We hopped the M10 to attend a tasting in Harlem recently. We had no idea the bus would transport us to a different time.

We were on our way to sample wines from Chile. Among the wineries represented, one named Santa Rosa de Lavaderos, from the Maule Valley in central Chile, was offering a vertical – 2018, 2020, 2022 – of its País. País? We rushed over.

The first two, which were blended with some Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah, were very good (and a great deal at $20). The 2022 was a barrel sample and it was delicious – lively like a good Beaujolais, but with even more pop. It was 100% País. The winemaker, Paul McRostie, told us his family has a small plot of 100-year-old País among its vineyards and he began to experiment with it several years ago because of its historic nature. He said his grandparents used to buy it in 15-liter returnable containers covered in wicker mesh. “It is our responsibility to act because there are no more old País head-pruned vineyards in the world,” he told us.

The first two, which were blended with some Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah, were very good (and a great deal at $20). The 2022 was a barrel sample and it was delicious – lively like a good Beaujolais, but with even more pop. It was 100% País. The winemaker, Paul McRostie, told us his family has a small plot of 100-year-old País among its vineyards and he began to experiment with it several years ago because of its historic nature. He said his grandparents used to buy it in 15-liter returnable containers covered in wicker mesh. “It is our responsibility to act because there are no more old País head-pruned vineyards in the world,” he told us.

(Dottie with Paul McRostie)

But the first two vintages he made weren’t really drinkable, he said, because the grape is challenging. It can be too acidic or not acidic enough and the tannins, unless carefully monitored, can be rough. It also has thin skins and the wines tend to be very light red. He kept at it.

McRostie said he didn’t know if he would blend the 2022. We knew we’d have to get back to him on that. And we also knew it was time for us to learn more about the current state of País (pronounced something like pie-eez). The journey ultimately took us from the middle of Chile to an urban winery in Los Angeles – but we started, of course, by buying a few bottles of Chilean País.

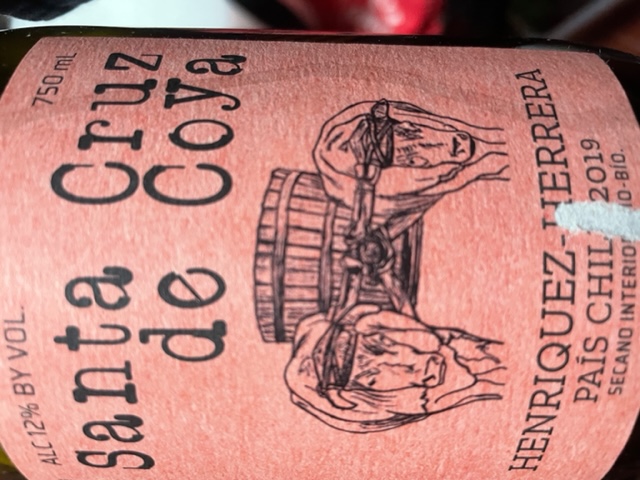

They were … particular. All four had very light color, closer to today’s orange wines than a red. They had a certain rustic quality, with some black pepper and earthiness. But they were all quite different. Dottie said of one: “This is a weird-ass wine,” which is an unusual tasting note for us. Our favorite was Roberto Henriquez “Santa Cruz de Coya” 2019 from Bio Bio Valley ($25.99). “Fresh-squeezed grapes. Some pomegranate and a little eucalyptus,” we wrote. “Utterly charming, with a nice touch of herbal bitterness. Really savory.”

País is one of those grapes that was long prized more for its productivity than its quality, but now is experiencing a rebirth of sorts. Last year, we wrote about Schiava from Italy, for instance. País, known by other names in other places – Mission in the U.S., Lístan Prieto in the Castilla La Mancha region of central Spain -- was brought to Chile in the 16th century by Spanish colonists. It was the first vitis vinifera planted in the New World, Mexico in the 16th century, and was planted in California in the 18th century, becoming the backbone of the California wine industry.

País is one of those grapes that was long prized more for its productivity than its quality, but now is experiencing a rebirth of sorts. Last year, we wrote about Schiava from Italy, for instance. País, known by other names in other places – Mission in the U.S., Lístan Prieto in the Castilla La Mancha region of central Spain -- was brought to Chile in the 16th century by Spanish colonists. It was the first vitis vinifera planted in the New World, Mexico in the 16th century, and was planted in California in the 18th century, becoming the backbone of the California wine industry.

It also became Chile’s most popular wine. As late as 1996, according to government statistics, it was the most widely planted variety in the country, before it was often replaced by international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc. Much of what Spain grew, except for in the Canary Islands, was killed by phylloxera in the 19th century.

País seemed destined to be forgotten. But starting around 2007, a small group of Chilean winemakers decided País, with its very old vines, was worth saving. Among them was giant Spanish-owned wine enterprise Miguel Torres Chile. Eduardo Jordán Villalobos, chief winemaker and technical director there, told us by email: “We decided to work with the País variety because of our conviction of how important heritage grapes are, of the history behind it and because of the long time they have been in Chile….

“We carried out many tests to achieve the potential of the variety for this type of wine, since it is a variety that can lose acidity quickly at the time of maturity and produce bitter tastes if it is not handled well…. It is a variety that needs specific soil and climate conditions to produce quality grapes.”

País is largely grown by small producers in Chile’s granite-rich soil and Torres supports them, not just buying their grapes but giving advice. We asked why Torres would work with competitors. “These centuries-old País vines have been important to the life of small producers,” Jordán wrote. “We have never seen the small producer as a competitor -- on the contrary, it is a contribution to achieve what we do since it gives us a unique product, from centennial plants cared for in a special way. That producer who has been forgotten and who has no options to sell his grapes at a good price due to the distance or lack of resources is the one we want to support.”

Torres made its first País in 2011 and also makes a sparkler called Estelado Brut Rosé – the first traditional-method País bubbly, it says.

Our journey made us curious about Mission. It’s impossible to overstate Mission’s role in America. It was planted initially in America by missionaries principally for sacramental wines. In some communities, cuttings were made available to those who wanted to make an everyday table wine. Eventually, as tastes changed, other Old World grape varieties that were less rustic replaced most of the Mission. Over the years, we have tasted all kinds of American wines – Dottie’s mother made Scuppernong – but we don’t think we’d ever seen a varietal Mission. According to USDA figures, there were only about 400 acres left in California by 2020. We went looking for one and that’s how we found Adam Sabelli-Frisch and his Los Angeles County winery, where he has made Mission since 2018. It’s his signature grape.

Our journey made us curious about Mission. It’s impossible to overstate Mission’s role in America. It was planted initially in America by missionaries principally for sacramental wines. In some communities, cuttings were made available to those who wanted to make an everyday table wine. Eventually, as tastes changed, other Old World grape varieties that were less rustic replaced most of the Mission. Over the years, we have tasted all kinds of American wines – Dottie’s mother made Scuppernong – but we don’t think we’d ever seen a varietal Mission. According to USDA figures, there were only about 400 acres left in California by 2020. We went looking for one and that’s how we found Adam Sabelli-Frisch and his Los Angeles County winery, where he has made Mission since 2018. It’s his signature grape.

We called him to ask why. He said he was attracted to its historic stature and important place in America. “It came with Cortés and those guys on the ships and spread its way up. I always love an underdog but I didn’t actually know if it would make a great wine in California because I hadn’t had that many. But I had had a lot of South American ones and they were all very promising, so I thought I can’t f--- this up too much. At worse it will be a bland wine that is maybe not the best wine in the world but it turns out it’s a very rewarding grape to work with.”

He buys his grapes from Somers Vineyard in Lodi. “Some of those vines are eight feet tall. They’re huge. And they really crop heavy. You could kind of see why Hernán Cortés and those guys put it on a ship to go across the Atlantic, because it was sturdy and it can take a beating. It was probably just a practical choice rather than anything else.”

He said it has to grow in the right places and be picked just right or it can be flabby and-or bitter. He discussed “Campari-like notes” that can be positive or negative depending on how strong they are. Not only that, he said, but it can be a confusing wine. “When people looked at the color, they said oh this is a light wine and it kind of is but it kind of isn’t. It’s got more punch than the color would indicate. So they got confused a little bit about what the hell is this.”

Given all that, then, we asked if it’s difficult to sell his Mission – he offers four, including an Angelica dessert wine – and he said: “It’s my best-seller because you can tell the story about it. The wine market has changed a little bit. You tell the history of this and how it’s an underdog and how little of it is left in California from being so widely grown – you can sell the story.” As we recently wrote, the new generation is interested in a good story.

We ordered his Mission wines and he has quite a mission statement, as it were, right on the label, which includes this: “The oldest grape in California, it has been mistreated and neglected for over a century. But there would be no wine in California had it not paved the way for all the others, so I’m eternally grateful I get to be part of its new dawn. I’m obsessed with this varietal…”

We found each of the four we tasted to be slightly different, but all to be distinctive. The two from 2019 alone, grown in the Mokelumne River AVA in Lodi, showed us how very different these wines can be from each other. We wrote of the 2019 “La Malinche” ($29): “Light color, almost like a light strawberry wine. Pinot-like earthy fragrance but some bitter Campari on the nose. Taste is peppery. Also reminds us of those little round almond cookies we used to have. Good acidity and tannins. Not like anything else, with black pepper, lots of herbs. Dottie thought it would go great with sardines. It kind of has a cocktail vibe because of the smells and tastes. But it’s light on its feet, even with all of those tastes.”

Then we had a curveball with the 2019 “Hernan” ($32). It seemed slightly oakier and therefore a little more familiar, with calmer herbs and less bitterness. Early on, we liked the first better. But then we had the “Hernan” with dinner – herb-garlic pork – and it rocked, adding just the dash of black pepper and hint of sweet fruit that made the dish even better. Dottie, though, still favored the “La Malinche” for what she termed “its purity.”

All of this made us circle back to Paul McRostie and his family in Chile to find out if he had yet decided whether to blend the 2022 or leave it 100% País. “I am not sure,” he said. “I tried the wine from the barrel a couple of days ago and it had lost some of the freshness and fruit aromas compared to what you tasted. But at this stage wines change very fast and can be unpredictable. I will decide before bottling.”

He added: “I only made País so far from the vineyards of my family (established at least as far back as the year 1900, according to official records). You can see they are really old plants and they have low yields. They are almost dry farmed and have small berries. Right now I am talking with my aunt and family because they are seriously considering replacing them,” though he hopes to talk them out of it.

So move fast, folks! We’d urge you to look for a País from Chile or a Mission from California (and we’d say younger is better and serve with a chill). Will País/Mission catch on? We can see in searches that every couple of years, it gets some attention and then slumps again, so we kind of doubt it will ever be The Next Big Thing. But we’re pulling for it. Here’s to the underdogs.

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett