Mount Etna is (literally) exploding. Sorry for the tired pun, but simply put Etna is one of the most active and popular volcanoes in the world. Etna’s popularity is due in part to its scenic and awesome eruptions shooting radiant lava, clouds of smoke, and bits of inner-Earth into the stratosphere. Etna is also very “hot” due to the delicious wines produced on the volcano. Okay, so I am not so sorry for the pun use!

Both Etna Rosso (red) and Etna Bianco (white) are spectacular and deserve high praise. Ask The New York Times’s Wine Critic Eric Asimov who has this to say about Etna Rosso: "No grape more than nerello mascalese illustrates the profound changes that have transformed the world of wine in the last 25 years." And with regards to Etna Bianco: "When grown in the right soils, under proper conditions, carricante makes one of Italy’s most compelling white wines, wholly different from any other. It’s a wine understood not so much for its fruitiness as for its savory elements, which is true of some of the world’s great whites."

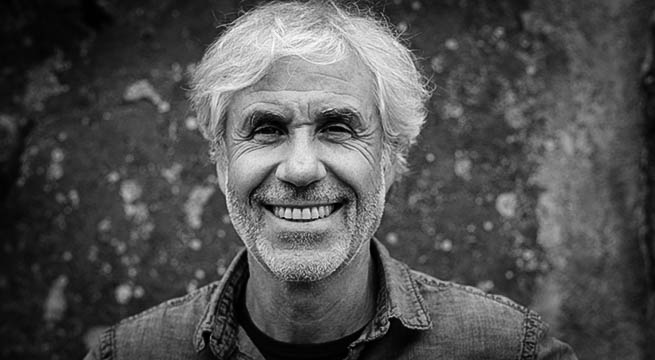

Few folks know Mount Etna like Salvo Foti. Born, raised, and currently living on Etna, in the town of Milo, Salvo lives to protect Etna, her traditions and people. A true Etneo! Throughout the years, Salvo has played an essential role in the recognition of Mount Etna wine, acting as a consultant for many wineries (Benanti, Vini Biondi, etc) that are now famous on the volcano.

Salvo Foti helped reestablish “I Vigneri” to protect and preserve the Mount Etna specific customs and traditions that take place in vineyards, in the cellars and throughout the winemaking process.

Salvo Foti helped reestablish “I Vigneri” to protect and preserve the Mount Etna specific customs and traditions that take place in vineyards, in the cellars and throughout the winemaking process.

Upon visiting Salvo, which I did back in 2018, he makes sure to set the tone quickly -- dismissing his wines being labeled as “Natural Wines” or “Heroic Wines,” rather offering the term “Human Wines.” Salvo is inspired to cultivate and nourish a culture of winemaking that is respectfully to human nature and tradition. After all, wine is not made without some human involvement.

In my interview with Salvo, he explains the human side of winemaking on Mount Etna.

Marco Salerno: Please tell us what Etna was like as a wine growing region when you were growing up.

Salvo Foti: Very, very different. Fifty years on Etna, especially in the higher areas, there was rural agriculture, made up of many small farms, vineyards, and orchards. Almost everything that was consumed was produced in the countryside by many farmers who took care of the whole territory. Bartering was widespread. The wine was almost all produced in the palmenti [stone buildings for fermenting wine] and sold in bulk to the many consumers who went up to Mount Etna at the weekend from the coast to buy wine and the many agricultural products produced on the volcano. Low-income viticulture, but genuine, sincere and truly respectful of the territory.

There are a few sides to Mt. Etna. Could you please tell us about the different areas on Mt. Etna? Why is Milo so special?

The Etnean territory, for its particular truncated-conical conformation, for its nature (it is a large mountain and an active volcano) for its altitude (over 3,000 meters), for its particular climate, unique in the world (it is a “North” in the South) and due to its geology (different lava flows), it expresses very different pedoclimatic environments, which have always influenced the local flora and fauna (and consequently also the people by Homo Ætneus). These important differences and biodiversity, in the case of viticulture, have determined the selection and cultivation of native vines specific to the Etna area, almost exclusively cultivated in this territory of origin and rarely exported, if not recently, to the rest of Sicily. The indigenous Etna vines, which we use to produce our wines, such as the white Carricante, the white Minnella, the red Minnella, the red Nerello Mascalese and the red Nerello Cappuccio, as well as being grown in their territories of selection and excellence, that is in their specific slopes and altitudes of the volcano, they are raised exclusively with the ancient system of the Etna sapling (Aegean sapling) by Etna winegrowers and with ancient and traditional production systems specific to this territory with planting density of 7,000-9,000 vines per hectare, on terraces made with dry lava stone walls, in order to contain the volcanic soil.

A clarification should be made regarding the particular Etna soils. Obviously these are volcanic sands, more or less fine, of different lava flows and ages. So the soils on Etna differ significantly between one area and another of the volcano. These are soils produced by the disintegration of lava flows with variable age and presence of minerals and not at all homogeneous.

Depending on the slope, it is also possible to find in the soil an abundant presence of ashes and lapilli that fall at each lava flow (so it can often happen during the year) rich in particular and unique mineral components. So these are terrains that we can define as virgin, primordial, visceral and in constant change. Let's remember that Etna is a perpetually active volcano, which never stops. The presence of these lapilli [unconsolidated volcanic fragment] on the eastern side of Etna, is significant, especially in the area of the municipality of Milo around 700-900 meters above sea level, where they play a particular role in the production of white wines from Carricante. This vine, more than others, benefits from the olivine, a particular mineral compounds contained in the volcanic soils, rich in silica, iron, magnesium and potassium, which greatly enhance the minerality of Etna Bianco Superiore, which can only be produced in the municipality of Milo.

The Milo area is also characterized by a particular climate, colder and more humid, ideal for the Carricante vine, which in this area was selected by the Etna winegrowers.

What is a Palmento and why is it special to winemaking on Mt. Etna?

What is a Palmento and why is it special to winemaking on Mt. Etna?

On Etna, the agricultural landscape was characterized by countless, beautiful and ancient manor houses, now mostly abandoned, owned by peasants, bourgeois and nobles. Each vineyard was equipped with a home for the owner's family and, invariably, for the palmento, that is the winemaking cellar, for the transformation of the grapes produced in its own vineyard. The palmento with its terraced vineyards, narrow streets, dry stone walls, all built in lava stone, was surprisingly harmonized with the Etnean environment.

Even today it is possible to see on Etna palmenti ranging from the essential to the sumptuous with very variable vinification capacities: from a few to thousands of hectoliters. In addition to the use of lava stone, a feature of the manufacture of Etna palmento is that it is built in such a way as to use the force of gravity in winemaking. The natural slope and rugged orography of the Etna area have been wisely exploited, becoming a resource for winemaking: the crushing area, the fermentation vats, the pressing area and the cellar are located at different and sloping altitudes. Between the end of the 1800s and the beginning of the 1900s, about 100 million liters of wine were produced in the Etna area: an enormous quantity of grapes transformed into wine using exclusively the palmenti.

The palmenti on Etna for the production of wines were used until the 1960s, obviously with some modernizations and technical changes. With the arrival of electricity, several manual operations were replaced using new equipment, but essentially the system continued to be the same as always. In 1997, with the strict and indiscriminate application of EU laws on food hygiene and safety at work, the palmenti of Etna were banned and definitively closed. This favored the industrial production of wine to the detriment of crafts and small peasant production.

The Etnean winemaker found himself, forcibly, passing from a wine producer to a grape producer. Having neither the financial means nor the time to adapt, Etnean winemakers gave up their most important income: that is, the sale of wine. The consequence was the drastic abandonment of thousands of palmenti and Etna vineyards and their irreversible destruction. Only very few producers, in disagreement with the laws, continue to use the palmento to make their wine, obviously considered illegal! The lack of exceptions, in the application of community laws, designed to allow, in a gradual and financially sustainable way, the adaptation of the Etna palmenti, has inevitably determined their degradation, the abandonment of large areas of the Etna territory and the loss of specialized winemaking workforce.

The adaptation of the Etna Palmenti to winemaking is now necessary and indispensable, if you do not want to completely lose the real estate and human assets that remain. New techniques, greater knowledge and a more conscious way of thinking allow us today to find solutions that integrate and harmonize the old with the new. The transition must be gradual, the changes not destructive but integrative and complementary.

THE ETNA PALMENTI ARE TO ETNEI WINES LIKE THE AMPHORES TO GEORGIAN WINES!

Recovering and using the ancient palmenti, in addition to maintaining, conserving and safeguarding the territory and all that it contains and represents, also means recovering, using and making productive the ancient winemaking techniques that we know today are fundamental in excellent wine production.

A TRUE AND ORIGINAL ETNEO WINE SHOULD BE PRODUCED IN AN ETNEO PALMENTO.

The laws must be reviewed taking into account real situations and adapting to the existing ones and looking to the future. They must be at the service of humanity, not against it or only for the benefit of a few.

At what moment did you decide to revamp the I Vigneri association? Please explain what I Vigneri as an association means and what it strives to achieve.

At what moment did you decide to revamp the I Vigneri association? Please explain what I Vigneri as an association means and what it strives to achieve.

The consortium of I Vigneri, which takes its name from my own company, was officially established in 2009, but since the early 2000s it begins to operate on Etna and subsequently in other suitable areas of Eastern Sicily (Noto, Vittoria, Aeolian Islands, Pantelleria).

The guiding philosophy behind the "I Vigneri" consortium is respect for man and the territory. The consortium that inspired me was founded for the first time in 1435 in Catania. It was re-founded by me with the same spirit and with the same purposes.

The consortium was set up between wineries that have in common respect for the environment, the cultivation of sapling vines, native vines, the same team of winegrowers, vine professionals, all from Etna. The common foundations are the territory and the winemaking philosophy that respects it. Our symbol, shown on the bottle that all the associated companies use, is that of I Vigneri, that is, a centennial alberello vine training method [head-trained bush vine], a symbol that dates back, like the original I Vigneri, to 1435.

The cultivation techniques we use, in the vineyards and also in the cellar, are those of the best and oldest Sicilian winemaking tradition, and Etna in particular. The alberello, a viticulture system with about 2000 years of history behind it, with a high planting density (8,000-10,000 vines per hectare), means that the winegrower must cultivate vine by vine, take care of plant by plant and therefore is not a mechanized, intensive and invasive cultivation, but respectful of the natural needs of the vine. Sapling cultivation, if carried out by experienced and sensitive winemakers, does not exploit the plant or the territory, so much so that the vines can live for hundreds of years.

A vine cultivated in this way will be so harmonized with its environment that it will give excellent grapes for the production of wine without having to be treated with chemical products and fertilizers and synthetic pesticides. The fruit ripens in the best possible conditions and in a natural way. In the cellar, when making wine, simply take care not to ruin the product obtained in the vineyard. You just need to apply some simple winemaking techniques and a lot of hygiene.

Please tell us a bit about the different areas where I Vigneri work.

Currently, the companies managed by consortium I Vigneri are located in areas of Sicily with the highest wine-growing vocation and in environments with particular landscape and cultural value: Aeolian Islands, Pantelleria, Etna, Noto. The owners of the various wineries are entrepreneurs, farmers, sommeliers, professionals, Sicilians, Italians and foreigners, who wanted to share the philosophy of I Vigneri: producing wine by enhancing and preserving the territory.

Can you comment on the Carricante project in California?

It is a project born about ten years ago at the explicit request of the owner of the Californian Rhys winery: Kevin Harvey. Kevin, the agronomist Javier (Chilean) and the oenologist Jeff, came to Etna after tasting an old vintage of Pietramarina di Benanti (I worked as an oenologist and agronomist with the Benanti company from birth, 1988, until 2011). They were interested in planting Carricante in California: they were the first ever to import this vine from Etna.

I gave them all the necessary advice for this vine as well as for Nerello Mascalese and especially the selected vines of the two varieties. Subsequently, in love with Etna, they invested by buying land and vineyards also in Milo for Carricante (Etna Bianco Superiore) and in Randazzo for Nerello Mascalese (Etna Rosso). Since 2014 I have been cultivating their vines and producing wines on behalf of Rhys, under the Aeris label.

What has been the most impactful moment in your winemaking career?

When my children, after their oenological studies done outside Sicily, decided to return and be an active part of the company: the commitment and objectives of I Vigneri have thus expanded over time, giving continuity and future to my work started nearly forty years ago.

What kind of future do you hope for Etna?

What kind of future do you hope for Etna?

The Etna I would like...

The Etna I would like is in my memory. And lively! Sometimes nostalgic and poignant. It crosses all the senses. The more intense the emotion, the more it remains indelible. It is the past tense that returns, often in moments of sadness. Sometimes a wine is an accomplice: its scent, its taste, so unique, excites me and immediately takes me back in time, to childhood among the Etnean millstones and cellars. I loved the October days. In that month the real refreshing autumn arrived, after the long summer, which sometimes continued even beyond the middle of September. With the new season, the first rains brought scents, colors, and new life. The air, full of energy, crisp, fresh I liked feeling it on my body.

As children, it doesn't take much to make us happy. As adults, we often don't fully appreciate what we have. We want more and now. We have to hurry up, grab as much as possible. Selfishness increases, it makes us worse. Patience begins to thin out, like vision. Bombed, pressed to have. We do more, but less well. We lack the time. We are struggling with it on a daily basis. Time is our great limit, anxiety is its consequence. We are less attentive to detail, form, completeness, and listening to others. It seems that we are no longer capable of even wanting to endure perfection, the pleasure of the small thing, of the moment.

Admire a bright beam of sunlight that kisses, illuminating them, the pink flowers of the soapwort, the silver-gray of the lichens on the black rock, the bright yellow of the broom flowers. All this happens in an instant and can remain imprinted on us forever. Can a moment be enough to make us happy?

Nature has the art of diversity. The capacity for perfection. It all makes sense for those who have the ability to grasp all this. Happy was Alexis de Tocqueville, who, struck by the vision, not of Etna, but only of its shadow, speaks of "a spectacle as it is to see it only once in a lifetime".

The time available, then immense for a child, often took me to walk willingly in the middle of the vineyards. I looked with pleasure at the vineyards, centuries old, which mingled with the wood, with the orchards, with the hazelnut groves and with them shared the black terraces and the vital soil. The vines were never regular. Different from each other, twisted around their chestnut pole, they appeared proud of their differences.

The chasing of the clouds in the sky, which in October play with the timid rays of the sun, highlighted even more a rainbow of colors, scents, emotions.

October on Etna was and is a special month. The month of mystery, of the miracle that has been repeated every year for millennia: the harvest. On Etna the harvest comes late, often when it is already over in the rest of Sicily. With the arrival of autumn, I already seemed to feel the acrid and pungent smell in the air that from then on a few days would be released everywhere, intense, during the fermentation of musts, from the millstones. A perfume that, like a mistral wind, filled the streets, intoxicated, excited us all.

In those days the roads leading to the vineyards were filled, at dawn and in the evening, with noisy people: the grape harvesters, who reached the vineyard in groups. We children watched the “chirume” [harvesters] paraded down the street. Intrigued by all those people unknown to us, festive, joyful. During the harvest, the day started early also for us "carusi" [boys], who wanted to help, participate in that party. We filled our small baskets with grapes until, in a short time, we were not tired. There was a strong curiosity to go around, never wanting to sit still: now in the vineyard to eat a bunch of grapes and then run to the palmento.

The palmento fascinated me. I stayed for a long time, maybe hours, watching my grandfather and his helpers go up the stairs and, through the window overlooking the outside, unload the grapes into the "pista": a large and low lava stone basin, and “pistaturi" who, barefoot or after wearing heavy boots, crushed those large black and turgid clusters.

The palmento fascinated me. I stayed for a long time, maybe hours, watching my grandfather and his helpers go up the stairs and, through the window overlooking the outside, unload the grapes into the "pista": a large and low lava stone basin, and “pistaturi" who, barefoot or after wearing heavy boots, crushed those large black and turgid clusters.

I remember the sound of their small rhythmic steps, their hands behind their backs, they seemed to me to be dancers. Their songs that helped them keep the rhythm are still present in the memory. From time to time, the group stopped just as my grandfather screamed: and poles! I yelled every time he found me unprepared, making me jump with fright. Immediately everyone took the shovel and pushed the pressed grapes into the central part of the "pista", reforming a new bunch of bunches. At that point the thing that amused me most happened: the pressing with the “sceccu,” the donkey.

To further press the grapes, a kind of wheel built with intertwined willow branches was placed on it, precisely the "sceccu," on which the "pistaturi" climbed at the same time. With their arms placed each on the shoulders of the other, they began to climb onto the "sceccu" by placing only one foot on it, while the other remained firmly on the ground. At a certain point all together jumped over at the same time and flexing and extending the knees, further pressed what remained of the bunches. The red must drained in batches, first more abundant then more and more sparse.

Then came the pressing of the pomace with the press called "conzu." The “conzu” was a difficult machine, where I noticed, more than at other times, my grandfather's apprehension. I watched the large oak beam move in a state of fear and curiosity, petrified in front of that infernal device, until I heard my grandfather scream at me: worried I might hurt, he sent me away. Frightened I ran out. Not much time passed and I returned to the palmento, looking, in the general excitement, for the face of my grandfather: his smile and the dripping sweat on his forehead made me understand that he wanted me to bring him "u bummulu," the terracotta jug with water.

Frantic, intense days. The harvest was a mix of colors, people, songs, sounds. And in the chaos of the millstones, as if by magic every year the mystery was repeated: the fruit of the vine, the grape, from sweet, juicy, just pressed, began to bubble and emanate an intense aroma and heat, until it was transformed into something completely different. For me as a child, the mystery was even more inconceivable, because it was allowed to eat grapes, but it was forbidden to drink the result of that mysterious transformation: wine.

Curiosity and pleasure made me fearless and in the general confusion of those days I repeatedly drank a little of that bubbling, tepid and sparkling liquid that quickly changed his way of being. The taste, initially sweet and fresh, then became acid, sour, savory. The stomach ache that I regularly got and that I tried to keep hidden from my grandparents, was never a sufficient deterrent to stop my constant tastings, to give up that subtle pleasure.

October, every year, also brought with it a strange pathos made of anxiety, trepidation, excitement. It was the prelude to the harvest that put us all in a state of worry mixed with joy. We were aware that it didn't take much for a year of work to go bad. The gray clouds, full of humidity, passed over our upturned noses: the scent of rain was intense in the air. The eyes seemed indifferent, but there was the concern to see the clouds attracted by Muntagna [the mountain, Etna] stop. The rain so desired at other times was now frightening. We pretended nothing happened ... in Muntagna you say ca nu gniovi ... na paura... [the mountain says it doesn't rain ... don't be afraid] my grandfather said.

October, every year, also brought with it a strange pathos made of anxiety, trepidation, excitement. It was the prelude to the harvest that put us all in a state of worry mixed with joy. We were aware that it didn't take much for a year of work to go bad. The gray clouds, full of humidity, passed over our upturned noses: the scent of rain was intense in the air. The eyes seemed indifferent, but there was the concern to see the clouds attracted by Muntagna [the mountain, Etna] stop. The rain so desired at other times was now frightening. We pretended nothing happened ... in Muntagna you say ca nu gniovi ... na paura... [the mountain says it doesn't rain ... don't be afraid] my grandfather said.

In the evening, all around the basin (the warmer), we listened to u Nannu [grandfather]. His stories, deliberately scary for us children, fascinated us. On one of those evenings, around the hearth, waiting for the harvest, with an expression of someone who is confiding a secret, a great truth, u Nannu [grandfather] ruled: Carusi, riurdativillo sempri u vinu becomes ca racina, sulu ca racina! [Boys, always keep in mind it’s the grapes that make a wine, only the grapes!]

I was amazed by this banality. Of course no, wine is made with grapes, only with grapes!

Many harvests have passed since then and this banal truth often comes back to my mind. In the era of the most sophisticated techniques, of global knowledge, of capable biotechnologies, it seems, of everything, my great-grandfather's words come back to mind: ... riurdativillo sempri u vinu si fa ca racina! [Always keep in mind it’s the grapes that make a wine, only the grapes!]

Yes, wine must be made with grapes, with love, honesty, respect for the environment and for man: these are the best ingredients of a wine, the real one, which has always been etched in my memory.

And this is the Etna I had and this is the Etna I would like for my children.

Editors note: A special thank you to the Vinitaly International Academy, as the embedded video and the top photo portrait were taken during an October 2021 Vinitaly International Academy trip to Mount Etna.