In solidarity with the Global March for Science, which happened a few weeks ago, when hundreds of thousands of scientists and supporters rallied in Washington DC in addition to the other 600 marches around the globe, Grape Collective has decided to review the current state of science in wine.

Though the science of wine is a story infrequently told to consumers, the industry has come a long way in adopting rigorous science. Essentially, we have gotten down the basics: grapes can produce better wines under certain climatic conditions, and arguably using appropriate vinifying techniques can further enhance the quality of the wine. When taking customers into account, sales are up across the board, a country’s reputation may affect its reception, and new wines are given a shot through trustworthy recommendations. No matter which wine ends up in your glass, most toast to those health studies that suggest a glass a day will keep the doctor away. Given this body of knowledge, do we know enough?

Well, to answer that question, we have to know where we started: jug wine. The jug wine market was created by European immigrants, many of them Italians, who bought crates from the trains that pulled in from California. In the 1930s, August Sebastiani recalled visiting local wineries that bought grapes from his vineyard. “Some of them were terrible places,” he once said. “Dirt, mold, rusty pipes; they couldn't have cared less about the wine.”

We have come a long way. Scientific research addresses may industry problems: grapevine disease, viticulture under strenuous weather condition, incomplete or slow-moving fermentations, analyzing soil compositions, classifying unknown grape varietals, etc. Science, however, cannot offer recipes for making good wine. Winemaking is an art involving decisions about taste and style.

The funny thing about wine is that key factors in the winemaking process are always in flux. Climate change, shifting global demand, new vinification techniques, discovery of ancient grape varietals, and marketing innovations will transform the industry anew.

In the meantime, the United States is a mature market and consumers should demand the most from its wine and grape professionals. And yet there is already a mountain of knowledge to be discovered. But, it is essential that the findings of research are communicated with everyday consumers. For example, in 2011, researchers published a review of wine and its health affects (the good and the bad, sorry!) in the American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, the most widely disseminated publication of the industry in English. Who in their right mind is going to sit around all day and read academic journals of wine? Further, recent research suggests that there is a clear divide in understanding between scientists and the general public. We need to do better in communicating wine science.

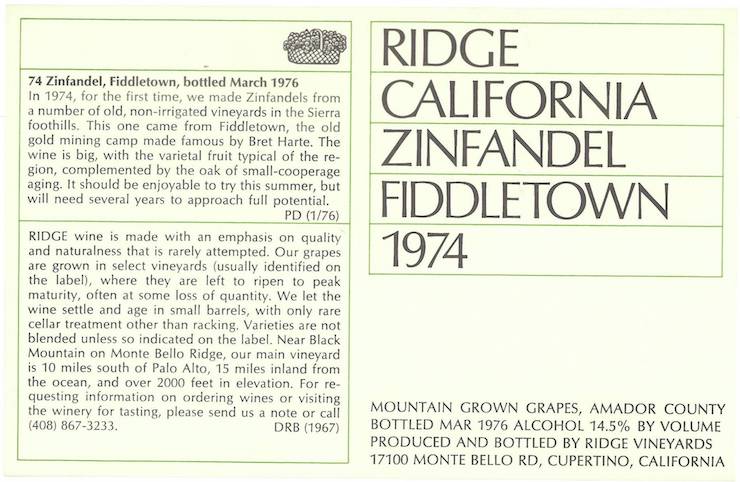

There are direct routes to customer engagement. Take for example Ridge, one of California’s prized producers. They deliver a detailed account of their winemaking process on every wine bottle:

Not every producer should have to comply with this strict requirement, but there is a growing need to regain a level of confidence between buyer and supplier. Recently, there was an infamous article published in The New York Times suggesting that we know basically nothing about what is in wine. That’s not exactly true.

If you seek out dependable distributors with principled producers, you will find great wine. Most important of all, if you ask the right questions before you drink the wine, you will be rewarded. Ultimately, science prevails and helps us make more informed decisions.

Here are some helpful links to get you started:

Wine folly:

http://winefolly.com/review/the-science-behind-great-wine/

UC Davis:

Research Journals:

http://winegrapes.tamu.edu/research/research-literature/viticulture-and-enology-research-journals/

In the spirit of science communication, below is some recent research that I conducted for a graduate class:

DISCOVERING WHAT MAKES A GREAT WINE EXPERIENCE: AN ANALYSIS UTILIZING PARTICIPATORY RANKING METHODOLOGY

RESEARCH QUESTION

The US is the largest wine-consuming nation in the world [1]. In 2015, 913 million gallons of wine were consumed, corresponding to 2.83 gallons of consumption per resident [2]. The estimated retail value of wine was $55.8 billion in 2015 [3]. Millennials, which now make up about one-third of consumers, have contributed to this growth [4].

Drinking wine has many implications beyond the glass. A myriad of research studies suggests drinking wine moderately can be beneficial to health [5]. On the other hand, drinking too much wine can lead to negative health consequences associated with alcoholism [5].

Above all, drinking wine has been a beloved part of social engagement for millennia. Going back to the 12th century, Omar Khayyám describes the essential role that wine has in living a good life:

“Drink wine. This is life eternal. This is all that youth will give you. It is the season for wine, roses and drunken friends. Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life."

― Omar Khayyám, The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám (1120 AD)

Currently, there is limited literature on the attitudes and perceptions of wine among new consumers. To fill the gap in the literature, the research question, What makes a great wine experience?, was explored utilizing participatory ranking methodology (PRM).

SAMPLE

Participants were chosen based on my social network. I called up some of my closest friends and asked if they were available to participate in a research study relating to wine. While the research topic drew a lot of attention, only six individuals were available for the pre-selected time.

Most of the participants were novice wine consumers. They did not know a lot about wine, yet they had some experience, ranging from more than three glasses per week to a few drinks per month.

Participants were made up of four females, two foreign-born nationals, five graduate students, and all were below the age of 30.

METHODS

On April 4, 2017, a single group of wine consumers in their mid-twenties were engaged in PRM, with aims of exploring the aforementioned research question. PRM was developed by Columbia University faculty and employs core principles from focus group methodology and participatory rural appraisal. The PRM recognizes study participants as key sources of valuable information in answering the research. Due to time constraints, only one focus group was conducted at my residence in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City.

As a friend, fellow student, and wine expert, I facilitated the PRM focus group, conferring the trust of the participants and increasing the confidence of honest responses and discussion. Prior to the PRM focus group, the facilitator clarified the research question, explained the format of the discussion, and assured participants’ personal information would remain confidential. The note-taker was introduced and her role was explained to the participants.

The focus group followed standard PRM process: pile, rank, and account. First, the scope of the research question was defined, responses were elicited from participants, objects were selected to represent the ideas, participants negotiated categories, and participants were prompted if necessary. Second, participants defined a continuum, placed objects in a ranking order, and adjusted positions of objects if necessary. Last, the ranking order was clarified and recorded.

During the PRM focus group, participants enjoyed wine and a light snack. There were four wines selected: Nardello Soave Classico, Michael Sullberg Chardonnay, Monte Bernardi Chianti Classico, and Sevilen Red Dry Wine (served in this order, from lightest to boldest, as is common practice). While the wines represent a range, the selection was not a complete representation of winemaking styles. The wine was meant to stimulate prior experience and not to be part of an observatory study. Finally, the wines were not identified until after the focus group was concluded, so that bias was not introduced.

RESULTS

The conversation during the focus group was lively and probing. Immediately, certain themes appeared in the conversation. The first themes were flavor and context: “I think that the level of sweetness to dryness matters to me. I’m rarely in the mood for a sweet but sometimes if it’s a hot day I’ll want a crisp one. So that’s a quality I look for in a wine. So it varies on my mood and what I’m eating and the weather”...“I always go for rose, it’s my go to in summer.” Shortly after, concerns about price strongly emerged, with statements like “I’m pretty price-sensitive,” “My go-to price range is about 10-12, I would never do more than 15 on a Monday night,” and “If I’m going out and there’s a really good glass of wine, I’ll pay $16.”

Another important topic of conversation was a trustworthy recommendation: “I think it also depends on the type of store I’m going into. If I’m going into the liquor store I usually go to, I know it’s not good so I’m going to get something standard,” and “Yeah, if someone can convince me by saying something then I’ll buy it.”

Food pairing with wine seemed very important to this focus group. “I think food always matters,” “I think the only time I have white wine is with seafood,” and “If I’m at home eating shitty pizza and watching a shitty movie, then I’m going to buy a shitty wine. But, if I make myself a nice meal then I’ll probably go for a nice wine.”

The country or region of where the wine comes from also seemed important to most focus group members. “Yes, I would never want a wine from India. I know I could get a good cheap wine from Chile, but Italy has more variability so a wine from Italy might be good or bad.”

On another note, there was confusion about the winemaking process. Specifically, there was confusion about the different vinification techniques and viticulture practices. The idea of organic or natural wine was not important to this focus group: “Fuck that, I never drink organic wine.” Ultimately, the grape was the most important aspect of winemaking: “I think the type of grape is important when choosing a wine.”

Lastly, a surprising aspect of the wine experience appeared: time and place, or situation. “Maybe, like it depends on if I’m alone or on a date. Actually, if I were wearing lipstick I might not drink it.” The participant was talking about the teeth-staining ability of wine. Other participants agreed with this notion.

After the discussion, the ideas and themes were represented using objects in the following order:

Table 1

|

Rank |

Idea |

Object |

|

1 |

Flavor |

Vase |

|

2 |

Context |

Japanese Coaster |

|

3 |

Price |

Wallet |

|

4 |

Food pairing |

Cookie |

|

5 |

Origin of wine |

Easter Egg |

|

6 |

Trustworthy recommendation |

Pen |

|

7 |

Grape |

Coca-Cola glass |

|

8 |

Staining teeth ability |

White plate |

The objects have little to no association with the wine. In most situations, the objects served as mere placeholders for the ideas in order to rank them.

DISCUSSION

The results were very insightful for this market segment. The focus group showed acute awareness of well-known aspects of making a great wine experience. Context was widely seen as one of the most important factors in having a great wine experience.

Participants of the focus group was very concerned with price. The majority of the sample were graduate students with tight budgets, which may have influenced economic access to higher priced wine. Nonetheless, the group was well aware of the competitive marketplace in the wine industry and the wide selection of bargain deals.

Most members of the focus group had narrow experience with wines of various styles coupled with no to little experience with high-quality wine. For this reason, the exact type of wine or style was not held in high regard by the participants.

Finally, group members admitted that they would consider purchasing a more expensive wine if they were given a trustworthy recommendation. Marketing survey data reflects this notion – salesmanship is the most important aspect of purchasing wine at a retail store. More research is need to further explore the needs and wants of millennial wine consumers.

RESOURCES

1.http://www.wineinstitute.org/resources/pressroom/07082016

2.http://www.wineinstitute.org/resources/statistics/article86

3.http://www.wineinstitute.org/resources/pressroom/07082016