HISTORY

Viticulture in Austria dates back as far as 700 BC when the Celts were making wine for everyday consumption and special rituals. Over the following centuries winemaking saw plenty of ups and downs – it thrived under the Romans, suffered with the invasions of the Bavarians and Slavs, boomed in the 16th century, and was decimated by fungal diseases and phylloxera in the 1800s. Although it took a few decades for the industry to recover, it allowed for the replacement of lower quality grapes with superior varieties. Following World War I, Austria became the third largest wine producer in the world, with the majority of its product being exported in bulk for blending with wine from Germany and other countries.

The 1980s saw copious amounts of wines produced in Austria that were light and highly acidic and generally unappealing to the consumer. Wine brokers realized that with the addition of a small amount of the sweet-tasting diethylene glycol, a component commonly found in antifreeze, these wines could be made saleable. The scam eventually collapsed when German wine quality control scientists discovered the presence of the chemical in some of their low-end wines. This led to the realization that some German producers were illegally blending Austrian wines with theirs. Although the amounts of glycol present in the wine weren’t highly toxic and there were no fatalities, word spread and the scandal crushed Austria’s wine industry. Exports collapsed and many countries banned Austrian wine entirely.

As it turns out, the “antifreeze scandal” actually ended up being the salvation of the winemaking industry in Austria. The Austrian Wine Marketing Board was created in 1986 and Austria’s membership in the European Union sparked additional revisions to existing wine laws. Tough new guidelines and regulations were enforced, and the emphasis moved toward quality. Winemakers shifted gears as well and in order to accommodate consumer demand began producing dryer styles of white wine and increased red wine production. Today, in regards to production criteria, Austria is one of the top countries in the world with some of the highest standards.

GEOGRAPHY & CLIMATE

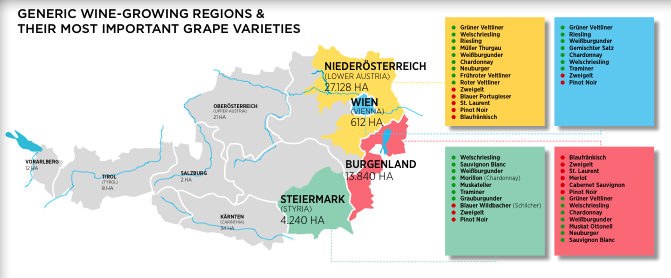

Austria is a landlocked country slightly smaller than the state of Maine and includes much of the mountainous territory of the eastern Alps and the Danube region. Winemaking in Austria is concentrated in the eastern portion of the country, in three major wine growing regions: Niederoesterreich (Lower Austria), Burgenland and Steiermark (Styria). In addition, Austria has 16 smaller wine regions, including Wien (Vienna) and the areas of Bergland. Austrian wines can be classified as DAC (Districtur Austriae Controllatus; Latin for Controlled District of Austria), which is the legal abbreviation for special region-typical quality wines.

The climate of Austria is similar to the climactic conditions found in Burgundy, France and is characterized by warm, sunny summers and long, mild autumn days with cool nights. Wine regions are influenced by Atlantic airstreams from the west, by the continental weather of the Hungarian Plain to the east, and by the Mediterranean to the south. These influences result in an early spring followed by a long growing season that is typically warm and dry. The Danube Riber and Lake Neusiedl also have a big effect on Austria’s wine growing regions. The river water reflects sunlight and protects the nearby wine areas from major changes in air temperature while the regions surrounding the lake are ideal for growing varieties used in prized dessert wines like Beerenauslesen and Trockenbeerenauslesen. As for rainfall, the eastern area of the country receives about 400 millimeters annually while in Styria rainfall levels can reach over 800 millimeters each year.

The majority of vineyards in Austria are located at an elevation of approximately 200 meters. An exception is Lower Austria, where wine growing extends to 400 meters. The highest altitude vineyards are found in Styria, at about 560 meters above sea level.

A wide range of soil types can be found within each grape growing area. In the Weinviertel and Danube Valley loess prevails, while primary rock is more typical in Krems, Langenlois and Wachau. In the Thermenregion, loam and limestone are the most common types of soil, while Vienna, Carnuntum, and Bugenland feature a diverse array of soil including slate, loam, marl, loess, and purse sand. In Styria, brown earth and volcanic soils predominate.

GRAPE VARIETIES

Austria has approximately 118,000 acres under vine maintained by about 32,000 wine producers. The assortment of microclimates and terroirs found within the country allows for the cultivation of numerous types of grapes. The national wine authority has officially authorized 35 varieties – 22 white and 13 red – for the production of quality wine. Over the last 20 years the proportion of red wines has doubled and now makes up almost a third of Austria’s vineyards.

Austria is perfectly suited for popular varieties like Riesling, Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Merlot, and Syrah, however its most prominent grape variety is Grüner Veltliner, which accounts for nearly one third of Austria’s vineyards. Other widely cultivated white varieties include Neuburger, Rotgipfler, Zierfandler and Roter Veltliner.

Grüner Veltliner: Indigenous Austrian variety, the wines have a fruity bouquet with a hint of spice, fresh and lively, herbaceous, green flavors of white pepper and green bean, very food-friendly.

Welschriesling: Austria’s second most planted white grape and not related to the true Riesling, delicate aroma with hints of apple, light wines of lesser structure, elegant acidity.

Weißburgunder: Also known as Pinot blanc, compact, with a nutty aroma, powerful and harmonious.

Riesling: Also called Rheinriesling, elegant, multifaceted fruit aromas, racy, delicate with classic fruit.

Neuburge: Well balanced, nutty aroma, soft structure with good body.

Chardonnay: Also known as Morillon or Feinburgunder, displays green apple fruit notes, fine acidity.

Sauvignon blanc: Also called Muskat-Sylvaner, elderberry bouquet and grassy spice, typical varietal character.

Blauer Zweigelt: Also known as Rotburger, Austria’s most planted red variety, lighter style red wine, similar to Grenache or Gamay, rarely oaked, fruit notes of black cherry and raspberry.

Blaufränkisch: Full-bodied and powerful with good acidity and tannin structure, complex fruit notes of tart cherry and blackberry, a velvety finish, age-worthy.

Blauer Portugieser: Fruity and mild, low in acid and alcohol content.

St. Laurent: Velvety dry with exceptional fruit, pleasant soft tannins.

WINE LABELS & CLASSIFICATIONS

Austrian wine law is based on European wine legislation with controlled origin, capped yields, quality designations and official quality controls as its primary elements. Three general quality designations are recognized: Tafelwein (table wine), Qualitätswein (wine of quality), and Prädikatswein (“certified” wine). The categories are determined by the sugar content of the grape must, displayed according to the Klosterneuburger Mostwaage (KMW) system. Important elements of the label are origin, varietal, vintage, quality designation, alcohol content, residual sugar, official control number, producer, and bottler.

Tafelwein: Essentially “table wine.” It has at least 10.6° KMW, and it is permitted to add sugar to the must.

Landwein: Translates to “land wine.” Usually served as the house wine. It is classed under the general category of Tafelwein, but is required to show its region of origin on the label. The minimum is 14° KMW. Sugar can be added.

Qualitätswein: Also called “quality wine." These wines have a minimum of 15° KMW, and the label must go one step further than Landwein and show its specific wine growing area. You can add sugar up to 19° KMW in white wines, and up to 20° KMW in red wines.

Kabinett: Falls under the broader category of Qualitätswein, but must have a minimum of 17° KMW, a maximum alcohol by volume of 13%, and a maximum residual sugar level of 9 g/l. You may not add sugar to the must.

Prädikatswein: This category includes Spätlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese, Eiswein, Schilfwein, Trockenbeerenauslese and Ausbruch, and each has their own minimum and maximum KMW levels.

Spätlese: Translates to “late harvest,” this classification has a minimum of 19° KMW, and the addition of grape must for sweetening is not permitted (as it is in Germany.) These wines may be sold after March 1, while the other Prädikatsweins cannot be sold until after May 1st.

Auslese: Means “selection” in German, and it’s used to describe the perfectly ripened grapes that are hand selected and pressed separately from the other grapes. A little bit sweet, but can still be enjoyed as a “drinking” wine. Minimum of 21° KMW.

Beerenauslese: Translates to “Selected berries.” The grapes are left to ripen longer than in any previous category, and have more residual sugar. Add to that the mold known as “noble rot," which causes the grapes to shrivel and concentrate further, and we move into dessert wines. The minimum KMW is 25°. Often abbreviated “BA.”

Eiswein: Also called Ice Wine, these wines are made from grapes left on the vine until the cold weather and frosts arrive. They must be picked at night to insure that the temperature remains below freezing until the grapes are harvested and pressed. The water left in the grape remains frozen, so only the most concentrated of flavors comes out. It has a minimum 25° KMW.

Schilfwein: Also called Strohwein, it is a method of making dessert wines. The grapes are harvested late and later air dried on straw mats for at least three months to concentrate their flavor. Minimum of 25° KMW.

Ausbruch: This refers to a technique of making dessert wine using grapes affected by noble rot. The production method originally came from Hungary where it is used for making Tokaji.

Trockenbeerenauslese: Translates to “dry selected berries” and called TBA for short, this classification represents the sweetest wines. The grapes are left on the vine until they are virtually dried out and have gone through a big bout of noble rot. This makes them highly concentrated. The minimum level is 30° KMW.