“If you want to hear the most beautiful aria, you have to care for your diva. Grüner Veltliner is a diva. If you don’t treat it well, it’ll turn its back on you.” Austrian winemaker Bernhard Ott learned this lesson from years of coaxing incandescent performances from his sensitive star. When Veltliner is cosseted, it scales the registers of purity, tension, and finesse. When it’s not? Well, like a dull Tuesday night act in a bad club, it can be “very banal,” Ott almost sighs.

“Earlier, I would often hear ‘The vines have to suffer to give good quality.’ But that is not the case with Veltliner,” Ott asserts. “Veltliner can’t have any stress. If it does, it will taste like Sauvignon Blanc — green, sticky on the palate, no acidity, no finesse." Over time, Ott has come to understand that to make Veltliner sing, "the essentials are biodynamics, soils that are in good condition, and no monoculture." His farm is a paragon of this. With 30 bee colonies, 600 birdhouses, and trees in every vineyard, Ott is cultivating not vines but an entire environment. "If you think very long term, make sure the soil is healthy, and the vine feels comfortable there, the wine will be much purer, more taut, more elegant. It will also age much longer. Nothing that is produced under stress lasts. These wines will last 30, 40, 50 years. The oldest bottle in our cellar is from 1933. I’ve had some from ‘71 that are perfect now.”

Ott, 46, is the fourth generation of his family to live and farm in Feuersbrunn, in the heart of Wagram. His 40 hectares there and in Engabrunn, just over the regional border, in Kamptal, are 95% Grüner Veltliner. (He also grows a small amount of Riesling on primary rock sites better suited to that grape as well as the Austrian field blend known as Gemischter Satz). His vineyards, or Rieden, as they are called in Austria, are some of Grüner Veltliner's true grand crus — Rosenberg, Spiegel, and Stein are names to remember. They are home to Ott's oldest vines (the oldest planted in 1956) and are all on loess, the composite of wind-blown silt and sand cemented by calcium carbonate and compacted by time that is, in Ott's view, a requirement if Veltliner is to show its true self.

Ott, 46, is the fourth generation of his family to live and farm in Feuersbrunn, in the heart of Wagram. His 40 hectares there and in Engabrunn, just over the regional border, in Kamptal, are 95% Grüner Veltliner. (He also grows a small amount of Riesling on primary rock sites better suited to that grape as well as the Austrian field blend known as Gemischter Satz). His vineyards, or Rieden, as they are called in Austria, are some of Grüner Veltliner's true grand crus — Rosenberg, Spiegel, and Stein are names to remember. They are home to Ott's oldest vines (the oldest planted in 1956) and are all on loess, the composite of wind-blown silt and sand cemented by calcium carbonate and compacted by time that is, in Ott's view, a requirement if Veltliner is to show its true self.

(Photo, left: Bernhard Ott, courtesy Skurnik Wines)

Wagram takes its name from the old German word Wogenrain, meaning shore, as in river's edge. “You have to picture it like this,” explains Ott. “We’re on the Danube plain. The Danube is very wide, really an enormous river. Then comes the alluvial forest, many grain fields and then the vineyard terraces.” The terraces are the work of Burgundian monks, who cut broad steps from the thick layer of loess — up to 90 feet deep in some sections — starting in the 10th century. The monks recognized that Wagram's climate, marked by warm sunny days and sharply cooler nights, is exceptional for grape growing. This has not fundamentally changed in a thousand years, even now, in an era of rising temperatures, erratic weather, and forshortened harvest times.

For much of their existence, these vineyards would have been planted for Gemischter Satz as a hedge against the failure of any one variety. Now they are devoted to Grüner Veltliner. For a long time, Veltliner was a grape in need of a good paternity test. It was known to be a natural crossing between Traminer and a second grape, whose identity stubbornly eluded identification until 2000. That year, a combination of genetic testing and blind luck lead researchers to a single abandoned vine — thought to be some 500 years old — in the town of Sankt Georgen, east of Vienna. Cuttings from that vine were used to propagate a small vineyard and the variety now carries the name of the town. (Bizarrely, in 2011, a vandal hacked up the original St. Georgen vine, but survived this assault.)

Today, Grüner Veltliner is Austria’s vinous calling card. Even with the rise in quality and popularity of native reds Blaufränkisch, Zweigelt, and St. Laurent, fully one-third of all Austrian wine is made from this one white grape.  This circumstance is the product of Austria’s geology, geography, climate, cuisine, culture, and, rather specifically, the Lenz Moser vine training system. This trellising style was introduced to Austria in the 1920s by a viticultural scientist who noticed vines trained higher off the ground and planted at lower densities were less prone to frost damage and easier to work by machine. Grüner Veltliner responded well to this type of training and the grape quickly proliferated. By the 1950s, the Lenz Moser "high culture" system had been widely adopted, and Veltliner production amped up accordingly. However, attentive producers found that the system's high leaf canopy shades fruit, diminishing quality, and their adherence to hand harvest negated the need for machine work from the start. Ott trains his vines on Guyot, prefering medium cordon and canopy heights.

This circumstance is the product of Austria’s geology, geography, climate, cuisine, culture, and, rather specifically, the Lenz Moser vine training system. This trellising style was introduced to Austria in the 1920s by a viticultural scientist who noticed vines trained higher off the ground and planted at lower densities were less prone to frost damage and easier to work by machine. Grüner Veltliner responded well to this type of training and the grape quickly proliferated. By the 1950s, the Lenz Moser "high culture" system had been widely adopted, and Veltliner production amped up accordingly. However, attentive producers found that the system's high leaf canopy shades fruit, diminishing quality, and their adherence to hand harvest negated the need for machine work from the start. Ott trains his vines on Guyot, prefering medium cordon and canopy heights.

(Photo, right: Grüner Veltliner grapes, courtesy Austrian Wine Marketing GmbH)

The 1980s were a time of exceptionally good vintages for Austrian wine, but few people remember this now because of what came to be known as the Glykolwein-Skandal. In 1985, news broke that a handful of Austrian bulk wine producers had been adding diethylene glycol, an ingredient in antifreeze, to their wines. It was a cheap, short-sighted, and reckless way of boosting sweetness and body in lean vintages — and poisoning the market for Austrian wine for at least a decade.

It’s important to pause here and note that Austria, though a small country with only a fraction of its land suited to wine growing, is now a global leader in meaningfully responsible viticulture and minimalist winemaking. In a recent report, biodynamic wine expert Monty Waldin found that more than 10% of Austria’s vineyards are organic or biodynamic versus the worldwide average of 4.5%. Moreover, Waldin notes that Austria has a remarkably high percentage of wine estates with full Demeter certification, one of the strictest standards in biodynamics. One way to view Austria’s exceptional strength in this area is as a long, hard pendulum swing away from the scandal.

By the turn of this century, the reputation of Austrian wine had recovered sufficiently for influential somms in the U.S. to reconsider them, especially Grüner Veltliner. They seized on the wine’s peppery brightness, tingling acidity, mineral intensity, and clean textures that make it so versatile at the table. I recall the thrill of tasting an F.X. Pichler Veltliner paired with an arresting licorice soup created by chef Paul Liebrandt when he cooked at Atlas in Manhattan in the early 2000s. It was my first experience of how wine could alchemize food. Today, the profusion of native grapes pouring in from virtually all parts of Europe has pushed Grüner Veltliner out of the spotlight, but it remains a superb choice for lovers of precise, vibrant wines of place and character.

There are few people more symbiotically entwined with Grüner Veltliner than Bernhard “Ich bin ein Veltliner” Ott. His gregarious nature gives way to quiet, earnest conviction when the topic turns to the interplay of grape, biodynamics, and loess. Ott has been making wine for 25 years, virtually all of that time on his family’s vineyards in the cool Wagram hills. He left home to study viticulture and work around the world, “but at 21 there aren’t many jobs you can do,” he says, so he went back to Wagram. “At the beginning, I was a little unhappy because I wanted to do something else. But my father said, ‘You have to start early. If you’re a baker, you can bake a hundred loaves a day until you get them perfect. But as a winemaker, you only get one chance each year. And it’s different every year. So, the sooner you start, the better you’ll become.’ I did that and in ‘93, my father handed the estate over to me.” Ott confesses: “Today I’m a little sad because my father worked with wooden casks, but I stopped that — though now I’ve started buying some. My father always worked with whole cluster, but I destemmed. When you’re young, you want to try new things, not do them the way your father did. But now, after 20 years, I do things exactly as he did.”

(Photo, left: Vineyards of Wagram, courtesy Austrian Wine Marketing GmbH)

“Where we are in Wagram,” Ott explains, “the loess soil is very fine, compacted sediment. In the last Ice Age, there were temperature swings, and every time the rocks warmed up, fissures formed, and water seeped in. Then it got cold, the water froze and expanded. This friction — also from the passage of the glaciers — created sediment that became the loess soils. The advantage is that the Alps near us are known as the Kalkalpen [limestone Alps], so our loess has extremely high limestone content. We can, in some cases, use the same rootstocks as in Burgundy, because the limestone content here is so high.” Loess also has extraordinary water-absorption capacity: up to 400 liters of water per cubic meter of soil, according to Ott. Veltliner's low tolerance for hydric stress means “this is why loess equals Grüner Veltliner. Loess is Veltliner, primary rock is Riesling. I believe that is very, very important to know."

Since Ott equates himself with Veltliner (his tagline is "Ich bin ein Veltliner") and Veltliner with loess, it seems fair to take this a step further and say Ott is loess. It's appropriate, then, that this is an area of intensive investment for him. Compost — for him, a rich mix of cow manure, straw, apricot tree prunings (Ott and his family also maintain 3 hectares of apricot orchards), and biodynamic preparations, or "preps" — is essential to this, buildling the soil with an eye to its present and future health.

Preps are something many producers talk about, as if by sprinkling them here and there they can will their vines to vitality (or sell their wines in the increasingly popular biodynamic “category”). For Ott, the correct application of preps is elemental to biodynamics, and biodynamics is integral to his farming. He views were catalyzed by late American professor of biodynamic viticulture Dr. Andrew Lorand and by long consideration of the state of wine. “Right now we have a development,” he explains, “Wines are either technical or made by hand. For me the greatest danger is that wine will become too technical. I could already see this development in 2006. I asked myself, ‘What distinguishes me from my neighbors? What distinguishes me from my colleagues? Now we all buy the same fertilizer, the same sprays, the same yeasts, the same technology. What’s the difference?”

The answer lies with Austria’s greatest contribution to wine and, it may turn out, the survival of the planet: native son and father of biodynamics, Rudolf Steiner. Ott could not help be influenced by the proximity (roughly 20 miles) of the Ott vineyards to the place where Steiner’s parents lived. “We are in the exact climatic zone where biodynamics began,” Ott points out. Working from this awareness, he and a group of friends founded a biodynamic certifying body they called RESPEKT, born from “the desire to find a way out of uniformity.” He explains, “We all wanted to break out of this system of fear. You go to school, you study, you’re made fearful. You learn about illnesses and negative things that could possibly happen. And to combat all this, there’s always a solution from chemistry or technology. But that influences a person’s character. It took 15 to 20 years for me to free myself from this fear. Biodynamics was the key to this.” Today RESPEKT includes 22 members in Austria, Germany, Italy, and Hungary, among them such doyens of far-sighted, responsible farming as Clemens Busch in the Mosel, Hansjörg Rebholz in the Pfalz, Franz Weninger in Burgenland, and Johannes Hirsch in Kamptal.

Ott notes that Steiner’s direct influence should be seen as a springboard rather than a cage. “Of course, it’s exciting to see where the biodynamic preparations were discovered, where the ideas had their origins and Steiner began his work. Nevertheless, one has to realize we’ve evolved further,” Ott says. “We don’t see things dogmatically, rather we work in the present with respect for history, for the rhythms of nature.” He is most passionate about aligning his efforts with nature’s flow. He explains this in terms of lunar cycles: “The full moon is expansion, growth. If I want to do something that brings strength, I do it during the full moon. If I do it during the new moon, it takes me twice the effort.”

Ott notes that Steiner’s direct influence should be seen as a springboard rather than a cage. “Of course, it’s exciting to see where the biodynamic preparations were discovered, where the ideas had their origins and Steiner began his work. Nevertheless, one has to realize we’ve evolved further,” Ott says. “We don’t see things dogmatically, rather we work in the present with respect for history, for the rhythms of nature.” He is most passionate about aligning his efforts with nature’s flow. He explains this in terms of lunar cycles: “The full moon is expansion, growth. If I want to do something that brings strength, I do it during the full moon. If I do it during the new moon, it takes me twice the effort.”

As an acolyte of Dr. Lorand, Ott came to view the plant as a whole, and to appreciate biodynamic preparations for their therapeutic properties. Ott believes preps are only useful when applied in accordance with nature’s rhythms “for growth and also for quiet phases, where nature pulls back, ripens.” Two key preps go by the numbers 500 and 501. “500 stands for growth,” Ott explains: “It’s dynamized and sprayed before the full moon. Although the vine is already nervous because it’s growing, with 500, you can give the vine a little push. We spray 500 on the ground, ideally when it has rained a bit. It enters the soil and promotes very fine root growth. You can see this very clearly if you look at a vine that has been treated biodynamically for five years. If you pull it up you find many, many very fine roots. If you compare it with a conventionally grown vine, you find very thick roots that are very shallow.” 500's counterpart 501, “based on silica, which dries things. It is sprayed on the vine tendrils, and is used to slow vine growth, to bring about ripeness. The tendrils are very sensitive. Silica gives the vine a signal, ‘There is someone who wants to slow me down. I’d better not grow any more, I’d better ripen.’ This is what we’ve been doing before the new moon.”

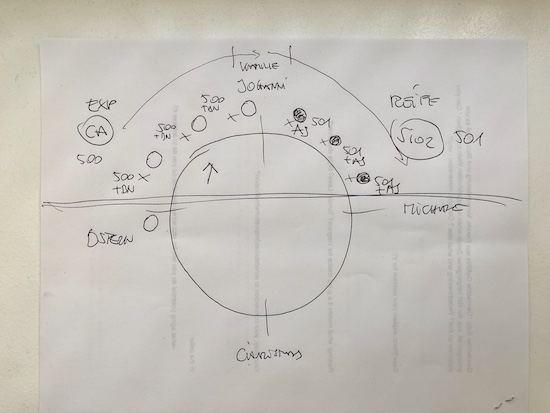

Ott gets more specific. He pulls a pen from his pocket and begins to sketch a diagram, to give “a brief explanation of biodynamic practices as I see them.”  “Easter is the first Sunday after the full moon, after the start of spring. Then we have one, two, three full moons until Johanni [roughly the summer solstice]. That’s when we want the vines to grow: expansion. That’s where we want ripeness. After that, we have three new moons. Always, shortly before the full moon, and shortly before the new moon, we apply 500 and 501. The sun rises to the point of the longest day and then recedes. And here the balance is the length of day and night. That is when we prepare a tea, we have three different teas: nettle, camomile, and horsetail. Horsetail is very, very rich in silica. So we spray 500 plus the nettle tea. Nettle is sprayed on the ground like 500. It works to inhibit the fungus and keep the vine roots healthy. Then we spray the horsetail tea. But in between, we spray the camomile tea. You have to imagine that at first we just want the vines to grow, grow, grow. And then they have to develop in a completely different direction, toward ripeness. And just at the moment when they have to make that change, we spray the camomile tea to calm them.”

“Easter is the first Sunday after the full moon, after the start of spring. Then we have one, two, three full moons until Johanni [roughly the summer solstice]. That’s when we want the vines to grow: expansion. That’s where we want ripeness. After that, we have three new moons. Always, shortly before the full moon, and shortly before the new moon, we apply 500 and 501. The sun rises to the point of the longest day and then recedes. And here the balance is the length of day and night. That is when we prepare a tea, we have three different teas: nettle, camomile, and horsetail. Horsetail is very, very rich in silica. So we spray 500 plus the nettle tea. Nettle is sprayed on the ground like 500. It works to inhibit the fungus and keep the vine roots healthy. Then we spray the horsetail tea. But in between, we spray the camomile tea. You have to imagine that at first we just want the vines to grow, grow, grow. And then they have to develop in a completely different direction, toward ripeness. And just at the moment when they have to make that change, we spray the camomile tea to calm them.”

In the cellar, Ott works with an eye to giving long life to his wines. For the single vineyards, Ott does no destemming, only crushing, with 20 hours skin contact. Maceration times depend on the vintage, the vineyard, and the quality of fruit. Ott “browns” the juice, an oxygenating technique that precipitates out elements that could cause the wine to oxidize prematurely in the bottle. He then racks to stainless steel tanks for spontaneous fermentation without temperature control. He uses minimal added SO2 and keeps his cellar very cold to prevent the wines from going through malolactic fermentation, which would plane off some of the desirable edges from the finished wines.  Ott’s single vineyard wines stay on the full lees into the summer, before being racked and bottled. Ott also makes vineyard blends like “Am Berg,” “Der Ott,” and "Fass 4, " which express a very personal interpretation of his chosen grape.

Ott’s single vineyard wines stay on the full lees into the summer, before being racked and bottled. Ott also makes vineyard blends like “Am Berg,” “Der Ott,” and "Fass 4, " which express a very personal interpretation of his chosen grape.

For a time, Ott sought to get closer to Veltliner's true nature by experimenting with qvevri, large earthenware vessels that were common to winemaking in the ancient world. Ott says he worked with qvevri because "I wanted to know how Veltliner would taste if I, as the winemaker, did nothing in the cellar. I’m very happy about it because it played a role in developing my style: That you don’t need yeast, but patience, that Veltliner’s style belongs to the grape itself.” Although he is certainly what can only be called a natural winemaker, he is a judicious one, who never looses site of his aims. “I have the feeling that in, let’s say, ‘raw wines,’ oxidation often destroys terroir. I am very, very open to these types of wine, but I fear oxidation destroys terroir. When I taste wine, then I want to taste where it’s from because that’s what makes the wine. But when we speak of a single variety like Veltliner, from a specific terroir, I want to taste that. Terroir is our most valuable good.”

At the end of the first week of October, Ott has just wrapped up harvest — "earlier than ever this year," he notes. "In summer-like temperatures, we harvested perfectly ripe grapes. Since we had already markedly reduced yields through crop thinning, we could harvest all the vineyards in just three weeks." Ott opted for whole cluster pressing for the entire harvest "to get the grapes into the press quickly and intact and in this way retain the great acid structure." In this way, Ott has given his diva yet another opportunity to sing in perfect harmony.

This interview was conducted in German and translated by the author.

Images courtesy of Skurnik Wines, Austrian Wine Marketing GmbH, Weingut Bernhard Ott, and the author.