The new year is always a good time to look forward as well as back and with Rosh Hashanah coming early this year, we thought we’d check in with Eli Ben-Zaken, one of Israel’s most revered winemakers. At a time when vintners across the globe have faced enormous challenges, he seems to have seen it all: war, heat, fires, climate change and COVID. What we wanted to know is: How does anyone stay optimistic anymore?

Ben-Zaken, 77, was born on Rosh Hashanah in Alexandria, Egypt, grew up in Italy and moved to Israel. He planted the first vineyard in modern times in the Judean Hills, west of Jerusalem, in 1988 and his first vintage of Domaine du Castel was 1992.

We first contacted Ben-Zaken at the end of 2018 when we were writing a column about the increasing prominence of the Petit Verdot grape. Ben-Zaken, with a great deal of effort, imported Petit Verdot vines into Israel after visiting Château Margaux in Bordeaux in the mid-1990s. In 2019, we met him when he came to New York with a group of winemakers who called themselves the Judean Hills Quartet.

Domaine du Castel, which makes wines from classic Bordeaux varieties, has received a great deal of international attention over the years, and rightly so. We described its Grand Vin as “pure bliss.” It produces about 400,000 bottles a year and about a quarter of that is exported. The U.S. is the biggest export market – France is second and the U.K. is third -- and we’ve seen the wines at some fine restaurants in New York. It appears to be fairly widely available at stores.

Ben-Zaken has turned over Domaine du Castel, which opened a new facility in 2015, to his children Eytan, 50, who is now the winemaker; Ilana, in charge of exports and acquisitions of equipment, 52; and Ariel, 48 and board chairman, who was born on Yom Kippur (“We covered the two holiest days of the Jewish calendar,” Eli told us). He has seven grandchildren. Eli moved back to the nearby original home winery, now called Razi’el winery, where he makes a red Rhône-style wine that is 60% Syrah and 40% Carignan.

All of the wines are kosher, so let’s stop here to say this: Outstanding wines are made in Israel these days (not all kosher) and, generally, if you think all kosher wines are bad, you are far, far behind the times. (Here’s Royal Wine Corp.’s explanation of what makes wine kosher.) Good kosher wines are being made all over the world. In Bordeaux, Château Malartic Lagravière, a Graves Grand Cru, has made some of its red as kosher wine over the years and, in 2019, produced its first kosher white. We asked its co-owner and winemaker, Jean-Jacques Bonnie, why he did that and how it was done. He wrote: “We started doing white kosher wine because our client expressed a need. We produced a kosher and a non-kosher white wine. The client has a need which is not the whole crop. Therefore, the client will only send workforce for the volume he needs. Nevertheless, the two wines are based on the same terroir, the same varieties and blend, and the same aging.” The wine costs $100.

Royal recently sent us Ben-Zaken’s 2018 Razi’el, the winery’s second vintage, and it was stunning. Too many Rhône-style wines, even from the Rhône, have the power we sometimes anticipate, but lack structure. This wine had everything and in balance. In our notes, we called it “a beautiful wine” with “finesse and elegance,” noting red berries, plums and black peppercorns, herbs and that Rhône tell-tale roasted quality. It is available at several stores in the U.S. for about $60. We need to say this, too: A wine like this should not mostly be available at kosher online sites or in the kosher aisle of the store. We came to embrace this so fully that when we weren’t specifically writing about kosher wines, we regularly included them in blind tastings along with non-kosher wines. Anyone who enjoys Rhône reds should try this.

Ben-Zaken said Raz’iel makes about 25,000 bottles and has plans to grow.

Everything seemed OK in January, Ben-Zaken told us when we talked to him over Zoom. COVID altered his business, but it was a balancing act. “It changed things. We lost some money from restaurants that went bankrupt, but very early we proposed to them to take back any stock they had so they wouldn’t have to pay for it. They were all closed at the beginning. So we lost money on those that didn’t recover. On the other hand, people drank more at home and probably also found it cheaper to drink expensive wine at home than at restaurants. By the way, the number of small wine shops that have opened in Tel Aviv is unbelievable. They popped up like mushrooms everywhere.”

In addition, as the blending of cuvées got underway in early 2021, “we created beautiful wines. We started the year very, very happy, winemaking-wise.”

The most recent fighting between Palestinians and Israelis began in May. The conflict did not directly touch Domaine du Castel or Razi’el, but at the same time it permeated everything. “Oh God, Palestinians and us. We have to find a way to live in peace,” Ben-Zaken told us. “Too much time has passed. It’s ridiculous to keep on fighting. Some solution has to be found and the sooner the better. I am very Zionistic and I have proven it by coming to Israel. I did a whole military career in reserves from simple soldier to retired major. I’ve proven myself. I’ve built a winery that I’m very proud of to show the world that good wines can be made in Israel. I think it’s time. We have to find a way.”

The heat waves started in May, too. “The problem is not how hot. It’s not the 36 degrees [Celsius] during the day. It’s the 26 degrees [76 Fahrenheit] at night. There’s no time for the grapes to cool. So the daily average is very high. I am exactly 50 years in the house and I never had so hot a summer.” Harvest is two weeks early this year. Ben-Zaken said climate change is “definitely, obviously” to blame.

And then the fires. In June, fire destroyed three hectares – about 7.5 acres – of Domaine du Castel’s and Razi’el’s 50 hectares. The grapes at this point were generally “green, pea-sized buds,” early in their development. Among the burned vines: Petit Verdot, although a different plot than the original one. Smoke taint from the fire also ruined about 70 tons of red grapes, about 20 percent. Ben-Zaken said it will take seven years to fully replace those vines. As it happens, those three hectares were among the first Ben-Zaken and his family had farmed organically. He still hopes to have all of the vineyards organic in about five years.

(Eli and his sons, Ariel on the left, Eytan stooping, examining the damage from the fire in June at Domaine du Castel.)

“It’s not about the certification,” he told us. “It is my worry that the soil we leave to our kids and grandkids should be better than the one we inherited.”

There has been some speculation in Israeli media that the fires were deliberately set. “It’s a possibility,” Ben-Zaken said. “Our problem is that you cannot insure a vineyard against fire. If it’s not arson, then the government doesn’t pay anything. We are still unable to get from the fire department a statement saying that it was man-made – even if not purposely, maybe by leaving a campfire.”

A second, smaller fire broke out in the region a few weeks later. And then, in August, yet a third fire hit suddenly, very close to Ben-Zaken’s original site in Ramat Raziel, the site of first vineyard and home, where he now lives.

The last fire “came very quickly and the police asked everybody to evacuate and workers from the winery came to tell me to evacuate and I said no way.” It came very close to the house. Ben-Zaken shared photos of himself with a giant water hose in the street. “We started hosing everything and we just managed. The fire passed on the border of the garden. It came very close to the winery, about 30 meters from the winery.” The winery and home were saved.

It seems so overwhelming to us. And now he has a new harvest – new grapes to pick, new wines to make. How can he – or any winemaker – keep doing it?

“We’ve had worse,” he told us. “In the second Intifada in 2002 or 2003, there was a period where we doubled our production because new vineyards came into production and there was an economic disaster in Israel and we had wines from three vintages to sell. Even if I’d sold the house, I would not have covered all the money I owed. Now that we’re economically established, it hurts but it’s not the end of the world…

“People who work the land have to be optimistic. New harvest, new hopes. Harvest is when you think about what you’ve done and what you might do differently next time. People sometimes ask me what’s new at the winery. It’s not a fashion show. We don’t make new clothes every year. But we make a new vintage every year and that’s what’s new.”

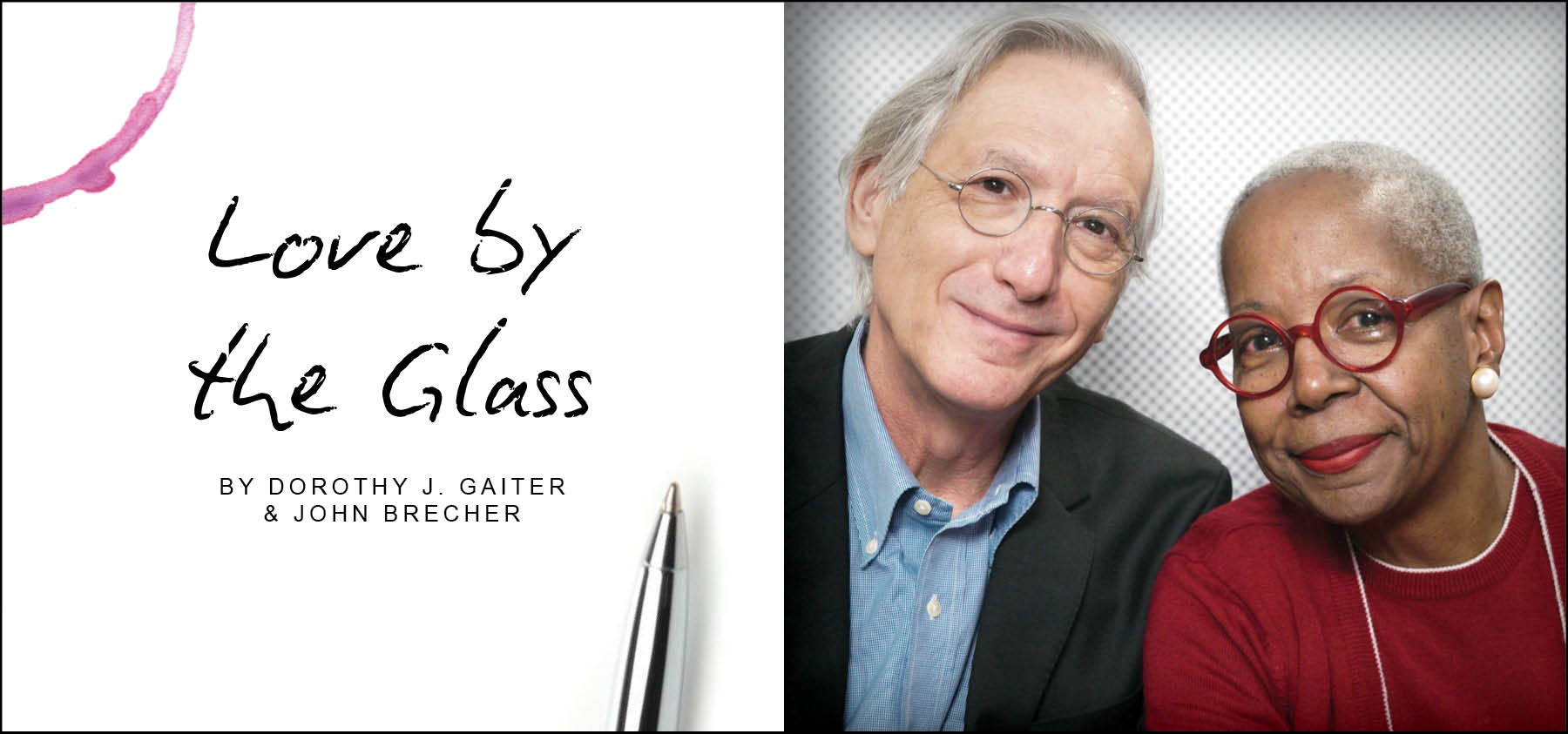

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett