One hundred years ago this week, France launched its first major offensive against Germany in World War I. The fight took place in the winegrowing region of Champagne, which the German army had invaded just weeks after hostilities broke out. Nearly 200,000 lives were lost in the three-month battle. Champagne witnessed some of the war's heaviest fighting. The region's two largest cities, Reims and Epernay, were bombarded for three years. Locals took shelter in the caves under houses like Veuve Clicquot, Krug, and Taittinger. The vineyards became battlefields. Yet production continued.

One hundred years ago this week, France launched its first major offensive against Germany in World War I. The fight took place in the winegrowing region of Champagne, which the German army had invaded just weeks after hostilities broke out. Nearly 200,000 lives were lost in the three-month battle. Champagne witnessed some of the war's heaviest fighting. The region's two largest cities, Reims and Epernay, were bombarded for three years. Locals took shelter in the caves under houses like Veuve Clicquot, Krug, and Taittinger. The vineyards became battlefields. Yet production continued.

Where bombs could be avoided, women and children harvested grapes. Famously, Jeanne Krug sought winemaking advice via post from her husband, Joseph II, who was a prisoner of war. Praising Krug as a "brave lady," the British sales representative for the Champagne house would later remember selling "the entire cuvee of 1915 in record time."

A full century has passed since the Battle of Champagne. But wine remains inextricably tied to conflict. And the bottles that survive continue to offer a window to other times and places.

A full century has passed since the Battle of Champagne. But wine remains inextricably tied to conflict. And the bottles that survive continue to offer a window to other times and places.

I’ll never forget the evening I tasted a perfectly cellared bottle of Bordeaux from 1919. The wine still had life in it; it was delicious and utterly fascinating. But more importantly, the wine inspired a conversation about the lives of those who made it. The First World War officially ended in 1919, so that wine was made while cleaning up from the wreckage and hoping for a brighter future.

Europe, of course, only had a brief respite. Fighting would once again ravage the continent just 20 years later.

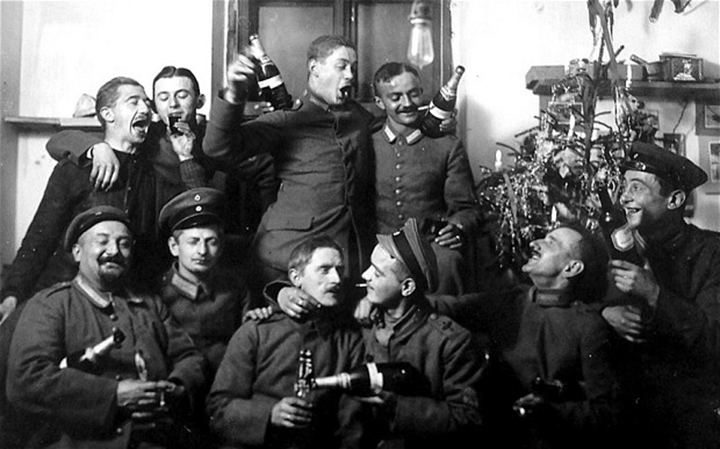

The Hugels, a winemaking family in Alsace, still recall the Christmas of 1939. A year earlier, the Nazis conquered Austria. After seizing Czechoslovakia in 1939, Hitler signed pacts with Italy and the Soviet Union. The world knew that another war was just around the corner.

As Donald Kladstrup and Petie Kladstrup wrote in Wine and War: "On Christmas Eve, the Hugels gathered together… but it was a somber affair. In previous years, the house had always been decorated, everyone exchanged gifts and then sat down to a sumptuous dinner that included some wonderful wines. But not this year. No one was in the mood. Everyone feared that this would be their last Christmas as French citizens."

The story of war and wine continues today.

Consider Domaine de Bargylus, the only commercial winery in Syria. Located on a mountainside in the port city of Latakia, where winemaking dates back nearly 4,000 years, the winery was launched in 2003, when Karim and Sandro Saadé sought to honor their father by planting a first-rate vineyard. Like 10 million other Syrians, the Saadés fled their homes to escape the bloody uprising against Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. So today, they run their winery from Beirut, in Lebanon.

Consider Domaine de Bargylus, the only commercial winery in Syria. Located on a mountainside in the port city of Latakia, where winemaking dates back nearly 4,000 years, the winery was launched in 2003, when Karim and Sandro Saadé sought to honor their father by planting a first-rate vineyard. Like 10 million other Syrians, the Saadés fled their homes to escape the bloody uprising against Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad. So today, they run their winery from Beirut, in Lebanon.

The brothers can't return home; as businessmen, they're prime targets for kidnappers. Instead, they issue directives to their staff via phone and email. Occasionally, they'll even hire taxi drivers to shuttle grapes across the border.

Lebanon has been spared from most of Syria's bloodshed. But the owners of the 47 wineries in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley recognize that war is never far away. Indeed, the region's eastern edge harbors fighters from both ISIS and al-Nusrah Front.

With the holidays now here, many of us will spend the coming days surrounded by family and friends, eating great food and drinking great wine. Just as wine is no stranger to war, neither is the world. So this holiday season, be sure to give thanks.

David White is the founder and editor of Terroirist.com, which was named "Best Overall Wine Blog" at the 2013 Wine Blog Awards. His columns are housed at Grape Collective.