In 1986 Zlatan Plenković started his wine journey on the island of Hvar off Croatia's Dalmatian Coast. Becoming an official winery in 1991, it was only the second private winery in Croatia formed in the wake of Yugoslavian communism. The winery was established in a small fishing village called Sveta Nedjelja about an hour drive from Hvar City, the main city on Hvar. Zlatan was a poor fisherman who literally hustled his was to creating the second largest private winery in Croatia. He started by developing a modest hospitality business and making small amounts of wine for his guests. Over time through the force of his personality he convinced growers to sell him grapes on credit and expanded the business. He eventually took on vast quantities of personal debt to build what is one of Croatian wine's great success stories. All the while the family maintained a dedication to quality winemaking making wine from vineyards in rocky hillside locations, handpicked with low yields and organic viticulture.

Zlatan Plenković died in March 2016 and the winery is now operated by his children Nikola and Marin and Antonia.

Nikola Plenković talks about his entrepreneurial father and the constant fighting with the post-communism bureaucracy and his championing of the Croatian wine industry.

Christopher Barnes: Nikola, talk about the Croatian wine industry. How has it evolved over time?

Nikola Plenković: The Croatian wine industry began when the country started, in the '90s. We separated from ex-Yugoslavia and we started to become Croatia. In the beginning, there were a few private wineries in Croatia. One of them was ours. It was named Zlatan Otok. My father started the second private winery in Croatia. The first was Enjingi.

People realized that they can make a living from wine or growing grapes, because of this particular area. Also we buy from people in the village. They are our cooperatives. We pay them for their grapes, and that provides them with a living.

It was a poor village like this in Sveta Nedjelja. You see how far you need to come from Hvar City. It is one hour by road. This road was built in, I think the '60s or '70s. This road here, to Sveta Nedjelja, was not a road. They traveled by mules and horses to the hills, and on the other side for a ferry to Split and elsewhere.

I think the reds have become famous in Croatia. Also the whites. Pošip has become famous in the last few years. There is also Malvasia from Istria, which is also very nice. It's lighter than Pošip (which is the famous Dalmatian white wine). Also, you have a good Graševina (better known as Welschriesling) in Slavonia (a continental region in north-east Croatia - beside it being known for the Graševina grape, is probably most well-known for its oak barrels). Now we have started to show the world that we have good wine in Croatia.

It was not like that in the past. Everyone can sell a little bit in Croatia and maybe the surrounding countries like Bosnia, Serbia, Austria, and Slovenia. But the price was very low in these ex-Yugoslavia countries. People didn't buy expensive wines. You can sell cheap wines but you can sell cheap wines anywhere.

Our plan as Croatian winemakers, because we have to be united as a group, is to go together to the Decanter Wine Awards in London. We’re going to ProWein in Düsseldorf. We go to Vinitaly in Italy. My brother was there yesterday. We want to show people that we have fine wine. If you go alone and you are here at one fair, for example In Düsseldorf , in ProWein, there may be 10 houses in this place. If one is here, one there, one there, nobody will see you. You say, "Where is that?"

But also Croatia is increasing in tourism. The wine tourists, they’re coming like crazy. I have that restaurant, and they start to come and they want to come in like crazy, but also I like when the visitors come because people then eat something, buy wine.

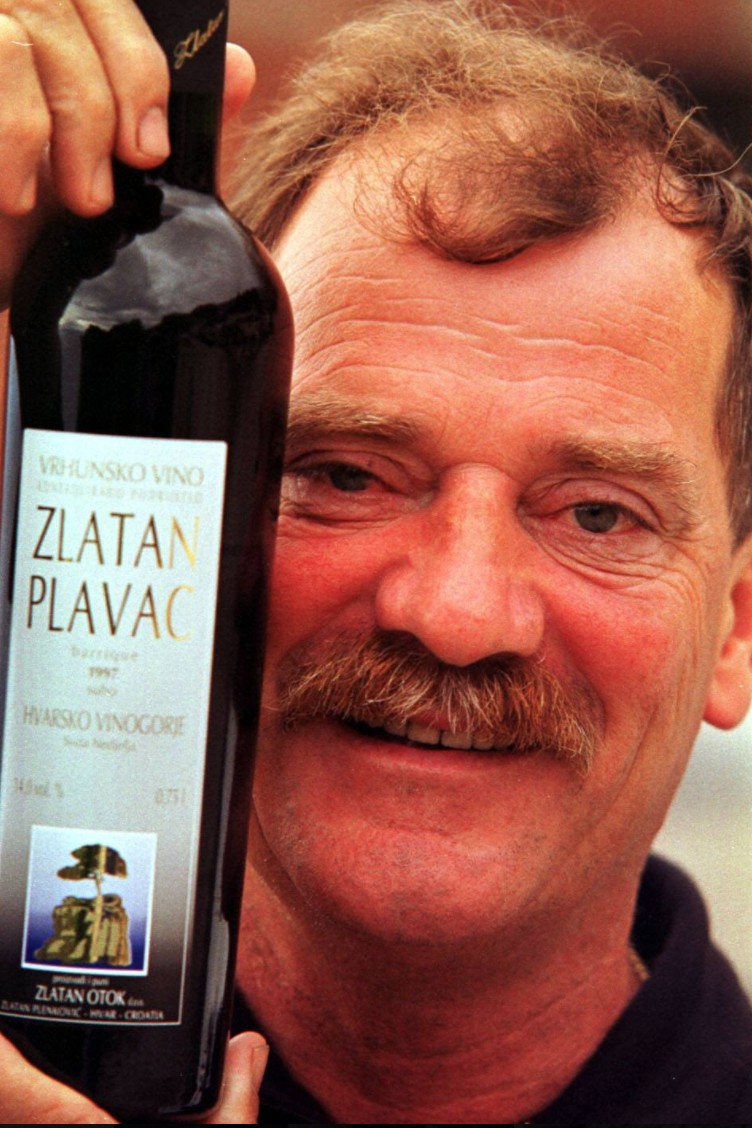

(Croatian wine pioneer Zlatan Plenković)

Nikola, talk about the philosophy of winemaking and viticulture at Zlatan Otok.

At Zlatan Otok our philosophy starts in the vineyard because my father was producing a small yield, less than half kilo per one plant. As a result, our wines are extra full bodied and I think good, good wines all over, not just because they are Croatian wines. We make wine with passion because my father loved making wine. Also, my brother and I love making wine.

We don’t release red wines before three years. The best wine is five or six years old when it leaves our winery. Our philosophy is the best drinking wine is from five to 10 years, which are wines that have from 14 to 15 alcohol, 36 to 38 extract. For white wines, we started before it was a philosophy that wine need to have a little bit more color, more body. Now, the world is acknowledging that it likes light wines. Very aromatic, very fruity, very fresh. We now release year to year. Now it's 2017, we put out our 2016, because it can go two or three months. It needs to pass five, six months before you can let it go out into the market.

Also, now rosé is popular. This year, we sold 80% in advance, before it was bottled. We bottle before 10, 15 days. But we have orders from Russia and the USA. My brother is in the USA. It was very well received and they want to buy more and more rosé.

We have more than 100 medals. We have international medals, like in Bordeaux. Plus, the best wine in show in 2005. Last year in Paris, we got the gold medal also for our Grand Cru.

Unfortunately, my father died last year. He had a lot of heart attacks and he had one on the ferry as he was coming back from Paris. He went to receive that big medal.

I think now Croatian wine is known worldwide. Now there are about 15 to 20 serious wineries who do a good job and make good wines—very, very good wines. Also, they export to the world.

Take a 360 degree virtual reality tour of the Zlatan Otok winery. This experience only works in certain browsers including Google Chrome. You can also experience the VR tour directly on Youtube.

Nikola, talk a little bit about what happened to the wine industry during communism.

During communism, when it was Yugoslavia, it was in the '90s and it was forbidden to be a private winery. My father was going about in the '80s, going to Hvar and asking, "I want to make my own wine," and they said, "If you say it one more time, you will go to prison." There were only cooperatives, but they were state cooperatives and they took wine from here, there, everywhere in the boats. They took it cheaply, of course. They then sell it around.

It was communism. Nobody could have their own wines. No private wineries. You need to work for the state and it's known in the world now like in North Korea. In 1989 Enjingi was the first one who made a private wine. And my father saw it and said if he can do it I can do it.

Is that Plavac Mali? What kind of grape was he making?

Is that Plavac Mali? What kind of grape was he making?

He made this 7.5 deciliter bottle with a cork with Plavac Mali. It was only for our guests, at first. Then when the guests liked it, he started to sell it. In the '90s we made 1,800 bottles. In '91 we had 180,000 bottles.

After that, he started to sell a lot.

In the beginning it was white wine. Our white wine, Zlatan Otok, became famous. In '95, the Pope came to Croatia, drank a glass and said, "Give me more." It is known that the Pope doesn’t like too much wine. Then a journalist published it in a newspaper and then things became crazy. People saw that Plavac Mali was a good wine.

After that, in about '98, we produced about 350,000 bottles in a year. Now we produce about a half million bottles a year. We can sell now 700,000 to 800,000 bottles a year. We want to sell it now. Because of that, we go to the USA, to China, to all these countries around us.

Tell us how your father, who came from a small town on Hvar and was not from a wealthy family, managed to build a company into the biggest private winery in Croatia. That's quite a story, isn’t it?

My father started as a fisherman. He was from a poor family and at first he went to work digging fields, digging lavender. Everything. It was August and 40 degrees outside and he would be in the field all day. He was a visionary, you know, and then he started to fish. When he made some money from fishing, he started to build a guest house. Then he started tourism. The first guest was here, I don't know, in the '60s, I think. Around the '70s he started to build the guest house and then we had breakfast, dinner, and sleeping.

All of us worked there - my brother, sister and my mother, and all our relatives. Everyone was working there. From that beginning he then started to make wine for our guests and they liked it. They wanted to buy it, but he didn't have enough. In his first year, it was, I think '86, we had 200 bottles for ourselves to provide gifts for our guests because in those days, if somebody came here, we needed to appreciate them.

Then when he started he was always around all these politicians. He would go for a tour to Hvar. For all this, we built 27 kilometers of roads in these fields and we did it on our own. The country didn't help us at all. Also, the marina, he had a vision and he put a lot of money into it. It's not rentable like the restaurant and the port, but it's good for marketing wine because everybody comes. After that, they called me or emailed my company and said, “We'd like to buy your wine." In almost every country in Europe you can find our wines.

Then when he started he was always around all these politicians. He would go for a tour to Hvar. For all this, we built 27 kilometers of roads in these fields and we did it on our own. The country didn't help us at all. Also, the marina, he had a vision and he put a lot of money into it. It's not rentable like the restaurant and the port, but it's good for marketing wine because everybody comes. After that, they called me or emailed my company and said, “We'd like to buy your wine." In almost every country in Europe you can find our wines.

It's challenging being a winemaker on Hvar with its isolation. How you are able to become so successful with all of these logistical and marketing issues?

It's very difficult to have a winery. Not only the winery but other things because we have transportation issues. The ferry, it's very big money to have trucks. I need to take bottles from the property. Also now, I buy them from Italy. Then I need to transport them from Italy to here on Hvar. You see all these small roads, it's very difficult. We’re fighting now, my father fought to make this road and he made it a small one. Now they are starting to widen that road and I hope in three years (they said) it will be complete because Hvar is 15, 17 kilometers on that road. Round trip, it's 45 kilometers. The challenges are big here— to make wine and make great wine. Everything is best if you see this winery. It's not a showpiece; I can't do that because I spend a lot of money on my trucks, on transportation, and people. Everything, corks, boxes, everyday things like tanks, all this equipment is for making wines. It's very expensive and I need to bring it here. After all that, I need to load the boxes into my trucks and go out to Split and elsewhere.

It's expensive, very expensive. For transportation, only one ticket for the ferry, it's $100 or something to get there. I also need to travel all the time. I need a car, I need to pay for all of that. And the country doesn't support us very well. That is a bit of a shame for our country, but we keep going up with all this and every year it is getting better again. I think all Croatian wineries will grow better and better, and in maybe a few years, everybody will know Croatian wines.

You became very successful because you focused on quality from the beginning. As you have grown, you're now producing a lot more wine at different price points. How do you maintain that quality?

All our wines are top quality wines. Perhaps not all, but 90%. We have this Zlatan Otok first wine. It's quality wine because it's also from the Hvar and it can be top quality because we have some things, some grapes inside which are not allowed to be top quality. Also, we now have more and more wines, but we maintain the quality because in all our vineyards, we put all our money, what we earn from the winery, back into the fields, in the equipment, and everything.

Tell us about the terroir in Hvar. Talk about the climate and the soils that you have here.

Tell us about the terroir in Hvar. Talk about the climate and the soils that you have here.

On the south side of Hvar, it's like Dingač and Postup. It's very steep, from 40 to 60% gradient. The soil is very rocky, very minerally. This is the most ecological position in the world here because there is no poison. Then when it rains, the water comes down and the rocks take the humidity and plants can live from that humidity. On the north side of the island, it's more soil, it's more earth. It's less rocky and it's flatter. When there is a lot of rain, the water stays on the surface and everybody knows that when the sun comes out after a rain, when the humidity goes up, then there is the potential for diseases because diseases are in the soil. Not in the leaves or in the plant. Then they come into the leaves, or to the grapes. On the north side, you need to put all these substances.

Talk a little bit about the types of soils that you have here.

Here, it's a very rocky soil disposition. In seven kilometers there, you have half rocky, half brown earth. Then you go on the north side and you have what we call genunetsa. It's red terroir and it's a very different taste from the other positions. On the north side you have steep positions like here. There is, we call it cerabone. It's like sand. There again, it's different.

I think you need to know what to plant in every soil area because every soil is good. You can't put Plavacs in that red soil. You can, you can plant it, but then you wouldn’t have the same quality as here because you have two kilos, because there’s more rain, more humidity. It can't be full bodied.

Zinfandel. There were studies showing that Zinfandel originally came from Croatia and Zinfandel is one of the parents of Plavac Mali. Talk a little bit about that.

Zinfandel, it's the same as Primitivo or same like Crljenak. In Croatia they call it Tribidrag. I don't know if you have more names because here you have dialects and everybody calls it something different.

The Croatian Institute asked my father because he's friends with them, if he can give one soil here in this position, one vineyard to put all the clones. Because in the start, they had some plants that they said were like Zinfandel, but of course, the Italians don't want to admit it. The USA doesn't want to admit it.

Then they took all this DNA, genetic material, and then they had to admit it comes from Croatia because the oldest plant is found in Croatia. I think it has big, big potential, but you need to be very careful with it because Crljenak, it's a very sensitive sort of grape.

Crljenak crossing with Dobričić (another native Croatian grape) evolved into Plavac Mali. It was coming naturally.

Nikola, are you organic?

All our wines are organic. In Sibenik, it is now on our label, because you need to have a five year period and they track you so that you don't put anything bad in the soil or on the plants. Here, this position in Hvar, is the most organic in the world. It's very, very important for us. We don't need to put anything on these plants. For Makarska and Sibenik we need to, because we will not take anything from the vineyards, but it’s all organic things.

For more on Croatian wine check out:

Ivan Miloš on the Pelješac Peninsula

Želko Garmaz's Grape Collective feature Croatia: A Land of Wine Stories

Georgio Clai is Putting Istria on the Map

Also check out our interviews with Mike Grgich and Professor Carole Meredith