O thou invisible spirit of wine! If thou hast no name to be known by, let us call thee devil!

Othello: Act 2, Scene 3

When people think of England, usually images of Shakespeare, rock and roll, bad weather and even worse food come to mind. Now England is making a push to be known for sparkling wine and we have climate change to thank for that.

According to British Environment Secretary Elizabeth Truss, the "industry is fizzing." British government data shows "total acres of vineyards now stands at more than 4,500, up from 1,879 in 2004, with 470 vineyards now open for business." The south of England is blessed with soils very similar to its neighbor, Champagne (only 88 miles separate the regions). However, traditionally the weather in England has been too cold for grapes to consistently ripen. Sparkling wine is made with grapes that are not fully ripened - and with global warming giving the industry a helping hand, Southern England is now making very good sparkling wine.

The University of East Anglia (UEA) in England recently came out with a scientific paper evaluating England's suitability as a winemaking region. Among the conclusions are that conditions in England are conducive to growing cool climate varietals but that there will be a lot of variation from vintage to vintage related to weather. UEA's lead researcher, Alistair Nesbitt, acknowledged the influence of climate change, “The UK has been warming faster than the global average since 1960 and eight of the warmest years in the last century have occurred since 2002. Producers recognised the contribution of climate change to the sector's recent growth, but also expressed concerns about threats posed by changing conditions."

Climate change, according to Nesbitt, is making England more like Champagne. He notes that the temperature in Southern England during the growing season over the last 10 years has been above 55 degrees Fahrenheit and that this "is around the same temperature as the sparkling wine producing region in Champagne during the 1960s, 70s and 80s."

The key factor in vintage variation, according to Nesbitt, is the amount of June rainfall which can vary greatly. We spoke to Emma Rice, winemaker at the well respected English sparkling wine producer Hattingley Valley, who confirmed the challenge of making wine in rainy England. Rice noted that excessive rain and low temperatures can cause the berries to fail to ripen which can have a serious impact on harvest yield. "2012 we produced 11 tons to 2013 off the same vineyard area producing 211 tons," Rice noted.

A man cannot make him laugh – but that’s no marvel; he drinks no wine.

Henry IV Part II: Act 2, Scene 4

Up until recently, English sparkling wine estate ownership has been mostly the purview of wealthy enthusiasts, though this is beginning to change. French Champagne house Taittinger has recently invested in a property in Kent in Southern England. The new estate called Domaine Evremond will start planting in 2017. It is a joint venture between Taittinger and its UK distributor Hatch Mansfield. Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger spoke to the U.K.'s Telegraph about the joint venture: "We now have many very good English sparkling wines. Global warming helps as the climate is more generous. But when things are good we don’t talk about nationality. Mozart is Mozart. Alec Guinness is Alec Guinness. Brigitte Bardot is Brigitte Bardot." Other French influences include Hambledon in Hampshire run by Hervé Jestin, formerly of Champagne Duval Leroy and Exton Park made by Frenchwoman Corinne Seely.

Emma Rice talking with Grape Collective at one of Hattingley Valley's vineyards in Hampshire

In an October 2014 interview, Dorothy Gaiter of Grape Collective spoke to Christian Seely, the managing director of AXA Millésimes, the wine division of the French company AXA which owns top vineyards around the world including Château Pichon-Longueville, Chateau Suduiraut and Quinta do Noval among others.Seely is co-owner of Coates and Seely, a Hampshire winery which launched in 2007 and now produces up to 55,000 bottles of wine. "There are places in Southern England which have a geology which is almost identical to that which exists in Grand Cru Champagne vineyard sites, so chalky soils with a bit of clay mixed in. The vineyard that we planted in a little valley in Hampshire, it has a geological profile which is exactly a Champagne profile. I planted Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier and we built a little winery with a lot of help from consultants from Champagne. We've been making English sparkling wine since 2009 actually." Seely spoke of competing with Champagne in blind tastings and coming in the middle of the pack. And "if you come somewhere in the middle of the tasting of various Champagnes and you've only just started a few years ago in England, then you're doing pretty well."

England now has a wine store in South London, the Wine Pantry, which is solely dedicated to English wines. Yet finding the wines outside of England can still be a challenge. Only Ridgeview Estates is easily available in New York. Dorothy Gaiter interviewed Ridgeview owner Tamara Roberts and compared the wines to Champagne. Gaiter was impressed with the quality of the Ridgeview; "These Ridgeviews all ranged from $40 to $45 and compared to the wines produced in this price range by some of the large Champagne houses—not the authentic, small, grower-Champagne makers--I’d have to give the nod to the Ridgeviews."

In addition to finding the right places to make wine, England now has a professional winemaking program, Plumpton College in East Sussex, that is training the new generation of English winemakers and viticulturists.

We talked to Emma Rice, head winemaker at at Hattingley Valley and a graduate of Plumpton College's winemaking program, about the challenges and opportunities for English sparkling wine. Read the full interview here.

Christopher Barnes: Emma, Hattingley Valley, how long has the estate been here?

Emma Rice: We planted in 2008. First vintage in 2010.

Emma, how did Simon Robinson decide to become a winemaker and a vine grower?

Well, he had the farm existing already and decided that he would like to diversify what was going on in the farm and grapes were a bit of a passion of his ... well, wine was a bit of a passion of his. And he decided that maybe he could look into planting a vineyard. Did that in 2008 and we made our first wine in 2010 and here we are.

How long does it take before the grapes reach the stage where they're good wine grapes?

We can take a small crop in the third growing season. But to be honest, they are not really producing a fully mature crop until the fifth or sixth growing seasons. Then they will mature for another 10 to 15 years, tail off at about 25 years old.

What is it about Hampshire and the climate here that allows you to produce good sparkling wine?

We're on solid chalk, so it's very similar to the Champagne region of northern France and we have a very, very long, cool growing season. We don't get huge sugar ripeness. We get good acidity, we maintain the acidity at a very nice level. But we get very good flavor development in the grapes because they have such long time to get to the sugar ripeness that they do.

How did you get involved with winemaking?

I was in the wine trade in London for eight years and I read about Plumpton College in East Sussex offering winemaking courses. I signed up and then that was it. I set on my path to winemaking.

How did you end up in Hattingley Valley?

I went from East Sussex to Napa Valley, California, Tasmania, Australia; back to Sussex and that's when I met Simon. I set up a laboratory in Sussex testing wines and grapes. I met Simon through doing that and then I became involved in helping him to build the winery here in 2009.

I bet the climate is a little different in Napa and Tasmania than it is in Hampshire, England.

Surprisingly, Tasmania is probably much closer to the English climate than the Napa climate but Napa was an exceptionally dry climate by comparison to here in England.

You get a little bit more rain here.

Just a little bit.

And gray skies.

And gray skies. Not so much guaranteed sunshine and we get the rain throughout the growing seasons. Whereas, in Napa they get the rain in the winter, no rain at all during the summer. They irrigate control it nicely. We don't have to irrigate. We are managing too much water. Whereas in Napa I believe they are managing not enough. It is two extremes.

Tell us about the process of making sparkling wine here.

Tell us about the process of making sparkling wine here.

We get the grapes in, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, handpicked just as they do with Champagne. We bring them into the winery, a whole bunch pressed in Champagne presses. These are bladder presses and horizontal tilt plate presses which are designed in Champagne for use with Champagne grapes. We whole bunch press and we take I think between 50 to 60% yield from the grapes. So, a four ton load we will take between 2,000 and two and a half thousand liters of juice, depending on the quality of the grapes.

Then we ferment them as ordinary white wines, both the black grapes and the white grapes. And then this stage of the year, January, February, we are blending and making up what becomes the final wine...what will become the final wine. So we're blending not only the different varieties together, so our classic cuvee is 50% Chardonnay, 30% Pinot Noir, 20% Pinot Meunier, give or take depending on the vintage. We are making those blends up from a palate of maybe 60 to 70 different tanks. That takes a lot of time and effort and that's where we like to think the skill comes in, the real skill comes in.

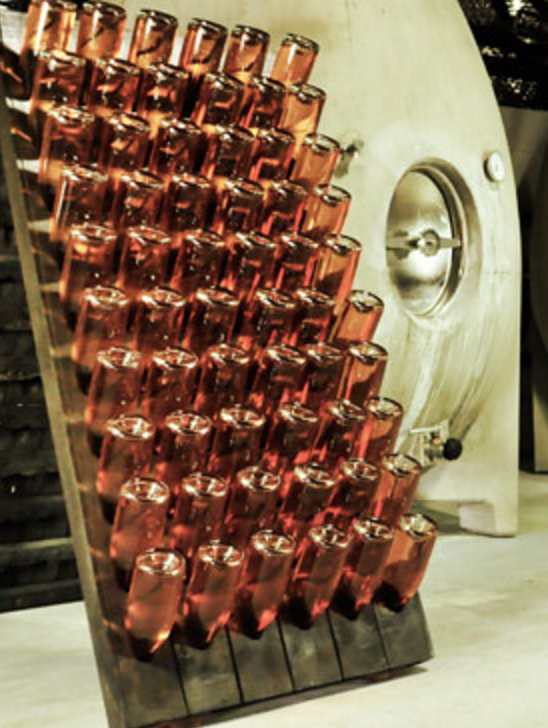

Then we cold stabilize and filter those wines, those final blends; ready to be bottled. We are doing a bottling run in March at which point we add sugar and yeast and riddling agents to allow us to do this process later here. Wine takes two or three months to ferment in the bottle, we end up with six bar of pressure, an extra 1.5% alcohol and therefore you have a fizzy wine, with lots of yeast in it so you can't see it in this bottle because it is such a small plug of yeast. We have to get that yeast out, keep the wine and the bubbles in and that is the disgorging process. At which point we take the yeast out. We add a small amount of sugary wine solution called the dosage at a level we have established by doing trials. That is what these are here for, for trials. Most of this process, this riddling process is not done by hand like this as they used to do in Champagne. It is done on the big machines that you can see behind you over there.

How did you decide on the blend with the three grapes? Was it to do with how the grapes grow here or was it to do with a taste profile that you're interested in?

We are trying with our classic cuvee, which is the traditional blend of the three varieties. We are trying to come to a Hattingley Valley house style. It's very difficult and Champagne, it takes them decades and generations of winemakers to get to that point. We are in our very early days, we are only in our sixth vintage. We've had some very variable crops over the last five to six years where sometimes the Chardonnay does really well, sometimes the Pinot does very well. And sometimes we get the perfect storm and they both do well and you have the maximum choice.

We are working towards what we think is going to be the Hattingley style. Which so far, is now starting to look like 50% Chardonnay, 30% Pinot Noir, and 20% Pinot Meunier. It has not always been like that. One of the other crucial factors that we use is oak barrels. We do a lot of fermentation of the base wine in old Burgundy barrels. That really is helping us to produce this signature style and we're now able to start keeping reserve wines back. So we keep 30% of the crop back in tank for the next year so that we can produce this true, non-vintage style as they do in Champagne, all be it on a slightly smaller scale because we don't have the luxury of the tank space but it also helps us to even out the crop differences year to year as well.

Emma, the English sparkling wine industry. When people think of England, they don't think of wine. They think of fish and chips, they think of bad weather, wine is usually not one of the things that comes up. Yet it has been getting a lot of press recently. There have been these blind tastings where they have been going head to head with Champagne and doing very well. What's going on with the English wine industry?

I think there's been an influx of people doing it properly. It no longer is it the domain of hobbyists and amateurs who are planting a few grapes in their back garden. It's people who are doing it on a serious scale with good professional advice and knowledge and the right equipment. It is also the realization that we need some place for our strengths. We are very good at growing under ripe grapes in England. What you need for good quality sparkling wine is under ripe grapes. We're not trying to grow Chardonnay to make a Burgundian style Meursault or Chassagne-Montrachet. We're growing Chardonnay, we have no intention of getting it to full ripeness, we couldn't. Occasionally we probably could but, we are playing to our strengths and we found what we're good at and that's I think becoming very apparent in the results we're seeing.

How does England or Southern England ... is it really Southern England that we're talking about?

Predominantly. Southeast through to the southwest. There are small pockets north of London in East Anglia where the micro climates are really quite good. There are other little spots further north as well, which are even more marginal. Some people are making good wine there, whether they will make great wine is debatable. They are taking a huge risk. The further north you go the greater the risk there is.

What is the risk? Frost?

Everything. There's the frost in the spring and the autumn. There's the lack of sunshine, lack of warmth and too much rain. There's every disease going. Every fungal disease you can think of for a grapevine. We get it here. Everything is against us.

How does Southern England compare with Champagne in terms of climate?

We have cooler climate. They have a much more continental climate. They don't have the maritime influence that we have all over England; being an island. They have hotter summers and a hotter growing season. Probably colder winters as well, not so important. We get a longer, cooler growing season than they do. Sometimes that works against us, sometimes that works in our favor. 2003 would be a good example where England probably produced better grapes for making quality sparkling wine than the majority of Champagne. It was such a hot year.

What about the soils? How do the soils compare?

We have the same chalk, which runs through the south downs, the South and the North Downs in the southern part of England, coming out as the white cliffs of Dover going over through Northern France and coming up again in Champagne. Same chalk, same seam of chalk. We have different topsoils. We have a bit of clay, bit of green sand, other more loamy topsoil but the soils themselves are essentially the same. It's just we are generally wetter and cooler than they are.

How do the wines compare?

We have slightly higher acidity I'd say. Lower PH, slightly higher acidity. In terms of flavor profile, it can be very similar, very, very similar. The markers for English sparkling wine are high acid, particularly green apple-y kind of acid. Then hedgerow floral flavors; elderflower and other white flowers as hedgerow flavors, which you don't get in Champagne. It depends on the style and how long it has been lees aged for, but some people might say that English sparkling wine now tastes like Champagne did 20 years ago.

----

More on English wine:

Dorothy Gaiter's interview with Christian Seely of Coates and Seely

Dorothy Gaiter's interview with Ridgeview Estates owner Tamara Roberts

Read Jancis Robinson on English wine

Watch Monty Waldin's introduction to English wine