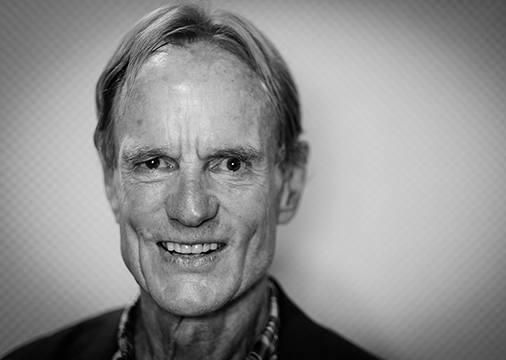

Richard Sanford is a legend – but, as with so many legends, his story includes painful setbacks. Sanford, 77, with his then-partner Michael Benedict, proved that Santa Barbara County is a great place to grow Pinot Noir. By extension, they amplified what other visionaries like Martin Ray had discovered: that California could produce its own world-class wine from that grape when grown in the right place. Without them, the now-famous Sta. Rita Hills viticultural area might not exist, not to mention “Sideways.”

Sanford was a Naval officer during the Vietnam War. He returned scarred by the war and, even more, by the hostile reception veterans received at home. As luck would have it, a shipmate named Scott Wine had introduced him to Volnay, the fine Burgundy. Returning home, Sanford wanted to do something close to nature. He’d studied geography in college, remembered that Volnay and decided to find a spot where he could make a Pinot Noir that could rival Burgundy. “That created a threshold for me in wine,” he says, “and I thought to myself, if I could be involved in something that had that sort of texture and beauty, why wouldn’t I do that?”

“I looked at Napa and said, if I plant a vineyard next to a neighbor in Napa, I'll probably be making wine same as my neighbor or similar. But I was interested in Pinot Noir and I thought, I’ve got to go find the place to make quality Pinot Noir,” he told us recently.

“I looked at Napa and said, if I plant a vineyard next to a neighbor in Napa, I'll probably be making wine same as my neighbor or similar. But I was interested in Pinot Noir and I thought, I’ve got to go find the place to make quality Pinot Noir,” he told us recently.

He and Benedict found investors and, in 1971, planted the first Pinot Noir vines in Santa Barbara County, in the cool-climate Sta. Rita Hills, in the east-west traversing Santa Ynez Valley. Sanford & Benedict’s first vintage, the 1976, was a sensation. We’ve been fans for so long that we opened a Sanford & Benedict from the ’70s from our cellar for Open That Bottle Night in 2012. The partners separated, apparently not on great terms, in 1980 and Sanford opened his eponymous winery in 1981, with money from the sale of his share of the Sanford & Benedict winery and the vineyard, which continues to be a world-famous source of grapes. Sanford ultimately lost control of Sanford Winery, too, at least partly, he says, because investors in that winery didn’t support his commitment to organic farming.

He and his wife, Thekla, started Alma Rosa Winery & Vineyards in 2005, in the Sta. Rita Hills appellation. They sold it in 2014, after bankruptcy. He describes his role there now as “cheerleader.” But it’s clear he works closely with owners Bob and Barb Zorich and Nick de Luca, whom Sanford said he chose to be the winemaker, on all aspects of the operation. (He’s very excited about a new vine-pruning technique.) The winery produces about 8,000 cases a year. The Alma Rosa Pinots, especially the vineyard-designated Pinots, are rich and pure; the Chardonnays are focused, with great presence, and could make even skeptics believe again in California Chardonnay. The wines cost about $32 to $65.

In 2012, Sanford became the first winemaker from Santa Barbara to be inducted into the Vintners Hall of Fame by the Culinary Institute of America at Greystone. We sat down with Sanford at Grape Collective to talk about where he – and California winemaking – are now and where they might be going. Sanford is a deeply reflective man. The questions and answers have been compressed and edited for space. Read the full interview here.

Grape Collective: You’re a famous winemaker, but clearly the financial side has been difficult.

Grape Collective: You’re a famous winemaker, but clearly the financial side has been difficult.

Richard Sanford: It’s been a very challenging business, particularly starting with no money. I’ll always remember when I started out people said this is not a very good idea. From the very, very beginning, farmers said grapes won’t grow here. It was really challenging and interesting to start a new agricultural crop. It was a bit of a threat, and it was unusual. It took some effort to overcome the negativism. There was one person who said this is a good idea, and that was enough for me. I knocked on a lot of doors to try to find some investors because I didn’t have the wherewithal to do any of this. My investment was sweat equity.

When I started out I was doing all the work myself and that was important to me because I developed a connection with nature. That connection was healing for me. I developed an interest in Eastern philosophy. And I think that’s made me better as a winemaker to learn to stand off and be in nature and allow nature to take its course. But all along we needed funding. I wasn’t a business person. I had to learn about spreadsheets and that kind of thing. And debt was something that really overcame me during the recession. It’s been the activity in the vineyard that’s really saved me, that sort of spiritual connection.

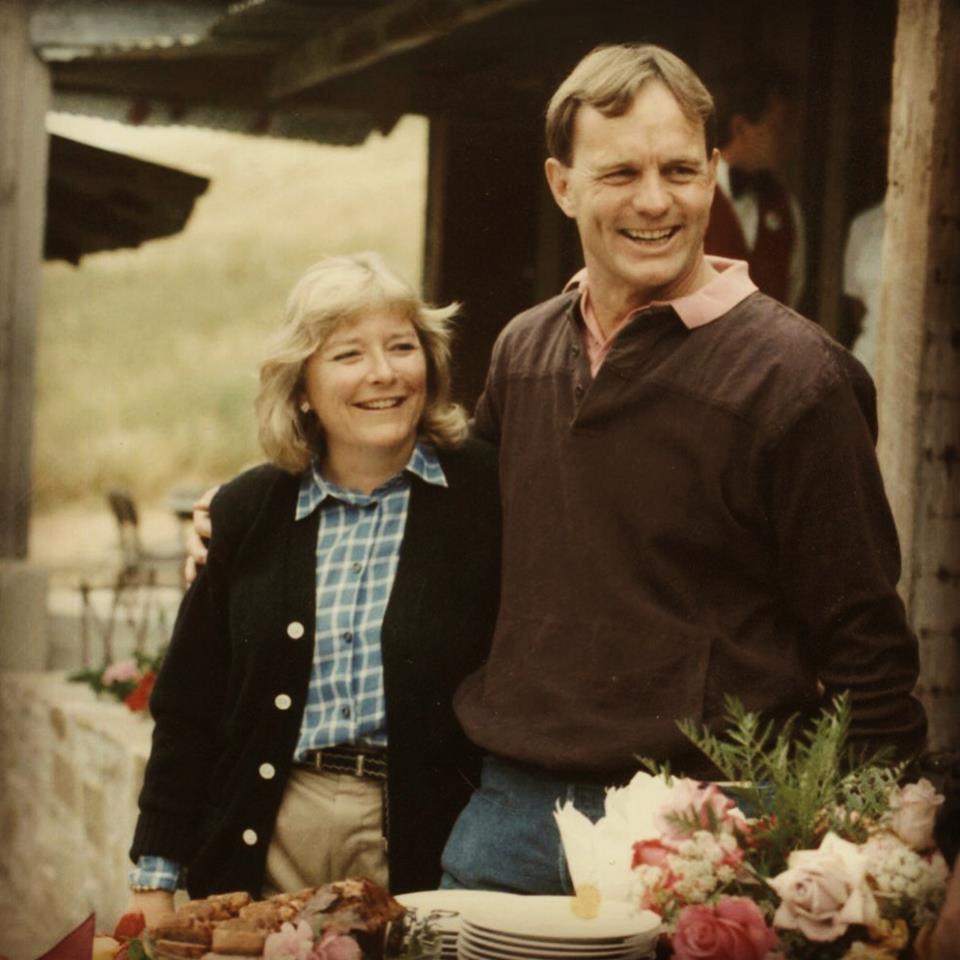

(Photo: Richard and Thekla Sanford in 1985)

Selling the Sanford & Benedict vineyard must have been tough.

There was a piece of my soul there. I would go down and visit the vineyard and finally Thekla, my wife, said you’ve got to give it up, it’s becoming an obsession. It really was.

But then you started Sanford Winery.

With the proceeds from selling Sanford & Benedict, I purchased the new ranch and planted vineyards and got started as Sanford Winery and took on considerable debt to do so. Things were going very well. We were going up to 50,000 cases of production. After building the winery of my dreams – I spent entirely too much money, it ended up being $10 million – these were the days we were selling $5 million of wine every year. I thought, gosh, this is a pretty big deal. We’re able to do all of this. After building the winery and having to take on additional debt, I went out and found a partner [the Terlato family]. That turned out not to be a good decision for me. That became a very challenging time.

My wife and I left Sanford Winery to pursue winemaking organically. I’m proud that we were the very first organic vineyard in Santa Barbara County [the El Jabali vineyard] and continue to be certified organic.

When you first embraced organic farming, that seemed almost radical.

My wife had come from Wisconsin and her grandfather had a dairy farm. They did all their agricultural farming organically and she said, Richard, why don’t you just grow all the grapes organically? I was fearful. I said, “I don’t know that’s possible.” But after a couple of years I tried it out and sure enough we weaned ourselves off all chemical herbicides and pesticides.

Is it difficult to farm organically?

You just have to be inventive. I remember having a mealy bug problem and then I learned that the ants were farming the mealy bugs for their nectar and then I thought we have to get the ants under control. Diatomaceous earth, if you can get the ants to eat it, binds up their innards and it’s a great way to get rid of ants but they have to eat it. So then I had to figure out if the ants wanted to eat sweet or protein. So there I was with a No. 10 can of jelly mixing in diatomaceous earth and a whole big can of peanut butter mixing in diatomaceous earth. So I had one row I would spread peanut butter on the bottom of the vine trying to get the ants to eat the diatomaceous earth and I learned that they indeed like sweet. You just do what you have to do to try to figure it out. It’s a lot easier just to spray.

If we said to you that your Chardonnays remind us more of Chablis than of California Chardonnay, would you consider that a compliment or a dis?

If we said to you that your Chardonnays remind us more of Chablis than of California Chardonnay, would you consider that a compliment or a dis?

That’s a great compliment. Thank you. There was period of time when Chardonnay became just so over-oaked it was just not drinkable and I remember that time and thought we’ve got to get beyond this. I stopped drinking Chardonnay. It was just too heavy-handed. Chardonnay growing in warmer climates develops that flabby, almost soapiness with the lack of acidity. We have these beautiful bright acids in our area. We work with natural acids. There’s no better acid in wine than the grape acids.

Just this year, two classic Napa wineries, Heitz and Stony Hill, were sold by the families of the founders. Is there a future for small, family-owned wineries?

I think it’s hard in our country for family dynasties to be in the wine business as it is in Europe. The tax issues and inheritance issues and that sort of thing. I think it’s very challenging. Sadly, I don’t think we’re going to have these long-term wine families the way the Europeans do. I see so much being owned by investment funds now. An investment fund doesn’t have the same empathy to wine that we might have and I think that’s hard long-term – hard for our culture and hard for the planet.

Could you do what you did if you were starting out today?

Boy, that would be tough because of the cost of land. It requires funding. Planting a vineyard these days is a $50,000-an-acre kind of thing

And then you have to sell the wine.

The deep-pocket people who come into the business think that it’s a slam-dunk kind of deal. You spend a lot of money and then you’re in the wine business. Well, then you have to sell the wine and you have to have representation and there are so many wines in the marketplace now. Who needs another wine in the world? But there’s always a place for quality.

What do you think of the future of Pinot Noir?

It just gives me chills to think about Pinot Noir because a beautiful Pinot Noir, a beautiful Burgundy has just so many parts to it. It’s that lovely. Often, our wines are blueberry and sometimes blackberry, and there is beautiful structure to fine Pinot Noir that has great length. We haven’t been able to achieve a Comte Georges de Vogüé 30-year aging Pinot Noir that’s so luscious, but we’re getting there. And I think with our older vines I’m recognizing that now that we have 35-year-old vines that we have a structure to the wines that are more complex now. The future is very bright for Pinot Noir. Our region has just exploded in growth. What gives me huge satisfaction is seeing some very talented young winemakers coming into our region and focusing on our region as where they want to make their statement in wine.

Would you like to name some?

Well, you know Jim Clendenen has been in our region for a long time and has done a masterful job. Adam Tolmach at Ojai Vineyard has been doing a nice job. Rick Longoria is older. Not a young one, but you know, Gavin Chanin.

Young kid.

Very young guy that is very talented. At Tyler, Justin Willett is making fabulous wines. There are a number of them that have chosen to come and make this their place. I'm concerned that pinot noir is being priced out of the ballpark.

Do you think you’ll ever retire?

Do you think you’ll ever retire?

Can’t afford to! No, I’m very lucky to have found something that resonated so well with me in my lifetime. I’m 77 and I look forward to being in the vineyard, look forward to tasting the wine and being involved.

It’s clear that your wife, Thekla, has been your closest adviser and partner throughout your career.

Thekla came along in 1976, just as we were doing our first vintage. So she’s been an important part of the whole thing from the beginning.

You’re celebrating your 40th wedding anniversary this year. What’s the secret?

Oh, boy. To be humble and to be open, and love is so important. And the lack of possessiveness is important. To be open to the possibilities. It’s been hard. It’s been particularly hard because of our financial situation and it continues to be. There’s no getting around it.

You seem like a man at peace.

Yeah, what can you do? That's all you have, particularly with the storms that we've weathered. I think the important thing is to get over our own self-importance, to get over ourselves, and look toward other inputs, other benefits, other than ego. Super egos ruin so many people. But that’s the challenge of being human, isn’t it? You know what I feel best about? I’ve never compromised my values in all these years of doing business and winemaking. There are ways to be in this world responsibly and we’ve chosen to do that.

--

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Read more from Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher on Grape Collective

Banner by Piers Parlett, video edit by Max High-Cuchet