Sherry isn’t for “blue-haired grannies” anymore. You've surely heard this proclamation made by journalists (like me) as we help to usher in a new era for these great fortified wines made in and around Jerez, Spain. Don’t ask me why, but the “blue-haired granny” has become the most popular trope for describing thist most recent surge of interest in the category. For the record, my grandmother, along with most of her peers, drank virtually nothing but schnapps, vodka, and Manischevitz (on holidays), so I’m inclined to wonder whether this apocryphal sherry-drinking grandma ever really existed. My hunch is that, if she did, she was certainly British, and probably kicked the bucket at some point during the Falklands Crisis. But while the drinking habits of the grandmothers of American wine writers remain subject to debate, it can’t be denied that sherry has lately become improbably hip.

Within the last two years alone, two sherry-focused books have appeared on shelves, both of which have become required reading on the subject. In 2012, the encyclopedic Sherry, Manzanilla and Montilla made its way into bookstores, courtesy of Peter Liem and Jesús Barquín, which was followed just this fall by Talia Baiocchi’s more user-friendly, narrative-driven Sherry: A Modern Guide to the World’s Best-Kept Secret. There is even the annual Sherry Fest, a big, well-organized, bicoastal promotional campaign dedicated to preaching the sherry gospel to stateside consumers through a wide range of seminars, dinners, and tastings. For a category that once verged upon utter neglect, sherry’s fortunes have certainly changed.

Thanks to this long overdue evangelism from the trade, a new and ever-more-curious generation of drinkers has finally begun to develop a sense of context for these wines, which have always played such a defining role in the culture of their native Andalusia. Although this attention has been long overdue for the category as a whole, one of the most compelling developments of the nascent sherry renaissance has been the emergence of a new style known as en rama, which roughly translates to “on the branch” or “raw.”

When we talk about the en rama trend, we’re referring specifically to the so-called “biologically aged” categories of fino and manzanilla sherry. Unlike the nuttier, richer “oxidatively aged” styles like oloroso, which intentionally come into contact with oxygen during the aging process, fino and manzanilla sherries are fortified only to around 15% alcohol, which allows a layer of living yeast, known as flor, to develop on the surface of the wines as they mature in barrel (hence the term “biological aging). In addition to imparting tell-tale briny and saline aromas and flavors, with a characteristic biscuit-y yeastiness, this protective film also protects the wine from being exposed to air. The result is the palest, freshest, and driest style of sherry, traditionally served with all manner of local seafood.

When we talk about the en rama trend, we’re referring specifically to the so-called “biologically aged” categories of fino and manzanilla sherry. Unlike the nuttier, richer “oxidatively aged” styles like oloroso, which intentionally come into contact with oxygen during the aging process, fino and manzanilla sherries are fortified only to around 15% alcohol, which allows a layer of living yeast, known as flor, to develop on the surface of the wines as they mature in barrel (hence the term “biological aging). In addition to imparting tell-tale briny and saline aromas and flavors, with a characteristic biscuit-y yeastiness, this protective film also protects the wine from being exposed to air. The result is the palest, freshest, and driest style of sherry, traditionally served with all manner of local seafood.

It may come as a surprise, but the production of these “biologically-aged” finos and manzanillas typically involves heavy fining and filtration before bottling in order to remove the bits of flor and other sediment that have developed during the course of the wine’s production. However, as Liem and Barquin mention in their book, this process unfortunately often “strips the wine of its color as well as its flavors and aromas.” As a result, this sacrifices some of the sherry’s natural richness and complexity for the sake of a more stable commercial product.

This isn’t to say that filtered sherries can’t be phenomenal, or that they’re inherently deficient in some way. To the contrary, many of them represent magnificent examples of their kind, numbering among the world’s most distinct expressions of vinous identity.

For better or worse, however, it can’t be denied that filtration does alter the nature of the wine. To that end, the en rama approach showcases a different, more raw (or primary) expression of sherry’s potential. Bottled with minimal filtration and released seasonally, en rama sherry offers a much closer approximation of what the wine would have tasted like in its natural state, taken directly from the cask, with all it aromatic intensity, fullness of body, and essential flavors intact. As great as this sounds, it’s worth noting that one style isn’t necessarily better than the other. Sometimes, all you want is a crisp filtered fino to wash down a plate of oysters on a hot summer day. The two approaches simply result in different but equally valid interpretations of the category, which, taken together, expand the region’s stylistic diversity and broaden the possibilities of what sherry can be.

Up until recently (with a few exceptions), the only viable way to taste sherry en rama was to go to Jerez, visit the bodegas, and taste the wine poured directly from the cask. In terms of commercial production, however, the phenomenon represents something rather new. As Sherry Fest co-founder Rosemary Gray explains, “For a long time, producers were apprehensive to release en rama sherries because they thought the wines were unstable. It wasn’t until there was enough demand that they started doing it more regularly.”

Since then, the style has quickly been embraced by sommeliers and other industry tastemakers, and impact is starting to be felt on the consumer side as well. As a response to this growing interest, the number of producers making enrama bottlings and exporting them to the United States and abroad has multiplied exponentially. A thrilling spectrum of en rama wines can now be found stateside, from bodegas both large and small, including such legendary names as Lustau, Gonzalez Byass, Valdespino, Barbadillo, Hidalgo, and Fernando de Castilla, among many others.

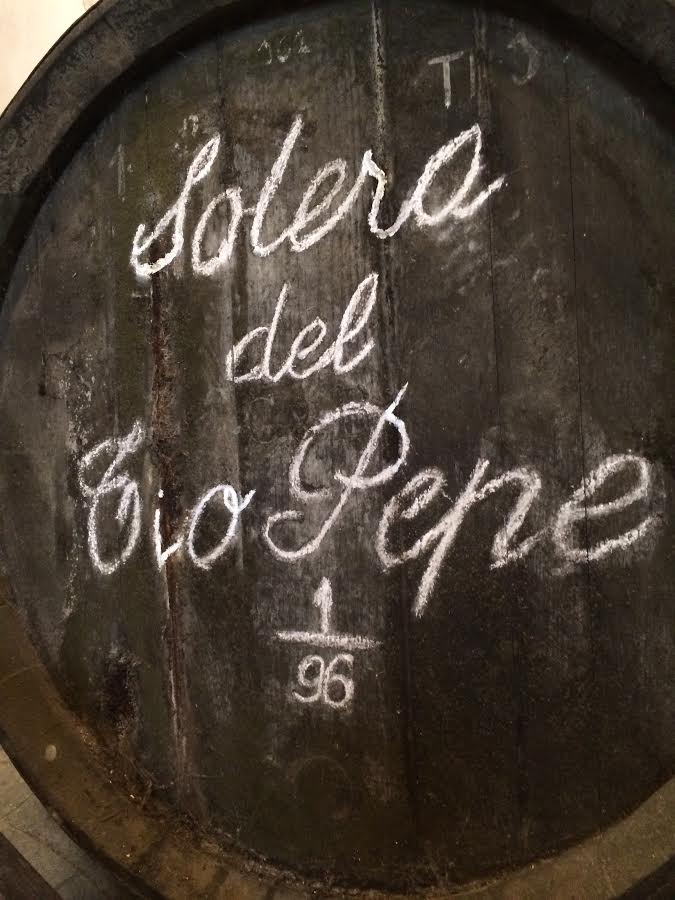

“It has almost become a sub-genre of sherry,” explains Andrew Sinclair, East Coast Sales Manager of famed producer Gonzalez Byass, which was among the first to bring an en rama bottling to market — in their case, a minimally-filtered version of their iconic Tío Pepe fino. “The phenomenon is highly emblematic of a new wave of consumers who are discovering sherry, but who aren't necessarily sherry drinkers; they're people who will include an en rama in their repertoire among things like German Riesling or Jura wines.”

“It has almost become a sub-genre of sherry,” explains Andrew Sinclair, East Coast Sales Manager of famed producer Gonzalez Byass, which was among the first to bring an en rama bottling to market — in their case, a minimally-filtered version of their iconic Tío Pepe fino. “The phenomenon is highly emblematic of a new wave of consumers who are discovering sherry, but who aren't necessarily sherry drinkers; they're people who will include an en rama in their repertoire among things like German Riesling or Jura wines.”

It’s no coincidence, then, that the rise of the en rama trend coincides with a general shift in the wine culture towards a greater openness to exploration. Part of this also involves the cultural embrace of a more hands-off or non-interventionist approach to winemaking. As Gray explains, “The en rama movement is popular now because it aligns with current wine speak. We are becoming interested in wines that are natural and un-manipulated versions of themselves. Also, since the releases coincide with the seasons, it gives a kind of vintage stamp to sherry. We have a contemporary wine culture that is interested in these values, and it’s easy to get into en rama when you’re already thinking of wine in these ways.”

To that end, just consider the way so-called natural wine has recently transformed from a fringe movement into one of the most talked about and central issues in the debate about wine. Additionally, similar developments in Champagne, for instance — another one of the world’s great blended, non-vintage wines — offer compelling parallels to the situation with sherry. The rise of “extra brut” or “zero-dosage” Champagne, which are bottled without any added sugar, point to a kindred desire to allow the wine’s underlying character shine through without additions or subtractions of any kind.

For those interested in understanding the essence of en rama firsthand, an ideal introduction to the style would involve drinking the limited-release Gonzalez Byass Tio Pepe fino en rama, which is sourced from a specific set of soleras (or system of casks), alongside the widely available filtered version of the wine. The difference in the size of production between the two wines is astonishing: approximately 22,000 barrels go into the solera for the regular filtered version as opposed just 443 barrels for the special en rama bottling.

On the basis of color alone, the distinction becomes immediately apparent: while the regular filtered Tío Pepe assumes a familiar pale transparent hue, the unfiltered version boasts an almost golden tone, hinting at the textural depth that awaits. On the palate, the classic version comes across as perfectly bright and crisp, still retaining a nice tang of flor. The results are all the more impressive given its production levels and worldwide distribution, but sherry is oddly one of those regions where quality and quantity aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. There’s no doubt, however, that the rarer en rama version offers the more complex drinking experience: it’s pungent and saline, with notes of yellow apple, green olives, and a hint of almond, along with a corresponding fullness of body that somehow manages to be bracingly acid-driven and fresh.

Perhaps Sinclair describes it best: “The en rama is like turbo-charged Tío Pepe. It's like taking everything in the Tío Pepe and concentrating it.”

Concentrating it? Or is it just a matter of letting the wine be what it already is?