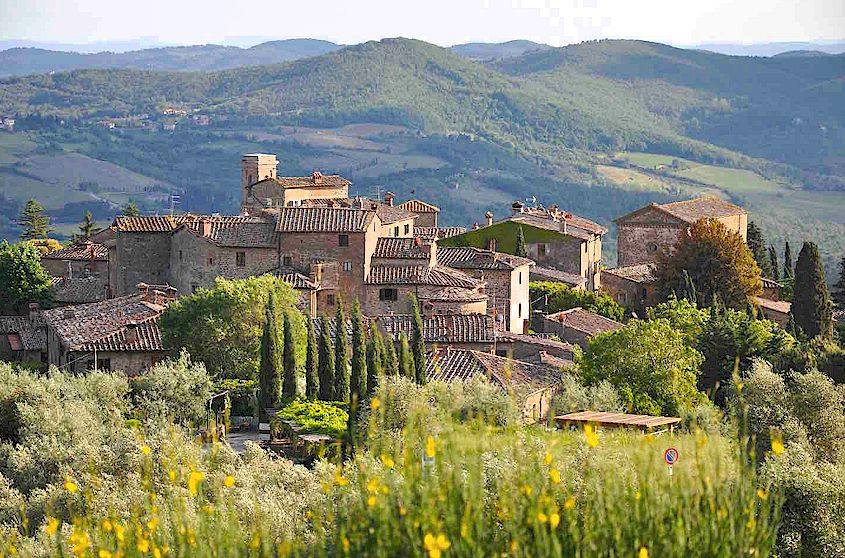

Castello di Volpaia produces Chianti Classico of great elegance. This is due in part to the extremely high elevation of the vineyards as well as the thoughful organic, non-interventionist winemaking practices. Volpaia is one of the highest-elevation wineries in the Chianti area at 1,300 to 2,130 feet. The winery sits at the top of a stunning 11th century fortified village on the Florenc-Siena border. Nearly the entire village is intimately involved in the production of wine and olive oil.

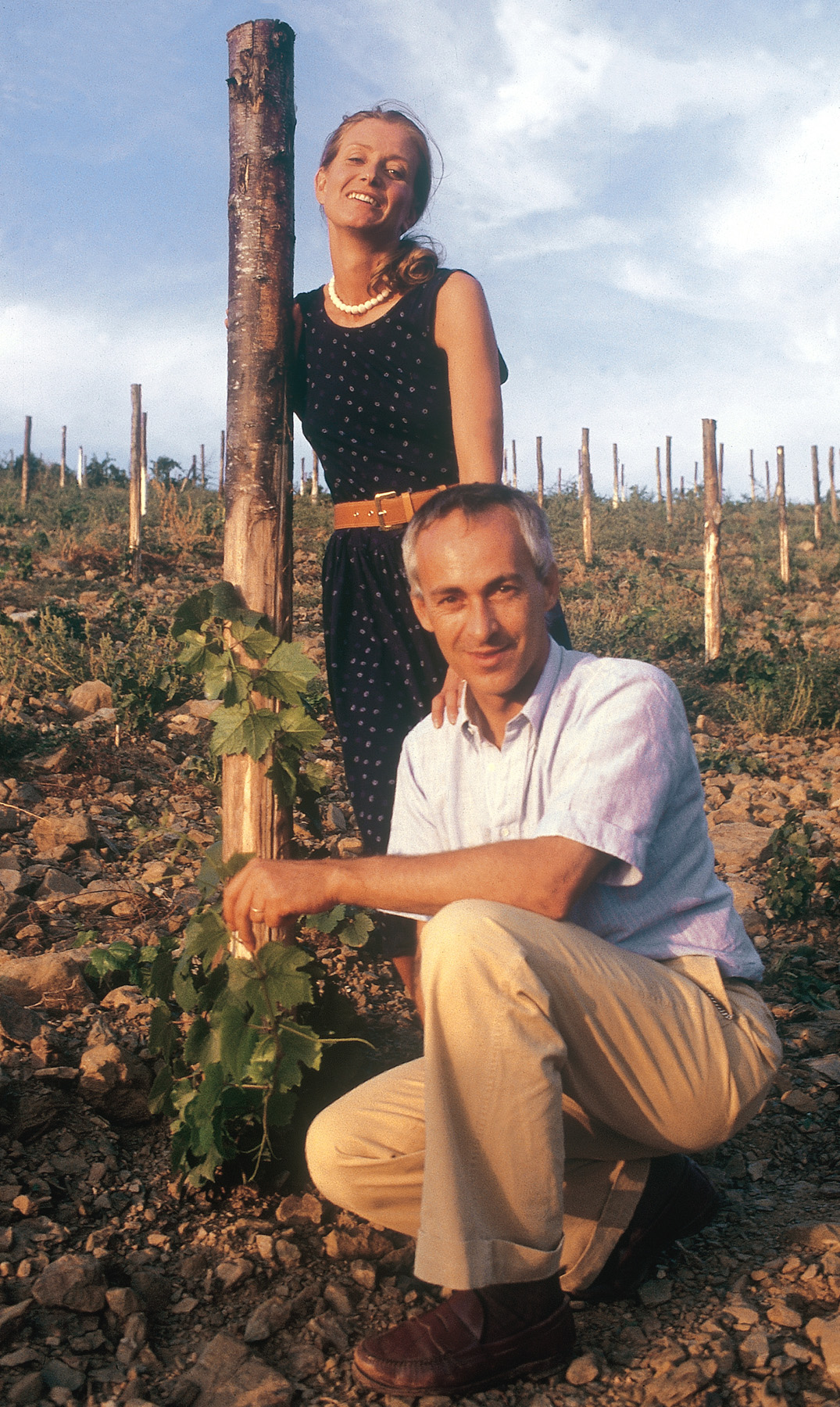

Raffaello Stianti, one of Italy's top printers and bookbinders, purchased the estate in 1966 and gifted it to his daughter Giovannella and her husband Carlo Mascheroni in 1972 as a wedding gift. “Volpaia” means “fox’s lair” in Italian. Today, the Stianti Mascheroni family owns close to two-thirds of the village including 114 acres of vineyards and 40 acres of olive trees.

Monty Waldin talks to their daughter Federica Mascheroni Stianti about their strong commitment to organic viticulture and the beauty of high altitude Chianti Classico.

Federica Mascheroni Stianti photographed by Monty Waldin

Monty Waldin: Hello Federica Mascheroni Stianti from Castello di Volpaia. Let's talk about Chianti, Chianti Classico. Can you give us a little background of your family history, of this very famous estate.

Federica Mascheroni Stianti: Everything started with my grandfather. It was in 1966 when we took the first step. Then actually, the paperwork took two years, we are in Italy! The real date is 1968. Then the first vintage in this cellar was in 1968. That was when we started. It was much more for fun. It was even more fun when my grandfather gave Volpaia to my mother as a wedding present. She was marrying a man from Milano. You know Milano and Firenze at that time were very far away.

Milano and Firenze, there was no quick railway line or ...

No, it was not easy to travel by train or by car so it was quite complicated. She said, "Why are you giving me a present like this? I will never be able to go there." She didn't realize that her new husband and my grandfather were becoming very close friends, and they started to create a lot of ideas for Volpaia. My mother started to get involved in this big project that is Volpaia. Then she really became really the big boss of Volpaia. Now, she is the one.

In the beginning, she was the one, with my father, who travelled every weekend, back and forth because we were young, and she had to be in Milano with us children. Now, she lives mostly here. Unfortunately, for her, with me now! We live, both, most of the time here in Volpaia, especially during the summer there are many more crazy and busy moments.

In the middle of the 1960s, Chianti was not a world-famous wine by any means was it?

No, no.

How hard was it for your family? Were they initially just making wine as a hobby, just for home consumption? Or was there a big plan that one day they would be conquering world markets?

No, no plans. As I said, it was a passion. It was loving the lifestyle, loving drinking. We are from Tuscany, you know. We have to sit down, have a meal in front of us and a glass of wine, a good [olive] oil, and some bread. And that's it, we are happy. Everything began for pleasure. My grandfather came here for hunting, for the reserve, and obviously with friends you need a glass of wine. It was for that reason!

What did he hunt, because you're surrounded by forest?

Pheasant.

What about wild boar?

No, no, he was much more focused on pheasant. He had a reserve. Then the government removed the license for the reserve, so we couldn't go to the reserve.

A reserve, right?

Yeah, reserve. I don't know if it's the same in England or other places.

Basically he saw this as a hunting lodge?

Yes.

A place to make a little bit of wine, grow a few vegetables, and ...

And enjoy life.

Live the dream.

Yes.

Thirty, forty years on, perhaps you could say that your father and grandfather were kind of traditionist Chianti producers. Have you seen changes, like the modernization of Chianti? What are the positive and negative sides?

I think that it's not really that we have been modernizing. A lot of people come and think that, generally speaking, making wine is making money, easily, and in a nice way. Nobody understands how much work is involved. I think now more and more people understand that to make a bottle of wine is not the same as making a can of something else.

The people who come from a long wine tradition are still working the same way. For people that are just starting, they are probably working in a bit of a different way, thinking and putting a lot of effort inside, is everything easy, everything easy; and then they realize, okay, so to replant a vineyard takes seven years. Okay, so it means that to make something ... everything is slowly by slowly.

Also, for us, probably the big change is only technology. Actually, in the end when we talk about it, aging is the same as it was in the past, for Chianti Classico and Chianti Classico Riserva.

You mentioned technology in wine making. Has that been a good thing for Chianti Classico? Has it been a negative? Or is it a little bit 50/50? In technology, we're talking about like maybe new oak barrels from France, giving the wine an oaky taste; the introduction of French grape varieties like Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon from Bordeaux to kind of make the wines a little bit more “sexy," if you like.

It's much more fashionable I think, than sexy. The idea is probably to try to sell as much wine as possible. Again, this is more of a point of view, to sell, instead of making the wine for pleasure. Yes, I don't really agree with the people who add too much international grape, or too much wood. It's always a balance. Its like the recipe of the Chianti Classico, you know it has changed year by year; and now you are even allowed to have 100% Sangiovese, that wasn't allowed before. The climate and the palate of people changed.

Years ago if a plumber came to your home in the early morning, it was normal to offer a glass of wine. The wine had to be very light and very easy to drink, not too complicated. Everybody, at the end of the lunch time, workers, were drinking a glass of wine. Now, if you see somebody drink a glass of wine during working hours - it's totally not allowed. The alcohol level in the bottle of wine is totally different.

I think palates have changed, fashion has changed, people have changed; so something also has to change in the wine. And the climate, we cannot change that one. It's something that changed, and so we have to follow that one.

How are you reacting to climate change then?

For us, I think it is something good, this climate change. We like it from one point of view. The altitude of Volpaia is 600 meters, 1,800 feet high elevation. It means that usually we miss a little bit of sun. With this change in climate, it helps us a little bit more with the ripeness of the grape.

At the same time, it's totally crazy. Outside, now it's winter, two weeks ago it was like summer. I thought we were in spring. Rain and sun and humidity, it's very dangerous when you're an organic grower; so for us, it's always a big challenge. We’ve been organic for a really long time.

When we talk about Classic Chianti, which a very fresh red wine, not overly alcoholic, a good wine with food, how did it suddenly became a very dark, overripe monster for a few years ... Was that the fault of journalists favoring these big wines?

Definitely.

Or was it the producers who created that trend?

Unfortunately, it's very rare that you have a producer that doesn't listen to journalists, because the consumers listen to the journalists. If the journalist wants a Bordeaux in a Chianti Classico, you have to change your style a bit, even if you don't want to.

Even if we wanted to, we don't have really very much more room to move around, because of the altitude, the micro-climate of Volpaia, and the soil which is quite unique. We are much more into elegance, than in body of the wine. You can definitely recognize the wine in a blind tasting, but it's never a fashion wine; even if we wished it. We cannot really reach that fashion section.

One of the issues that consumers have, is that there are so many different kinds of Chianti. There's Chianti, Chianti Classico, Chianti from Florence, from Siena, etc. What is your view on that? Consumers understanding the different between Chianti and Chianti Classico?

I think most of the producers, not everyone, from Chianti Classico made a big mistake when the Consortium thought ... They were a bit too proud about their personality, their wines. They thought they could give this word "Chianti" to these other sectors out of the Chianti area. This created, all over around the world, a big confusion between Chianti and Chianti Classico.

What is the difference between the two then?

It's like talking about Brunello, Chianti, and Chianti Classico; they are three different appellations. All three are different. I cannot say that my Chianti Classico is a Brunello, and at the same time a Chianti cannot say that its Chianti is a Chianti Classico, and vice versa. The problem is to communicate to the public the difference. When you have the same word, and a very famous word, as in Chianti; it's very complicated. In the future, I think our focus should be to let the people understand the difference, and to educate them. Let them try the wines, and explain why one is two Euros on the shelf, and a wine with a similar name is 12 Euros on the shelf.

Generally, the Chianti would be low-priced and Chianti Classico would be a bit more expensive?

That is really general, because there are Chianti with high quality, higher priced, definitely yes. Even in the Chianti Classico, you can find really cheap wine. When you have the two wines in the glass, you understand why one is cheap and why one is not cheap. Again, you have to explain this to the consumer.

Chianti Classico comes basically from the best land between Florence and Siena? And Chianti can come from a wide area, outside that area?

Yes, to both.

From your perspective, what are the three things that make a good Chianti Classico?

A lot of love, work ...

In terms of somebody tasting it. Is it because the tannins are much smoother? The wine is more complex?

Compared to a Chianti?

Yes. More concentration? More depth? More interest?

Often, a Chianti Classico could be much smoother, a bit bigger in the style. Consider, for example, the quantity of grape per hectare [permitted grape yields] in the Chianti Classico is much lower than the quantity of grape per hectare in the Chianti area.

Its low yield, so ...

Yeah. It means that you have one plant concentrated on two bunch and the other one is one plant concentrated on three bunch of grapes. It's different.

It's basically one vine is producing less bottles of wine in Chianti Classico, than in Chianti; which means that the Chianti is less concentrated and maybe less interesting in flavor.

It's difficult really to do such a broad generalization, because I think sometimes you can even have a Chianti Classico Riserva that tastes like a Brunello. It's so variable. It's about the quality of the producer. That makes a huge difference. It's not only about the area where you come from.

What you're saying is it's not just the ingredients, it's the chef as well that's important.

Yes, it's both.

If somebody said, maybe one idea could be that Chianti Classico should only be made from traditional Tuscan grapes, whereas Chianti could be made from Bordeaux grapes and French grapes as well as local Tuscan and other Italian grapes ... Would that be maybe a good start to really return to tradition?

It's difficult. For example, even for us, we put some international grapes inside a Chianti Classico. Not on the Riserva, but on the Chianti Classico.

Like Merlot, Cabernet ...?

We put only around, even less than 10% of Merlot. This helps us because of the elevation of Volpaia. If we don't put some Merlot, our Chianti Classico cannot be ready in one year to be on the market. We need something that smooths, elevates the wine, otherwise it would be too rustic for the palate of the people that would drink it.

I agree to put international, 10% of Cabernet Sauvignon, for me, would be too strong; but 10% of Merlot, grown in this area, is okay for me. It makes a good balance inside the wine. Before we were putting even 5% of Syrah, but it was really too much. It was giving too much pepper, too much taste of something different; so we stopped doing it.

Our focus is to concentrate on Sangiovese. In the past, it wasn't the only grape that had to be in the Chianti Classico. But now, we are concentrating on Sangiovese, so Riserva, Coltassala, Il Puro; all these three concentrate on Sangiovese. The only one, is the Chianti Classico and we put a touch of Merlot.

One of the trends in Chianti, which is a very welcome one from my perspective, is that there are a lot of organic growers. You're one. How important is “organics” for tourists. Do they want to see lots of flowers in vineyards and bees buzzing around, or do they not really care about this eco movement?

Actually, it's the opposite. When they come and stay in the apartment, they say, "Oh, we have too many bees around here." I mean, this is something good, it's not something bad. Come on! The normal tourist doesn't really understand what it means. Tourists comment about the swallows that fly around. "Oh, it's so terrible. They're so dirty." Yes, but this is something really good, because they were disappearing and now they are back. This is really important, but the tourists really do not seem to understand.

Then, talking about the bottle, when they look at the bottle, "Ahh, it's organic!" They are excited. I think, on the organic side, you have more or less the same confusion as the Chianti and the Chianti Classico. An organic, you start to talk about natural, then you go to biodynamic, then you talk about ... "I'm organic, but I'm not writing on the label, is because, because ..." Because it's too complicated to do it.

I agree with you about that. I think it's important that if you say you're organic that you should be certified, for sure.

Yes.

In terms of your terroir, you are at quite a high altitude. What about the importance of the hill slopes and the soil type that you have here? What influences do they have on the taste of your wine?

It's a huge influence. The soil of Volpaia that you find here, you can also find in Arbole, in Lamole, and in many other places here in Chianti Classico. It's mainly a stone called il Macigno del Chianti, really from Chianti. It's a bit darker, compared to all the other stones that you find around. If you walk around the village, you can see how dark it is, because you see all the palazzos on the buildings are quite darker. It's a sandstone. When you work the soil with this stone, it became sand.

It's quite a loose soil, so the roots can go really deeply down in the soil. This means that they can get the water from really deep down, 4 or 5 meters down. It means that you get a nice minerality. You will have elegance in the wine. You will never have a body builder wine in our area; it's not possible for us. It's rare to have very high in alcohol, because usually the ripeness is quite following the altitude. Only in a very hot season like 2012, 2003, can you find high alcohol. Yes, it's a big influence in the wine.

Obviously, this area between Florence and Siena is one of the world's major tourist attractions, with two historic cities. How do you deal with all the tourism, in terms of the waste and the pollution, and that kind of thing? How easy is it to deal with that?

It's always a nightmare. We have tried to explain to the tourists, for example, park the car outside the village and come in, walk around. It's a nice village to walk around. Obviously, they start to park in the front of the door. One car on top of the other one. It's a tiny village. What do you want? We started to put flowers everywhere, only to survive from all these people. At the same time, we are so tiny that we cannot have a bus service that comes to us; so unfortunately, everybody that wants to come to us can come biking, or with a car.

We have always tried to conserve the environment of Volpaia, so that we don't have a ghost village, like a museum. So everything is inside all the buildings. It's much more difficult for us, but it's much nicer for the people that come and for the life of the village. You see all these wonderful places in Italy, totally abandoned; and here, because of this, because of the restaurant, because of this nice place, you have a lot of people that come and keep life inside the village. That's important!

Do you think that tourists want to see that? The fact that the villagers are working, living villages with people working in the fields, working in the vineyards, working in the olive groves. Do you think they appreciate that?

I don't know if they always understand, because not everybody can see these things; but sometimes they say, "That was so fantastic. It was an atmosphere that was different." But they cannot explain the atmosphere. It’s because everybody is doing something. It’s not a lonely place, a silence in the middle of nothing. It is a place with life. If you give life to a place, the visitors who come can feel it, and get it. That's my idea about it.

I know you have like a second career working in the art world, shall we say. You seem to be someone that's quite happy in a very isolated, hilltop, medieval town, rather than a big, busy city like Milan, like your ancestors, Is that true?

Yes. It depends on the people that come here. Some want the silence. They leave here and say, "It's amazing, fantastic." Other people comment, "It was a place without anything. I mean, I had the connection to the wifi, but the phone worked only next to the window. It was difficult." Yes, that’s the way it is. Come here and relax, not type all the day and stay on Facebook, Twitter, or things like that. It's one second to enjoy the landscape and the life, instead of being in a crowded city.

It's funny, because my family comes from Milano, so friends from Milano come here and when you see them in the morning and say, "What happened, didn't you sleep?" They respond, “It was too silent, I couldn't sleep." The silence was too difficult for them.

The buildings we're in at the moment, the Volpaia, it's called a Borgo. First of all, what is a Borgo?

A Borgo is like a village, we say. Especially this one, is a fortified village.

It's strategically based on a hill. How old is it and what is the history of Volpaia?

Obviously, like everything all over the world, it was not built in one day. The first document that mentions Volpaia was in 1172. Everything started at that moment, so it was really a long time ago. For example, some buildings were built much later, like in the 14th or 15th century, some even later. It was a step by step process of the different buildings, and the reconstruction of the different buildings, year by year.

We're kind of midway between Florence and Siena. Was Volpaia a Florentine, on the Florence team, or was it on the Siena team, or was it its own team?

It tried to be on its own, but obviously it wasn't possible. With or against Florence and Siena, a bit with one, and a bit the other one. Now, geographically speaking, only for a few kilometers is under Sienese people, and my mother is from Florence. For her, she still thinks, “It’s only few kilometers away, so why don't you put the border here instead of there? Put it inside Volpaia."

Is there still a rivalry between villages? What are your neighboring villages? Was there a rivalry about I live in the best village, the most beautiful village? We make the best wine here, rather than you. Or was it a little bit more relaxed?

In Tuscany, I never heard the word “relaxed.” I never heard about not fighting one village with another one. Luckily, my mother raised my brother and I in Milano and then we moved here. I felt a bit out of all of this. I still feel sometimes, like almost scared, until about five years ago, people from Florence would ask me, "Where did you study at high school?" "I studied in Milan." "Oh, so you didn't do Michelangelo, Dante, that they were all the high school of the city of Firenze." I said, "No, I didn't." So they cannot classify you. They cannot put you in this box, or that one. I say, "No, I'm a foreign person.”

Do you think that is reflected in your wine, though? You're not making a Siena-style Chianti Classico or a Florence-style Chianti Classico? Could you say that?

I don't know. I can see a lot of my mother in my wine. I know this. I can definitely read my mother inside the bottle of wine. I think she is part of the wine, so yes, more my mother than Milano, Siena, or wherever. Her personality is inside.

(Carlo and Giovanella Stianti Mascheroni)

What is the personality in there, then?

Ahh, she's so elegant.

If your mum sees this, it's okay. You pass the test.

Yes, I think, its elegant, but with a strong personality. Definitely, yes. It's a wine that you love or you don't; it's not really a middle of the road wine. You like it or not, that's it. Yes or no. Black or white.

How have your wines evolved? We're sitting in a cellar here with some older wines. How the wines evolved over time? Do you have a philosophy of wine making?

I will give you the same answer that I received when I was in France. The wine have a life, it goes up and goes down. If you like it, you pick the bottle in the moment that its up; but if you don't like it, you picked the bottle when its down. It's not the right answer that I want to hear, but it's more or less like this. We often do wine tastings and we always comment, "Why is it that this one last year was excellent, and now it's not as good as the other one?"

Obviously, you're quite a high vineyard and quite a cool vineyard, but you've got this kind of warm soil. When is the best time to drink Volpaia? Is it after one year, is it after five years, after ten years?

In a Chianti Classico, after two years, more or less. It depends on the vintage. The 2012 vintage was warm, especially at the end of the vintage, probably a Chianti Classico, even after one year, was perfect. A 2010 Chianti Classico, I would say probably after two years. On the Riserva, it's the same concept. It depends on the vintage. Again, for example, 2012 was really was very fruity. It was very easy drinking. For me, 2013 now is a bit too young, and I think it needs a little bit more time to get up and to show all its flavor.

Plus what is important in my wine and in most of the wines, is that it is very difficult when I'm in Vinitaly, for example, and people taste it and say, "Okay, yes." Then they move on to a second one. It's the time that the wine has to stay in the glass. It's not a wine that shows everything in one shot. It's not like the modern wines from South Africa or California that you pour in a glass, and you have that wine.

It is a wine that you feel -I don't know- blueberry. After a while, you feel blackberry. After a while, you feel the violet. It's step by step, and you discover more and more. It's from my contemplation of the wine, but it's difficult. All the time, you taste and you drink, and you do everything too fast. It's our generation, and I don't really appreciate that.

Doesn't that make Chianti Classico such a fantastic wine with food?

Yes.

Also in Italy, you do tend to eat a lot; but you're all very slim because you eat healthily, and you take you time over food. And these wines deserve a little bit of time in the glass.

Yes, this is what I appreciate, because you can drink the wine slowly during lunch or dinner; and so appreciate all the flavors and the changes in the wine.

How do you see the changes in Chianti Classico from when your father and grandfather were making wine? They were small scale producers in the early years when they were out hunting, and now you export your wines all over the world. How do you view the changes that have occurred?

The wines have changed a lot, because of the weather, because of the change of the recipe of the wine. This represents a huge change inside the bottle.

What about the techniques, not just the grape varieties; it's always been a Sangiovese based wine. Some people have put French grapes in, which they are allowed to do; but what about some of the techniques that you can do during the wine making that have made the wines different from say 20, 30, 40 years ago?

I can give you a rough answer. The techniques have changed. For example, before everybody was punching down the grapes and trying to extract as much as possible from the skin, from the seeds; so punch down, punch down during the fermentation. Now, everything is much softer. Everything is much more, if you will, pulling the wine from the bottom, shower on top softly [pumping the still fermenting wine from the bottom and showering it over the red grapeskins which have floated to the top of the tank in order to get the red color and flavour into the wine.] Everything is done much more softly, and this time has to be done much longer time. All the techniques have totally changed.

It's a little bit more delicate now, isn't it?

From what I remember, I think so. My memory doesn't go back very far, because before I was only drinking, but not really thinking. I was appreciating and trying the different wines too see the difference, but not really going into the cellar and try to understand how it was before.

On the aging side, I think it hasn't been a big change. The big change occurred around the end of the '70s. The Barrique from France came, and so that was a huge change in winemaking. Most of the producers put a lot of Barrique everywhere.

Copying Bordeaux.

Copying Bordeaux, but fortunately everybody reduced more and more, the Barrique presence in the flavor of the wine.

Chianti Classico was flirting with France a few years ago, now it's coming back to it's roots.

I think so, yes.

What do you think is an ideal food that would go with your Chianti Classico?

With a Chianti Classico, simple pastas or even at lunch time, a glass of wine, and then go on. At the same time, if you go to Livorno, you have a wonderful Cacciucco, a fish dish with tomato that’s fantastic. It doesn't have to be too light food, but simple food, everyday; and you can go on without any problem. Obviously, I would not suggest a fish on the grill with a touch of oil and my Chianti Classico; I would suggest to you much more a Vermentino. You need a little bit of sauce on what you will eat after.

Monty Waldin was the first wine writer to specialize in green issues. He is the author of multiple books, including The Organic Wine Guide (Thorsons, 1999); Biodynamic Wines (Mitchell Beazley, 2004); Wines of South America (Mitchell Beazley, 2003), winner of America’s prestigious James Beard Book Award; Discovering Wine Country: Bordeaux (2005) and Discovering Wine Country: Tuscany (2006), both Mitchell Beazley; and Château Monty (Portico, 2008). Monty has contributed on topics of organic and Biodynamic wine to Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine Guide, Tom Stevenson’s Wine Report and he wrote the entries for Biodynamics and organics in The Oxford Companion to Wine (2015; 2006). He has also contributed to BBC radio and TV, numerous British newspapers and websites, as well as to wine, travel and environmental publications including Decanter, World of Fine Wine, The Ecologist, Star & Furrow (journal of the Biodynamic Agricultural Association, UK) and Biodynamics (journal of the Biodynamic Farming & Gardening Association, USA). His most recent books are Monty Waldin’s Best Biodynamic Wines (Floris, 2013) for wine drinkers, Biodynamic Gardening (Dorling Kindersley, 2014) for biodynamic home gardeners, and Biodynamic Wine (2016, Infinite Ideas Oxford), the comprehensive how-to guide for biodynamic wine-growers and students of biodynamic wine.

Buy Monty Waldin's detailed guide to the nuts-and-bolts of biodynamic wine-growing on Amazon.