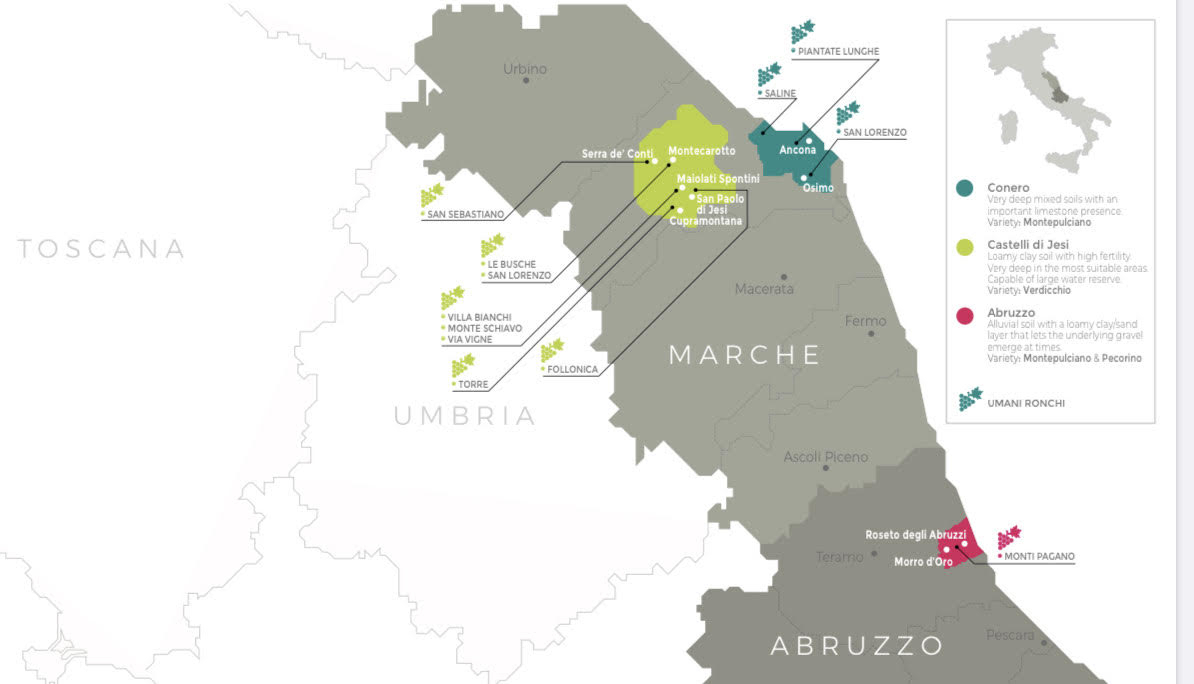

Umani Ronchi is a family-run winery with properties in the Adriatic coastal regions of Marche and Abruzzo. The winery was founded in the 1950s by the Bianchi Bernetti family, in partnership with Gino Umani Ronchi. Its original location was in Cupramontana, considered the capital of Verdicchio, one of Italy's great white grapes. Umani Ronchi now has more than 200 hectares under vine, both white and red varieties, and is run by Michele Bernetti, the family's third generation. Last November, Bernetti stopped by Grape Collective to talk about life and winemaking in these traditional and unspoiled regions.

Lisa Denning: You're a third generation wine maker. When you were growing up, did you think you were going to be in the family business?  Michele Bernetti: Maybe not. Basically I studied economics at university, so I didn't do agriculture or viticulture there. I decided that I probably wouldn’t work in the winery, that maybe I’d do other experiences, like in the food industry.

Michele Bernetti: Maybe not. Basically I studied economics at university, so I didn't do agriculture or viticulture there. I decided that I probably wouldn’t work in the winery, that maybe I’d do other experiences, like in the food industry.

But then — it's a nice story that I remembered a few days ago because it was my father's birthday — I remembered how he sent me a letter once I finished university saying, “What do you want to do?" Not really pressure, but kind of pressure, because he had received a couple of offers for basically taking over the company. So, I was put under some pressure. But before that, I was already basically convinced on joining the business.

I had spent time, even during university, helping my father at the wine fairs, like at Vinexpo in Italy. You breathe the atmosphere in the situation. And then I spent three months in London with our UK importer. Basically, I was working on the road in sales. The excuse was to practice English but then, of course, it was a great experience. I learned much more about the business as well as tasting the wines and enjoying both and so when I got back I joined the company with pleasure and with passion.

Nice. Can you tell me the history of the winery?

The winery was founded in the '50s by a gentleman whose name was Gino Umani Ronchi. Umani Ronchi was his full family name. And a few years later, my grandfather from my mother's side joined the company and he became a partner with Mr. Umani Ronchi. The company was established in Cupramontana, which is a small village right in the center of the Verdicchio growing area, right in the heart of the market. My grandfather was a very well known businessman, an entrepreneur. He had a couple of hotels. He was an engineer. But he had other activities in agriculture because he was passionate about it. He decided to join the company but because he was busy with other things he asked my father to be behind Umani Ronchi. My father had a political startup, basically for a diplomatic career, not for the wine business. He say, "Okay. Maybe I can do it for a few months or a couple of years or something like that." But then he stayed in the wine business. He is the one who really got the passion for it. Mr. Umani Ronchi moved to Rome in the late ‘60s. My grandfather and my father decided to build a new winery near the city of Ancona, where they were living in Osimo and where we actually are based today.  How far was that from the original winery?

How far was that from the original winery?

About 50 kilometers. We still have a winery near that place because of the distance that separates Verdicchio from the Conero appellations and we don't want the grapes to go around, up and down. We have the other one out there where we do the vinification of the white wines. And then we bring the wine to Osimo for the bottling. And so Mr. Umani Ronchi moved to Rome, sold his part of the shares, and we became title proprietor. We decided to keep the name because the name was already established in the market, particularly in the domestic market. So we wanted to keep the name and then as a family we developed the business as it is now.

Wine writer Ian D’Agata has called Verdicchio Italy's greatest native white variety. Can you explain why it does so well in Marche?

I think it's interesting because even a few kilometers south, Verdicchio doesn't come out very well. It appears to be more than climate. I think it's a combination between soil, the important presence of clay in the area which Verdicchio benefits from, and probably also climate and the type of the hills that are there. It's not flat but it's not too steep. In gentle hills I think it really comes out very well.

Don't forget that the same grape, Verdicchio, is now recognized as the Trebbiano di Lugana, grown up near Lake Garda, between Lombardy and Veneto. They call it Trebbiano di Lugana but from the DNA point of view it is Verdicchio. But if you taste the Lugana wine, it's completely different. There are some similar characteristics, but Lugana is less alcoholic, less concentrated. It’s a bit more fruity than Verdicchio which is a bit more bold in terms of a structure and profile. So, probably, it's a varietal that we have found in this nest, in Marche, in this part of Italy.

Can you tell me a little bit more just about Marche as a region? How would you characterize it? The tourist office calls it “Marche, Italy in one region”. Why? Because we have mountains, we have a lot of hills, we have the seaside, and many soils with a concentration of different topographies. But, to me that is too generic.

The tourist office calls it “Marche, Italy in one region”. Why? Because we have mountains, we have a lot of hills, we have the seaside, and many soils with a concentration of different topographies. But, to me that is too generic.

I think the best description was given by the New York Times as "Italy's best kept secret” because it denotes the character of the Marchegiani, or the people like me that are living there. We are modest and not too loud, we are not so good at showing off. The people from Marche are hard workers and it's a very famous market for small family businesses. And maybe it reflects the reason why Marche is not very well known. It's not because people don't want to show the region to other people, it's just because we are not capable of it. We're not very good in communication from this point of view.

But Marche is fantastic in terms of what is, I think, it's one of the best in this moment. It's one of the regions where you can see the real Italy because it's quite unspoiled from tourism. You go to other regions and you see many vendors and there’s much more tourism even in the small villages that are starting to change and you don't find as many small food shops. Marche is still the same as it always was, the people living with the keys on the door. It's very well maintained in terms of the old villages, the old part of the countryside. It's very intact and original.

How do you think the Marche region can get the word out about its wines?

I think it's up to the producer and up to, of course, the institution. But mostly to the producer. Unfortunately, or fortunately, we don't have big investors in the Marche wine business so you don't have the big budget in terms of promotional activities. The best way, in my opinion, is to bring people in, tourists, since we don't have a big number of producers going around the world and spreading the word. At the same time it’s up to the producers to found ways of communication that are a bit more modern and where you can get some good results without spending a big budget. And that's what we are doing at this moment. During the past several months I have been coordinating the consortium for the Verdicchio. It's been around for a while but, it's been a bit quiet. So, now there is a strong demand from the producers to improve the communication and the other promotional activities. And so, we are collecting the ideas and we are putting down a plan.

Some of your vineyards have been certified organic for many years. How much of your production is organic and do you plan to increase that amount?

Currently around 45% of cultivated vineyards by Umani Ronchi are certified organic. Next vintage we’ll add 15 more hectares within the Conero DOC, bringing the total to around 105 out of 210 total.

Is your goal to be 100% certified organic?

Yes. At the end I think of it in terms of quality. We started organic farming as a responsibility, to have a lower impact of our agriculture in the local territory. And also for the people working in the vineyard because I think it's better for them to work with organic products. So, it's been a choice that has been related mostly to the local territory and people, not for marketing. And in Abruzzo, in Conero, we have lesser percentages of organic vineyards. Why is the percentage lower? We've been a bit more cautious because Conero is an operation that is very close to the sea. And Montepulciano is a late maturing varietal. We harvest in the second part of October. It's a combination that can be a bit dangerous because of the humidity, because the fogs that you get in October, because of the sea. And the fog is very corrosive on the grape, on the skins. So, we've been more cautious. And can you tell me more about your vineyards in Abruzzo?

And can you tell me more about your vineyards in Abruzzo?

Yes. It has been an expansion that we did in the year 2000 when we bought our Abruzzo estate, 35 hectares in Roseto degli Abruzzi, which is the northeast part of the Abruzzo region. It's quite a large and beautiful place. We decided to grow Montepulciano because it was already planted in the vineyard. And then we planted some new vineyards with Montepulciano. And some Pecorino which is the other, white grape. It’s the other varietal that is very much typical there.

We converted the Abruzzo property immediately to organics because of the latitude and since it's a bit more inland, the weather conditions were perfect for the organic farm.

How would you describe your Abruzzo Montepulciano wines to someone who's never tasted them before? I think they can be compared to the Montepulciano grown more north in the Conero area where you find a bit more elegance, a bit more finesse, maybe less structure than what you get in Abruzzo. And also you feel a bit the humidity, the temperature. You feel the warmer climate. So, the Montepulciano in Abruzzo gets more spicy, a bit more bolder, the color is more intense, concentrated. The wine can be tannic and that's what we try to avoid. They tend to be a little bit more rustic.

I think they can be compared to the Montepulciano grown more north in the Conero area where you find a bit more elegance, a bit more finesse, maybe less structure than what you get in Abruzzo. And also you feel a bit the humidity, the temperature. You feel the warmer climate. So, the Montepulciano in Abruzzo gets more spicy, a bit more bolder, the color is more intense, concentrated. The wine can be tannic and that's what we try to avoid. They tend to be a little bit more rustic.

Pecorino is different because it's a varietal that ripens very early and has a beautiful profile in terms of acidity. I think it's very much like Verdicchio. I think it's an excellent example of a good Mediterranean grape varietal in the sense that there are wines that are not too aromatic on the nose. They are a bit more shy on the nose, yet still beautiful on the palate. They have this beautiful, I’m sorry to use the word minerality because I don't really like it, but it has a distinct mineral character.

You have more aromatic wines in the north of Italy, even Soave. But in the peninsula part of Italy, I think the whites become a bit more shy on the nose, Greco, Fiano, even Vermentino. And Pecorino is in that profile. It's a grape that is part of a family of grapes in which there is Falanghina and there is another grape from Emilia-Romagna, which I don't remember now for what wine. And they were brought over by the ancient Greeks who arrived in southern Italy. And they found, through the DNA, that they are connected in some ways. And I think when you make wine with Pecorino that, while they don't have the strength or the complexity of Verdicchio, they're very serious. They're not too big or too fat. They have good acidity and are fresh, exactly what we are now looking for in a white wine.

What is the total production of all your wines and how much do you export?

We produce about three million bottles, which is about 250,000 cases. And we export 70%. We have a good presence in Asia and of course in Europe, United States, and Canada. So, my thinking has always been very much oriented to export. And a very important market is Asia, particularly Japan, where we are very strong. We actually opened three restaurants in Tokyo. Our Japanese importer has a connection with a big restaurant group in Tokyo and they wanted to open a kind of Italian restaurant and they decided on Marche wines, so they opened these three wine bars in Tokyo which carry our name.

How would you sum up your philosophy of winemaking?

We consider our territory, to be what we call the Adriatic wines, because Marche and Abruzzo they all face the Adriatic sea. And the border between them is more of an administrative border rather than a real border. The climate of Abruzzo is, because it's more south, slightly warmer, but it's quite similar. The Adriatic is there and it's important in terms of the winds that create the conditions. And also the soil is not so different. So, we consider that this belt by the Adriatic is something that I think has more things in common than what you may think.

Our philosophy is to make wine from this area that are, as we say, “Grandi vini ma non grossi vini,” great wines but not big wines. And this is a philosophy in the winemaking and also in general. I think it fits with the Marche, and the wines are like the people of Marche too. Wines that are not too bold and not too muscular. We're trying to find a bit more elegance. And this is the philosophy that we have in the winemaking, for sure. You’ll never find our wines very big, very rich. You find a bit more, maybe a little bit more acidity, rather than strength.

And those are always great food wines.

Absolutely. This is how the wines work very well with food.

What is the food like in your area? Le Marche is the only Italian region which is plural because the region is quite diverse, and in terms of its food too. So, it depends where you are in the north of Le Marche or the South. But, in general, I would say that, especially on the coastline, fish is always very important. We have some of the most important fish markets in Italy, in Ancona, San Benedetto del Tronto. Even in Abruzzo, fish is very important. And the fish, I think, at this moment, is one of the places where you get the best fish in Italy and at the best price as well.

Le Marche is the only Italian region which is plural because the region is quite diverse, and in terms of its food too. So, it depends where you are in the north of Le Marche or the South. But, in general, I would say that, especially on the coastline, fish is always very important. We have some of the most important fish markets in Italy, in Ancona, San Benedetto del Tronto. Even in Abruzzo, fish is very important. And the fish, I think, at this moment, is one of the places where you get the best fish in Italy and at the best price as well.

What kind of fish?

The fish in the Adriatic is quite different than what you get in the ocean because the sea has more shallow waters and this explains why the fish is very tasty. And the size also, the fish is a bit smaller, not as thick. So, you don't find fish like sole or sardines. We have this incredible diversity of fish from tuna to swordfish to smaller types of fish. And that's why the cuisine is so different.

A very famous dish is the fish soup, which is called brodetto and each small village has its own recipe and everybody says that theirs is the best. In Ancona we don't use mussels. In the south of the region, they started using pepperoncino, which is a chili pepper. In Abruzzo more and more in the southern part of Abruzzo, people even use a bit of saffron. In San Benedetto del Tronto, they use vinegar because they used to cook the brodetto right on the boat when they were fishing.

How interesting.

Initially, it was the soup that was cooked with the different parts of the fish and there are about 12 types of fish. Because they didn't have any refrigeration system in the late past, they were using green peppers because otherwise if they harvested the ripened peppers, and they didn't keep wine aboard because there was no way to preserve the wine. They were using water with a bit of a vinegar and so they put it in the soup too. More inland is, I would say, is a cuisine that reminds you a bit what you have in different places of central Italy, even Emilia-Romagna where fresh pasta is very common and with the use of farm animals like chickens, rabbits, and veal.

Visit TheWineChef.com for Lemon Shrimp Risotto to pair with Umani Ronchi Verdicchio.

Read more about Marche and Abruzzo on Grape Collective:

By Valerie Kathawala:

- Making a Case for the Marche: Is Verdicchio Italy’s Greatest Native White Grape Variety?

- "Unheard of!' No More: Riccardo Baldi Wants to Put the Marche on your Wine Map

By Christopher Barnes:

- Italy's Hidden Gem: Rocco Vallorani of Vigneti Vallorani on Southern Marche

- Aroldo Bellelli of Bisci on the Elegance of Matelica Verdicchio

- Going Organic in Castelli di Jesi: Claudio Caldaroni of Col di Corte

- Interview with Chiara De Iulis Pepe of the Iconic Abruzzo Winery Emidio Pepe

- Francesco Cirelli Is Walking on the Wild Side in Abruzzo

- Valle Reale: The Mountain Wine of Abruzzo

- The Native Grapes of Abruzzo: Camillo Zulli of Cantina Orsogna

By Dorothy Gaiter: