There must be something magical about the former goat farm and apple orchard in the Napa Valley that Frederick Hoyt McCrea named Stony Hill. When he and his wife, Eleanor Wheeler McCrea, were looking for a place outside San Francisco where their family could enjoy nature in the 1940s, during World War II, that land on a northeast slope of Spring Mountain captured their imaginations and wouldn’t let go.

Thank goodness for that. The high-elevation, dry-farmed Chardonnay they planted in 1948 and began bottling in 1952 has been called one of the first California cult wines. Lean, bright, vividly acidic and minerally, with elegance, complexity and balance that get better with age, it remains to this day true to their vision. Hugh Johnson, in his 1989 book “Vintage: The Story of Wine,” wrote that “a dozen California winemakers were feeling their way towards quality in the late ’40s and early ’50s.” Among them, he said, was Stony Hill, “an estate that was to become a miniature jewel, a secret first growth for white wines.”

If you’re not familiar with it, it’s because in an industry where showy, expensive things often trump substantive elegance, Stony Hill hasn’t until recently worked hard to get attention among the general wine-drinking public. There hasn’t really been much need. Not only was it the first boutique winery established in Napa after Prohibition, the McCreas say, but it also was among the first wineries, maybe the first, to sell through a mailing list. Today, about 70 percent of its 4,000-case sustainably grown production, which now includes Cabernet Sauvignon, finds a home that way. The rest goes to choice restaurants and retailers, with older vintages available at auctions from time to time. (Skurnik.com is its distributor in the New York tri-state area.)

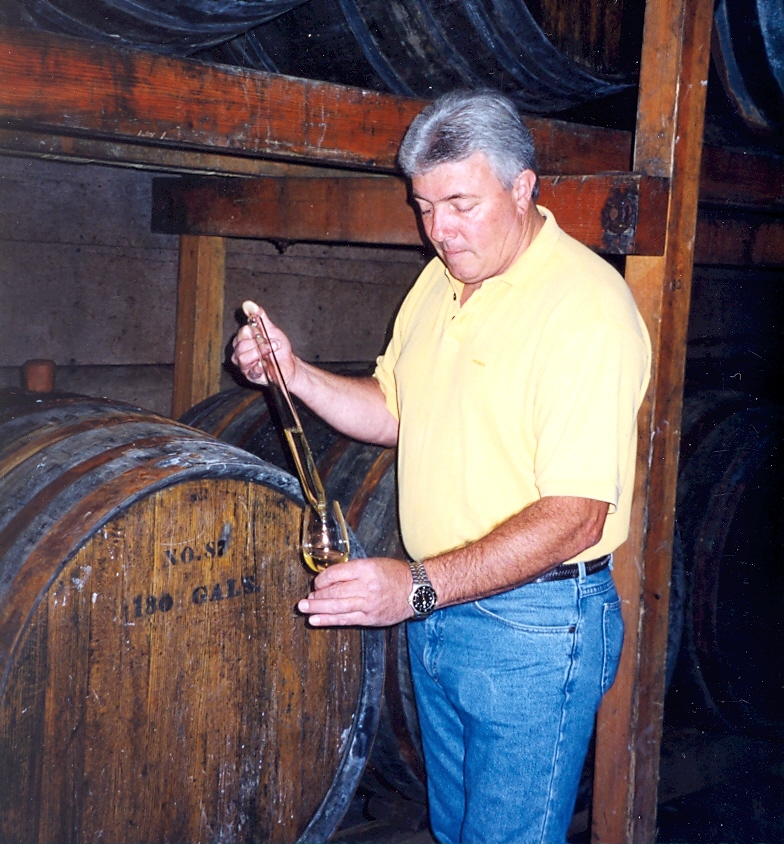

Stony Hill’s Chardonnays, some from Wente budwood, are still a serious score and an awesome deal at around $45. That’s because the family has hewed to the course Fred and Eleanor (above left) set. You want buttery, oaky Chardonnay? Look elsewhere. Perhaps more important, they’ve kept on as winemaker Mike Chelini (below right), 68, who learned old school, minimalist winemaking from Fred and made his first Chardonnay there in 1973. Chelini told me recently he is the longest-tenured winemaker in Napa Valley.

Chelini started at Stony Hill in 1972, first managing the vineyard, which reaches from, which reaches from 800 to 1,550 feet in elevation between St. Helena and Calistoga and enjoys mild temperatures. Since Fred’s death in 1977, Chelini has been the only winemaker Stony Hill has ever had. After Eleanor died in 1991, the McCreas’ son Peter and his wife, Willinda, asked Chelini to stay on. Their daughter, Sarah, who for decades was a successful brand strategist for Starbucks and other companies, became the winery’s president in 2011, while their son, Frederick, serves on its board. Alex, a cousin, tends the tasting room.

Chelini started at Stony Hill in 1972, first managing the vineyard, which reaches from, which reaches from 800 to 1,550 feet in elevation between St. Helena and Calistoga and enjoys mild temperatures. Since Fred’s death in 1977, Chelini has been the only winemaker Stony Hill has ever had. After Eleanor died in 1991, the McCreas’ son Peter and his wife, Willinda, asked Chelini to stay on. Their daughter, Sarah, who for decades was a successful brand strategist for Starbucks and other companies, became the winery’s president in 2011, while their son, Frederick, serves on its board. Alex, a cousin, tends the tasting room.

Chelini chose to stay put, at home. Since 1972, he and his wife, Kathy, have lived on the Stony Hill ranch. They raised their three children there, in the very same house the McCreas had first occupied. Chelini's son is now a consulting winemaker, a daughter is a Buehler winery sales representative, and a second daughter is a teacher in a local school.

“I really liked Fred a lot,” Chelini told me recently when I called him. “From my original hard work and dedication, he thought I was as good as it gets. Then I worked with Eleanor from ’77 to ’89 until she became ill. So no way I was leaving.”

I pressed him some more. “Of course, at one point, I wanted my own thing, but I was loyal to them. Because of them I sent all my kids to college,” he explained. “I couldn’t afford to start my own winery and part of my contract said that I couldn’t do something on the side. I still live here on the ranch. It is paradise. I never want to leave. It’s a good life.”

Others feel embraced by the place, too. Stony Hill’s six full-time, year-round vineyard employees come from three families in the town of El Llano, in Michoacán, Mexico. Alejandro Salomon, currently vineyard foreman, came in 1982. The latest was born and educated in California. Stony Hill’s website proudly welcomes visitors with appointments ($45 each) to a place “that the McCrea, Chelini, Salomon, Ayala, Rodrigues and Cortez families have called home for more than 60 years.”

In addition to Chardonnay, Stony Hill makes White Riesling, Gewürztraminer, and Sémillon de Soleil, a tiny-production dessert wine that sells out immediately. Breaking with tradition, but sticking to Fred and Eleanor’s penchant for experimentation, the winery released its first Cabernet Sauvignon in 2009. The winery sent us Cabernets, from 2009 to 2012. The 2009: “Smells like wine used to. Lovely grapey, leather nose. Soft with lovely tannins and a little eucalyptus. You go to it. Not a lot of layers now but lots of charm and elegance.” 2010: “Very different, with lots of acidity and herbs, more structure and lots of green olives, slightly chewy.” 2011: “Very fetching, with pure fruit-elegance. A tad hint of vanilla but good acidity, green olives.” 2012: “Bigger, darker, with lots of lemony acidity and weight. Not a lot of fruit. Big but still elegant.”

Fred, who worked more than 30 years as an executive with the McCann-Erickson advertising agency, and Eleanor, a Wellesley College grad who was a legal secretary, met through a mutual friend. Their courtship involved drives to Napa. After they married and had two kids they began looking for a country house, a place their gas rationing coupons could get them to easily. They gravitated back to Napa. Fred originally balked at the price of the 1890s-era goat ranch, $7,500 for 160 acres with a house, a barn, several other buildings, and a pasture. He told Eleanor that maybe they should try again after the war, Eleanor said in her Wine Spectator oral history series interview at UC-Berkeley in 1990. “He was just so morose afterward that he had given up living here that I finally said, ‘That’s absolutely ridiculous; you know we have the money.’” He listened to her, smart man that he was.

When Fred turned 65 in 1962, he retired and the family moved to Stony Hill full time, into a house they’d built, not far from a small stone winery they had constructed in 1951. Their son, Peter, and Fred’s two nephews, who lived with them, helped with the work.

Because they loved white Burgundy, the McCreas wanted to plant only Chardonnay in the rich volcanic and limestone soil. However, back then, there were only 225 acres of Chardonnay in California, so the folks from UC-Davis urged them to diversify. The Soil Conservation Department laid out the vineyards, Eleanor said. The goal was to sell the grapes.

Some Riesling grapes went to Lee Stewart, who owned Château Souverain. When Brother Timothy balked at paying their price, they stopped selling to Christian Brothers and sold their Chardonnay grapes instead to Joe Heitz, a good friend, Eleanor told the interviewer.

In time, they realized that the money was in making wine, not growing grapes, so they studied winemaking. They also got help from Louis Martini Sr., Herman Wente, Stewart, Heitz and other winemakers, who were intrigued by their little operation, Eleanor said.

“Well, when you live in the middle of a whole bunch of people who talk about wine all the time [laughs], and you drink a lot of it, you naturally get interested in it. Then after while, nobody could have made a better Riesling than Lee Stewart did, but you begin to think that it would be fun to see if you couldn’t make it that good,” Eleanor said in the interview.

“After we saw what happened to our grapes -- not at Lee’s, and not at Joe Heitz’s, but when you sold it to Christian Brothers or to Charles Krug, they just dumped all the white grapes in together. It sort of hurt your pride that your babies weren’t being treated with a little more respect, so you began to think that maybe you could do it yourself,” she added.

Of the famous Chardonnay, she said, “We didn’t really try to make it like white Burgundy; we just tried to make the best wine we could out of our own grapes. We weren’t trying to imitate anything. It turned out to taste quite a lot like Corton-Charlemagne, but that was incidental.”

“Their goal was to make wine that tasted like grapes and the place they were grown,” Sarah McCrea, who was in town recently, said of her grandparents. “They favored elegance over power.” Her visit was a good reminder that Stony Hill is still keeping the faith, still proudly without a lot of fancy equipment, but not stuck in the past. It’s ready to be discovered by a new generation of wine lovers.

“We’re realists. We understand that it’s an incredibly competitive marketplace,” she has often said. “As lovely as our family story is, as picturesque as our mountain vineyards are, and as special as visitors feel when they come and taste in the same spot where my grandmother hosted adventurers and critics alike over 60 years ago, what really matters is what happens in the bottle and in the glass year after year.”

The first harvest of Chardonnay came in 1952 and all of it went to friends and family. By two years later, all of it went to their mailing list, which started, Eleanor said, after they served their wines to friends. Those friends would ask if they could buy some; then they’d serve it to their friends. Fred also wrote letters, inviting friends to buy it. We had our first Stony Hill Chardonnay in the 1970s and bottles are still rare enough that when we come across one in a store we break out in our happy dance.

“Stony Hill has done many things for all of us,” the late Jack Davies, who with his wife, Jamie, founded Schramsberg in Calistoga in1965, said in the introduction to Eleanor’s interview. Jamie Davies died in 2008.

“Eleanor and Fred proved that lovely Chardonnay could be made in Napa. They helped prove that consumers would pay a fair price for a fine, personally made wine. They proved that one didn’t need every bell and whistle in the world to accomplish things. They proved that one could maintain personal integrity, enjoy life, and keep the checkbook balanced all at once,” Davies said. “They proved that innovation and experimentation are open for everyone.”

The Chardonnay that Stony Hill makes, half of its total production, is for people who are willing to come to it. If you wanted instant gratification, and, hey, there’s nothing wrong with that, you’d enjoy it upon release, always two or three years after the vintage. The 2013, for instance, was a complete joy. However, after a few more years, it grows in intensity with just the right amount of earthiness, minerality and acidity, altogether reminiscent, I think, of a fine Chablis with an endless finish.

This is accomplished, Chelini said, by not subjecting the juice to malolactic fermentation, which results in a creamy, buttery taste and mouthfeel. He also uses neutral oak so that you taste the grapes with their green apple-pear profile and minerals from the stony soil and not the tropical-pineapple-butterscotch-oaky profile that young oak can lend. Stony Hill’s method is hard because there’s no way to hide faults. I enjoy both types when done well.

Maintaining natural acidity is critical in the making of age-worthy wines, Chelini said he learned from Fred and Ric Forman, who gave Chelini his first job out of viticulture school, in 1970 when Forman was winemaker at Sterling, near Calistoga. Chelini learned to choose the time to pick by observing the vines more than by how the grapes tasted. “We don’t care about sugar necessarily. We look for balance more than anything else,” he said. When vines look tired, the PH is going up and the natural acidity begins to drop. That’s when we pick, when the grapes begin to lose their natural balance.”

Forman had worked and lived on Stony Hill’s ranch while studying at UC-Davis in the ’60s. In 1970, the ranch house became vacant and Chelini moved in, while working for Forman at Sterling. That arrangement lasted for two years. In 1972, Chelini began working as vineyard manager for Fred, who was in his 70s. When Fred decided that he needed to hire and train his successor as winemaker, Forman, who went on to help found Newton, Abreu, Duckhorn, and Forman, recommended Chelini. “For that first vintage, I did all the vineyard work, the tractor work and the winemaking,” Chelini told me, speaking of the 1973 vintage. Nevertheless, he said, “I was pretty nervous about making that wine. The grapes looked perfect. The berry set was just perfect. But I had all of the records of harvests before and this one was almost twice as much. That’s not good, I thought. What did I do?” he told me he wondered.

The verdict? “Fred tasted it and said, “Oh my goodness this is good,” Chelini recalled.

Now the Cabernet Sauvignon. An area of Stony Hill’s vineyard called Top Block wasn’t producing Chardonnay that was up to what they wanted, Chelini said. So they planted Cabernet Sauvignon there in 2004. They first bottled it as a red table wine. When they were satisfied they had a winner in 2009, they labeled it Cabernet Sauvignon.

Back in 1990, when Eleanor’s oral history interviewer, Lisa Jacobson, asked about the red varieties they were growing long before the Top Block conversion, McCrea told her of Chelini’s need for “a certain amount of red in his diet.”

Jacobson: “Was it Mike’s idea, then?”

McCrea: “Pretty much, yes. I noticed that when they planted that field where you come around the corner there, he planted about four rows of Cabernet in there, just to see what they would do. You know, you get interested in seeing what things will do.”

That you do. Wisdom and longevity come from stretching and trying out the new while respecting and holding on to the old that is valuable, including people. Stony Hill has done that for more than 60 years. Bravo!

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.

---

As of 8/8/16 for the next week - sign up for our email and get 25% off your wine order.