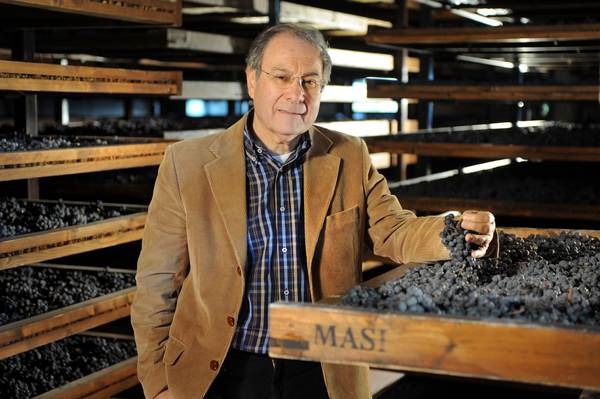

If your family’s company were named after the “small” valley in Italy that your ancestors purchased in the late 18th century, you’d be justified in not wanting to be the generation that dropped the ball, right? Well, Sandro Boscaini, the sixth generation to lead Masi Agricola in Vaio dei Masi in Valpolicella just north of Verona in the Veneto region of Italy, is in no danger of letting that happen. On his watch, Masi has become synonymous worldwide with Amarone, the powerful and intense red wine made from partially dried grapes. Masi makes five versions of Amarone that account for 20 percent of the total production in the Veneto. It’s that large.

Sandro has been a guardian of the region’s proud traditions. The Boscainis also manage the oldest estate in Valpolicella, which was once owned by the descendants of Dante, the 14th century poet. And Sandro has been a restless pursuer of innovations.

He is a man with a long view, typical, I guess, of someone whose heritage is steeped in so much history. Two of his children, the seventh generation, have signed on as well. Raffaele coordinates the Masi Technical Group and is director of marketing, and Alessandra is director of sales. Sandro’s brother Bruno is production and plant manager, and another brother, Mario, advises Masi but operates his own wine company.

If you’ve never tried an Amarone, think how a wine made from raisins might taste: concentrated, earthy, dry, warming, somewhat like Port. Some suggest you drink it toward the end of meals, calling it a meditative wine, and with hints of chocolate, spices, dried fruits and an attractive bitterness, I can certainly see that.

I’m writing about the 2008 Masi Riserva Costasera Amarone Classico now because the holidays are almost upon us and you might want to give this to the wine lover in your life. It’s pricey, all Amarones are, but for a good reason: the appassimento process, created by the Romans.

Here’s how it works: selected bunches of grapes are placed on bamboo mats during winter in drying lofts, usually places where cool winds can assist in the natural drying process while reducing the chances of mold developing. Because the Masi family marries tradition with innovation, its drying lofts are equipped with state-of-the-art humidity and temperature controls.

Amarone is made primarily from three local grape types, mostly Corvina and Rondinella and Molinara, the same grapes as the gulpable, drink-while-young Valpolicella. The Riserva also contains the ancient, late-harvested grape, Oseleta, that Masi rediscovered and resuscitated. Before the wine is vinified, the grapes dry for about 120 days and as they dry, they lose between 30 and 40 percent of their weight, in water. The process concentrates flavors, changing the flavor profile of the resulting wine.

Raffaele was in town recently and talked about that. “With the drying, the first effect is concentration, which of course is the concentration of the sugars, acids, tannins, everything gets richer,” he told me.

“Let’s say that a transformation of flavors happens,” he added. “We have this evolution, it’s extra ripening.”

With the higher concentration of sugar comes higher alcohol, between 15 and 16.5 percent, as the wine is fermented completely dry. This is a costly process not only because of the time that goes into it — a minimum three years in oak for the Riserva concentrates flavors even more — but it’s very risky. Only after the grape drying process and the juice is assessed do winemakers know if they can make an Amarone in a given year and some years they don’t. Also consider the increased number of grapes that go into a single bottle. Masi labels bear an authentication stamp that reads: “Appaxximento Masi Expertise, Sandro Boscaini,” with the xxi signifying the 21st century.

Raffaele says Amarone is made to be enjoyed young and to be easy-drinking but can easily age for more than three decades. Masi calls it “The Gentle Giant.” I’ve never thought of Amarone as easy or gentle. I enjoy them when they are mature but challenging, unfolding their secrets in small sips that demand reflection.

After it had been opened for quite a while, the Riserva, six years old and still very young, showed me why Masi believes that it “complements Barolo and Brunello as the aristocracy of the Italian wine world.” However, make no mistake. It is a modern version, sleek and elegant.

This mix of tradition and innovation is embodied in Raffaele, who speaks with pride of the work Masi is doing with university researchers to, among other things, find out why of the three main grapes only Corvina is affected by botrytis.

Raffaele manages a team of 12 specialists — people who oversee everything from the vineyards in the Classico zones, to the actual winemaking, and including the label designers. The group also explores modern winemaking techniques and ancient, indigenous grape varieties, operating vineyards that experiment with clones. “It has been always a question of updating the techniques to the state of the art,” Raffaele says. “It has been a question of exploring new roads, but all of them while looking at the past.”

Indeed. Raffaele enjoyed telling this story: ‘“One day when I was 11 or 12 and my parents were on vacation I stayed with my grandparents. I followed my grandfather, Guido, all day and one day he visited the vineyards to see if it was time to pick. So we walked among the vines and he just gently squeezed a bunch in his hands and said, ‘too hard, another week.’ It was like a mother kissing her child’s forehead to learn if he has a fever. Just like that. With no instruments.’”

In 1958, Guido noticed that the grapes he was getting from some vineyards were truly exceptional. And that’s how Masi came to make single-vineyard cru Amarone. Having had the 2007 Mazzano Amarone della Valpolicella Classico, I’m glad he did.

And of the next generation, Raffaele tells this story: “My daughter Matilda is 10 and she has a great palate. When she was seven, I was driving her to school with a friend whose dad had allowed them to taste a wine. Her friend said, ‘it was too strong.’ But Matilda said, ‘no, it was more intense.’’’

It sounds like things will be quite fine at Masi in the hands of the eighth generation.

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist, and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times, as well as at The Journal.