Michael Silacci, the first solo winemaker in the history of Opus One, the famous Bordeaux-style blend made in Napa, is himself an interesting blend. He’s large part Jedi Master and teddy bear, but also, at his core, a disrupter. How else would you explain why, new on the job, he had wondered, “What can I do, the one thing I can do, to end my honeymoon here and have the biggest impact on wine quality?”

Most people want to extend their honeymoon, but not Silacci (photo right), 63, who has been with the iconic winery in Oakville, California, for 17 years and has since 2004 been solely in charge of winemaking and the vineyards. Opus One, founded in 1979, is the groundbreaking creation of Robert Mondavi, whose formidable drive helped ignite America’s love of California wines, especially Napa Valley ones; and Baron Philippe de Rothschild, who labored indefatigably to see Château Mouton Rothschild of Bordeaux elevated to First Growth status in 1973. Their goal was to make one great wine, something akin to an American First Growth. Both men are gone, and Mondavi’s half of the business has been owned since 2004 by Constellation Brands, the third-largest beer company in the U.S. and owner of more than 100 brands of alcoholic beverages.

Some changes are afoot. A year ago, Napa officials gave the winery permission to double its current annual production of around 25,000 cases. However, winery officials told us that there are no plans to increase the amount of wine they make, even though they sell every bottle. The expansion is necessary, they said, because they need more space for more barrels, administrative offices and customer service spaces.

In fact, Opus One CEO David Pearson, the first person to be solely responsible for the company, has said he’s considering raising the wine’s price in the U.S. to be closer to its price in Asia. Its current vintage, 2013, sells at the winery for $295 (with a six-bottle per person limit). Wine-searcher puts its average price at $308. Wine-searcher puts the average price in Japan at $348 with some stores in Japan selling half bottles for $210 and some selling full-size, 750 ml bottles for more than $400.

So by the time Silacci was hired and made his first Opus, the 2001, the proprietary Cabernet Sauvignon-based Bordeaux blend had been famous for decades. Yes, it had had its ups and downs, but it must have been gutsy to make a significant change in its workings. However, looking back, apparently Silacci’s honeymoon-breaking action was pivotal, laying the groundwork for its present day success.

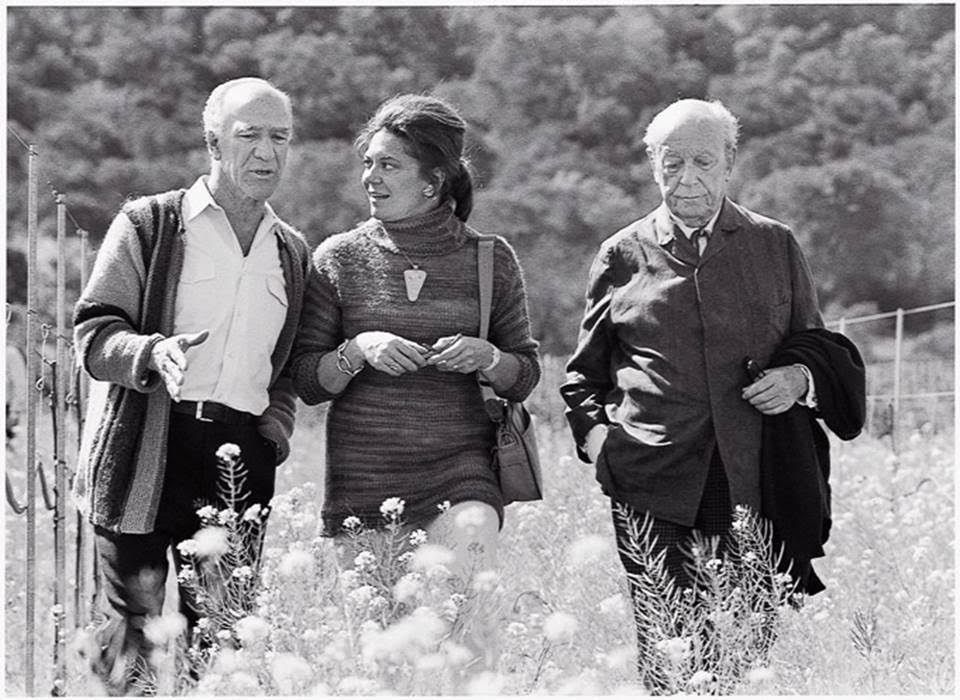

Robert Mondavi, Baroness Philippine de Rothschild, Baron Philippe de Rothschild

A little history: Mondavi, who died in 2008 at the age of 94, and Rothschild, in 1988 at the age of 85, had begun talking about a joint project in 1970. Tim Mondavi, one of Robert’s sons, and Mouton’s then-winemaker, Lucien Sionneau, made the first Opus One, which was called Napamedoc, in 1979 at Mondavi’s winery across the street from Opus’s current stunning location. After Sionneau retired, Patrick Léon joined Château Mouton Rothschild as winemaker and made Opus One with Tim Mondavi.

The partnership between Robert Mondavi and Baron Philippe de Rothschild was unveiled in 1980, with great fanfare—one of Mondavi’s specialties--and high expectations. Rothschild, from a long line of aristocrats in banking, was lending his credibility to Napa’s young wine industry. When the 1979 and 1980 were released in 1984, together constituting what the winery considered its first release, it created a new category of American wines, winery officials say, the ultra-premium level, selling for a sky-high $50 a bottle. (In 1981, a mixed case of the 1979 and 1980 presold at the first Napa Valley Wine Auction for $24,000, at the time the highest price ever paid for California wines.)

After Mondavi sold his 50% interest in Opus One to Constellation, Baron Philippe’s only child, Baroness Philippine de Rothschild, and Constellation agreed to a new business structure. That agreement, which continues despite the Baroness’s death in 2014, granted Opus One autonomy over domestic and international sales and administration, but most important, over winemaking and vineyard management. That means Silacci, who worked with two of California’s most demanding winemakers, Warren Winiarski at Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, and with the late André Tchelistcheff at Beaulieu Vineyards, and at wineries in Oregon, France and Chile, no longer shares those winegrowing and winemaking duties. He has final say over how Opus is farmed and what it tastes like. He has viticulture and enology degrees from UC-Davis and the University of Bordeaux, and he strongly believes wines should reflect the vintage and therefore be variable. We couldn’t agree more. If you want consistency, drink a Coke.

“The most important thing that goes into the glass comes from the grape and the vineyard, and the vineyard reacts differently from year to year to the weather,” he told us. The winery uses the five red Bordeaux grape varieties, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot and Malbec. They are grown in Oakville’s acclaimed clay loam soils with gravel “ideal for draining and deep rooting,” according to the winery’s materials. The wines are aged in French oak.

From left to right: Michael Silacci, Opus winemaker; Willis Loughhead, executive chef of the InterContinental New York Barclay Hotel in his kitchen; J. France Posener, Eastern Division Manager for Opus One for 30 years, Dorothy Gaiter and John Brecher. Silacci took the selfie.

John and I were never particularly fond of Opus One, finding it overpriced and over-rated. That changed in 2004 when we did a blind tasting of 50 well-known, very expensive American Cabernet Sauvignons and Bordeaux-style proprietary blends from the 1999, 2000 and 2001 vintages for our column, Tastings, in The Wall Street Journal.

To our great surprise, our best of tasting was the 2000 Opus One, and the 2001 a close runner-up. Given our history with the wine, we were floored. We had set our limit at $160, which precluded our tasting of Screaming Eagle, and would today fall very short of the going price of Opus One. The 2000 is 84% Cabernet Sauvignon, 6% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc, 3% Malbec and 2% Petit Verdot. The 2001 is 87% Cabernet Sauvignon, 6% Merlot, 3% Malbec, 2% Cabernet Franc, and 2% Petit Verdot.

Opus is so successful today that “we could sell everything we make in Japan,” France Posener, Opus One’s Eastern Division manager, told us. In her 30 years with Opus, she said she had never seen a year when all of its wines were not purchased. Half of Opus One’s annual production is exported. Michelle Lawlor, of Cru in Hong Kong, told Decanter.com in September that she sold out of the store’s 2013 allocation within hours. “We could have sold double the amount and are currently looking for more.” Posener said that Opus One is the only American wine sold by French negociants. It’s available in 100 countries.

Since Constellation became half-owner, some of the wine’s fans have feared a bump up in production and a dilution of the brand. Both Silacci and Posener told us there would be no increase in production, with Silacci averring that there might only be a “slight increase” due to greater vine efficiency. One change is that Opus One’s longtime second label, Overture, a nonvintage Bordeaux-style red that used to be sold only at the winery, will now be distributed, Silacci said (at $117, according to wine-searcher).

Looking back at Silacci’s arrival, perhaps the ending of the honeymoon was the beginning of a turnaround and it had to do with building a team and empowering people, disrupting the old, with Jedi Master and teddy bear stuff.

“When I was hired, I was told to make a change, but not too big of a change,” Silacci told us over an eye-opening, vertical tasting of Opus that was paired with stunning dishes prepared by Willis Loughhead at the recently restored InterContinental New York Barclay hotel in Manhattan. Posener, whom I’d met a few months ago, arranged the evening and joined us in the chef’s kitchen.

As a nod to our change of assessment in 2004, they opened the 2000 and the 2001 (both still beautiful) and the 2010, 2012, and the 2013. The 2000 reminded me of an old Bordeaux -- crushed rose petals, cedar, and nice minerality, chewy yet elegant, an endlessly fruity finish, pretty spectacular, a beautiful dowager. The 2001 was from the same footprint but with more body. Amazing freshness, spice, licorice. Not as explosive as the 2000, but still intense after two hours. The 2010 was still a youngster, flexing its youth with a dense purple color and mouthfeel and spices. (84% CS, 5.5% each Merlot and CF, 4% PV and 1% Malbec). It looked different from the others, like everything the grape had was in that glass, nothing lost. Blackberries, blueberries. The 2013 we could have drunk all night. (79% CS, 7% CF, 6% each Merlot and PV, and 2% Malbec.) It had marvelous structure with layers of complexity, rich earth, firm tannins, lovely now but fabulous in the future. The only time all night that Silacci grew tense was when Posener, against his firm objection, told us that James Suckling had awarded the 2013 a score of 100. The 2012 was explosive in the mouth, intense and earthy, full and vibrant. (79% CS, 7% CF, 6% each PV and Merlot and 2% Malbec.)

Starting with a 2012 Chassagne Montrachet Domaine Bernard Moreau et Fils with softshell crab over scrambled egg with sauce Americaine, we then went on to the Opuses in the order above with duck and cherries and truffle-salted popcorn, to Catskills veal with asparagus and mushrooms with the 2010 and the 2013, to Pennsylvania beef with black garlic gnocchi with the 2012 last. Chef Loughhead said he tries to source everything from within 120 miles of the green-focused hotel. The wine, he said, was an obvious exception, but some of the herbs came from the garden on the 700-room hotel’s roof.

Silacci said he was thinking of his bosses’ permission to make a change as “a kind of ‘be careful, you might get what you wish for’ thing.”’

During the interview process and multiple visits to the vineyards, he had decided that the vines should be “severely” pruned.

“I thought we needed to go in and sort of start from scratch because what I felt the wine needed was an increase in concentration and a lengthening of the finish. Those were the two things I thought Opus needed help with,” he said.

We were happy to hear that because over the years, especially in the 1990s, before we wrote about wine, we had concluded pretty much the same thing. It also didn’t help that for a few years in the 1990s, the winery had to deal with Brettanomyces, a yeast that makes wines taste a little funky.

However, the severe pruning, which must have had an impact on the bottom line, isn’t what ended the honeymoon. This did: Opus One’s fruit came initially, naturally, from Mondavi’s land. He had sold a portion of his highly desired To Kalon Vineyard to the partnership and his employees worked the partnership’s expanding vineyards. But not exclusively Opus One’s vineyards; they worked other Mondavi properties as well, for other Mondavi wines. That was a problem for Silacci, he told us. (Today half of Opus One comes from two parcels of To Kalon and half from the vineyards that surround the winery.)

“When I arrived at Opus I kicked tires, walked around, just listened to people, attended meetings, tasted wines, I tasted a couple of verticals of Opus and I came up with a mantra: enhance tradition, maintain innovation. And that was my goal.”

Then he asked himself what he could do to end the honeymoon. After a lot of thought, he concluded, “It was putting together a vineyard team that only worked at Opus One.”

“They would send in two or three crews a week and alternate them, rotate them, and I asked why they had people changing all the time, and they said they wanted the vineyard teams to have perspective. So they would see people in Carneros and Oakville.

“And I said, I don’t mean to be rude but I think that the only person who should have perspective here is me. Because how can someone prune the vines in Carneros for Chardonnay and come and prune vines for To Kalon for Mondavi Reserve or Opus and see differently? I said I wanted 24 people. I calculated how many people we needed to start pruning the first Monday after New Year’s and finish by the 10th of March with one week loss due to rain.

“And they agreed, and that ended my honeymoon because I didn’t ask, I didn’t go in for permission. We did it. I talked them into it,” he told us.

“Actually, they said, ‘Well, we can do this but we’ll do it after harvest’ and I said no, no, no. It has to be done right away so we don’t lose any more time. And when Tim and Patrick come next, I want them to see that there’s no seam between me and the vineyard workers. When I I walk out into the vineyard, I want the vineyard workers to know who I am and I know who they are.

“I was called into the principal’s office, with the two half-bosses, the two co-CEOs, each thinking the other had orchestrated this. And I said no, it was me and I explained why. So I was dismissed [from the room]. They were shocked. Then I was brought back, they called me back in and said, ‘OK, you’re not working at Stag’s Leap anymore, you’re not making your own decisions,’ which wasn’t entirely true. They said, ‘You have to reach consensus.’

“I said, OK, I knew that, but it would have taken six years to get that because there’s so much back and forth,” Silacci recalled.

So I asked the natural next question. Is there still back and forth?

“No,” Silacci said, “Constellation was the catalyst for our independence.”

With the new ownership agreement came the realization that it was time for the owners to pull away, to loosen the reins, he and Posener said. The board of directors has three members from Constellation and three from Rothschild. “Basically, they can affect what I do, what any of us does, by saying, ‘We can’t afford to spend money on that project or that piece of equipment,’ but they don’t,” Silacci said.

What Silacci did with those 24 vineyard workers, he believes, helped make Opus One the success that it is today. He developed levels of training to encourage workers to feel more responsibility for the wines and the vines and to be able to supervise others in their work. He said he knew they understood the “mechanism of winemaking” but he wanted to encourage a deep connection with the vines. So he divided the winery’s staff into two teams and gave each responsibility for 22 rows “in our best vineyards to prune, to sucker, to thin, to do green harvests and we taught them to taste and make harvest decisions,” Silacci said. The team that made the better wine—each team got the other team’s wine as well as their own--got some of it added to Opus One.

Silacci said he organized the teams so that they weren’t comprised of all friends, which forced consensus building, and each year the teams get three new people: a vineyard worker, an office worker, and a guest-relations tour guide.

The teams’ first task was pruning. “I wanted vineyard workers, who often didn’t speak English very well, to really understand that they were equals so they would lead the teams in pruning,” Silacci told us. “They taught everyone to prune so they had a position of authority and responsibility right off the bat. That way, they would never feel they weren’t part of the team or equal because of language.”

At one point, invariably, the teams would turn to him for guidance, saying, “We don’t make those decisions, you tell us what to do,” Silacci said.

His response? “I said that’s the problem. Until everyone is engaged in the pursuit of absolute wine quality, we can’t get to the next level.”

So he has raised people up, including mentoring a lot of women who have gone on to be winemakers at other places, and they, he said, have raised him up. This love of mentoring, of teaching people, and being mentored and taught is deeply ingrained in Silacci, a California native who said his first career choice was to teach kindergarten because young children “are so open to everything.” He has a daughter who is 29 and a physical therapist. Her mother is from France, where he first learned winemaking.

We told him that he should write a book about managing and I told him that the New York Mets really needed him. How did he learn how to get the best from people, to make them feel a part of the whole, to do what’s in their best interest and his?

“First of all,” he said, “I love blending, so I love blending vineyards—we do a lot of co-fermentation of varieties, and I love blending wines and people. I love putting teams together. Realizing that teams make better decisions than individuals, you need a strong leader to make sure the team is going in the right direction.”

Then extending his arms to make the point, he added, “If you think your field of vision as being your field of strengths, and all of the things that I do that I don’t realize are my weaknesses because they’re in my blind spot, you need people in your field of strength, someone standing directly behind you with their strengths and weaknesses, somebody here, somebody here, somebody here. Pretty soon you create a circle with everyone using their strength, seeing things others don’t maybe, to make the team function better.”

Later, in response to a question about mentoring, Silacci emailed this to me: “I posted the following on Facebook about my mother on International Women’s Day: My mother grew up on a dairy 7 miles east of Gilroy. In the sixties, she raised 3 knuckleheads as a single parent on the salary of a bookkeeper. Now in her eighties, she volunteers at Gilroy Gardens [a family theme park] and at the hospital gift shop. She chauffeurs great-grandchildren and friends without wheels around town to school, church, and doctor appointments. She bakes muffins and brownies to take to all of the above and to the women at the beauty shop. She is my Rosie the Riveter.”

And this about another mentor, André Tchelistcheff, who had retired from Beaulieu but as a consultant had weekly meetings with Silacci when Silacci was viticulturist for BV, Inglenook, Christian Brothers and Quail Ridge.

“Once a week I would pick André up at his house to visit the vineyards of Beaulieu. He and I would talk for 30 to 40 minutes about what the two of us would do to make BV great again.”

At the end of the third session, he wrote, he told Tchelistcheff, “André, I don't think you are being paid to pat me on the back and tell me what a great job I am doing and how our vineyards are excellent. You should critique the vineyards.”

“Do you know what you are asking me to do?’ Tchelistcheff asked him. Silacci nodded.

“If I do this, will we still be friends at the end of every visit?’ Tchelistcheff asked him. Again, he nodded.

“He reached out, and we shook hands to seal the deal. At some point during each visit, André would emotionally punch me in the nose. I would be stunned, as if I were physically punched. The smell of imaginary blood filled my nostrils,” Silacci wrote. “As it dissipated, the essence of that day's lesson crystallized. Younger consultants leave you dizzy with their stream of never-ending consciousness. The great ones, like André, will say a few words or sentences during a three-hour session that are priceless. André filled my mind and imagination. He also taught me invaluable skills like how to taste grapes to determine ripeness.”

Of the wines on the table, Silacci’s favorite was the dense 2010, not because he thought it tasted best, but because through his intuition and observation and the ingenuity of one of his assistants whom he’d mentored, they were prepared when there were two heat waves. “It was like being in a tae kwon do match with Mother Nature, taking whatever she gave us and channeling it into something positive,” Silacci recalled. Watching his assistant struggling to find a solution to the heat’s effect on the vines, he told us he’d said to her, “I will never let you fail.”

Now that’s leadership and trust. Effective, apparently, in every enterprise.

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.

Read more columns from Dorothy J. Gaiter on Grape Collective

(Homepage Opus One Banner Art By Piers Parlett)

To puchase Opus One follow this link on Winesearcher to the retailers that carry it.