Editor's Note: Vardo in the Vineyard is a new series following Amy Tsaykel's life as she resides in an RV parked atop a vineyard in Sonoma County.

Sound the trumpets: I’ve decided to adopt a houseplant. On this seemingly trivial matter, I’ve hemmed and hawed. I’ve marched into the local nursery only to slink out again with icy cold feet. You’d think it was a puppy — or even an infant — that I was bringing home to my trailer; this will be my first houseplant in five years.

Brown thumbs are downright shameful for someone working in the wine business: I sample the fruit, help crush it into must, and peddle the wine. So why can’t I seem to grow the stuff?

Left: Welcome to my vardo. Ever noticed how you can't kill AstroTurf?

As I begin walking the vines this harvest season, sampling fruit for our winery and admiring the painstaking work of growers, this question echoes in my mind. In 2009, I bought an armload of succulents from a shelf labeled “disaster proof.” Within months, they drooped dead over my windowsill, lanky with overwatering. I haven’t had the heart to brutalize another living thing.

It wasn't always this way. Once upon a time, I taught at a rustic school in the Blue Ridge Mountains, where we regularly pulled our sustenance from the earth. I began my days by digging in black soil and finished by chopping vegetables to feed the entire student body.

Admittedly, I was always better at weeding — yes, killing the plants than growing them. Thus, in my recent adult life, I’ve intentionally been responsible for no one but myself. And I wish to keep my freedom while more firmly rooting down. But, for the first time in years, I have an urge to care for another living thing. I want to better learn the art of cultivation: but how?

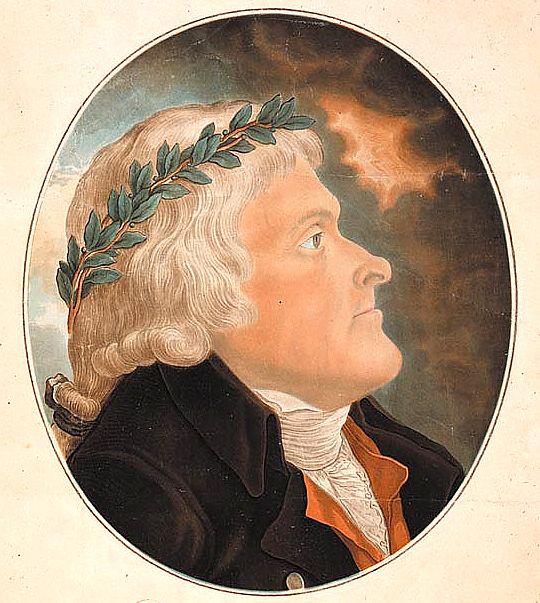

For guidance I turn to Founding Father, aspiring winegrower, and (yes!) fellow plant-killer Thomas Jefferson. After traveling Europe and collecting 23 varieties or "suitcase cuttings" of Vitis vinifera, Jefferson hoped to bring viticulture to the New World, starting in Monticello. Apparently the cuttings didn’t pack well with wigs and pantaloons, because they survived no better than my “disaster proof” succulents.

Right: Thomas Jefferson, although a tireless champion of farmers, apparently killed a few plants in his day. Who knew?

It was the work of later winegrowers, namely “father of Virginia wine” Gabriele Rausse, that eventually coaxed Jefferson’s vision to life. I recently caught up with Rausse, who put Jefferson’s efforts into perspective with a history lesson and a few tips for burgeoning growers.

Experiment. When Jefferson imagined winegrowing in the U.S., he was thinking outside the box. “Jefferson was interested in finding an agricultural crop that could disconnect the ‘new US’ from Great Britain” says Rausse. “When he went to France as ambassador, he started to look at what France needed, and at the possibility (what a dream!) of seriously growing grapes.”

We are each capable of taking risks. Isn’t the world bigger and better for it?

Expect the unexpected. Isn’t a little chaos normal? We’d be wise to forgive ourselves when things don’t go according to plan — and wiser to expect it.

"Filippo Mazzei had already been in Virginia (1773) and planted a vineyard at Colle (one mile from Monticello) and failed—not because of Phylloxera, but because the Revolution started. The vineyard was abandoned, and the horses of the mercenary Hessian troops decided to eat all the vines."

Horses ate the grapes, people. Horses! Who’d have guessed?

"There is actually a letter written by Anthony Giannini ( a man brought over by Mazzei) who was in charge Jefferson’s orchard and vineyard when Jefferson was in France. Giannini writes to Jefferson to say: 'I would be happy to make some wine for you but the grapes disappear year after year before they are ripe.'

"I think the reason of the failure is really that [in light of the Revolution] growing grapes and making wine was not so important."

You read that correctly: growing grapes and making wine is not always important. Keep it in perspective, suggests Rausse. If you are in the midst of a revolution, maybe (?) winegrowing should not be your top priority. And if you fail, move on.

Be persistent. Be willing to try and fail and try again: “Jefferson is recorded to have planted grapes 10 times. I always say that Jefferson didn’t fail. He just didn’t live long enough to finish his experiment.”

In his role as Director of Gardens and Grounds at Monticello, Rausse sees the fruits of his and Jefferson’s collective labors every day. “I love that Jefferson wasn’t working so much for himself but for everybody.” Process over product, says Rausse. Forget about any end result, and just nurture the life in front of you.

This a lot of heady advice for a woman who simply wants to grow a houseplant. Now all I need to do is choose my victim — er, plant.

Below: Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello. (Leonard Phillips)

In my last column, I referred to my life parked in a trailer at a small airport. Home is where I have space to explore and room to breathe — air. I need air. Is my ideal plant the same way?

Turns out, there is such a thing as an air plant. Tillandsia grows without soil. I can mount it in a glass case, terrarium-style, on the wall of my trailer. So I order one online and cross my fingers.

It’s an experiment. Anything could go wrong. And if I fail, I will try again.

Here’s to the elusive art of cultivation, and to those who succeed against the odds.

House Wine

Is there any such thing as disaster proof living? Frank Cornelisson, who planted his vineyard at the base of an active volcano, would likely argue not. His wines, MunJebel of Etna Rossa, are continually at risk. Aren’t we all—and isn’t that more reason to savor more deeply? According to independent winemaking consultant Bradley Friedman of Napa, the bottle of choice is MunJebel 7.

With great enthusiasm, I also recommend the lovingly crafted wines of Gabriele Rausse.

To keep up with Amy, be sure to follow her on Twitter and Instagram.