It’s fun to be in the presence of a restless, searching mind, and absolutely thrilling when that mind is focused on wine. Ernst Loosen (pronounced like LOH-zen), who brings to mind Mick Jagger with his rakish, dissolute air, possesses such a mind. Known as the King of Riesling --- his family has owned vineyards in the Mosel Valley of Germany for more than 200 years -- he is at his core a scientist.

Underneath those graying curls, puppy-dog eyes and the other day a plaid jacket with a perfectly accessorized apricot-colored scarf, he’s a methodical scientist, but with the energy of a comet. Talking with him is like tumbling down some wonderful rabbit hole. So many tantalizingly winding trails, razor-sharp turns and jubilant, richly colored nooks. Rewarding like a good, long book.

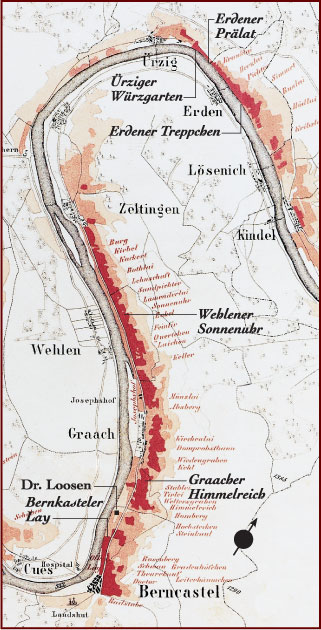

It’s this searching, exacting mind that has made Loosen such a famous and reliable name in Riesling from the Mosel and Loosen, 57, an ambassador for the region and a nudge to others to up their game. He and his wines have won accolades and a growing following, especially for the range from Dr. Loosen, the most historic and prestigious part of his holdings. The estate’s house is in Bernkastel, along the Mosel River.

Loosen is so enraptured by experimentation that he kept a 1981 Wehlener Sonnenuhr Riesling in barrel for almost 28 years—28 years!-- just to see what would happen to it. “I call it my Benjamin Button wine,” he said at a tasting of it and his six dry, single-vineyard wines last week, referring to the 2008 movie in which Button (Brad Pitt) ages in reverse. “It just gets fresher and fresher.”

It did! While the other wines that went from 12 months to 36 months in casks were stunning, they were the dry Grosses Gewächs or “Great Growths,” a fairly new qualitative designation, I was stuck on this 1981. It was a bright, pale yellow, not gold as I expected with that much age. It reminded me of honey, peaches and white flowers and it still had a green apple-like acidity and a persistent minerality from the blue slate from which it grew. I was amazed. His winemaker, Bernhard Schug, “forced” him to bottle it in 2008, Loosen said. If he hadn’t, it would still be in cask. Furthermore, the government won’t allow him to sell it, he said, because it has no laws governing such a creation. So it was indeed priceless.

“This is definitely not a business model to keep,” Loosen said to a round of laughter.

Although there is no officially recognized cru system in Germany for vineyards, as there is in France, Dr. Loosen’s six major vineyards were designated for tax purposes in the 1868 Prussian classification of Mosel vineyards as Erste Lage, similar to grand cru. These diverse sites produce the company’s highly prized, single-vineyard designated, old-vine wines.

From simple entry-level fruity Rieslings, to majestic dessert wines including Eiswein, to those ultra-premium reserve Grosses Gewächs, the company’s reach is far. The wines are available in about 90 countries, with winemaking collaborations in Oregon (Pinot Noir at Appassionata with Jay Somers from J. Christopher Wines) and Washington (Riesling, Eroica, with Chateau Ste. Michelle). Through Loosen Bros. USA, with his brother Thomas, he imports Loosen’s labels, wines from other like-minded German winemakers, and those from a Burgundy producer. Loosen Bros. Dr. L Rieslings are entry-level wines, including a sparkler, made from purchased grapes. In 1997, Loosen purchased J.L. Wolf, a wine estate founded in 1756 in Pfalz in the southwest, that he renamed Villa Wolf. In addition to affordable Rieslings, Villa Wolf makes Dornfelder, a rich, earthy red, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Noir (Loosen’s second love after Riesling), a Pinot Noir Rosé, Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris.

The complex, dry, reserve Grosses Gewächs are a passion for Loosen because he’s trying to recreate the wines of his great-grandfather, when Rieslings from the Mosel, he said, fetched more money than First Growth Bordeaux. He calls one Grosses Gewächs “Homage.” His father and grandfather’s wines were fruity and sweet, what Germans wanted after the wars, he said.

Although both of Loosen’s parents came from wine-making families -- his mother is related to the famous Prüms -- he had planned to be an archeologist. Winemaking also was a sideline for his father and grandfather. They were into politics and other businesses. His father was a lawyer and the original Dr. Loosen, whose name Ernst decided almost 40 years ago to use for his highest-end brand.

Even though Roman ruins fascinated him, his dad insisted that he study oenology at the Geisenheim wine school. Still, as soon as he earned his diploma, he enrolled in the archeology program at Mainz University and would have earned a degree had his dad not become ill with hepatitis. Returning home and armed with new ideas about winemaking-- lower yields and organic fertilizers and the like-- he and his dad clashed often. Unlike his great-grandfather, who was a tirelessly innovative winemaker -- he kept wines a long time in cask -- his dad and grandfather had always hired winemakers and had never invested much money in the vineyards.

One day when Loosen was in one of the cellars, Schug, a friend of his older brother, asked him for a job. He had no experience in winemaking, Loosen told me. What “Bernie,” as he calls him, did have was a diploma in exotic pig diseases---close enough, Loosen decided, at least another brain with a searching, scientific bent.

Just as harvest was getting underway in 1987, his father’s old crew quit. They were upset over “the way I wanted to do the selection,” Loosen told me, explaining that he wanted them to sort out the best, mature grapes from less ripe ones when they picked, a painstaking process that they had never done. “If I had apologized and taken them back, I could never do what I wanted to do and if I fired them, it would have cost me a lot of money” in severance. So he let them quit.

There was one really, really big problem, though, with them leaving. He didn’t know which vineyards were his family’s. “I know that sounds so stupid,” he said, but typically, he explained, several families owned plots, rows of vines, in a vineyard. So he and Schug hatched a plan. They would wait until everyone else had picked their grapes and what vines were left with fruit had to be Loosen’s.

Then a wonderful thing happened. The weather turned beautiful, ripening the grapes just so. Because they were the only winemakers with fruit still on the vine, “we were the only people who made a Spätlese that vintage,” referring to wines of a certain ripeness.

A short time later, his mother called all of her offspring together, Loosen and his three brothers and two sisters, and told them that their father was dying and that she no longer wanted to own the estate. She had a buyer who was ready to take it over if they didn’t want to buy it.

“And that was when my brothers and sisters told me ‘you have to take it, you studied archaeology, you’ll never get a job. You’re going on social welfare. We’re not supporting you. You better take the winery. That way you’ll have a job.’ And so I said, ‘Yeah, I’m happy take it.’’’ And so he gave up the idea of completing his archeology degree. (Loosen, who is divorced with no kids, has no plans to retire but is nonetheless grooming his oldest nephew, Daniel.)

When Loosen took over in 1988, he accepted the keys to the estate, $500,000 in debt, and no customers. “I had to rebuild from scratch,” he said. Loosen also discovered that because his father and grandfather had neglected the vineyards, they hadn’t followed their neighbors and pulled out old vines and planted new ones. His youngest vines were 60 years old, the oldest more than 100. What’s more, they were ungrafted, growing on their own roots, because they had never been attacked by phylloxera, which can’t thrive in slate soils. It was as though he’d struck gold.

“I always saw it, when I took over, as a huge asset,” he said, “but in our country, the people say ‘Oh, after 25 year the vines don’t make enough ... they don’t give enough yield anymore and then you have to plant new. You will never succeed with that, because it’s so expensive.’ I said what are these guys talking about? I mean, I have 100-year-old vines and that’s the best thing in the world. Never in my life will I experience this again if I plant new, and so I kept it. That was one of the most, for me, traumatic decisions, because everybody in the valley said, ‘Oh, you have to plant new. You can't stay with the old vines.’’’

“They don’t bring enough fruit,” he admitted, “but they bring excellent fruit.”

The next year, in 1989, Der Feinschmecker , the most influential wine publication in Germany, named one of his wines “Best Dry Riesling of the Year.”

“A lot of people had been betting on me that I would go bankrupt in- between two and three years, and so they all have lost the bet, at least,” he told me. “That was a big help, to win that prize.”

I can’t imagine how sweet that was.