We were at a tasting where several producers from around the world were presenting their wines and, as usual, we had split up to sample as many as possible. Suddenly, Dottie looked up from a glass of corky Champagne and John was standing there, his eyes big as the base of a wineglass and his mouth wide open.

“I just took a sip of a wine and I feel like I stepped into darkest space,” he said.

Sure, we had recently seen the New York Philharmonic play the score of “2001: A Space Odyssey” while the movie showed on a giant screen, but, still, this was very unusual behavior.

THIRTY SEVEN YEARS EARLIER

When we first lived in New York, we used to go a place called the Blue Grotto, before Little Italy became quite the tourist draw it is now. We walked down several steep steps and into a different world. It was loud and crowded, with an open kitchen and charmingly gruff waiters who always seemed about to bump into us with giant trays of food. Dottie had sausage contadina, John had lasagna and the spiedini we shared is still the best we ever had.

When we ordered wine, we got a bottle of red – as far as we know, that was the only wine the place had. It was called Segesta, it was made by Diego Rallo & Figli, it cost $11.50 and it said in big letters on the top of the label “Vino Delizioso di Sicilia.” It was kind of rough-hewn, but, in that environment, it was delicious.

That’s pretty much what we thought of Sicilian wine then, and for a long time afterward. Alberto Tasca d’Almerita (photo right by Grape Collective), 46, knows a lot about that era. Now the CEO of Tasca d’Almerita, one of Sicily’s oldest and most respected wineries -- he’s the eighth generation -- he first got involved in the business in 1991, when the island’s Marsala business was in decline.

That’s pretty much what we thought of Sicilian wine then, and for a long time afterward. Alberto Tasca d’Almerita (photo right by Grape Collective), 46, knows a lot about that era. Now the CEO of Tasca d’Almerita, one of Sicily’s oldest and most respected wineries -- he’s the eighth generation -- he first got involved in the business in 1991, when the island’s Marsala business was in decline.

Sicily, a Mediterranean island often described as being ‘“just off the ‘toe’ of Italy’s ‘boot,’” produced boatloads of table wine back then, literally boatloads: “We were just bottling 15 percent of total production, so 85 percent was bulk wine and sold somewhere else,” usually anonymously, to add heft to wines all over Europe, Alberto told us recently.

In 1993, he told us, a seminal market research study found that the worldwide perception of Sicilian wine was “heavy wine, high alcohol, bulk wine. Everything was really a low-grade reputation.”

But a new generation was emerging. They had traveled internationally and knew their wines didn’t stack up. They knew they needed to do something. A few families, including his own, the Rallos, the Planetas and others, helped lead the charge, but it wasn’t easy. “I remember the first meeting, the first event we organized together,” Alberto said. “The difference with other producers – it was like we were living in different countries. No common view. That was crazy.”

The forward-thinkers had a plan: Since the world was crazy about four varieties – Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc – they would produce more of those as varietal wines and prove what Sicily could do. Of course, Sicily had many of its own indigenous grapes, like Perricone, but start with something people knew. How hard was this to do? So hard that Alberto’s father, Conte Lucio, first had to plant these varieties surreptitiously in 1979 because his own father, Conte Giuseppe, would never hear of it.

It worked. “They totally shocked the world,” Alberto said. “And that was the key to explaining that Sicily has the potential for power combined with elegance and longevity. After that, everything else was a little bit easier.”

THIRTY FIVE YEARS AGO

(Photo - the Etna vineyards of Donnafugata)

Gabriella Rallo inherited new vineyards and she and her husband, Giacomo, a fourth-generation winemaker, believed they could produce high-quality wines that would break with the image of the past. If the name Rallo sounds familiar, yep, that’s the same family that made our wine at the Blue Grotto and which had been making wine in Sicily since 1851. But they wanted a fresh start and they created a whole new brand called Donnafugata Winery in 1983. They sold Rallo a few years later.

“Our parents were always looking forward toward something new and innovative,” the fifth generation, José, 54,

and her brother, Antonio, 51, told us by email. “In their vision the territory of Sicily [could produce] wines that could be complex but also elegant by introducing new techniques in both the vineyard and cellar.”

ONE MONTH AGO

At the tasting, John was happily enjoying a taste of a stunning Bruno Giacosa Barolo when he heard a winery representative at another table say, “…and this is a blend of Nero d’Avola and Petit Verdot.”

He was sure he had misunderstood. Nero d’Avola, Sicily’s signature indigenous red, is a bold wine, peppery and deep, with good tannins. Petit Verdot is that and more. It can be such a monster that a top Chilean winemaker who puts about 5 percent Petit Verdot into his Cabernet told us recently that even one percent too much can ruin the wine.

John sidled over and asked if he’d heard correctly. The representative said he had and offered him a sip – the sip that left him feeling he was in deep space. It was amazing – deep and rich, with blackberry-blueberry fruit, minerals, earth and tremendous presence, yet surprising elegance at the same time and a notably dry, drink-another-sip-immediately finish. That’s when John rushed over to get Dottie. The representative poured some for her and showed us the bottle. It was Donnafugata Mille e una Notte, and Dottie, being more comfortable with languages than John, translated, “A Thousand and One Nights!”

(Photo - Donnafugata's Antonio Rallo)

As the Rallos were proving what Sicilian wine could be, they hired the famous winemaker Giacomo Tachis, who created some of Italy’s iconic wines, to advise them. He helped create Mille e una Notte. The first vintage was 1995. Its exact composition is a secret, but its biggest component is Nero, followed by Petit Verdot, then some Syrah and other grapes.

We got a bottle of both the 2013 and 2014 to drink on our own to find out if it was just Stanley Kubrick talking (they cost about $80 each). It wasn’t. They are stunning wines, with super-ripe fruit and yet such great acidity that they seem almost lean at the same time. “Amazing focus for such a big wine,” we wrote about the 2013. The exceptionally dry finish never stopped surprising us. These are proof that a wine can be big and souful and yet also elegant and thoughtful. They are, simply, world-class.

Donnafugata, which has five estates scattered across Sicily, produces 2.4 million bottles of wine, winery representatives said. It made only 25,000 bottles of Mille e Una Notte in 2014 and 40,000 in 2015. “We only select the best grapes of the varieties for the blend of Mille e Una Notte. This is why volumes may change from vintage to vintage,” the Rallos told us. “We focus on low production and carefully monitor each single plot’s individual maturation in order to be able to choose the right picking time to assure the best balance between phenolic and sugar ripeness and to retain good acidity.”

TODAY

The Sicilian wine industry is in the midst of one of the more exciting rebirths in the world. The discovery that Mount Etna, on Sicily’s eastern edge, is a great winegrowing region had a lot to do with it, but so did the generation that had a vision for the future. Sicilia DOC, a sign of quality, was established in 2011 and the Producers Consortium for the Sicilia DOC, a large trade group, was established the next year. The consortium’s first president was Antonio Rallo, who also has led Assovini Sicilia, the preeminent organization of winemakers of Sicily, founded in 1998 by his father and two other pioneers, Diego Planeta and Lucio Tasca d’Almerita, whose offspring have also served the organizations.

With Sicily’s increasing confidence has also come a rebirth of its indigenous grapes. Nero d’Avola is now widely available, as is Sicily’s most-planted fine white, Grillo.

“We never abandoned the indigenous grape varieties,” said Alberto Tasca. Tasca d’Almerita, a name we have trusted for years, now owns five estates with a total production of about 4.1 million bottles and Alberto Tasca is a leader in Italy’s movement toward organic, sustainable winemaking.

To see what’s happening, aside from the Mille e una Notte, check out Tasca’s Lamùri, which is 100 percent Nero d’Avola and is under $20, and its Rosso del Conte, which is 70 percent Nero d’Avola and 30 percent Perricone. The Lamùri is dark, flavorful and delicious with savory dishes – light enough on its feet to be easy to drink and happy to be a supporting player. The Rosso del Conte? Well, what a unique wine, in a very good way. We got oregano, basil and rosemary on the nose. The taste was herbal and spicy; Dottie likened it to herbs steeped in black tea. There’s a hint of walnuts – a slight bitterness – along with rich fruit. It’s a challenging, serious wine meant for a serious meal with your most wine-loving friends. It costs about $60.

THE FUTURE

When we asked Alberto Tasca if the world has caught up to the renaissance of Sicily’s wine, he said, “I think we are at the beginning.” He said one signal will be when consumers realize Nero d’Avola isn’t just Nero d’Avola, but a very different wine depending on where it’s grown.

(Photo - Lucio and Alberto Tasca d'Almerita walking the vineyards)

Christine Hammond, Tasca’s brand manager for the U.S. and Canada, who has been involved in Sicilian wine for almost 20 years, said that, roughly speaking, she’d say the Nero planted in the west is more fruit-forward and jammy; in the mountains, higher in acidity; and in the southeast, darker, with “broodier” flavors.

Antonio and José Rallo have a similar dream, that consumers not only warm to Sicily’s wines in general and its indigenous grapes in particular, but understand what a rich winemaking area Sicily is.

“One of the biggest challenges is to explain the immense potential of Sicily as a wine-producing country and the great variety of grapes and wines produced from different areas with completely different terroirs,” they wrote us. “People commonly think of Sicily as a small island and are not aware of its actual size and the fact that Sicily is the biggest vineyard in Italy, three times as big [in vineyard acreage] as New Zealand and equal to Germany and South Africa, offering an extraordinary diversity.”

It clearly doesn’t take HAL 9000 to see that Sicilian wines are really about to break through.

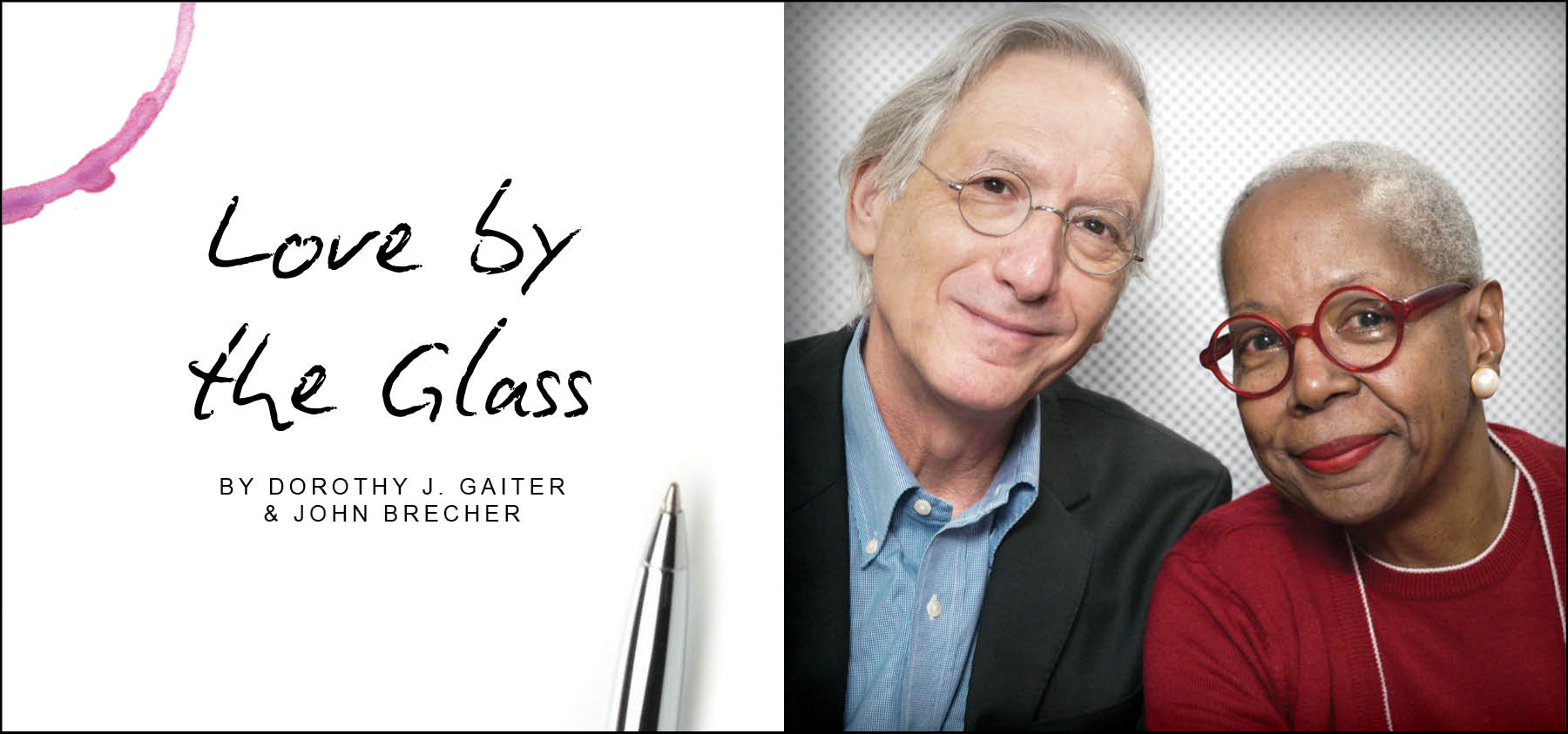

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

For more on Donnafugata check out Jameson Fink's interview for Grape Collective.

Banner art by Piers Parlett, photo illustration by Zoë Brecher