Bekaa Valley covers almost 90% of the wine production in Lebanon with winemaking in the region dating back 6,000 years. This long, narrow, north-south valley with high-altitude (3,000 ft) has a unique mesoclimate and terroir thanks to the mountains enclosing the valley and the melting water from the mountains nearby.  The rain shadow effect cast by Mount Lebanon, a 100-mile mountain range, creates reliable sunshine (approximately 240 days of sunshine per year) and dry climate. The melting water from Mount Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon Mountains is another great source to get fresh water despite the limited rainfall (only 25.2 inches precipitation per year). These mountains serve as great protection to the Bekaa Valley from the deserts to the east and maritime rains to the west. Summer is generally hot but it cools down in the evening thanks to the altitude and breezes circulating throughout the valley. Furthermore, almost no rain in summer is ideal for grape growing. The soil of Bekaa Valley is rocky and gravelly, covered by a layer of clay-chalk and limestone. Because of all these advantages, Bekaa Valley truly embraces Mother Nature and provides grapevines an ideal place to grow. No wonder Faouzi Issa says, “The Bekaa Valley is one of the best areas to grow grapes in the world.”

The rain shadow effect cast by Mount Lebanon, a 100-mile mountain range, creates reliable sunshine (approximately 240 days of sunshine per year) and dry climate. The melting water from Mount Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon Mountains is another great source to get fresh water despite the limited rainfall (only 25.2 inches precipitation per year). These mountains serve as great protection to the Bekaa Valley from the deserts to the east and maritime rains to the west. Summer is generally hot but it cools down in the evening thanks to the altitude and breezes circulating throughout the valley. Furthermore, almost no rain in summer is ideal for grape growing. The soil of Bekaa Valley is rocky and gravelly, covered by a layer of clay-chalk and limestone. Because of all these advantages, Bekaa Valley truly embraces Mother Nature and provides grapevines an ideal place to grow. No wonder Faouzi Issa says, “The Bekaa Valley is one of the best areas to grow grapes in the world.”

Domaine des Tourelles, located in Chtaura at its highest altitude, is one of the oldest commercial and highly acclaimed wineries in Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. François-Eugène Brun, a French engineer who fell in love with wine founded the domaine in 1868. Under the Brun family’s management, the domaine has gone through thick and thin in the 20th century. Family members Elie Issa and Nayla Issa el-Khoury took over the domaine from the Brun family in 2003 and continue the legacy of Domaine des Tourelles. Today, Faouzi Issa, the son of Elie Issa, is the winemaker and his sisters are in charge of the administration and marketing for the estate. They are the youngest team who run one of the oldest wineries in Lebanon.

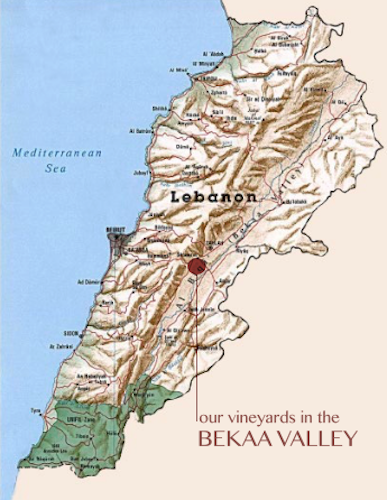

Domaine des Tourelles has almost 100 acres under vine, all organic and dry-farmed. Most of the vineyards are located in the village of Ammik, in the western side of Bekaa Valley. There are two smaller parcels located in the central Bekaa Valley, which are in the villages of Jdita and Taanayel. Vines are trained as free-standing gobelet, with some of the vines considered the oldest in the Bekaa Valley. Hand harvest is mandatory; only indigenous yeast is introduced during the winemaking process and minimal sulphur is added while bottling. Minimal intervention is essential to Faouzi Issa’s philosophy of winemaking.

Grape Collective talks with Faouzi Isaa about being the youngest winemaker in Lebanon, managing the 150-year-old estate and making the award winning Cinsault.

Joyce Lin: Would you please tell us a little bit more about yourself and your background in winemaking?

Faouzi Issa: My name is Faouzi Issa and I'm the youngest Lebanese winemaker today.  I started to produce my wines at the age of 26 in the oldest winery of Lebanon. I studied agricultural engineering at the American University of Beirut. Then I decided to learn how to make wine. I traveled to France and I studied oenology at University of Montpellier in southern France where I earned my masters degree. I worked with René Rostaing in Côte Rôtie for six months and then I worked at the famous Chateau Margaux winery in Bordeaux from 2007 to 2008. One day my father called me and said, "Hey, get back to Lebanon," and I went back to Lebanon and started to produce my own wines at the age of 26.

I started to produce my wines at the age of 26 in the oldest winery of Lebanon. I studied agricultural engineering at the American University of Beirut. Then I decided to learn how to make wine. I traveled to France and I studied oenology at University of Montpellier in southern France where I earned my masters degree. I worked with René Rostaing in Côte Rôtie for six months and then I worked at the famous Chateau Margaux winery in Bordeaux from 2007 to 2008. One day my father called me and said, "Hey, get back to Lebanon," and I went back to Lebanon and started to produce my own wines at the age of 26.

Please tell us the history of Domaine des Tourelles.

Domaine des Tourelles was established in 1868 by a French civil engineer, François-Eugène Brun. Mr Brun was in Lebanon working on the construction of the highway that was to connect Beirut (Lebanon) to Damascus (Syria). The director of the construction project was Mr. Zucker from Switzerland. In 1864, he built a stone house in the city of Chtaura, in the Bekaa Valley, which is eight kilometers (five miles) from the Syrian border. Four years later, Mr Zucker passed away and his wife decided to sell the house and return to her home country. It was at this point that François-Eugène Brun bought the house, and seeing the ideal weather in the Bekaa Valley, a valley floor that is protected by two mountain chains, he recognized the potential of the landscape for wine production. So in 1868, he started planting vines and thereby established the first commercial winery in Lebanon.

Today we are known for making prestigious wines with minimum intervention. We're also the youngest and most dynamic team who run the oldest winery today in Lebanon. Johanne, my twin sister, is the art director of the winery. She’s in charge of all the graphic design and such. Christiane, my older sister, is responsible for the administration, management and marketing for the winery and Emile, our partner, runs the communication and marketing.

So, the estate is located in Bekaa Valley and it's one of the most promising wine regions in Lebanon. How would you describe Bekaa Valley in terms of the climate and the terroir?

So if I want to be scientific, I would say the Bekaa Valley is one of best areas in the world. If I want to be poetic, I would say it's the sexiest area in the world. Bekaa Valley, in general, is 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) above sea level which you can't find anywhere in the world. It is also not an ideal place for pathogens and insects because of the dryness and low humidity, so it is suitable for organic viticulture. In addition, we have four distinct seasons in Lebanon.  Once the month of May hits Lebanon, flowers are everywhere and birds are chirping. It’s spring! Then comes the hot summer, which gives us a great maturation period for grape ripening and vegetative cycle. Another crucial factor of the terroir, getting scientific again, is the diversity of the soils we have in Bekaa Valley. You know, Bekaa Valley is a high altitude plateau trapped between two mountain chains: the Lebanon Mountains and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. The composition of the soil varies from the valley floor to the mountain top. Another reason that makes Bekaa Valley special is the rainfall. The average rainfall in Bekaa Valley is 31.5 inches. Sometimes we have the hydric stress but it is good to let the vines struggle a little bit and it’s global warming everywhere. Last but not least, while our summer days are hot, given the altitude, our evenings are quite cold, which helps the grapes maintain their natural acidity.

Once the month of May hits Lebanon, flowers are everywhere and birds are chirping. It’s spring! Then comes the hot summer, which gives us a great maturation period for grape ripening and vegetative cycle. Another crucial factor of the terroir, getting scientific again, is the diversity of the soils we have in Bekaa Valley. You know, Bekaa Valley is a high altitude plateau trapped between two mountain chains: the Lebanon Mountains and the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. The composition of the soil varies from the valley floor to the mountain top. Another reason that makes Bekaa Valley special is the rainfall. The average rainfall in Bekaa Valley is 31.5 inches. Sometimes we have the hydric stress but it is good to let the vines struggle a little bit and it’s global warming everywhere. Last but not least, while our summer days are hot, given the altitude, our evenings are quite cold, which helps the grapes maintain their natural acidity.

From my point of view, Lebanon is not Burgundy, Lebanon is not Bordeaux, Lebanon is a wine-producing country with a long history. More than 2,000 years of winemaking history since the Phoenicians and the Romans who came to Lebanon. Many civilizations passing through Lebanon have worked in the trade, in the vines and the wines. Some French asked me, “Do you have Cinsault? It is known as a French variety, but I would say, “Yes, it’s a French variety, but we brought it to Europe.” The right way to put this is the Phoenicians brought the grape to Europe. They traded with vines. It is just we didn’t have the technology to grow multiple varieties back then. But nowadays, we have some cool native crops too. So, with all these components, Bekaa Valley is truly unique and I think that’s sexy.

What is your philosophy of viticulture?

Minimal intervention in the vineyard is what we do. Because the minimum amount of spray you use on the vines, the better their immunity will be. The fewer chemical products you use, the better the wine will taste, with vital aromas. And if you create, or you raise, a good indigenous yeast, with time, you will have a consistent quality of wine. So my philosophy is minimal intervention. Let’s put it this way, if you work in Bordeaux, it's all about the weather. It is always foggy and humid, sometimes we need to treat in order to prevent fungus to grow. But in Lebanon, the philosophy is go wild, get a wild product, and that's it.

Do you do organic farming?

Oh yeah, big time. We are organic but we are not certified organic and we don't need to be certified.  Most people should understand that Lebanon is a native organic country. We don't need to be certified and pay for the certification just for the need for marketing. There is a TV channel in Lebanon who wants to pay us $10,000 to apply for the organic certification and we said no. From our point of view, there is no need for that. Consumers know Lebanon is like that. Same as Valley de Loire, lots of organic and biodynamic farming happening there.

Most people should understand that Lebanon is a native organic country. We don't need to be certified and pay for the certification just for the need for marketing. There is a TV channel in Lebanon who wants to pay us $10,000 to apply for the organic certification and we said no. From our point of view, there is no need for that. Consumers know Lebanon is like that. Same as Valley de Loire, lots of organic and biodynamic farming happening there.

When did you start to practice organic?

The Bekaa Valley is known for organic farming for a long time. I started to amplify the organic activity after I came back from France in 2008. Chateau Margaux is one of the best wineries in the world. They are not 100% organic, but they use indigenous yeast and they are doing some wild production, such as Côte-Rôtie with zero intervention. And this all gives you an idea, that if you have a healthy, great terroir, then the vineyard can do 90% of the job. You just need some confidence.

So are there a lot of vineyards practicing organic like you?

Surprisingly, only a few wineries practice organic farming because not a lot of owners are winemakers. And if you're an employed winemaker who works for the winery, you will be scared of missing one vintage, so you will over-treat and over-care for the grapes in the winemaking process. But if you're the owner and winemaker of the winery you can take as much risk as you want, because no one would kick you out if you messed up one vintage.

After two vintages using organic grapes, I realized that’s the best way to go. In addition, my bills dropped dramatically after practicing organic farming. We just buy sulfur and potato starch and that’s it. If you see the bills from other wineries and the money they spend in the vineyards, you will find their bill is a hundred times more than ours. I mean, they don’t want to risk missing any vintage.

Why do you choose to practice sustainable farming in addition to organic farming? How does it make a difference in terms of the environment and for the people who work in the estate?

We do sustainable practice in agriculture, winemaking and even behavior. Because we believe no matter what we produce it is related to the soil, to the earth, to the human beings, and to the mountains as well. We need to protect the environment; protect ourselves as a community in the area. So we opened a small wine shop in Beirut to further the sustainable idea and to communicate and educate our customers. I think we are the only winery that has a wine shop in Beirut because we don’t like our wine to be misplaced in the market.

In addition to that, we started to ask our customers to bring the wine bottles back to store so we can recycle and reuse these bottles without polluting the environment. We have a machine that can do the job in the winery.

When I say sustainable behavior, we do not replace our employees with a machines easily.  We like to protect the environment by protecting the people, the families that are working for us. We have 50 employees so far and we produce 300,000 bottles of wines along with 300,000 bottles of Arak, which is the traditional spirit of Lebanon. We're the leading producer in the Lebanese spirits market. This is the social responsibility to the community, to the history, to the surroundings.

We like to protect the environment by protecting the people, the families that are working for us. We have 50 employees so far and we produce 300,000 bottles of wines along with 300,000 bottles of Arak, which is the traditional spirit of Lebanon. We're the leading producer in the Lebanese spirits market. This is the social responsibility to the community, to the history, to the surroundings.

Another thing is we make our own compost. We use the residue of the grapes to make compost, and we spray them on the vines as organic fertilizer. We use a lot of glasses and materials to make gadgets, marketing gadgets like candle holders using our bottles. This is how we work in the winery, in the farming. At the end of the day, we are not Goldman Sachs; we are farmers and we produce agriculture products and that's it. When people visit our winery, they say, "Oh, you're manufacturing." No, it's not manufacturing. We're not a factory. We're a winery. This is the sustainable behavior in keeping all the families working for us.

Please talk a little about your philosophy of winemaking. Has your winemaking method changed over time?

I made a few changes when I started to work in the winery in 2008. I kept the original concrete vats that are 150 years old, but employed a new marketing team when I took charge of the estate. You know, it could be risky for a well-established winery to be run by a young winemaker who just got out of school and is put in charge of everything. I think I was very lucky that I had good training in some of the prestigious wineries. These wineries are great models and examples. They inspired me that we can sell high-quality wine without doing any technological intervention. Thanks to my father, he lets me take charge of the winery with full trust, otherwise we will never know the consequences.

Tell us about working with René Rostaing and in Chateau Margaux.

I remember the first day I arrived at Domaine Rostaing, a man opened the door and I said, “I’m your new employee from Lebanon.” He said, “Yeah, please come in. Who do you want to meet?” I said, “Mr. Rostaing, the owner.” He said, “Can you please wait there?” So I waited and the guy started to swipe the floor, move the hoses and do all the cleaning. After he was done with the work, he came over and said, “I’m René Rostaing.” So he is the owner of the estate and he does everything himself. I was 25 at the time and I realized that you have to be hands-on even if you are the owner. You need to work and get your hands dirty. Then I worked at Chateau Margaux, snobbish area, Margaux and everything, but the winemaking process is wild there. I mean, wild yeast, dusty and dirty winery but the product is amazing and fabulous. I learned so much and gained lots of experience while working at Margaux.

When I came back home, I told my father, “Listen, I need to get my hands dirty and work. I’m not going to sit behind the desk and I need to be crazy in winemaking, so don’t worry about the 150-year-old concrete vats getting dirty. Let them be dirty because there are dirty tanks in the premium chateau in Bordeaux and they are selling their wine at $2,000 per bottle.

The training I got from working with these producers gave me confidence and I believe I can produce wine the way I want without following a recipe. One day I’ll follow my instinct and produce wine that I’m proud of.

With that said, I produce a 100% Cinsault wine and it’s very rare in Lebanon. French winemakers in Lebanon think Cinsault is only for rosé. How come this Faouzi is doing 100% Cinsault? He’s gonna fail. Yeah, I was out of stock in less than a month when the wine hit the market.

Wow… That was a triumph! Would you consider Cinsault to be the next superstar in Lebanon?

Oh yeah, without any doubt. I would say the Cinsault I produced in the 2014 vintage made the Lebanese winemakers think twice about Cinsault. If you google 100% Cinsault, you will find Domaine des Tourelles popping up. Because we created a revolution by making 100% Cinsault in Lebanon. Even Jancis Robinson picked 2014 Vieilles Vignes as the wine of the week on her website in 2017. We take our Vieilles Vignes and participate in lots of wine competitions either in Lebanon or internationally. In these competitions, we were against Cinsault from all over the world, like South Africa, Chile, Argentina and the South of France. Our Cinsault was one of the best among all of the competitors. How our wine differentiates from the others is the altitude and the terroir of Bekaa Valley.

That must mean a lot to you! So, tell us about the grapes you work with and the wines you are making.

So we have international grape varieties which are Syrah, Cabernet, Cinsault and Carignan. In my opinion, Cinsault is an adopted grape in Lebanon. Since the French don’t like it anymore, we adopted it. We take good care of it. I would say, Cinsault now is more Lebanese than French.

So we have international grape varieties which are Syrah, Cabernet, Cinsault and Carignan. In my opinion, Cinsault is an adopted grape in Lebanon. Since the French don’t like it anymore, we adopted it. We take good care of it. I would say, Cinsault now is more Lebanese than French.

The white grapes we work with are Viognier, Chardonnay, Obeidi and Muscat d’ Alexandrie. Obeidi is a native grape. We produce rosé too, and that is a blend of Tempranillo, Cinsault, and Syrah. Then we have Arak, a traditional spirit in the Middle East. Arak is distilled from wine and fresh anise seed is added during the distillation process. It is typically served broken down with water, which turns the spirits a milky white color.

It's true that most of the grapes are international varieties, but growing these international grapes like Syrah, Cinsault, Carignan in 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) high above sea level in Lebanon, the fruits taste so different and the terroir gives different aspects of these international varieties. You will find the earthiness, the minerality and the beautiful Mediterranean background of the wines. I think it's very identical to the area.

How many bottles do you produce a year?

In total we produce 300,000 bottles of wine and 300,000 bottles of Arak. So 600,000 bottles in total.

What is your biggest export market around the world?

Today, our number one export market is Europe, especially in England cause we’re represented everywhere in Europe. We think the United States would be the next. We only do business with family-owned importers or distributors. We never go with the big ones. In New York, it’s Victor Schwartz with VOS. In the UK, It’s Boutinot, also a family-owned business, and we work with Balsam in Norway. We need family business owners to understand our family spirit and wine production.

Lastly, why do you think people should drink more Lebanese wine and how would you describe your wine to those people who are not familiar with them?

Lastly, why do you think people should drink more Lebanese wine and how would you describe your wine to those people who are not familiar with them?

So, the wines of Lebanon have a long historical background. In the Bible, Jesus turned water to wine in House of Lebanon. Bacchus is the Roman wine god and the temple of Bacchus, which was built by Phoenicians thousands of years ago, is in the Bekaa Valley. Controversially, people think Lebanon is a 100% Muslim country and wonder how we can produce wine. You know, the fact is Lebanon is a multi-religion country, we can make wine and drink alcohol freely here. Even Muslims in Lebanon, they drink more wine than Christians. We know in Ramadan period (the holy month of fasting for Muslims) the alcohol consumption drops but after it ends, they drink more wine than ever. We have the history, the religious, the political quality, the small production. We produce 9 million bottles in Lebanon. Can you believe it? But it’s like nothing, a small city in the States can buy them all. I think people should try something new. They need to go back to the roots where wine was made before.

*Photos courtesy Domaine des Tourelles

For more on Lebanese wine, check out:

Our interview with Sami Ghosn of Massaya

Our interview with Marc Hochar of Chateau Hochar