Giuseppe Sesti has had a colorful life. Prior to wine, the Venetian born Sesti ran a Baroque opera festival and wrote books on astronomy. Sesti discovered Montalcino while visiting the region with his English wife Sarah, fell in love with the land and in 1975 purchased a ruined castle - Castello di Argiano, a 13th century property with Etruscan origins. During his early years in Montalcino he learned the wine business by serving as a translator for the local winemakers when they had business meetings - as he was one of the few to speak English well in the area. Through his interaction with the winemakers he developed an interest in Brunello. He was inspired to plant his vineyards in 1991 and today practices biodynamic principals in his winemaking. The estate consists of 254 acres of which nine are planted to vineyards.

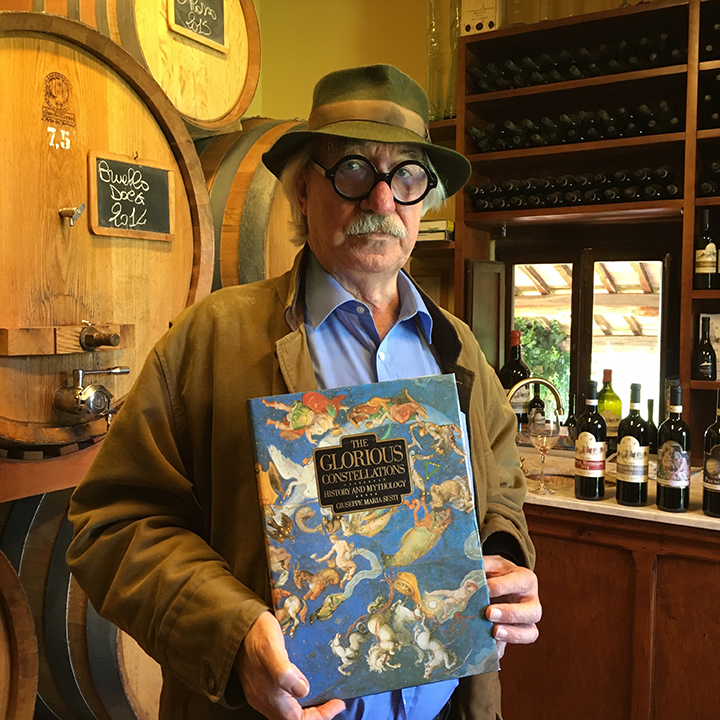

His study of astronomy and lunar cycles has influenced his winemaking and his agricultural practices. Sesti is the author of The Glorious Constellations: History and Mythology which traces the evolution of the constellations through various ancient cultures which is available on Amazon.

One of the early Brunello pioneers Sesti talks to Monty Waldin about the Brunello scandal, organic farming and why paying attention to lunar cycles makes sense.

Monty Waldin: Giuseppe, explain what your philosophy is when it comes to making wine at the Sesti winery.

Giuseppe Sesti: Well, it's interesting that you call it philosophy, because I love philosophy, but my approach is the most natural possible approach. I'm sitting on the best possible land for a vineyard, surrounded by woodland, which is a land of oxygen. The terroir, the driven flavors of terroir, they're all there. One of the reasons I'm using barrel, an old-fashioned way of winemaking, is because there is nothing to tame. If I have soft tannins, beautiful fruit, and terroir-driven flavors, why should I cover it up with oak?

Secondly, because of my experience in astronomy and the history of astronomy, I use the moon for the "travasi," the racking.

Moving wine from one barrel to another.

Yes, for racking and for planting or pruning in the vineyard, because the moon has been used for thousands of years, and until the invention of chemical laboratories, the moon was the winemaker's method.

You studied astronomy, didn't you, when you were younger? Where did you end up doing that? It wasn't in Montalcino, was it?

No, it was in Venice. In Venice, when I was younger I had many young people question themselves and say things like,"What is time? Why we were there before? Why we are here now?" We have no idea what's going to happen next. I had the Marciana Library in St. Mark's Square in Venice, which is the best and the first mobile library in Italy. The librarian was a friend, a family friend, so I had free access to it, so I'm self-taught. In fact, they call me technically an independent researcher.

To go back to the moon and the wine, that allowed me to reduce a lot of the sulfites in the wine. The reason is that liquids, women, fish, and all sorts of creatures on the planet use the moon as a biological clock. If you touch the wine at certain moments, the wine is stronger and less subject to crisis. How you cure the crisis is with sulfites, so the better you handle the wine with the moon, the fewer sulfites you need to stabilize the wine.

What is a good time? Just say you're bottling the wine, which is a very important thing. Obviously it's where the winemaking journey ends. What is a good moon to bottle the wine under?

Well, it started earlier. The minute you assemble the wine, that's an important moment with the moon.

Assembling, you mean by blending all your barrels together to make one lot that's...

One lot which is then a Brunello of the year, and so that is done with a good moon, and then it's transferred in a big, stainless steel container to make one wine. Then you have to ask for permission. You can't just bottle, under Italian law, so you have to present the wine, pass the test and all that, and then you bottle. Then you choose the next moon.

When you say the next moon, are you saying full moon, or are you talking about the ascending and descending moon?

After the full moon. For the red wine, the waning moon.

When the moon has gone through its full moon, its biggest size as we see it, it's getting smaller and smaller.

After that, because when the moon is growing stronger, the wine is a little bit agitated, and after the full moon, it has a relaxation time of about 10 days, I would say, and that's ideal.

Does your mood change according to the moon? If we turn up for an interview on a day when it's a bad moon, are you going to be very grumpy and not answer the questions? Do you feel personally, physically affected by it?

Well, yes. There are a lot of people coming and going in here, and then when there's a full moon, they have more agitated nights. The police in New York increase the number of policemen during the nights with a full moon. It's famous, but not just in New York. All over the world, the moon has a power, and a part of that power is to stabilize the earth. If the moon was not there, we would not have the planet as we know it, because it would spin like crazy, so the moon is important.

In terms of your family, how did you actually end up here? People tend to think that Montalcino, it's all pristine and it was all made, but it was pioneers like you that helped create it. What's your personal story?

My personal story is that we came to Tuscany first with my wife and two children, and we first stayed nearby in Monte Amiata, where Elisa was born.

Your daughter.

Yes. Then we were staying at a farm which belonged to a friend who went to work in Africa for two years. We fell in love with the area, and we were looking for a place to stay and to settle. We found this place, which was kind of an archaeological site. Everything was collapsing, abandoned. The estate that it belongs to was bankrupt after the war, and so we started to do a bit of restoration and clean up. It was all completely overgrown. My mother and my father came from Venice and when my mother saw the place she said, "Are you going to live here with your children?" I said, "Yes," and she burst into tears.

Castello de Argiano

Because it's just totally ruined, and overgrown, and chaotic.

Well, she described it as a viper's nest.

Literally, because there would have been snakes here, wouldn't there?

Oh, plenty. One of the first things we did when we settled was to have bantams and turkeys, because they are the best cleaners of snakes you can possibly have. Anyway, at the same time, I was doing my writing, and I joined the festival of Batignano, which is Baroque opera. I'd been working there from '74 till 2004, 30 years. That was fun, but a lot of work. At that point, the decision was, do we restore the castle and finish all our money, or do we do restore the land as well? That's when we planted the vineyards, so it is part of a project of restoration of a place that for thousands of years has been related to the land.

What is this Argiano? That has a significance, because your winery is right opposite this big volcano called Mount Amiata, which is very influential in terms of the climate. It makes this area particularly warm because it blocks the cold air. What is Argiano? Where does that name came from? You're the Castello de Argiano, the Castle of Argiano.

Argiano comes from the Latin "Ara Jani," which means the "altar of Janus," the double-headed god that gave the name to the month of January. The altar of Janus used to be a very important shrine for pilgrims in Etruscan times [between the 8th-century BC and the 3rd-century AD]. Then when the Christians came, they looked rather worried about too many people going to the altar of Janus, so they decided in the 8th century to build a church on top of it to get rid of the competition.

Basically the Christians were worried about Pagan rituals. They wanted to stamp that out, so we're going to literally cover this altar, this worshiping place, if you like, with stones, and build this tower.

Yeah. Well, they built a church, really. It took another three or four centuries before they built the tower for defensive and attack reasons. One of the resources here is that there is a landscape and woodlands around. This landscape is exactly the same as it was 400 years ago, 500 years ago or more.

It hasn't changed, you're saying.

It hasn't changed at all.

This is a place where you could actually survive as a human, eat quite well, and then you come along and added the wine to that.

Yes. We have porcupine, wild boar, deer. In fact, we had to fence some of the vineyard. Otherwise, there will not be a crop to harvest.

They [the deer] would eat all the grapes?

Yes.

Giuseppe, you've been here for 45 years in Montalcino. What has changed over that period, and have the changes always been for the best?

Well, it was very quiet. Montalcino was not known by that many people, internationally speaking, but what happened is the gift of Biondi Santi to the city of Montalcino, and with a very, very strict disciplinare [meaning the rules under which grapes for Brunello must be grown and rules on how the wine must be made, aged in wood, and when it can be bottled].

Rule book.

Rule book. It has created a structure in which gradually some of the farmers turned into producers. They started to work very well, and gradually the name became more interesting. In the '70s, it was the end of the '70s, there were investments from America, from other parts of Italy, and so the '80s really was when the Montalcino and Brunello became internationally known. That's what happens. It just happened. My involvement with that was not as a vigneron, because everybody asked me to help them when they had visitors because nobody could speak English. Not that my English is that good, but I went there not as a job but as a good Samaritan helping everybody.

I introduced many, many sellers, big and small, to the international press, buyers, university professors, and so on. In doing that, I tasted all the different Brunellos, had wonderful meals, and I made up my mind which were the wines that I really, really liked. I discovered that it wasn't necessarily a great investment in technology and digital solutions that were producing better wine. I'd done that for something like seven or eight years, and at the end, I knew everything about the process, the grafting, my way around, and I decided to plant my vineyard.

Guiseppe Sesti photographed by Monty Waldin

Basically, by acting as a translator or a helper, if you like, to these professional wine buyers, you learned what the local wine growers were doing. You picked up all the tips. When did you start planting your own vineyards?

In '89.

You always said you wanted to work ... we call it naturally now ... but you always wanted to work with nature rather than against nature. How did people view you at that time? Did they think, "This crazy guy, he's talking about the moon. He's a bit of a philosopher. He's never going to succeed?" Or where they encouraging towards you?

The answer to that is that there always [were here] old farmers who started planting vineyards and [who were] making my favorite wines. They were rather natural and rather old-fashioned, but then the wine dramatically changed when technological investments came in. This is important because the sons of these farmers, they went all for the digital [meaning opted for much more modern techniques].

Right, so basically you're saying within a generation, Dad was farming a few grapes, maybe had some animals too, making traditional wine, which appealed to you, but then their sons came in and money started coming in. They just said, "All right, we're going to invest in lots of technology."

Exactly.

Then what was the ultimate consequence of that?

The ultimate consequence is that they never changed the disciplinare...

The rules, yes.

The rules, and what used to be three years in oak and two years as you like it became two years in oak and three years as you like it. This attracted the new generation to French winemaking with a barrique, because that's what you need, two years in a barrique. I never followed that fashion, and we still use large barrels because we have this gift from the soil position. The microclimate here is fantastic.

Obviously I can see what you're saying, these smaller barrels give a much more directly oaky taste to the wine much more quickly, which is maybe what the international market wanted. But in terms of the actual idea that Montalcino or Brunello was supposed to be 100% Sangioevese wine, there are some issues there as well, with the kind of French-ification, if you like, of the ... ?

Yes. Well, a few of us, we were calling it the carpenter's wife because lots of people have no idea how to age wine in a barrique.

To wine that just tastes of wood, basically.

The darkness was too much. It [Brunello] was kind of an ink [meaning atypically dark in colour for a wine supposedly from only 100% Sangiovese grapes, Sangiovese not being the darkest coloured grape compared to say Merlot or Cabernet]. In fact, after all the vicissitude, recent problems, et cetera, now there are a lot of people have gone back to the traditional method.

You must be happy about that, though. You've seen the full circle: the traditional, then this fad for French-style wines in Italy, which is just kind of wrong in your view, and now we're going back the right way. Are you optimistic, then, about the future?

Very good. It's the best thing that recently happened to the Brunello and the 2010 ...

The scandal, yes.

The 2010 Brunello shows how successful it can be.

So without wines that don't taste of French grape varieties which are not allowed, and they don't taste too oaky.

The scandal of the Brunello was the best thing that we ever had in Montalcino because it had seriously damaged the image, and everybody got an enormous fright. Everybody stopped blending under the table, and so we went back to the Sangiovese, which is the best news ever. Now the quality you can see throughout the wine now. There is no more of that kind of heavy, dark color which is rather unnatural. It's not Sangiovese. So it's beautiful.

Basically, the idea with Brunello, it's a wine made from one grape, Sangiovese, which doesn't really have a particularly deep color and has a very particular kind of smell, and it seemed like these wines were being made that were much darker in color and smelled more of French grapes. What was actually going on? What was alleged to have gone on?

What Sangiovese needs is the right position of vineyard in the right soil, the right microclimate, and it was very successful because basically the vineyards were planted that way. But then the success of the Brunello attracted a lot of investors, insurance companies, lawyers from Rome. Foreigners came in, and they all started to plant vineyards in places where the Sangiovese is not happy.

Then they put an oenologist there, absentee landlord, and this poor oenologist had to get these wages paid. Then of course, when the vineyards are in the wrong place, he'll get wine which is not that interesting, and that's what triggered the blending. They needed to boost it up, this wine, and then, because so many were doing that, it sort of became a habit, until everything was discovered and the scandal exploded. Then it not only exploded, it was very badly handled by everybody.

Monty Waldin, Elisa Sesti, Guiseppe Sesti

When you say badly handled, one of the allegations was there were really a lot of producers who were adding non-Sangiovese grapes to their Brunello, but in the end, not many people were told off, were they? There were very few wineries that were convicted of anything. You say it was all hushed under the table.

Yeah, but a lot of wine also had to disappear because it was already blended in a barrel.

You're saying that there were wines in barrels that were not just 100% Brunello. They'd been blended with, say, Merlot or Cabernet. What happened to those wines? They didn't just pour them down the drain.

Those wines, they had to disappear. They'd been sold maybe in bulk or something, but if they were analyzed and everything, they would actually be illegal, not conform to the disciplinary rules. That's why the scandal was positive, because it pruned all these habits, bad habits, off the Brunello. Now you get this Brunello which is good for everybody. It's not just, "Oh, my wine is better than yours," and that kind of mentality. It's a fact that here, a good vineyard produces good wines and good Sangiovese, and when Sangiovese is good, it's unbeatable, so it's very, very important.

I think a lot of people would agree with you, that Montalcino is in a much stronger place than it was before the scandal. The wines are more typical. They really do taste of Sangiovese. They really do taste of Montalcino. It's a tremendously exciting time. What is the next step, do you think, for Brunello? Is it thinking about how to get more tourists into the region? What would you suggest, with all your experience?

If everybody plays an honest game, Montalcino will be all right. It's just what can go wrong in Montalcino is what happens behind closed doors, and corridors, and political arrangements, and all those kinds of games. Montalcinese, all the estates which have a heart, and a passion, and a will to do it well, they will be okay, and the results are beginning to show. It's not a plan. It's just sometimes you need a scandal to create the background of this purity or honesty to attack the winemaking. All you need is good wine. Everything will be fine.

You were planting some extra vineyards now, weren't you? Because the demand for your wines is so strong.

That's my daughter. We are small. We had nine acres, and then now my daughter decided to put it up to 11 1/2, something like that, and good for her. She's young, but again, it's the quality which counts. The quantity is only suitable for supermarkets.

Do people still think you're a little bit funny when you talk about working with the moon? Do people think, "He's a bit of an oddball, old Sesti. He's a bit living in the past?" Or do they actually think, "Well, actually maybe as natural wine comes back into fashion, he's actually right," that these natural cycles are well worth paying attention to?

Well, there are a lot of people that think I'm a lunatic, but what is interesting now is that some oenologists, they have opened their ears to these things. When the proof is in the pudding, as you say in English, if you have a good wine which tastes natural and has terroir-driven flavors, you're a winner.

So even despite their scientific training, these oenologists or wine scientists, even though they may not think about believing in them, it's actually, as you say, the proof is in the pudding. They're saying, "Well, maybe this Sesti guy isn't a complete lunatic after all."

Well, sort of. I'm not the only one who tries to do this. There are other producers, which is interesting. It is wonderful for the future. These guys have continued to work as they work, and the big guys should readjust things, because technology is a wonderful thing. It saves you a lot of backache, and also, if you use it properly, it is an advantage. I'm not saying that we are going to go back to the Roman winemaking or the Greek winemaking because it's impossible, but there is a marriage between technology and a naturalistic approach for the Sangiovese.

Yes, and your wines are a very good example of that. Some people could maybe divide the Brunello di Montalcino wines into traditional and modern. What is that dividing line?

Well, it appears, especially in the '90s, that people were doing shorter time in barriques, sort of, but the proportion between oak and wine was reduced to each one of them 20 liters. Then you can keep it in stainless steel until it's bottled, or you can bottle it immediately if you have a space to keep it. It's a little bit of saving time and work and all that, because with the way we do it, almost four years in barrel, one year in a bottle and then we commercialize it as a Brunello, you need to look after the wine. Also, you have to have more oak in the sense of barrels because you always have four vintages in a cellar, one in a bottle, so you need space, you need organization.

The modernist approach, they use that way. As for the traditionalists, more and more people are abandoning the [225-litre] barrique, and they're buying the barrels, the larger barrels [500-litre tonneaux for example]. I'm not saying that is the whole solution, because if you put wine in a barrel, it doesn't change. You have to fill the barrel with good stuff, proper stuff, proper Sangiovese, and that is what is part of the process, and then looking after it, and then, and then, and then. Be simple.

You're saying there's now more of a focus on getting better quality grapes and not oaking them so much, not blasting them with French oak so that all the wine's going to taste the same. You feel that the pendulum is swinging back more towards traditionalism.

Well, they have to, in a certain way, because Sangiovese, by nature, all you need is a touch of oak, a little bit, nothing much, because the wine has to speak for itself. Pinot Noir and Sangiovese are single-variety grapes, and they have to be handled with great simplicity. Of course, there are a thousand miles from one vineyard to the other, so the methods are slightly different, but the mentality has to be that one.

They're both, like Sangiovese for the Brunello, very easily over-oaked. It's a very sensitive grape variety.

Yes. It is a difficult grape also to look after in a vineyard because it's an early starter, subject to late frosts, and it needs ideal conditions. They tried to plant it all over the place, including Australia, with disastrous results. Also, there are 35 varieties in the family of Sangiovese, and only four or five are the ideal ones, especially the ones which have been adapted to the microclimate, so the grafting is important. There are all sorts of little tricks to keep the core going.

Tell me about the core. The core of Montalcino, the actual people here, how has that changed over the time you've been here? You say initially there were really just local people making a bit of wine for themselves, and now it's changed. How has it changed, and has it been for the better?

Well, Montalcino lost a lot of its population. The residents all kind of bought modern houses and are satellite positioned, but in the actual center, the historic center, everything is for sale, because it's Montalcino, and so that creates a bit of a lack of a village life in that sense. Of course, many people have either become richer because of the Brunello, and some sold their vineyards for good prices and they've gone to live somewhere luxurious. Once upon a time, the market was in the middle of the village, and they had to move it a bit above because it was too inconvenient.

There are other little changes. I suppose they happen in every village, but in Montalcino, I'm sad to say that when the scandal was there, I was expecting people to go in the street to say, "No," and be proud of what they were doing and all of that, and nothing happened like that. It was kind of very strange for me, because they were not very warm or patriotic about their own produce.

Maybe they were scared of voicing an opinion in public about what could have been or what turned out to be a seminal moment in Montalcino's history.

Yes, but anyway, that fortunately is over. What is not over is that a lot of Montalcinese are leaving, or selling, but I suppose it is a natural phase.

Yeah, it's people cashing in, isn't it? If there's a boom in Brunello and you have a nice house in the center, why wouldn't you sell it for several hundred thousand euros?

Yes, but some families, some people, are getting too old. Children are not interested, and what do you do? When you start to reach 80 and you don't have a generational turnover, then you sell. It's sad, but it's like this, and it's also natural that it's like that.

Just explain a little bit about your relationship with Kermit Lynch, the American wine importer.

Talk about generational change. My daughter is now in charge of the business, and the winemaking, and everything. She was not particularly keen on my choice of an American importer, so she met Kermit Lynch, and they started to have this relationship. Kermit said to her, "We like the wine, but if we do it we would like to have exclusivity," and she said, "Well, let's not rush too much." She said, "What about a year trial in California, and see if we like each other?" Indeed, that happened. For a year, the wine did very well. The relationship went fantastic, and Kermit Lynch specializes in smaller producers. He likes a proper relationship with his wine producers, and so it was perfect. Now we're just going ahead happily, very, very well.

---

Monty Waldin was the first wine writer to specialize in green issues. He is the author of multiple books, including The Organic Wine Guide (Thorsons, 1999); Biodynamic Wines (Mitchell Beazley, 2004); Wines of South America (Mitchell Beazley, 2003), winner of America’s prestigious James Beard Book Award; Discovering Wine Country: Bordeaux (2005) and Discovering Wine Country: Tuscany (2006), both Mitchell Beazley; and Château Monty (Portico, 2008).

Buy Monty Waldin's guide to the best Biodynamic wines on Amazon.

---

You can find Sesti's Brunello at the Grape Collective.