We were at a walk-around-wine tasting of the portfolio of the wine importer Vintus recently when a woman with a twinkle in her eye asked Dottie if she’d like to try something different. Dottie, who is always up to taste something different, backed up. The only thing she has discovered in her 72 years that she can’t bear is jackfruit. This aversion has something to do with a childhood memory of its pungent aroma.

The woman who offered this taste of something different was Eleanor Léger. What she was offering were tastes of ciders from Eden Specialty Ciders, the Newport, Vt., company Léger founded with her husband, Albert, in 2007 to make high-end alcoholic ciders. Standing behind a table with bottles and cans of cider, Léger asked, “Dinner, porch or dessert?” Looking with astonishment at a bottle labeled Brut Nature, Dottie said, “Dinner.”

Since we spit out everything we sample at a tasting, Dottie, with the bone-dry bubbles still swirling in her mouth, walked very quickly to find John and thrust her glass under his nose. And with that, the two of us walked back to Léger to taste her dessert option, a single-variety Ice Cider made from a historic variety called Northern Spy. It had a spicy nose and a nutty, caramelized, luscious taste with just enough acidity to hold it back from being too-too. The 2020 Northern Spy was aged in French oak Chardonnay barrels for a year after two years in stainless steel. It was bottled this year. We could taste the care.

John promptly pulled out his phone for a picture of Dottie and Léger and we vowed to get in touch. When we called the other day, we got a crash course in not just the making of alcoholic cider, but history and civics and what it means to be part of a community. It turns out that wines and alcoholic ciders have more in common than we could have imagined. Some of their ciders are single varieties and some are blends, sometimes with as many as 16 varieties. Some are made from heirloom (non-hybrid) varieties and mixed with some that are grown for their tannic structure and the acidity they bring to the blend. Some are rosé and some unfiltered, some are dry and others have varying amounts of residual sugar.

(Eleanor Léger and Dottie)

(Eleanor Léger and Dottie)

Some are field blends, estate-grown at their biodynamic orchard, where they have more than 40 varieties in about 1,000 trees that are nourished holistically with homemade compost and stuff like liquid fish. Eden’s lineup, which they later sent us samples from, has the fanciful names of apple varieties like Foxwhelp, a dry, piquant, hazy yellow cider that was great with Dottie’s rare salmon. One, Falstaff, has been aged for seven years in French oak barrels. The luscious Heirloom Blend requires more than eight pounds of apples to make a single bottle.

Léger, 60, told us that she and her husband, 62, tasted Ice Cider for the first time in Montreal and it blew them away. Why were they in Montreal?

“Albert is French-Canadian. Most of his family lives there,” she said. They immediately asked themselves, “Why is nobody making this in the U.S. I had left Corporate America and I was trying to figure out what I’m going to do with the rest of my life. It was a total mid-life crisis. And one thing led to another.” That’s an understatement. According to Vintus, Eden Cellars was the first producer of Ice Cider in the U.S.

Eleanor Léger has a bachelor’s in economics from Harvard, which she and Albert attended, and she has an MBA with distinction from the Wharton School. Corporate America translates as years as a management consultant and senior executive in the financial software industry. She shares her knowledge on her blog, Cidernomics.com. Albert has a doctorate from Johns Hopkins in chemistry. He became a research scientist but missed teaching young students and in 2015 returned to the classroom at Phillips-Exeter Academy, where for years he had been chairman of the science department. They have two grown up kids.

The Légers returned from Montreal and bought an old dairy farm in West Charleston, Vt., not that far from where her great-great-grandfather lived before the Civil War. It’s two hours from Montreal. She took a short course in cider production that Cornell University was offering and visited “a bunch of orchards,” learning a lot about apple varieties, and purchased used equipment from a small Ice Wine producer in Quebec and for a while had some enologists from Montreal come down to help them out.

(Eleanor and Albert Léger)

“The initial thought was, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to make some of this in our basement?’ And because I was unemployed at the time it became a much larger project than it would have been otherwise.” Much bigger. Eden is now an industry leader and Léger has chaired the board of the American Cider Association three times. It’s been an interesting journey, to say the least, as many small farms are struggling across the country.

“Because it takes a while to plant trees and have them bear fruit we were purchasing fruit from Day One,” she told us. “In the course of trying to understand the local orchards and what they grew and what was possible to do in terms of working with fruit from Vermont, we got to know these wonderful small orchards that and in some cases had historic trees—80, 90, 100-year-old trees with interesting varieties that you don’t find in grocery stores and nobody was paying them any money to keep them going. When we first started, we were buying fruit from Scott Farms. They’re like the museum of apple varieties. They have more than 120 different varieties. For fruit that they couldn’t sell to the co-op market, they were getting $12 a bushel. Over the course of the 10 years we bought from them, we ended up paying $25—happily, happily.”

In addition to buying from small orchards, they also work with large ones, like Sunrise Orchards, a Vermont wholesale apple company in Cornwall. “It’s been as much of a passion project to support them as to support Scott Farms because it’s not easy for anybody,” she said.

When the Légers started making their Ice Cider there were fewer than five alcoholic cider makers in Vermont. Now there are about 30, she told us. Their first Ice Cider, made in the basement from which they have since moved, resulted in 120 gallons. Before Covid, they had grown to 12,000 to 14,000 gallons, with their “sole focus” being selling to restaurants. But when Covid hit and those restaurants struggled and some closed, the Légers had to painfully pivot their business to go big into cans. That move pushed their volume to 23,000 gallons. The cans were our third option, “Porch,” it turns out.

All of the ciders, including the bubblies, the still ciders and the dessert ciders in bottles and cans, are distributed in around two dozen states and the District of Columbia. Along with a list of distributors on their site, the ciders are also available from the cidery and at the Shelburne Vineyard in Shelburne that Eden Ciders merged with in April to facilitate distribution and sales of each other’s products.

So although we would stop at U-Pick orchards when the kids were younger, we didn’t know much about apples. Turns out while they do well in cold climates, they also grow in Arizona, Arkansas, and Virginia, Léger said. “Apples are incredibly genetically adaptable. They have more chromosomes than humans. They’re cross pollinators so every seed is a genetic individual.”

The Légers pride themselves on using 100 percent Vermont-grown apples.

We were curious about how Ice Cider is made. In Canada, which is famous for its Ice Wine, the process generally starts with frozen-on-the-vine grapes. Apples are less delicate than grapes, she told us, so you can harvest and hold them for a while. So every year for years, they waited until it was super cold and they would press the apples and put the juice outside. Over four to six weeks, the juice would freeze and separate, the water rising to the top as ice and the sugars and acids, much heavier, would fall to the bottom. They would remove the ice cap and test for sugar concentration, brix, below. “We would generally save 22-23 percent of what we started with so 77 to 80 percent is ice,” she said.

(Freezing juice for Ice Cider)

Ouch! The economics of that sound tough, we said.

“It’s a fancy bottle at a high price and it’s delicious and compared to Ice Wine it’s still reasonable and with nice acidic backbones, you can have it with dinner,” she responded.

But climate change is making that process more difficult. Instead of the maybe six weeks they had for the freezing process, now they’re looking at maybe four days, she said. “We don’t measure but if we did it’s dramatically less. Now we’re reorganizing the way we’re thinking about making harvest. If the weather gets cold enough we’ve got to make as much as we can because we’re probably not going to be able to make it every year. It’s not so much the warming, it’s the temperature variations within a few hours.” The cold spell this past May that we wrote about here caused an extreme loss of crops also in Vermont, she said.

When they started in 2007, “cider was not a thing,” she said. “It was fresh juice at the orchard in the fall. Everywhere else in the world cider means fermented apple juice but in this country it changed because of Prohibition.” Then in 2011, Angry Orchard, which she described as a “mass-market made from concentrate” hard cider produced by Boston Beer, hit the market and “and expanded the category.”

Because by then they knew quite a bit about various varieties of apples, they kicked around the idea of making an interesting dry cider and that led to their Champagne method Brut Nature.

While McIntosh accounts for about 80 percent of the apples grown in Vermont, the uniqueness of the specialty apples and the varieties that can be foraged is what quickens the hearts of people like the Légers. They make a cider from what she called “wild deer-planted apple trees on our neighbors’ property,” which is just what that sounds like. “They have 200 of them and we found six that we really like and are starting to propagate.

“I think foraging is wonderful. It’s a chance to discover varieties. What we’re really excited about now is finding indigenous varieties that work in our climate that are disease-resistant because they’ve grown up and survived in our climate so they don’t need horrible things sprayed on them, so that’s really the focus of our foraging.

“But at the end of the day our passion has always been about supporting growers and keeping the Vermont working landscape growing and not developed into tract housing,” she said. “We need housing, we do need housing, but the working landscape, too.”

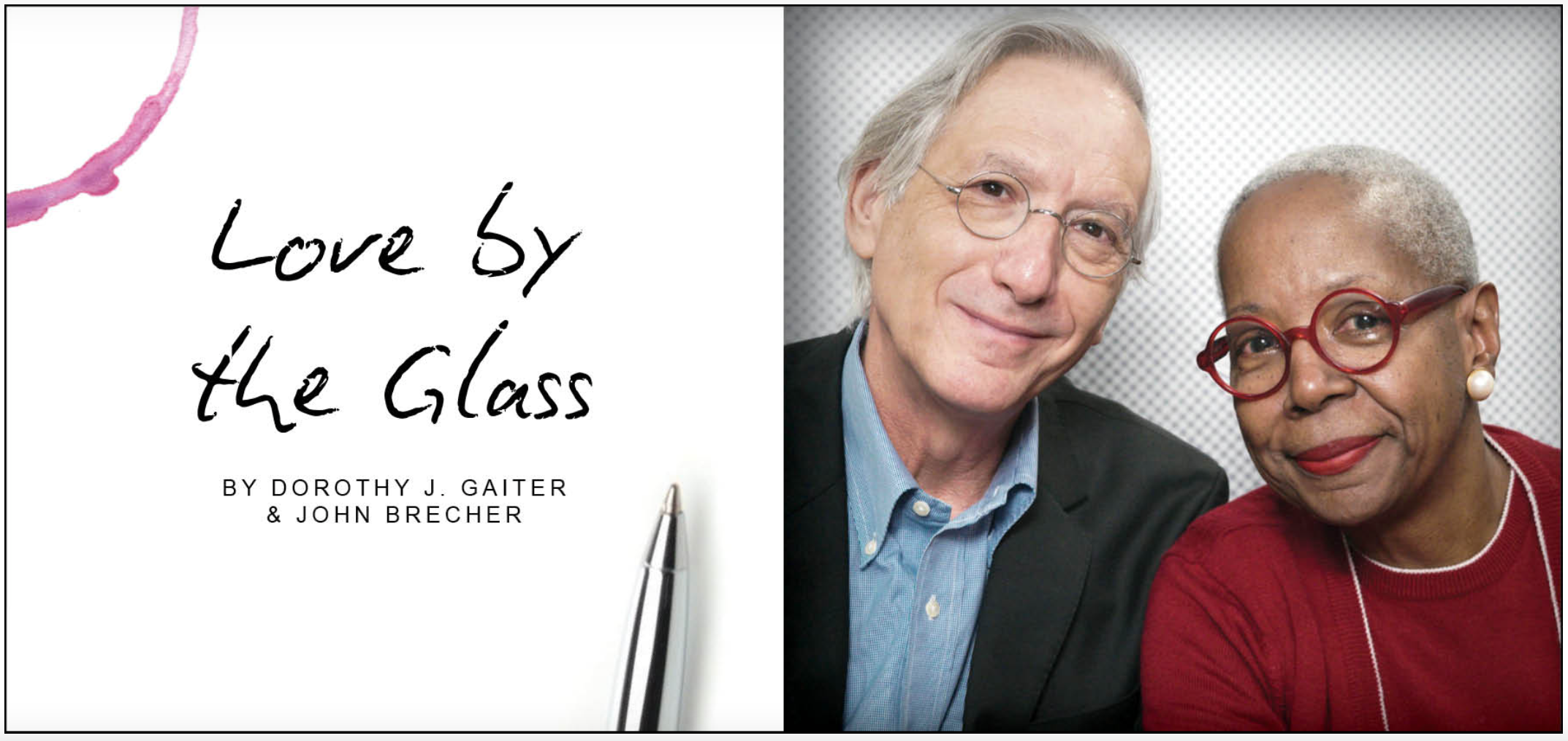

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett