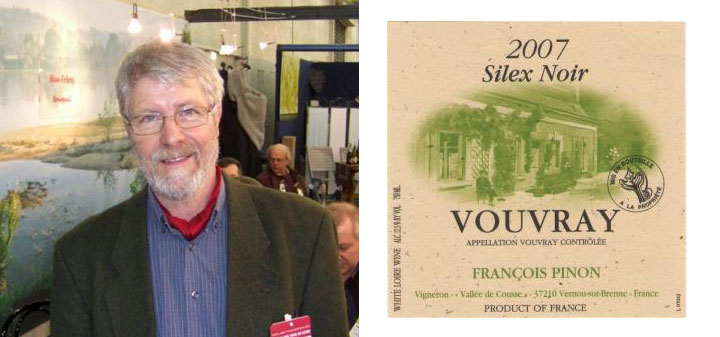

I used to think that Vouvray was vapid, some oversweet slick of a wine that wasn’t worth my attention. Then I went to France’s Loire Valley and visited Francois Pinon, the psychologist-turned-natural-winemaker whose incredible way with Chenin Blanc (the grape behind Vouvray) made me forevermore love and covet bottles of the stuff. I was wrong about Vouvray, and that realization was one of the most exciting palate-pleasing experiences of my life.

Some bearings: Vouvray sits in the Anjou-Saumur-Touraine appellation of the Loire Valley, a winemaking region that stretches from Nantes in the west to Sancerre in the east. Vouvray is pretty much smack in the middle of the 370-odd river-run rambling miles that form this wine-producing powerhouse region.

And while Chenin is grown in other areas of the Loire—including Savennieres to the west and Montlouis-Sur-Loire just across the river from Vouvray—the soil, rich with flint, limestone, a little clay and tuffeau (the white, crumbly calcareous rock prevalent near the river) is especially conducive to growing the grape. “It’s a very unique climate, and there’s a lot of history here, too,” winemaker Benoit Gautier said at a recent tasting. “They grow Chenin in California and South Africa, but it’s not the same.”

“The acidity in Chenin is good for aging,” Pinon told me, and indeed, that’s another great quality of Vouvray: Its potential in the cellar (and the fact that bottles from some of the best producers are $20 and under). That acidity also plays an enormous role in eschewing that poorly held notion I used to have about Vouvray being the fruit punch of wines. That acid holds it up like an acrobat flying through the air in a sparkly jumpsuit. In other words, it’s kind of amazing.

And this balancing magic trick absolutely contributes to the wine’s versatility. In one grape, you can go from snacks to dinner to dessert without even stepping foot outside this sub-region. Sparkling Vouvray is one of the best kept secrets in bubbly, as it’s made in the traditional methode champenoise style. At its best, it can express all the ripe and wonderful orchard-influenced notes of the grape—think apple, peach, and pear—while maintaining that vibrant acidity and the smoky dictations of the soil.. Then there are the still wines, which range from cracker dry to full and lush and fruity, and of course the ones whose late-harvest skins are pierced by noble rot (that good kind that’s responsible for famed dessert wines like Sauternes), to become concentrated, honeyed, and so rich that no confection could possibly compare.

Amy Zavatto is the deputy editor of Edible Manhattan and Edible Brooklyn magazines, holds a Level III Certificate from the Wine & Spirits Education Trust and reports on wine and spirits from New York City.