Sometimes life can be viewed as a series of tests, challenges, hurdles. If they can be negotiated successfully, they make you stronger, your life sweeter. Think of all of the popular words of wisdom that embrace that notion. From the secular, “What doesn’t break you makes you stronger,” to the reverential, “God doesn’t give you more than you can handle.”

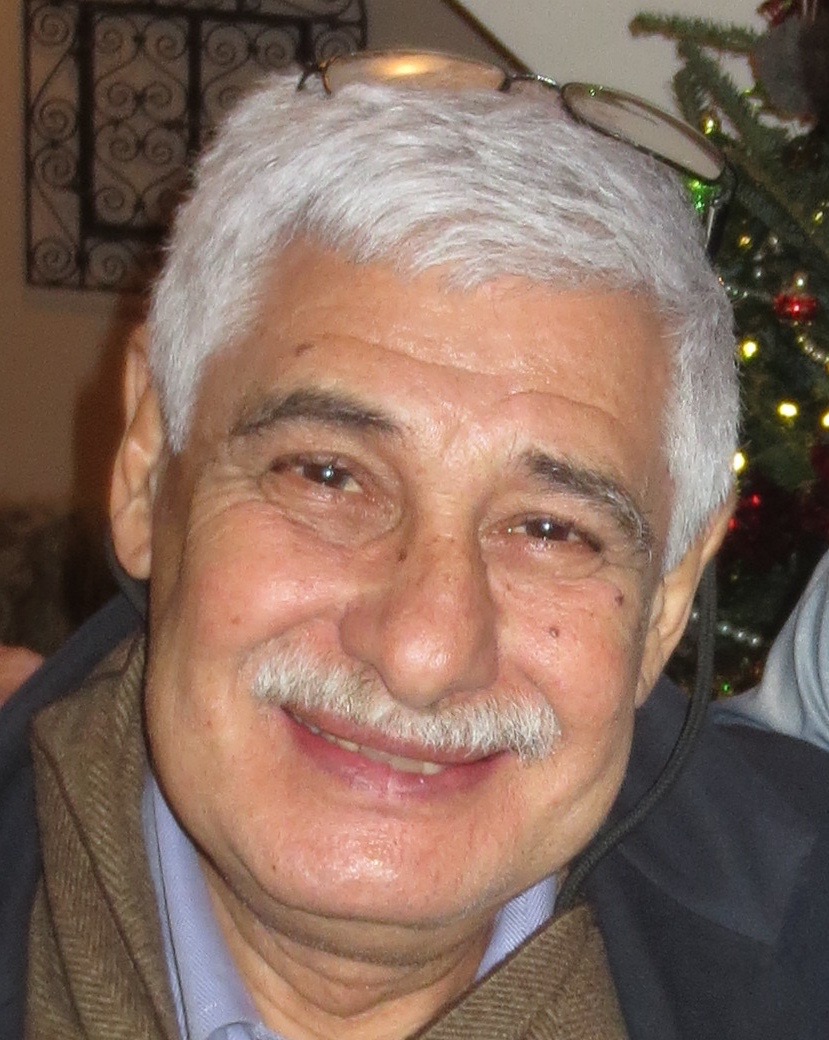

Jacques Capsouto, one of the three brothers who founded Capsouto Frères restaurant in New York City, which closed after 33 years following Hurricane Sandy, is almost Job-like in the travails he has endured over the past few years.

However, if there is such a thing as cosmic justice and my palate isn’t deceiving me, his new venture, Jacques Capsouto Vignobles, Mediterranean Blends, a line of Kosher wines he’s making in Israel, will be a big success. He’s been working on this project, with a consulting French winemaker, for 10 years. The first two wines from Capsouto’s line, which he’s dubbed Côtes de Galilée Villages, were introduced in the U.S. a few weeks ago. A white and a rosé (both $20 and from 2014), they are named Cuvée Eva, after his mother. Over lunch of Salade Niçoise and branzino at Rotisserie Georgette, just before he returned to Israel for his second harvest, they were mouth-watering delights. The white is 60% Grenache Blanc and had a fleshiness like white peaches and a fetching foundation of minerals. The pale rosé is mostly Cinsault and had good acidity, some earth and a hint of watermelon juiciness. If you served them to friends, you’d need a lot of bottles.

“I think that for a first vintage I did a very good job,” he told me after studying my face hard as I took my first tastes. I agree, but find his assessment modest. “The rosé is light and pleasant. I wanted a very light color and not too much alcohol,” he continued. “The white is complex and should be taken with a meal.”

Why Israel? I asked.

“California is saturated. I like Oregon but I don’t know Oregon,” he explained. “From 1957 to 1961, we lived in France after leaving Egypt, but it’s difficult to do business in France if you’re not French. The Israeli wine industry is young. This is an opportunity for me to do something good and good for Israel, too.” He told me that “between 50 and 55 percent” of his Sephardic Jewish family lives in Israel now.

“In Israel most of the wine is made like in California. The Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc. I’m producing something different, Mediterranean blends,” he said. His blends come from nine varieties: Carignan, Cinsault, Grenache, Mourvèdre and Syrah for the reds and Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Marsanne and Roussanne for the whites. The cuttings for his rented 55 acres came from France and the vines were certified by UC-Davis as healthy and authentic. Capsouto’s other wines will be available in a few months. They include Cuvée Samuel, an entry-level red named after his grandfather and younger brother; a reserve white wine called Cuvée Albert after his youngest brother, who died in 2010, and Cuvée Marco, a high-end red named after his father.

We met Jacques back in 1981. We were pretty new to New York and in October 1980, he and his brothers had opened Capsouto Frères, a charming, classic French restaurant in Tribeca. Their mother sat near the door, a welcoming presence. She and her husband were born in Turkey and Jacques and his brothers were born in Egypt. From there, the family emigrated to Lyon, France, to live among relatives while diving into its rich culinary culture. They emigrated to the U.S. when Jacques was a teenager.

Now, 1980 was way before Tribeca was cool. The frères were pioneers, and their French classics, especially their sweet and savory soufflés, made the restaurant and Tribeca high-end dining destinations in the city. Over the years, as we moved farther and farther north, we went to the restaurant less, but it was always among our top recommendations when friends were looking for a romantic place to eat. Jacques, now 70, supervised the kitchen and taught himself about wine. Samuel handled the business end, including the bar. (After Samuel married and had less time for the business, Jacques began ordering the wines and spirits.) Albert took care of the dining room.

It was a true family affair, and their definition of family extended to their community. Every Passover, they prepared a Seder from their grandmother’s recipes and donated the money they made to a charity in Turkey, their response to the deadly1986 attack on the Neve Shalom synagogue in Istanbul. Albert served on the neighborhood’s community board for 20 years, until he died.

When the terrorist attacks happened on 9-11, the brothers sheparded into the restaurant students from a school north of them, running “in the huge cloud of the World Trade Center,” a community board member told a neighborhood newspaper. They fed early responders free hot meals for more than two weeks and Albert went to Washington to petition the government for emergency aid to help businesses struggling in the aftermath. In 2003, their mother died. And in 2010, Albert, the baby, died from a brain tumor diagnosed only two months earlier. He was 53. The city’s Parks Department named a small, triangle park at Varick, Laight and Canal streets after him, a testament to his involvement in the community.

Hurricane Sandy, in 2012, dealt the two brothers a blow from which they couldn’t recover. The storm killed 117 in the U.S., among them 53 in New York State and 34 in New Jersey and cost billions in destroyed and damaged properties. The storm dumped more than five feet of water into the restaurant and the building across the street where Jacques lived and severely damaged his weekend house on Fire Island. They had no flood insurance and went into debt restoring the restaurant, on top of debt from restoring the restaurant after 9-11. Capsouto Frères never reopened after Sandy. China Blue, an upscale Chinese restaurant, now rents the space. Samuel and his wife and three adult offspring still live in New York City.

The upheaval caused by Sandy inspired Jacques to move more seriously on a project he’d started in 2004. That year, he had attended the wedding in Israel of a famous Israeli actress, who is a distant relative, and become enamored of the country’s wines. While there he visited wineries, talking to winemakers. At one point, Capsouto Frères’ wine list featured about 20 Kosher wines. When Yarden, the huge Golan Heights wine producer, introduced its wines in the U.S. decades ago, “Capsouto Frères hosted Yarden’s first tasting,” Capsouto told me.

He also got a taste of the Israeli government’s red tape. He told me that because so little land is in private hands and so much of it is owned by the government, he had to lease land from a commune. So he signed a 25-year lease in the Western Galilee, not the “it” areas, the Golan Heights and Upper Galilee. His vineyard was planted in chalk, limestone and clay soils with the aid of an agronomist, and his enterprise was certified Kosher by a rabbi.

Observing religious laws and practices, there’s no work on Friday and Saturday. “Friday, we could work a half day but that’s not long enough to do anything,” he told me. Every seventh year, the land must lay fallow, not cultivated by Jews, he explained. His goal is 28,000 bottles, 60% of which would be sold in the U.S. and the rest in Israel. Already, the Cuvée Eva wines have found spots on some of New York City’s more interesting restaurant wine lists.

The land he rents is near the village of Peki’in in Galilee, the site of one of the oldest synagogues still standing in Israel, he said. He told The Jewish Week publication, “I decided against the Golan Heights because it’s controversial. I searched for places along the Lebanese border where I am surrounded by four different religions -- Muslims, Jews, Christians and Druze. Like we started Tribeca [by opening the restaurant there in the early 1980s] I am starting something different in Israel.”

Mazel tov, Jacques Capsouto.

L’Chayim!

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.