If Kevin Morrisey hadn’t jettisoned his career as a cinematographer after shooting “Headless Body in Topless Bar” and "Killer Tomatoes Eat France,” he might have a genuine, heartfelt Oscar contender on his hands with his current endeavor as winemaker and general manager of Ehlers Estate near St. Helena. There’s everything here: love, sacrifice, wine, war, death and an enduring legacy of caring about others.

Here’s the core of it: French citizens Jean Leducq and his wife, Sylviane, who lived long lives, used the wealth from the family’s international linen company to fund research into cardiovascular diseases, which claimed Jean’s father and grandfather and is a major cause of deaths worldwide.

The vehicle for this, the Paris-based, not-for-profit Leducq Foundation, also owns Ehlers Estate, a 42-acre historic wine estate that channels all of its proceeds into the foundation. A byproduct of this virtuous cycle, if you will, is a lineup of seven beautifully crafted, intensely fruited, elegant wines that John and I have enjoyed for decades. I raved about the 2014 Ehlers Estate Sylviane Cabernet Franc Rosé ($28; the 2015 is sold out) and its sur lie Sauvignon Blanc ($28) a couple of years ago.

If ever a winemaker and a winery were destined for each other…

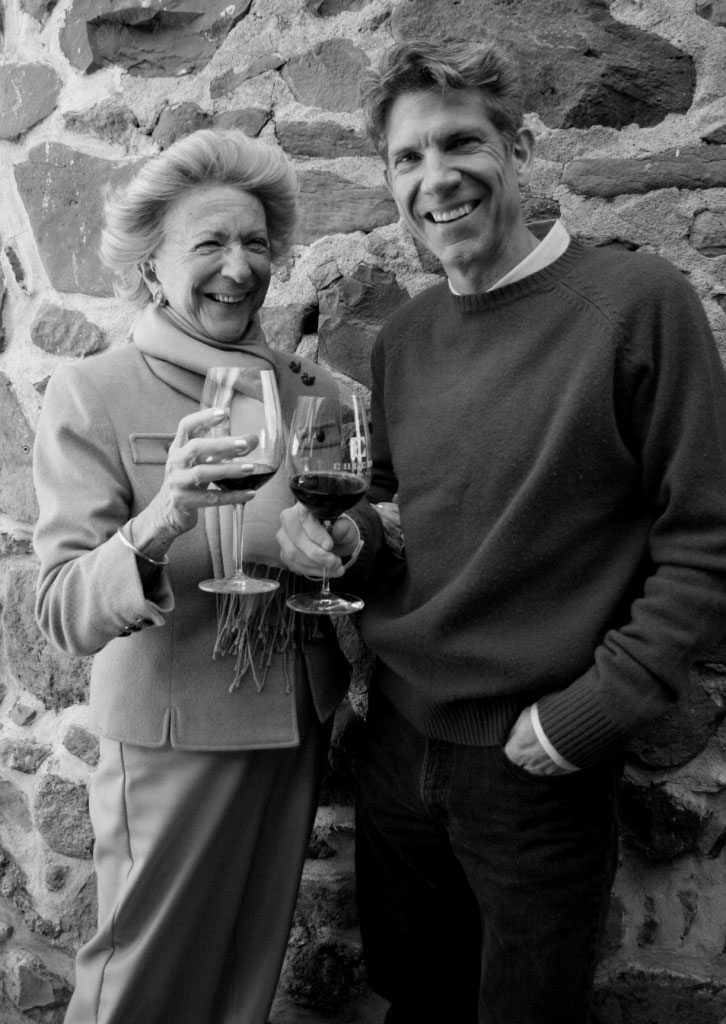

(Photo: Kevin Morrisey with Sylviane Leducq)

“I make the kind of wines I like to drink,” said Morrisey, 56, who joined Ehlers Estate in 2009. He was in town recently with some of his current releases, all from certified organic, estate-grown fruit. He produces 10,000 cases annually, most of it sold through the winery’s mailing list and to restaurants. Tall, lean and wry, Morrisey has dual French-American citizenship. He and his French-German actress wife, Karin, have two daughters, all world travelers, as he was, growing up with a special affinity for France. He’s from Philadelphia. The Leducqs, lovers of fine food and wine, especially Bordeaux, planted Bordeaux varieties.

“My palate is international. I hung out with a lot of Europeans. They are my references,” Morrisey explained.

After his masters degree in filmmaking led to 10 years making movies and television shows and the work eventually dried up, he succumbed to the pull of wine, which had been intensifying for years with trips to Napa with friends. So at the age of 35, Morrisey got a masters degree in enology from UC-Davis. He pestered the folks at Petrus so much that they hired him as an intern. From there, he worked at Etude Wines and was working as head winemaker and general manager at Stags’ Leap Winery when a headhunter approached him about Ehlers Estate. (Stags’ Leap Winery is not to be confused with Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, whose founder, Warren Winiarski, I profiled last year.)

Morrisey said he had admired Ehlers’ Cabernet fruit for a long time but was happy at Stags’ Leap Winery. Still, the offer was irresistible. “They’re handing you a winery,” Morrisey recalled the headhunter saying. “It is ideal,” Morrisey says now. “We’re the real deal. For me to go to work and believe in what I’m doing, that’s ideal.”

What’s especially ideal, he said, was the Leducqs’ embrace of organic and biodynamic principles, working in a way that’s safer for vineyard workers, the land, the vines—practices he had been passionate about for years. The 42 loamy acres, which get early fog that burns off to full sun that’s followed by cool breezes, are divided into five main plots based on soil type and 25 subplots organized by soil, varietal, rootstock and clone types. Morrisey and longtime vineyard manager Francisco Vega are aided by eight full-time, year-round employees, “who have the same benefits as I do,” Morrisey said.

Since Jean died at the age of 83 in 2002 after 58 years of marriage, and Sylviane, who was awarded the French Legion of Honor, died in 2013, I wondered to whom Morrisey answered. The finance officer of the foundation, he told me, adding that that gentleman had no interest in being hands-on and that the trust “wasn’t looking for short-term gains and doing things like requiring 10% more each year.

“That frees me up immensely. I’m not chasing trends,” he explained. “I’m refining and polishing a long-term vision: to make the best wines we can make using the best practices.” Although Ehlers Estate is owned by a not-for-profit, “I have to be profitable,” Morrisey said. “You have to pay your bills.”

The history of Ehlers Estate and the Leducq family is an interesting one. In 1885, Bernard Ehlers, a Sacramento grocer who sold shovels, picks and other tools to gold prospectors, used his fortune to relocate his family to Napa’s Lodi district. There he purchased and resurrected a dying vineyard and planted olive trees that still bear fruit. In 1886, he finished building a stone barn winery, which serves today as the tasting room. After he died, his wife sold it and it at one point, during Prohibition, it was owned by bootleggers.

Also in 1886, Théophile Leducq, Jean’s grandfather, hit on a great business idea: laundering and renting tablecloths and napkins to restaurants, Morrisey told me. As Martin Landaluce, president of the foundation, told the St. Helena Star two years ago, Théophile “also noticed that some businesses didn’t mind a few stains on their tablecloths. So Théophile rented the newest linens to fine restaurants, and as they aged he’d rent them to cafes and the like, eventually renting the most-used items to the city of Paris for use in their public restrooms.”

In 1945, soon after Jean and Sylviane got married and almost immediately after World War II ended, Théophile sent Jean to a check out one of the family’s factories that had suffered damage during the war. Their business had also suffered because materials they depended on had been diverted to the war effort. In the city of Rouen, Jean saw the U.S. Army packing up to evacuate, “leaving piles of camouflage canvases behind,” Landaluce told the St. Helena Star. “So he struck a deal with the U.S. Army for the discarded canvases, bleached them out and used the material to supply his customers,” rescuing the family business.

In the early 1980s, the company, having expanded throughout Europe, bought a plant in Virginia. Jean, Morrisey said, was “a wine geek,” and he and Sylviane, inspired by Thomas Jefferson’s example, founded Prince Michel winery in Madison, Virginia, planting the Bordeaux varieties they loved.

After failing to make the wines they wanted to, Morrisey said, they listened to an adviser who told them they needed to grow grapes in California. So in 1987, they purchased choice vineyard land on what was by then called Ehlers Lane, employing Jacques Boissenot, a French enologist, to help them lay out their vineyards. For a few years, they flew their California grapes to Virginia, Morrisey told me, in time deciding, wisely, to make wine from Napa grapes in Napa. Their first release, a Cabernet Sauvignon, came in 2000. In 2001, they bought the stone barn and released their flagship wine, 1886 Cabernet Sauvignon, in honor of the stone barn winery’s completion in 1886.

The current range, the reds are all 2013, includes three Cabernet Sauvignon: the regular Estate Cabernet Sauvignon, $55; J. Leducq Cabernet Sauvignon, $75, which is from a single vineyard; and 1886 Cabernet Sauvignon, $110, built to last decades. There’s also a Merlot, $55, a Cabernet Franc, $60, and a Petit Verdot, $60.

I tasted the following with Morrisey: The 2015 Sauvignon Blanc from a single vineyard was rich with honeysuckle and orange blossoms on the nose, minerals, mango and passion fruit and nice weight, and what he called “ripping acidity.” His reference: Sancerre. “This is a labor of love,” he said, sipping it. “No oak, no malo. Bone-dry. Never grassy or green pepper. Always floral and tropical fruit,” he added. Made me smile.

The Merlot came from two different blocks of fruit and had 5% Cabernet Franc in it “for spice,” he said. It’s a Merlot for Cabernet lovers and I loved it. Deep, dark-berry fruits, with a serious clarity about it.

I’m partial to Cabernet Franc and this was a fabulous one. Spicy and elegant. Beautifully structured.

The 1886 Cabernet Sauvignon came from the highest part of the property and it was intense and powerful. It could have walked to the table, yet it had great finesse.

John and I knew nothing of the history of Ehlers Estate when we visited its stone barn tasting room many years ago and bought a wine with the name Leducq on the label. The last vintage of that wine was 1989, Morrisey said.

What’s more, he told me that he had met us in 2000 when The Wall Street Journal’s Weekend Edition hosted an Open That Bottle Night celebration for vintners in Napa. He was at Stags’ Leap Winery then. Small world. (Remember, OTBN is the last Saturday in February!)

These wines were a terrific reminder of all of the history in the bottles we open, and of the people who make them possible.

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.

Read more columns by Dorothy J. Gaiter on Grape Collective.

As of publication Elhers Cabernet and Sauvignon Blanc are available at Cellar d'Or in NY for $26 and $50.