemaker?

Absolutely. He did a lot.

What did he do to make your wines taste so great?

Because of the different vineyards, we started to produce two and two plants and propagate [the best Sangiovese vine cuttings from the old farmers]. His contribution was absolutely the determinant. Because the microvinification gave us the opportunity to understand where to grow, which kind of vineyard, which kind of grape is chosen to become a model of our way to perceive the future of this estate [making trial wines from the various different Sangiovese cuttings the old farmers had allowed Fèlsina to find out which Sangiovese cuttings gave wine with the best aromas, the best flavours, the smoothest mouthfeel, the best ageability and so on and on which soils each cutting would work best.].

Microvinification is the process of discovering which soils produce the best quality?

Exactly, we realized that in this border land there were great opportunities to maintain and respect differences and learn more and more about Sangiovese. It was not easy in the beginning. People were not easily convinced that it was possible to produce Chianti without [having to add in] Canaiolo, Malvasia or Trebbiano [as softeners]. It was an important moment, to leave something in its past and look to the future. To receive from the market, the confirmation of our choice, oriented to the Sangiovese 100%. [Having made this research the wines then gained market acceptance, so they are happy]

Would you describe your Chianti as a modernist Chianti, or a modernist Chianti respecting the best of the old traditions and ignoring the worst of the old traditions? Which was for example, putting your white wine into your red wine. Which was allowed, was it?

I'm not against the old ways of approaching Chianti - the blend [a red wine made with a percentage of white wine grapes]. It's an idea to accept an everyday wine; but today we have to give value to the best grape inherited from the past, which is Sangiovese [with no need od any white grapes]. I think that if we are to guarantee the great capacity of Sangiovese to be versatile, fresh for a young wine where possible [everyday Chianti made from Sangiovese which can be drunk soon after it is bottles] - and matured Sangiovese to age and grow in the cellar [a richer, deeper Sangiovese aged in wooden barrels or larger vats and made to age in the bottle for drinking several years later]. It's a great experience to see both these orientations of Sangiovese. We are modern, but we also look to the past.

Sangiovese is a wine that responds well to be aged in wood. There are two choices, either larger vats made of Slavonian oak barrels or the smaller French barrels. Where do you stand in that great oak divide? Do you want oaky wines with a kind of French style, or very barely oaked wines that are more Tuscan in style?

I prefer it when Sangiovese is free to grow without a strong influence of oak. The oak, as far as the big larger vats, and the small ones, is an instrument to grow. It's not a condiment, it's not an ingredient. In my opinion, we always have to be moderated. Sangiovese needs care, a lot of care. I always say, this is my sentence: "never too much." Never too many plants per hectare, never too many bunches per plant. Never too much obstruction during the vinification, because Sangiovese is giving, but there's a limit. Never too much time to stay in the cellar, and never too much pretense for a wine that its own secret is in the balance. This ceremony that we can find in a bottle after ten, fifteen years is kind of mystery. It is not a problem. Of course there are, especially when there is a good harmony we see that a wine is destined to have a great longevity.

When you started making some of these changes, how did your fellow Chianti Classico producers view you? Did they think you were a little bit crazy? Or did they think, maybe he has some good ideas? Or let's wait and see, see if he makes a fool of himself or if it's a success, maybe we can copy what he's doing?

It's not very easy. Because there was a modern way to approach Sangiovese together with something else, another, a different grape from the tradition. That's the reason why there's the so called Tuscan...

Super Tuscan.

Super Tuscan.

Monty Waldin and Giuseppe Mazzocolin discussing the terroir of Fattoria di Fèlsina

That Super Tuscan means a Sangiovese blended with French varietals.

Fontalloro was the best way to officialize our 100% Sangiovese. The Rancia followed in the same direction. Together with my family, I was leading this passage, this evolution in a positive way. Not without a polemic approach.

You're just doing your own thing, and you believed it worked, and it tasted nice, and you thought, okay.

Exactly! Of course the idea was to maintain, to respect the story of Chianti Classico. Which for me is important, because it is the way to stay together in this area and to be responsible.

Did people think you were a little bit old fashioned?

I think that the best way to see and to watch the future is to be conservative. [Respect the best local traditions which have proved positive, adjust those traditions which need adjusting] Conservative means that it's not symmetry way to consider life. There's a movement, there's a way to go [being conservative, and respecting tradition does not mean you simply stand still]. I don't think that Burgundy reason is not so far to this way to conceive the past and the future [Burgundy has been making its red wines for a thousand years from the same grape, in their case Pinot Noir, and their story is one of slow, steady, incremental evolution so the wines get better but still retain their strong sense of place, identity, sense of history].

You mean they have 100% Pinot Noir reds, and you talk about 100% Sangiovese reds?

I’m very close to this idea, but I am not against the people, the producers, that want to use different varietal grapes. I'm open minded. Absolutely, open minded. What is important to consider is the landscape in its totality, not only wine, please. There's another important product in this privileged place, area of Chianti Classico, there's a wonderful production of olive oil. Because of it we are responsible for the production of olive oil in Italy—in its entirety, our country.

You're saying that Tuscan olive oil is among the best?

It's really very good, because its well done. When we give in Napoleon, Sicily, in Calabria, in all our regions the opportunity to produce in the right way, the quality is growing everywhere. There's no place that was…it’s impossible to not have a good olive oil in Italy. That's the reason its time for me, after the wine [having stepped back a bit from the day-to-day in terms of winemaking at Fèlsina], to be 100% dedicated to olive oil. It's an incredible chapter that is waiting to be written.

In the old days the people living on your farm, thrived on olive oil. It was a very important part of their diet, along of course with wine and grain, which you also have here. This idea of a mixed farm. How important is that to you to preserve these traditions? Not just with wine, but olive oil, and other crops. Will you be making bread next time I come and see you?

It's part of life. Don't forget in the past the farmers here, wanted to be paid in olive oil, not in money. Olive oil is much more important than any kind of money you can give, because they know what they have. They know because they were there to harvest the olives. They know which kind of care they dedicated to this product. Its time to value the work because of this connection. That's for me the subject. It's not enough to say that we produce. It's important to me the way we produce and the quality of the life—the people. That's my important subject. [Making a product which is absolutely bound to local tradition and local knowledge makes for strong communities and higher quality produce we can all enjoy]

Do you think sometimes, we take wine for granted? We're a little blasé about wine. You talk about people not respecting olive oil, do you think sometimes consumers don't respect how much work goes into wine and how risky it is? That's why it does cost. In order to get a good bottle of wine, you've got to pay a decent amount of money.

I will tell you my point of view, agriculture is one. We can produce a good beer, a good whiskey, everything that is coming from the soil, the ground is part of a united concept. Wine is a privilege to represent the best of our agriculture. We need bread and we need olive oil. Especially in this place. Its time to consider that we have to give value. First of all, in our mind, in our heart, to reach and conquer the objective, the economical return that we expect to have. I told you before that the price of wheat is still the same in 36 years. I cannot accept that. Also in the market you find manipulated olive oils, which is the majority of the olive oil we find in the market, that can cost three to four euros for a liter. When we know here that no less than fifty euros for a liter is possible [to achieve for the very best oils]. No less than fifty euros, and so for other producers. It's time to have a reason to guarantee the real economy. That's economy. Its a cultural approach, but it is a must in terms of numbers. I told you, when the last small producer of olive oil will be ready to have a return [to be economically sustainable making small amounts of oil like an artisan who is rewarded for his/her quality, and dedication to his/her craft/land/local traditions], in terms of economy, I think my work will be finished. Only in that case. It's full time and needs some centuries, but it's my real dream.

You've seen a lot of changes in the market’s perception of Chianti Classico. What changes have you seen in your 30 years? How is Chianti viewed by the market and how do people respect it as a product?

When I started, Chianti was a wine that was impossible to sell. It was much easier to sell a red wine from Friuli than a red wine from Chianti. You can imagine. It was a negative idea, a negative way to perceive it. It was very hard work, very hard work indeed. Sometimes there were not good vinifications [lack of attention to detail during the winemaking leading to vinegary-tasting wine] at the time when I started. They were rustic wines.

When you say it was hard work to sell, what has made the selling easier? What did you do and what did Chianti producers do to convince the market, "Actually we make a really good wine"?

Good acidity, good tannins, well integrated together. That’s the secret of our wines. Italian wines, not only Chianti.

You're saying that before Chianti was a bit rustic, a bit difficult to drink, a bit tough?

Yes.

How did you achieve that? What were you doing? Was it all about the winemaking?

Together with food, it was important to demonstrate the vocation of these wines was absolutely in relation to food. The quality Italian food, when it was well done, when we have good cuisine it's a great pleasure. It’s a good combination with these kind of wines.

What were you doing in the vineyards to avoid having wines that tasted a bit tough and leathery?

It was important to work in the vineyards and see the vineyards growing. You cannot create in a second, the quality of Sangiovese you expect to have. Now because of the work that was done in the vineyards, massale selection …

Working with grapes that produce good flavors?

Good flavors. When we identify the best clones [the heritage vine cuttings mentioned above which would have been selected over hundreds of years by the farmer-peasants, eliminating vines which produce poor wine, keeping only those which produce healthy, clean, ripe, well-coloured, well-flavoured grapes] we received from the past, we were ready to start and vinify a new category of Sangiovese. It was the work that was done in the vineyard.

How important was picking the grapes ripe, rather than a little bit under ripe, or a little bit over ripe? How important was knowing when to pick them at the right time?

In the middle, yes. I think that is important to guarantee the ripeness, but not for a long time.

Not overripe?

No, no, no. There's always a limit.

You want your Sangiovese to give you a crunchy, crisp, fresh finish and not a jammy one.

Exactly.

How do you do that? What do you do in the vines. What bit of the farming helps you get Sangiovese groups ...

Less production. Honestly, that's the secret.

You have to lower your yields and sacrifice money.

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. That's the secret, and then to know each vineyard by itself.

Should we say treat ...

Its time to harvest the grapes from the vineyards, dedicated for Chianti Classico. Which is very representative of lot of Sangiovese. When the so called normal [‘normale’ in Italian, usually a lightish wine with no oak ageing made to be drunk young], or the basic Chianti Classico, is working that is giving us something unique. I love the normal [‘normale’] Chianti Classico because of its capacity to give an interpretation of Felsina in it's totality. [In other words his entry-level Chianti Classico is and should be the starting point for anyone wanting to get to know his vines.]

You're saying your basic Chianti, no real wood in ...

It must be good every year. That's the most important thing. Of course we have to distinguish what is Rancia and what is Fontalloro. Because it's easy they are there and they are their own vocation. The Chianti Classico [normale] has the blend of different vineyards and different Sangiovese is the secret of this estate. It's an open secret. [meaning the wine which represents best all the other Sangiovese-based wines Fèlsina makes]

Knowing every single plot of Sangiovese, knowing when to pick each one according to it's needs and how to ferment it, transfer it into wine according to its ... How many years did it take you to really understand your vineyard? You have a very big vineyard, it wasn't something that happened in five years.

It was necessary to wait. We started with 3,000 bottles of Fontalloro and more and less the same of Rancia. It was necessary to distinguish and know step by step. Also the evolution in the bottle of this wine. We started to vinify 100% Sangiovese with Rancia, and Fontalloro, and Chianti Classico in 1983.

When did you start? '83.

1983. I started work with [respected consultant winemaker Franco] Bernabei in 1982.

How much is your production of Fontalloro now?

40,000, 45,000 bottles. Rancia a little bit more. Never big quantities. It's not possible to produce more. The parcels of the vineyards are visible and declared.

Chianti is a very confusing term for many people. There's Chianti, Chianti Classico, Chianti Rufina. How do you make it easy for people to understand what is special about Chianti Classico?

I understand it's not easy to communicate so many differences. Italy is made of differences, but I understand the problem. It's something that we iterated from the past, because of their so called brands that were used by industrial companies. When there was Chianti, Valpolicella, Bardolino, there were some big names to identify what was Italian. Now, there's another direction that we are going, where we are going. When it's becoming evident, the potentiality and the clear character of the single areas [meaning individual wines from individial single vineyards like Rancia, each with the own special character as opposed to wines made from a large number of disparate vineyards blended together to produce a homogeneous but less individualistic whole], then people become more knowledgeable. This is the step we have reached now. Now there is another step that is important to me. It is to identify the areas of production, together in relation to the wines. It's not enough to say, and have a departure from the denomination. It's time to have the relation also identified to the landscape, to the area. Chianti Classico has this great opportunity of course. I'm sure that also for other consorzios there's a future. Not only a future, but there will be a future because of the responsibility, this possibility of each producers to grow in this way.

You're saying that people are understanding that there is a difference in quality between Chianti Classico and normal or basic Chianti. Now you're saying that because there are various villages and soil types, and differences in the geology of Chianti Classico that we're now going to start seeing Chianti Classico from certain places.

Si [‘Yes’]. Our consumers have to grow in the way to be in relation with the landscape, and to understand that they can find a Chianti, Chianti Colli Senesi [Chianti from the Hills of Siena], or Chianti Colli Fiorentini [Chianti from the Hills of Florence], a good Chianti Classico, because of their own capacity to distinguish the character of the wine.

You're saying that the consumers will be able to notice that Chianti Classico is a step up from anything else with the name Chianti on it?

I think Chianti is the name that covers or protects all this area. We have to be able to understand and distinguish, case by case. I'm optimistic in that direction. Because there are some denominations in countries much bigger than our Chianti. I think it's time to give formation and to particularly encourage the new generation to approach with an open mind this area called Chianti.

I can see in your previous life you were a teacher. Thanks very much, it's been a great pleasure to talk to you.

Monty Waldin was the first wine writer to specialize in green issues. He is the author of multiple books, including The Organic Wine Guide (Thorsons, 1999); Biodynamic Wines (Mitchell Beazley, 2004); Wines of South America (Mitchell Beazley, 2003), winner of America’s prestigious James Beard Book Award; Discovering Wine Country: Bordeaux (2005) and Discovering Wine Country: Tuscany (2006), both Mitchell Beazley; and Château Monty (Portico, 2008). Monty has contributed on topics of organic and Biodynamic wine to Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Guide, Tom Stevenson’s Wine Report and he wrote the entries for Biodynamics and organics in The Oxford Companion to Wine (2015; 2006). He has also contributed to BBC radio and TV, numerous British newspapers and websites, as well as to wine, travel and environmental publications including Decanter, World of Fine Wine, The Ecologist, Star & Furrow (journal of the Biodynamic Agricultural Association, UK) and Biodynamics (journal of the Biodynamic Farming & Gardening Association, USA). His most recent books are Monty Waldin’s Best Biodynamic Wines (Floris, 2013) for wine drinkers, Biodynamic Gardening (Dorling Kindersley, 2014) for biodynamic home gardeners, and Biodynamic Wine (2016, Infinite Ideas Oxford), the comprehensive how-to guide for biodynamic wine-growers and students of biodynamic wine.

Buy Monty Waldin's detailed guide to the nuts-and-bolts of biodynamic wine-growing on Amazon.