When was the last time anyone said to you, “My favorite wine is California Chardonnay”? Millennials love their Malbec, boomers love their Bordeaux and Burgundy and geeks like us love their Riesling. But California Chardonnay?

Well, yes, actually. While many people might not admit it, Chardonnay, and especially California Chardonnay, continues to be America’s favorite variety, according to the Wine Institute. We certainly understand why, since it was our first love when we started drinking wine. The problem is that too many American Chardonnays at the low end became watery, insipid and unreal. And at the high end, which has become very expensive indeed, they are too often heavy, alcoholic, overly oaked and sweet. Still, if you are entertaining anytime over the next few months or taking a bottle of white to dinner, it’s hard to go wrong with Chardonnay and especially Napa Valley Chardonnay because of its popularity. Is that possible at a reasonable price? We found evidence that it is -- and we were determined to get to the bottom of this to discover the lessons.

It all started with a bottle of Trefethen Chardonnay 2019 from the Oak Knoll District of Napa. We’ve been fans of family-owned Trefethen for a long time. We visited the winery in 1976 and met John and Janet Trefethen, proprietors of the historic winery, which is now overseen by their children, Lorenzo, 38, and Hailey, 35, the third generation. We recently opened the 2019 that the winery’s representative sent us and it was simply lovely. It tasted like grapes, not like nutmeg, oak or sugar. It had the kind of balanced acidity that made us think it would age well. It paired beautifully with food. And we found it widely available for about $29.99 (we bought three bottles at that price and plan to hold onto one for a long time). Winemaker Bryan Kays made 15,200 cases of the 2019.

(Photo credit: Will Bucquoy)

Here's our question: If Trefethen, in Napa Valley, can make this wine at this price, why can’t we find more like this? We called John Trefethen to find out. (We’ve been speaking with him about his Chardonnay for years and some of his comments here come from an earlier interview we had with him about the ageability of California Chardonnay.) Trefethen Chardonnay’s international success was also helped by the late Steven Spurrier, who organized the Judgment of Paris blind tasting in 1976 during which two Napa Valley wines topped famous French wines. Spurrier, who died in March, would have turned 80 on October 5th.

A lot of credit for Trefenthen Family Wines over the past 53 years must go to John’s parents, Catherine and Eugene Trefethen, an industrialist, conservationist and philanthropist, who bought the initial winery in 1968 when it was known as Eshcol Winery, and five adjacent farms, about 600 acres total. The purchase was conditioned upon passage of the landmark Napa Valley Agriculture Preserve and proved that limiting development to agriculture was attractive to moneyed conservation-minded people and would not depress land values.

In 1968, there were fewer than 30 wineries in Napa. John Trefethen, now 78, the founding president of the Napa Valley Grapegrowers and an early president of the Napa Valley Vintners, also extols the virtue of the land. Of the 440 acres of vineyards they farm sustainably, about 30 percent of it is Chardonnay in the cool-climate Oak Knoll AVA, which Janet helped get approved. The 440 acres are broken into 49 vineyard blocks with distinctive soil types, divided again into 120 irrigation blocks so that water can be delivered where it needs to be and when.

“We’re making wine true to the vineyard and we’re letting the vineyard speak as much as we can and we try to enhance it a little. We started with the most basic information and equipment, the most basic. It’s all about the grapes, whoever is growing the grapes,” John told us when we called the other day.

His parents’ idea was to sell grapes from their replanted vineyards to winemakers and they did that for years. But John started tinkering with winemaking, first in his parents’ basement. It wasn’t very good wine but he got better. In 1973, he and Janet made their first commercial releases, among them a Chardonnay and a Pinot Noir, from the family’s estate vineyards. For five years, he said, the folks at Domaine Chandon made their wines at Trefethen, so they had a lot of stainless steel tanks. “We weren’t fermenting in French barrels. We had some to do aging but we were very, very careful of the new-winery-barrel-syndrome. You buy new barrels and they’re new and the time from too little to too much is like three days,” he explained. “We spent a lot of time resisting pressure to turn the wine into a bigger, riper, more malo wine. All that stuff that the New World went through, that California went through, that Australia went through.”

Observing how the French preferred their wines to be made “influenced my winemaking a lot,” John said. “Theirs were lower alcohol when making their still wine, very acidic. They blended a lot.”

Trefethen’s 1973 Chardonnay was popular. “I guess we were doing something right. We decided we could use that as a base and then just do a much better job, make it more elegant.

“There weren’t any clones in 1973,” he recalled. “There were cuttings from Wente and Martini and you went and got your own cuttings and you sent your crews out and looked at other people’s vineyards and those that looked good and were producing good wines, you got cuttings of those.”

Now, they have 13 clones of Chardonnay and work with 28 combinations of clones and rootstocks to get to a blend they like. The vineyards are different now, too, as they’ve learned and technology has made more things possible. “We have nine rootstocks in the vineyards, a large variety. We purposely plant Chardonnay in a number of soil types, not just what is recommended. We’re looking for diversity and interest within that diversity. A few years ago we did a retrospective tasting of all of the Chardonnays back to the ’70s and there were an amazing amount of the total that are just good, sound structured wines.”

Then came the 1976, the Chardonnay that made them famous internationally. “It was that marvelous time when everybody was challenging the world a little bit. The 1976 was made very much in the classic style, not the kind of early California style, which had a lot of oak. It was more a classic European style.”

Unknown to the Trefethens, Patricia Gallagher, an American who was a director at Spurrier’s Académie du Vin in Paris, had come up with the idea of honoring the U.S. Bicentennial by holding a friendly competition between French wines and wines from California. On a Zoom earlier this week to discuss the Académie Library’s new book, “On California,” Gallagher hailed Spurrier and George Taber, who reported the astounding results in Time magazine, for embracing her idea and “taking it around the world,” referring to the fame of the event, the recreations of it and the confidence it gave winemakers in other regions to reach for the stars.

She also said she told Spurrier that they should go to California because the wines they would find there would be better than the selections found on shelves in France, some of which, she said, caused her to “look away” in embarrassment when she served them to the school’s students. On May 24, 1976, the wine world turned upside down, with the 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay made by Mike Grgich winning the white wine competition and the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon S.L.V., made by then-owner Warren Winiarski, the red wine competition. Winiarski was also on the Zoom call.

Back in Napa, “We were just blown away because we didn’t know the competition was going on,” John told us. In 1979, with the French still smarting from the outcome of the competition, the French publication Gault & Millau Nouveau Guide staged a competition among 330 wines from 33 countries. It was called the World Wine Olympics. Trefethen's 1976 Chardonnay “won the Chardonnay tasting and was judged best in the world,” John said.

“It was such an upset that Robert Drouhin challenged everyone to a rematch. The next year, they held another competition, put some pretty fines wines in there, too. And we won again with the 1976,” John told us. On the Trefethen website, it says, “Drouhin’s 1976 Pugligny Montrachet finished a statistically significant second. Convinced by the result, Robert Drouhin said Trefethen Chardonnay was ‘the yardstick by which all other Chardonnays must be measured.’”

Napa Valley Winemakers: Janet Trefethen from Christopher Barnes on Vimeo.

One thing was a puzzle to the Trefethens for years. Janet, who kept track of all of their winery accounts, could find no sale of their wine in France, so how did the wine make it into the World Wine Olympics? For years they thought perhaps their French friends from Domaine Chandon helped. But in 2018, at a celebration in London of Trefethen Family Wines’s 50th anniversary during which Janet and Lorenzo talked about the Chardonnay’s miraculous win and shared some of that wine, Spurrier, a longtime family friend, said he was responsible for the wine’s entry. He was a friend of the family’s UK importer and a judge at the wine Olympics.

In August 2020, we Zoomed with some of the women of Bacigalupi Vineyards in Sonoma, which not only grew the grapes of one of our all-time favorite Chardonnays made by Belvedere Winery, but also, we learned last year, provided almost half the grapes Grgich used to make Chateau Montelena’s winning wine. Since 2011, the Bacigalupi family has been making wine under its own name. When Grgich realized the quality of the grapes he had purchased, he tried to arrange to buy the next vintage, but it was already under contract to another winemaker, Pam Bacigalupi told us.

Which brings us back to Trefethen and the beauty of its ownership of its vineyards. The vineyards are grown sustainably and they sustain over generations.

“We had a vineyard that we thought was going to be special and it is,” John said, reflecting on the early days. “The Chardonnays are beautiful wines and they last and one of the problems we have is when people started releasing their wines sooner -- maybe a cash-flow decision -- we were always later because they weren’t ready. We’re always a vintage behind the industry. It took some time to mellow in the bottle and that still is the case. It’s bad for my sales but it’s great for the wine.”

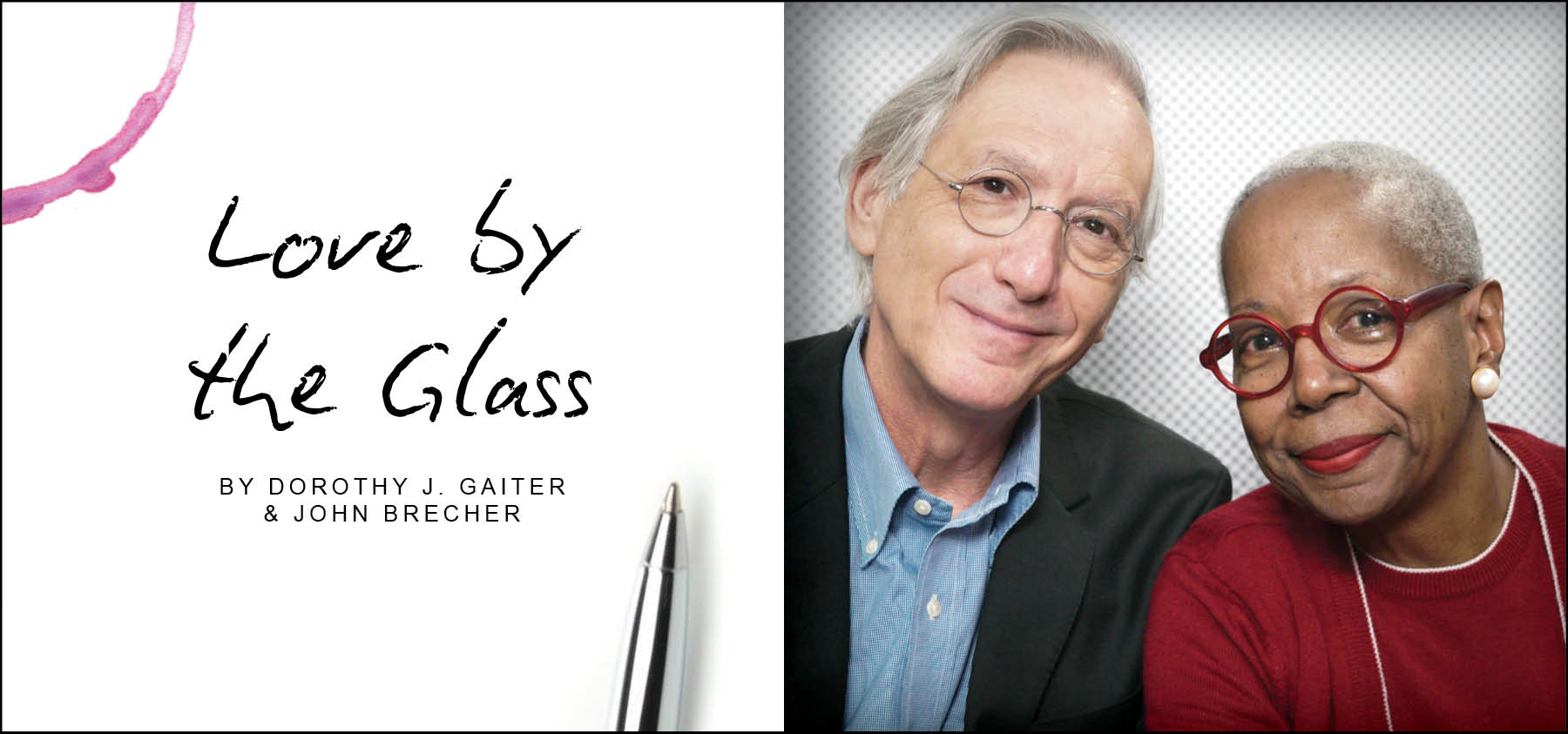

Dorothy J. Gaiter and John Brecher conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010. Dorothy and John have been tasting and studying wine since 1973. In 2020, the University of California at Davis added their papers to the Warren Winiarski Wine Writers Collection in its library, which also includes the work of Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson. Dottie has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald, The New York Times, and at The Journal. John was Page One Editor of The Journal, City Editor of The Miami Herald and a senior editor at Bloomberg News. They are well-known from their books and many television appearances, especially on Martha Stewart's show, and as the creators of the annual, international "Open That Bottle Night" celebration of wine and friendship. The first bottle they shared was André Cold Duck. They have two daughters.

Banner by Piers Parlett