Over the past decade, the wine world has been remapped. Many northern territories — England, Denmark, Nova Scotia, the Netherlands, Vermont, Maine and Michigan — now merit inclusion in any atlas of vines. They are among the cool climate areas once dismissed as unthinkable sources for the successful production of high-quality hybrid and vinifera wines that are now just that.

We can thank climate change for some of this, of course. But it’s also the confluence of vastly improved winemaker education and technology, a new generation of consumers who are more open and eager to explore what was once the wine “fringe,” and a wider appreciation of the brighter, fresher wines that cool climates arguably do best.

Michigan is no newcomer to wine production. But like many New World cool climate areas, its vinous history is based on native varieties, with vinifera being a far more recent innovation. Michigan traces its winemaking roots to 1679, when French explorers — faute de mieux — vinified native grapes growing wild on the banks of the Detroit River. Over the next two centuries, vineyard plantings expanded widely and, by 1900, Michigan had become one of the leading wine-producing states in the country. Then, as in every state in the union, Prohibition flattened the industry. By the 1960s, the number of commercial wineries in the state was just two.

Michigan vineyards were historically dominated by the hardy, prolific Concord, a versatile juice and table grape. But in 1965, the first French-American hybrids were planted on the eastern shores of Lake Michigan, in the state’s far north. These were soon followed by experiments with vinifera varieties, chiefly Chardonnay and Riesling. Soon after, Michigan State University began work to identify cold-resistant varieties that would make palatable, salable wines for the state's growers.

In the 1970s, Chateau Grand Traverse opened its doors as the first Michigan winery with the amibition to make European varietal wines, concentrating on Riesling. Their success encouraged others and today there are 139 wineries operating in Michigan. Most are small scale and vinifera based.

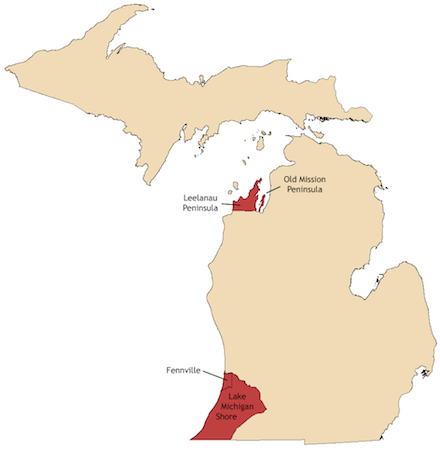

The state has four established American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) and the most notable wineries are situated in what is called the Traverse Wine Coast area, encompassing the Leelanau and Old Mission Peninsulas AVAs.  Here long, harsh winters and relatively high latitude are tempered by protective lake effects, extending the grape-growing season well into fall. This makes the region ideal for late-ripening varieties like Riesling and the many wine styles it is capable of giving. Cabernet Franc and Merlot, as well as Gewürztraminer, Pinot Blanc, Viognier, and Sauvignon Blanc also do exceptionally well in the region’s climate and diverse, glacially distributed soils.

Here long, harsh winters and relatively high latitude are tempered by protective lake effects, extending the grape-growing season well into fall. This makes the region ideal for late-ripening varieties like Riesling and the many wine styles it is capable of giving. Cabernet Franc and Merlot, as well as Gewürztraminer, Pinot Blanc, Viognier, and Sauvignon Blanc also do exceptionally well in the region’s climate and diverse, glacially distributed soils.

(Pictured, right: Map of Michigan AVAs)

When wine-loving friends who spend their summers in the heart of the Traverse Wine Coast area first told me some of their favorite bottles were Michigan whites, I arched an eyebrow. Surely local loyalty and “vacation bias” (whatever we drink on holiday tastes best) were coloring their view. But my skepticism was quickly overturned. They introduced me first to the wines of L. Mawby, an established sparkling house in Leelanau, whose head-turning NV Talismon blends traditional Champagne varieties with a sprinkling of other white grapes to yield a wine of gorgeous refinement and complexity.

I went on to explore some of the fine, tensile Rieslings of Black Star Farms, the juicy crowdpleasers of Left Foot Charley and, lastly, the wines of Brengman Brothers, a relative newcomer and one of the most compelling.

What initially impressed me most about Brengman Brothers’ wines was their sweeping range. This small, family-run operation produces four different wine label series. There's the entry level Runaway Hen line that uses grapes sourced both from Michigan (for Cab Sauvignon and Merlot) and the estate’s sister winery in Friuli Venezia Giulia, in northern Italy (for Refosco). There’s also an amaro made from 100% Michigan-grown Vidal Blanc, a Cab Franc ice wine, some very restrained and lovely Chardonnays, especially the unoaked bottlings, and their flagship wines, the Pentagon label series. The latter represent the most rigorously selected grapes, with pick times that result from daily ripeness assessments as well as deliberate matching of vineyard site with eventual wine style.

Most of Brengman’s current release is from the 2016 vintage, a winemaker’s dream confluence of growing and harvest conditions. As I tasted through the 2016 Pentagon series, I was struck by the ripeness, fruit density, and varietal purity of the wines, which in the case of the Rieslings, were not unlike those of Germany's already legendary 2015 vintage. This was the rare year when Brengman Brothers could produce wines that went deep into the ripeness spectrum, with noble rot allowing for Auslese and Beerenauslese styles, as well as an exceptional Gewürztraminer made in the Alsatian Selection de Grains Nobles (SGN) dessert wine style. Older vintages showcase drier-style Rieslings that likewise evoke Alsace in their concentration, power, and spice characters.

The wine that won me over, however, was one that hardly seemed to try. The 2016 Block 65 is a charming white blend with the ineffable appeal of a wildflower meadow in bright sunshine and something of that blossomy, grassy fragrance. It is a bright and aromatic wine ideal for spring and summer sipping. The blend is led by the high-toned floral notes of Viognier, with Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Gris lending herbaceousness and vivid citrus and stone fruit notes. A bright line of acidity elevates all the elements. Winemaker Robert Brengman feels the wine suggests star thistle honey, chamomile, apple (on both the nose and palate) and hint of ginger. It would pair well with an afternoon en plein air, a light lunch of salmon or roasted spring vegetables or even a richer chicken dish.

Grape Collective’s Valerie Kathawala talked with co-founder Robert Brengman about his family’s roots in Michigan and in wine, the Traverse Wine Coast soils and growing climate, the strengths of the 2016 vintage, inspirations for his winemaking, what sustainable/organic/biodynamic farming looks like in in northern Michigan, and what it means to make wine “on the edge of ripeness.”

Valerie Kathawala: How did you and your family get into winemaking?

Our family is third generation hospitality. We have the “love to make people happy” gene.  Our grandfather was the first in the food service industry, and dad was the first family entrepreneur breaking into the industry, at peak owning four restaurants in the greater Detroit area. We grew up knowing and appreciating wine from the restaurant perspective, believing that a gratifying reward for being alive is a great meal with great wine. [Brothers] Ed and Robert decided in 2003 to focus on just the wine after learning about the ideal cool-climate growing conditions in the Traverse Wine Coast region.

Our grandfather was the first in the food service industry, and dad was the first family entrepreneur breaking into the industry, at peak owning four restaurants in the greater Detroit area. We grew up knowing and appreciating wine from the restaurant perspective, believing that a gratifying reward for being alive is a great meal with great wine. [Brothers] Ed and Robert decided in 2003 to focus on just the wine after learning about the ideal cool-climate growing conditions in the Traverse Wine Coast region.

(Photo, left: Winemaker Robert Brengman and a friend)

What is your history in the Leelanau Peninsula?

We purchased orchard land in 2003, converted it to 25 acres of grapes and named it Crain Hill Vineyard. We added Cedar Lake Vineyard in 2008 and Timberlee Vineyard in 2012. All three vineyards are in the southeast corner of Leelanau County, where our research told us to expect warmer mesoclimates and microclimates with good airflow and a solid history of sensitive cherry, apple, and peach production at higher latitude than possible in most of the Midwest.

What does the terroir of Leelanau Peninsula give to your wines?

Thank the last Ice Age. We see sand, granite (field stone), gravel, loam, limestone with veins of iron in our dirt. The profile tends to be loamy sand (0-30 inches) and sandy loam (30-60 inches). Therefore well drained, good for inducing water stress on the vine, reducing vine vigor, and increasing fruit quality, but still with enough clay and sediments to provide some structure and fertility. Crisp (and even creamy), bright acidity is its signature takeaway from the dirt. The definition of flavors become pure when the vineyard and winemaking processes are in sync.

How do you select the clonal material you use in your vineyards?

There is a network of valuable local knowledge of what works and what doesn’t when it comes to material and grape selection. Smart people like Charlie Edson, Lee Lutes, Bryan Ulbrich, Tom Scheuerman, to name a few, who have gained tremendous experience and are at ease to share. It was a matter of asking, listening, and researching, then adding some personal likes that provided the input for our clonal material.

Some of your wines are strikingly Alsatian in terms of the varieties you work with and the style of the resulting wine. Is this your intention? The differences between warm, sunny, dry Alsace and cooler, damper Michigan are pretty stark. What are the commonalities that made you believe an Alsatian model could work?

After hearing you note the differences in weather between us and Alsace, I am actually glad we are somewhat ignorant of that comparison. We are always blown away by the weather that gets reported for our area. It must come from the airport in the city, where they are situated in a bowl and away from influence of the freshwater ocean that surrounds us on three sides. We're always puzzled when we see the weather posted for our area and feel strongly that there should be two readings — one for the city and one for the vineyards. It seems we always are warmer than the posted temps and experience a pattern of super dry conditions in July and August. Last season our fall was the warmest and driest that we’ve experienced since farming. As far as connecting to Alsace, we are fans of the wines and taste many of our favorites to enjoy and use as benchmarks for true Riesling, Gewürztraminer, and Pinot Gris taste profiles. A satisfying compliment is hearing a customer say that our Gewürztraminer is as close to Domaine Weinbach Cuvee Theo as any made on this side of the pond. Hey, the way we see it is that they invented it and know that their grapes are happy because of the history. We feel the same in that our grapes are happy and delivering what is true to the profile. And the fact is Alsace is farther north, at 48° N, than we are, just south of the 45th parallel.

Are there other wine regions that inspire your winemaking?

Burgundy for our Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, of course, and taking interest in the British fizz movement as we see that as another good fit for our fruit. Also, you can’t ignore the Loire because our Chenin Blanc, Muscat and Sauvignon Blanc are really liking it here. Finally, Tokaj is another region that we see as common ground because we’re in the early understanding of noble rot as a pattern here, and why we should embrace it.

Please elaborate on your concept of Grand Crus as the "earth's erogenous zones"?

This is so true with any great winegrowing region in that there are just better places to plant and grow than, say, the dirt just a mile or so down the road. The plants know when the dirt, pitch, elevation, wind patterns, climate are just right for them and, with the right care, will perform year after year with ripeness. Classification is a good thing if it’s based on history and the performance of vines on a certain piece of ground. The way we see it is there are vineyards that should be focusing only on bubbly, as non-chaptalization ripeness for still wines is tough.

Tell us more about the origins of Block 65 and what the 2016 vintage contributed to making the wine so beautiful.

We set out with this special wine to first pay homage to our brother Bert, who succumbed to brain cancer in 1998. He was our role model when we were kids by being a solid football player in college then excelling at a career in coaching. He made the number 65 famous for our family.  It was his jersey number, and the rest of us wore it proudly when we played. We planted the grapes that make up this unique blend in Blocks 6 and 5 on the southwest slope in the warmest microclimate at Crain Hill Vineyard. Block 5, planted to Pinot gris, slopes to the south and sits to the east and below block 6. It does not generate the warm microclimate that block 6 gets, so we felt that the Pinot Gris was the correct variety for this spot. Block 6, planted to Viognier and Sauvignon Blanc, slopes to the southwest and is completely protected from the cool northwest winds by a natural ridge of hardwoods to the north. It is the warmest site on Crain Hill Vineyard with good ripening conditions for these later ripening varieties. We have only missed our ideal chemistry in two out of ten years of harvesting in this block.

It was his jersey number, and the rest of us wore it proudly when we played. We planted the grapes that make up this unique blend in Blocks 6 and 5 on the southwest slope in the warmest microclimate at Crain Hill Vineyard. Block 5, planted to Pinot gris, slopes to the south and sits to the east and below block 6. It does not generate the warm microclimate that block 6 gets, so we felt that the Pinot Gris was the correct variety for this spot. Block 6, planted to Viognier and Sauvignon Blanc, slopes to the southwest and is completely protected from the cool northwest winds by a natural ridge of hardwoods to the north. It is the warmest site on Crain Hill Vineyard with good ripening conditions for these later ripening varieties. We have only missed our ideal chemistry in two out of ten years of harvesting in this block.

(Photo, right: Blocks 6 & 5 of Brengman Brothers' Crain Hill Vineyard)

The 2016 vintage gave us perfect ripeness for this blend. The Viognier is the largest share, at 40%, followed by Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Gris, at 30% each. Subtle notes of star thistle honey, chamomile, apple (on both the nose and palate) with hint of ginger give Block 65 a special signature. It is well balanced with a perfect level of sweetness to please; very juicy with a nice finish.

Do you have an ideal food pairing with this wine?

Besides air (makes a great wine with conversation!), chicken piccata is a perfect match for this blend.

What about the 2016 vintage made it so ideal for your wines?

As winter was coming to an end, we were excited to realize we had just experienced a very mild one. As with any season, we were prepared with burn piles, nervous about the potential for spring frosts that could take out the crop. Blasts of cold were fresh in our memory as a few weeks before buds were starting to swell, we had a week of cold that was perfect for allowing us to cold stabilize and finish our 2014 and 2015 wines still in barrel and tank. Pruning season was especially grueling as we tied down all new canes for the entire vineyards after the two previous harsh winters. We began to get really excited about the season after the last frost scare missed us, and we realized we didn't even need to light up our burn piles, which after pruning and tying ended, got moved to the back to convert to bio-char to feed the vineyard.

As the summer progressed, warm sunny weather with a rainstorm every four or five days like clockwork, the mood turned cautiously optimistic that with a good fall we had the potential for a truly great season. Our vineyard crew being all fired up decided to go the extra mile — implementing selective hand pulling of leaves during bloom in some blocks and a new impressive but very labor-intensive canopy management program to push quality to a new level.

With the beautiful weather holding, we held out on picking most blocks until late October to build full ripeness. As we began to pick Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, it quickly became evident that our avant-garde leaf pulling technique had reduced the size of our crop but paid off beautifully in intensity and concentration of flavor in both. By the time we finished our Bordeaux varietals we realized we were at a beautiful stage of ripeness in much the rest of our vineyard. It became a race to pick Blocks 6 and 5.

By the time Halloween was over, and we realized that specific clusters of our Riesling had been blessed with noble rot, our stalwart vineyard crew set off on the laborious task of hand selecting and picking all of the noble rot clusters, allowing us to have a true Beerenauslase. Then, thankful to be done with hand-selecting bunches, the crew shifted gears the next day to start picking our remaining Gewürztraminer, only to discover that a good portion of that had been blessed with noble rot as well.

In retrospect, spring, summer and fall were about as good as it gets for ripening. The best degree-day recording for this new century was in 2005, and 2016 ended 5% warmer according to the weather data depot. Our perfect soils, hand care, attention to detail, boutique processes and combining the best of Old World traditional viticulture with proven modern techniques is why we get great wines in good years and truly historic wines in great years.

Which sustainable practices in your vineyards are you proudest of?

(Photo, right: Grazing sheep tend the cover crops and contribute to soil health in the sustainably farmed vineyards at Brengman Brothers)

What are the challenges to organic/biodynamic viticulture in the Traverse Wine Coast region?

I am a big fan of biodynamic farming and believe it will work here. But it is so demanding to stay in front of the pressure, and we’re pretty good at the sustainability process. We are discussing a plan to put in place a test section in one of the vineyards so we can become confident and more experienced in the steps for success for biodynamic.

Finally, where do you see Michigan winemaking 10 years from now?

Being on the edge of ripeness, I think winemaking will become more focused and we will see a switch from a not-so-serious-tourist-wine-region to a serious-fine-wine-region where sommeliers, collectors, and wine appreciators will seek the tasting experience and purchasing wine as the main reasons to visit. For them, the beautiful National Park and beaches will be a bonus, but secondary.

For more on Michigan wine, check out :

Dorothy Gaiter's column on Left Foot Charley

Grape Collective's interview with Lee Lutes of Black Star Farms

---

Sources: The Early History of the Michigan Wine Industry, Sharon Kegerrreis and Lorri Hathawa