The Y-Burg, a small, curiously named fortress ruin, crowns a prominent hill in Württemberg’s Rems River valley.  Just below the structure, a wild garden clings to the slope. In spring and summer, it is overrun and intensely fragrant with herbs, flowers, grasses, and bearing fruit trees, the whole of it girded by rambling drywalls. This little Eden is, in fact, one of visionary winemaker Jochen Beurer’s vineyards. Its rampant abundance of flora at first belies the plot’s purpose, which comes into clearer focus only when you learn its name: Rettet die Reben (“Save the Vines”).

Just below the structure, a wild garden clings to the slope. In spring and summer, it is overrun and intensely fragrant with herbs, flowers, grasses, and bearing fruit trees, the whole of it girded by rambling drywalls. This little Eden is, in fact, one of visionary winemaker Jochen Beurer’s vineyards. Its rampant abundance of flora at first belies the plot’s purpose, which comes into clearer focus only when you learn its name: Rettet die Reben (“Save the Vines”).

(Jochen Beurer. Photo credit: Emily Campeau)

Beurer, 46, is best known for his pure and intense dry Rieslings and a handful of reds, all farmed biodynamically, spontaneously fermented, and remarkably terroir expressive. He is also a champion of historic grape varieties, many of which have nearly vanished from this corner of southwest Germany. With as little as a vine or two of some varieties, this splendid Wengert, as the locals call a vineyard, puts preservation into living context. (And into an ur-traditional Gemischter Satz, or field blend.) “We are always looking to work against monoculture in the vineyard,” says Beurer; bringing so many species into coexistence “makes the vineyard lovely, complete.” Beurer considers his vineyards places "where you can go before work and just stay there, look around, and feel. That, for me, is the very important thing, to go in a vineyard and feel what's going on there. And every time you are there, you are absolutely excited about the future.”

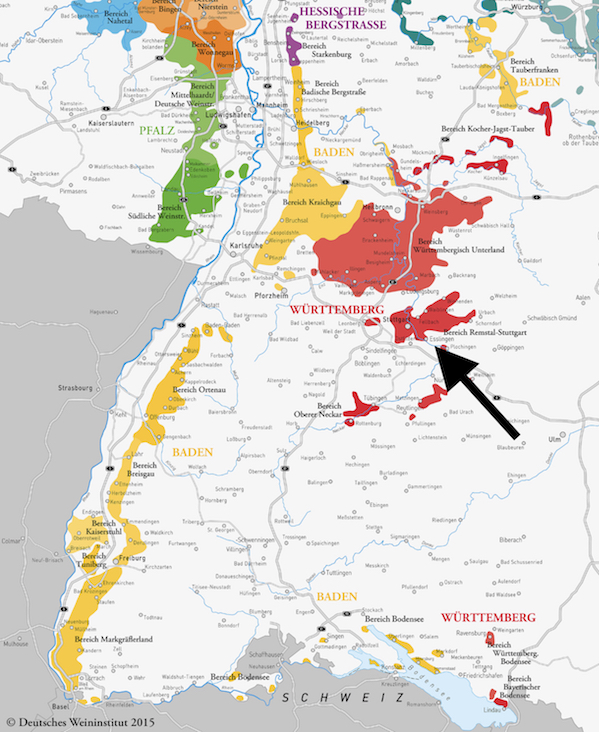

Until quite recently, “excitement” and “wines of Württemberg” were two terms rarely conjoined in the same sentence.  Despite being the fourth-largest wine producing region in Germany, it has long been marginalized — derided for its culture of hobby winegrowers, abundance of cooperatives, and lowest-common-denominator winemaking. When critics have thought of Württemberg at all, most have done so only to deride it as the “Trollinger Republik,” in reference to thin, sweetish red wines that were long happily drunk by the liter throughout the region. Even as one of the most acclaimed winemakers in Germany, Beurer encounters disdain: “When I go to Hamburg,” Beurer says, “I ask people to taste my wine. They say, ‘Oh, I don't need wine from Württemberg.’ That’s real.”

Despite being the fourth-largest wine producing region in Germany, it has long been marginalized — derided for its culture of hobby winegrowers, abundance of cooperatives, and lowest-common-denominator winemaking. When critics have thought of Württemberg at all, most have done so only to deride it as the “Trollinger Republik,” in reference to thin, sweetish red wines that were long happily drunk by the liter throughout the region. Even as one of the most acclaimed winemakers in Germany, Beurer encounters disdain: “When I go to Hamburg,” Beurer says, “I ask people to taste my wine. They say, ‘Oh, I don't need wine from Württemberg.’ That’s real.”

(Rettet die Reben. Photo credit: Edition Randgruppe)

But all this is changing. Fast. If there’s a single catalyst, Beurer may be it. He’s smart, funny, totally down-to-earth. He’s also an independent thinker with a healthy disregard for complacency. Over the 20-plus years he’s been making wine, he has never wavered in his belief that Württemberg, and the Remstal in particular, is a force “not just for Riesling, but for everything.” Suddenly, it seems his faith has been vindicated. The once sleepy area around the prosperous city of Stuttgart feels wide awake. Inspired by Beurer’s lead, a fresh crop of homegrown talents are building local pride over outside prejudice — working close to nature with complete confidence in their terroirs and varieties.

Among these younger producers, Olympia Samara and Johannes Hoffman, of the tiny upstart Weingut Roterfaden in Rosswag, credit Beurer with inspiring them as “the first in the region to work biodynamically and to ferment all his wines naturally. He believes in that and in leaving his white grapes on the skins, sometimes for weeks, although people around him criticized him as ‘the freak.’ He always thought in a different way and probably therefore especially his Rieslings were a revolution in our region.” Moritz Haidle, third-generation winemaker in Stetten at Weingut Karl Haidle, sees Beurer as “the one who is exploring the most. It was he and [Fellbach-based producer] Rainer Schnaitmann who brought Württemberg out of Germany.”

To understand Württemberg’s wine culture past and present, we need to go back to 1552. That year, agricultural inheritance laws took effect, giving an equal share of a family’s assets to each heir. The multitude of minute vineyard holdings (even now the average parcel size is just 0.6 hectares, or 1.2 acres) and the cooperative nature of winemaking that characterize the region to this day are a direct legacy of this. Moreover, as historian Dr. Christine Krämer has noted, Württemberg was long sited “at a cultural crossroads” — between Burgundy and Jura to the west and Bavaria and Austria to the east — open, from the very beginning, “to assimilating varieties, planting methods, vinification styles, and habits of consumption from other regions.”

To understand Württemberg’s wine culture past and present, we need to go back to 1552. That year, agricultural inheritance laws took effect, giving an equal share of a family’s assets to each heir. The multitude of minute vineyard holdings (even now the average parcel size is just 0.6 hectares, or 1.2 acres) and the cooperative nature of winemaking that characterize the region to this day are a direct legacy of this. Moreover, as historian Dr. Christine Krämer has noted, Württemberg was long sited “at a cultural crossroads” — between Burgundy and Jura to the west and Bavaria and Austria to the east — open, from the very beginning, “to assimilating varieties, planting methods, vinification styles, and habits of consumption from other regions.”

(Putting Württemberg on the map. Image credit: Deutsches Weininstitut)

Over time, Württemberg developed an enduring association with one grape and one style of wine: Trollinger — a transalpine migrant from South Tyrol — better known as Schiava. In times of war and privation, of which Württemberg has seen plenty, Trollinger was a reliably generous bearer. For this reason, it was planted, willy nilly, on grand cru sites and flat fields. Per capita, Wuerttemberg has the highest wine consumption in Germany, and coops have long met the undiscerning demand, commonly using mash heating methods, which tended to make wines Beurer dismisses as “strawberry jam.” To go against this style was to transgress the habits of inconspicuousness and thrift for which Schwaben — Swabians, in English, as the people of Württemberg refer to themselves — are famed. Beurer has never cared about that. (And, for the record Beurer makes a Trollinger, too. His drinks like a bluebird day in the mountains.)

The Beurer family has farmed in Stetten for generations. Growing up, Jochen’s father, Siegfried, led a local coop. Beurer says he always knew he would follow his father into winemaking. But there was another passion he had to follow first: BMX biking. This took him all the way to the title of European champion, cementing his cool kid reputation.  That accomplished, he returned to wine, apprenticing in Württemberg and nearby Baden, working in the cellar of a large coop, studying at Weinsberg, Württemberg’s top oenological school (and Germany’s first, established a dozen years before better-known Geisenheim). From there, Beurer headed to Trentino, in northern Italy, to stage with natural wine icon Elisabetta Foradori. “That was the point where I was fresh from studying a lot of technical and chemical stuff. I went there and really learned what it means to work by hand. It made a big impression.”

That accomplished, he returned to wine, apprenticing in Württemberg and nearby Baden, working in the cellar of a large coop, studying at Weinsberg, Württemberg’s top oenological school (and Germany’s first, established a dozen years before better-known Geisenheim). From there, Beurer headed to Trentino, in northern Italy, to stage with natural wine icon Elisabetta Foradori. “That was the point where I was fresh from studying a lot of technical and chemical stuff. I went there and really learned what it means to work by hand. It made a big impression.”

(Cellar view. Photo credit: Emily Campeau)

Around that time, Beurer’s father was becoming disenchanted by the large-scale practices of the cooperative. “He wanted to turn it into its own small, outstanding coop,” Jochen says. “We wanted to improve the quality of the wines by finding the joy in them.” Coop members didn’t share this vision. “It wasn’t an easy decision for us to leave. But the day after members decided against it, we said, ‘OK, we will start Weingut Beurer.’”

This was 1997. “We were working conventionally then. But there was one tank I fermented with native yeasts. And I liked the taste. So I did more and more. By 2003, the whole winery was using native yeasts. That was the time to say, ‘OK, we are spraying the vineyards against fungus and we ferment with native yeast. We have to change.” Four years later, Weingut Beurer went biodynamic and in 2012 the winery was certified by the rigorous global organization, Demeter.

In 2001, Beurer and four forward-thinking winemaker friends from various parts of Württemberg banded together to form Junges Schwaben, the name a reference to their local identity and youthful ambition. “We started just because we wanted to go to ProWein together,” Beurer explains, referring to the world’s largest wine trade fair, held annually in Düsseldorf. “It’s cheaper to make your own stand and it's more powerful when you are five wineries. In 2001, it wasn’t normal to exchange information with other winemakers. But we worked as a group and we traded our thinking, our information, tasted our wines together.” From the outset, their objective was to bring an avant garde approach to local tradition and share their vision of what Württemberg wine could be. “It’s really, really nice to see what's been going on between 2001 and now. This is the kind of work that is pushing the region forward.”

In 2013, Beurer was invited to join the VDP, a selective association of German wine producers that doesn’t exactly have a reputation for high-fiving mavericks. Beurer’s inclusion is an indication of the seriousness of his wines, grown on sites classified as 1er Lage (premier cru) and Grosses Gewächs (grand cru). He knows precisely what he wants from them: “purity, minerality, vitality, tension, complexity, expression” — and gets it. But what takes these wines to another level is a quality the Germans rather untranslatably call Trinkfreudigkeit (being joyful to drink).

He achieves this, above all, through what he calls “great sensitivity for the right moment in the vineyard.” Where others might eagerly act and shape, Beurer watches and waits. “I’m always looking for ripe-colored leaves, ripe seeds, good fruit and aromatics. We prune with the waning moon. At harvest, we look for the rising moon phase, to give us a little more power in the grapes. I think we can bring all the power from the grape, the soil, the vineyard into the wine when we respect what’s going on in the vineyard, the situation with the sun and the climate, and so on. We’re just adjusting ‘nature’s screws,’” Beurer avows.

He puts great stock in the herbal concoctions biodynamic practitioners refer to as teas: “We make horsetail tea in the spring, for silica. We use nettle tea and also willow, because it's like aspirin. Always when there is pressure from fungus — peronospora, for example. You spray the willow, it reduces inflammation. Also, we use camomile tea as a disinfectant. When there is too much pressure from the peronospora, it's like a small disinfectant. We use baking powder to strengthen the leaves and it's also good against fungus.”

Improbably, Beurer’s biodynamic toolkit also includes his bike. “I’ve done my biodynamic preparations, my 500 or 501, on my BMX quad. People were a little confused. They saw me with a quad in the vineyard. They didn’t understand that,” he says, blue eyes twinkling. “But my tractor is three tons and the quad is only 240 kilograms. So it’s easier to work with it there, it’s gentler, it’s better for the soil. Why not?”

Improbably, Beurer’s biodynamic toolkit also includes his bike. “I’ve done my biodynamic preparations, my 500 or 501, on my BMX quad. People were a little confused. They saw me with a quad in the vineyard. They didn’t understand that,” he says, blue eyes twinkling. “But my tractor is three tons and the quad is only 240 kilograms. So it’s easier to work with it there, it’s gentler, it’s better for the soil. Why not?”

(Riesling renegade. Photo credit: Emily Campeau)

However, if Beurer’s farming philosophy can be reduced to a single key element, it is biodiversity. Several years ago, Beuer learned that an abandoned parcel in the famed Pulvermächer vineyard was available. Inspired by a lecture on the history of medieval grape varieties in Württemberg, Beurer launched a search for these vanished old vines to plant in the vacant parcel that became Rettet die Reben. Beurer explains that his search for historic vine material has benefitted from “a sort of automization: somebody reads about the project and says, ‘Hey, I know a guy who does all that’ or ‘Check that old variety there,’ and then I ring up: ‘Can I get some vines from there?’ There is a guy from the government and he's absolutely a fan of this project and he has contact to northern Italy, to South Tyrol. And then he has contacts there, there, and there, and he is always bringing me new varieties.”

As a result, Rettet die Reben now harbors grapes from A to, well, at least R: Adelfränkisch (at home in Germany for more than a 1,000 years), Affenthaler, and Ahorntrauben through to Roter Gutedel and Roter Urban. “We are looking more for grapes that are from our area, but we also plant other stuff that is typical of where it’s from. Now there are more than 25 varieties there. They are thriving among peach, almond, and quince trees, a mix of herbs, and old drywalls, just as they used to earlier. We have birdhouses and an insect hotel. For me, it's just a perfect showing of the biodiversity you can do in a vineyard.”

It's also a savvy investment in the future. As climate change demands greater adaptability from all species, these historic varieties may point the way forward for winegrowers throughout Württemberg and beyond. “These truly old varieties have experienced warm periods as well as a 300-year-long little ice age,” Beurer has written. “They’ve survived every kind of climate craziness and ecological change, which makes them extremely interesting for Württemberg now.”

Eighty percent of wine production overall in Württemberg is red, with Trollinger, Lemberger (aka Blaufränkisch), and Pinot Noir dominating. Stetten has always been a bit different. “Since generations,” says Beurer, “when you read all the books about wine farming in the 18th or 19th century, Stetten always had more white wine.” Accordingly, more than half of Beurer’s vines are Riesling. The cool side valleys, steady ventilation, expositions that avoid direct southern sun, and elevations ranging as high as 400 meters (1,200 feet) above sea level are ideal for the quintessential cool climate grape.

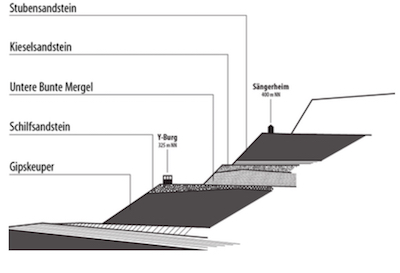

Bodagfährtle, Swabian dialect for terroir, evokes not just soils and climate, but a feeling for them as well.  Across his 10 hectares (25 acres), Beurer is acutely attuned to his particular set of soils and elevations. Layers of gypsum, clay, colored marls and a range of sandstones translate into compact, structured, deeply mineral wines. (Stetten soil structure. Graphic credit: Weingut Beurer)

Across his 10 hectares (25 acres), Beurer is acutely attuned to his particular set of soils and elevations. Layers of gypsum, clay, colored marls and a range of sandstones translate into compact, structured, deeply mineral wines. (Stetten soil structure. Graphic credit: Weingut Beurer)

Stetten is home to two particularly notable Riesling vineyards: the tiny Brotwasser (a monopole belonging to another producer) and the vast Pulvermächer. The latter encompasses 38 hectares (94 acres) of what were once myriad terraced parcels. But in the 1950s and ‘60s, the very topography and soil structure of the Pulvermächer, along with countless other vineyards throughout Germany, were altered by a government program of vineyard reorganization, or Flurbereinigung — truly the F word of German viticulture. Beurer’s parcel of the Pulvermächer is on Kieselsandstein (pebbled sandstone), with vines replanted shortly after the restructuring. With extended skin contact and ten months in 500-liter neutral wood cask this wine gives what Beurer calls “the austere, powerful precision of a linear Bach invention, where every element has a role and a reason. Another parcel, on Schilfsandstein (reed sandstone) has a higher iron content and “the roots have to fight a bit more for their nutrients, for the minerals,” Beurer explains. These wines are distinguished by power and body at very low alcohol levels (typically 11.%5 abv).”

The site that seems closest to Beurer heart is a steep, high 1er Lage parcel Beurer calls Junges Schwaben. He's watched it evolve from a place so cold it could only give "sour, unripe wine" to " one of the most interesting parcels." It's a prime example of the paradoxical benefit of climate change for German wine growers. "You have forest at the top and this always pulls down the cool air. You can harvest these parcels three weeks later than the others. That’s perfect for me because I always harvest very, very late. Early harvesting is a big problem, I think, for the future. The Burgundy problem — premox — I think it will come to Germany also because at the moment there is a lot of early harvesting.”

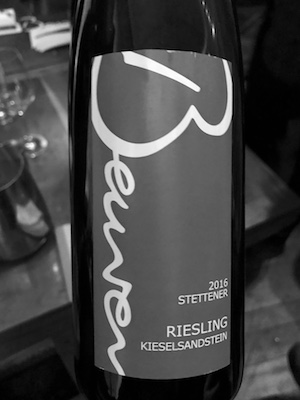

But with Beurer you don’t necessarily need to scale the ranks of the classified sites to experience greatness. His Stettener Kieselsandstein, from another high elevation parcel with 35-year-old vines and deliberately low yields, made with long lees contact, gives a Riesling of mountain stream clarity. Beurer says the site is “a little bit more slow ripening so you get a little bit more fruit and more extract, also, in this wine.” When we open a bottle together, he pauses to consider the wine at this particular moment: “I like the taste today because it's really, really crispy and very salty.”

But with Beurer you don’t necessarily need to scale the ranks of the classified sites to experience greatness. His Stettener Kieselsandstein, from another high elevation parcel with 35-year-old vines and deliberately low yields, made with long lees contact, gives a Riesling of mountain stream clarity. Beurer says the site is “a little bit more slow ripening so you get a little bit more fruit and more extract, also, in this wine.” When we open a bottle together, he pauses to consider the wine at this particular moment: “I like the taste today because it's really, really crispy and very salty.”

(Trinkfreudigkeit. Photo credit: Author)

Among Beurer's Ortsweine, or village-level bottlings, a true standout is the Austrian crossing, Zweigelt. Grown on Bunter Mergel (colored marls) it becomes smoky, streaky, electric, defining what Beurer is all about: taking wines to an edge without ever losing balance or control. His approach to achieving this is what he calls “Kontrolliertes Nichtstun” -- controlled idleness. Crucially, he gives his wines time. All ferments are spontaneous, some taking close to two years. He accepts malo in his Rieslings if that is what nature wants. He is moving away from filtering (“I think it’s the future”). He has shifted the rhythm of botting “so the wines can stay longer in tanks or barrels. Before we always had to bottle the wine in front of harvesting. That was always stressful for the wine so now we have a little more space.” Beurer encourages drinkers to take a similarly relaxed approach to experiencing the wines. Use a big glass, let the wine unspool. When we tasted together, circumstances were somewhat rushed. “I hate that,” Beurer says flatly.

Beurer and his wife, Marion, have three children. “Last year my oldest son, Adrian, finished school and opened pop-up wine bar in the neighboring village. It was very successful and we had a lot of fun.” He notices that “it’s becoming more and more common to see little groups like Junges Schwaben. Here a small group, there a small group.” He pauses. “When you look at Württemberg, it's actually huge. And we are just in this small part here, in the Remstal. There are a lot of young producers here and they have a lot of energy. They all think about organics now. In Stetten alone we have nearly 35% organic. I see the Remstal as the center of Württemberg at the moment, the place where this energy and power is coming from. We do our own style. That's, for us, so necessary. I don't like it when somebody comes and says, 'You have to do that like this and it has to taste like that.' In the future, maybe we can having our own region. ‘OK, we are Remstal.’”

This is the first in a multi-part series charting the rise of Württemberg wines.

Very special thanks to Emily Campeau for allowing the use of her photos from a recent visit to Jochen Beurer to accompany this article.