Two men, accompanied by armed guards, drove through the streets of Southeast Turkey. Explosives litter the air. It very well could have been the opening of the next James Bond movie. But in the seat where the sophisiticated superspy might have sat was instead a winemaker, visiting one of his contract growers.

In few places since the fall of communism has the political situation impacted the wine industry as much as in Turkey. In 2013, the current government controlled by the Justice and Development (AK) party pushed through a controversial law significantly harming the alcoholic beverage industry. Taxes were drastically increased, advertising or sponsorship of alcoholic beverages was banned, and restaurants near mosques were forbidden to sell alcohol. What makes the laws seem even more Draconian is that, according to The Guardian, at only 1.5 liters a year, Turkey has the lowest per capita alcohol consumption rate in Europe, and 83% of the population does not drink at all.

Therefore, as one might expect, these political circumstances are a very serious problem for the wineries; and there are fears that the problems are only getting worse. Ali Basman, Managing Director of leading Turkish wine company Kavaklidere, spoke emphatically about not contemplating any new investment until there is some sort of resolution to the current political problems. And writing on Jancis Robinson’s Purple Pages in 2014, Turkish wine critic Umay Çeviker commented: “Turkey 2023 is this a vintage prediction or some sort of prediction on climate change? No, it is the date wine producers in Turkey fear because of the long-standing Erdoğan government's mission to turn the secular system into a religious one by the centenary of the young republic founded in 1923 by Kemal Atatürk."

One winemaker we spoke to estimates that since the most recent round of regulations, 50% of the wine and liquor sold in Turkey is now sold on the black market. And whereas black market wine is merely of much lower quality, the unregulated raki, the popular local liquor, has proven to be downright dangerous, even causing fatalities.

The vineyards of Sevilen in Izmir

Unfortunately for winemakers, their concerns extend far beyond government regulations. The domestic retail environment has shown to be outwardly hostile. Retailers and bars have come to expect and often demand kickbacks, either in the form of little brown envelopes stuffed with cash, or wineries buying wine fridges or other equipment for them. For the established wineries, the problems are daunting enough; but for the group of boutique wineries that are less than five years old, the problems could prove to be fatal.

But in spite of all of these outsized obstacles, the industry has exhibited incredible perserverance — the winemakers are even starting to find their feet in terms of developing and meeting industry-wide standards of quality. As a result, the region is producing native varietals that are truly distinctive and vibrant. You might draw comparisons to international varietals, but those tend to fall flat. The big tannic Boğazkere is similar to Tannat, yet not really. Kalecik Karası could be linked with Pinot Noir, but it is a shallow comparison.

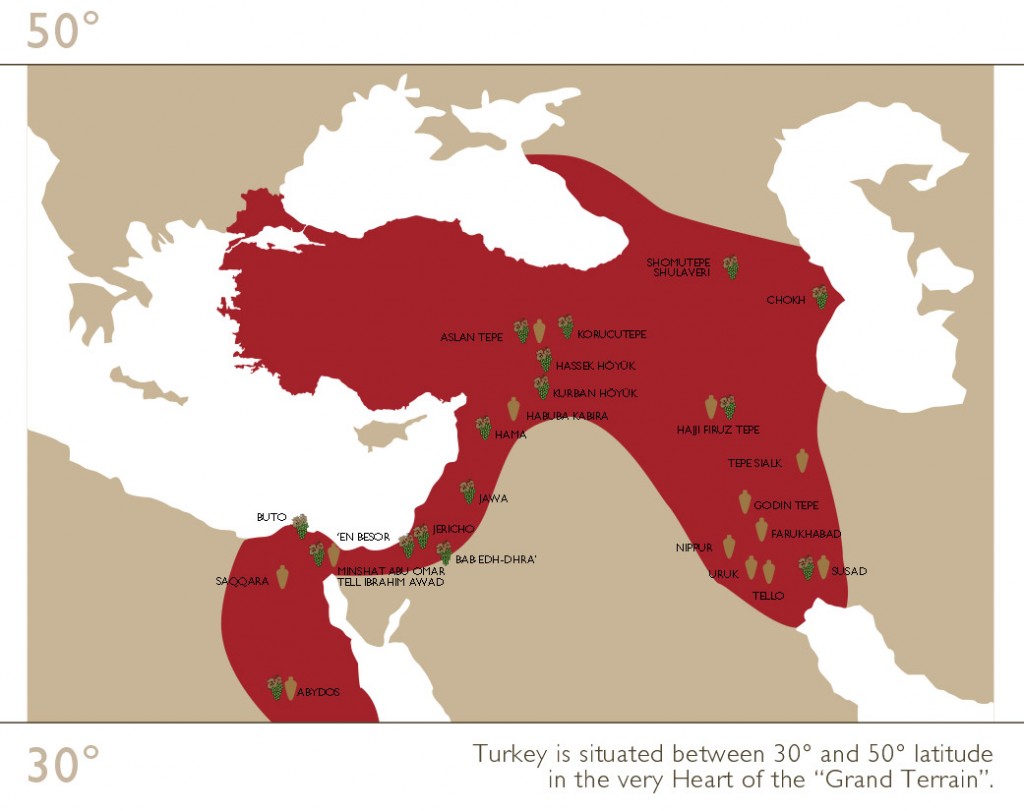

The Turkish wine industry, while very new, is also an old one. The southeast of Turkey was the origin of grape seeds, and grape domestication in the region dates back to 9000 BC. The first traces of viticulture and winemaking in Anatolia go back 7,000 years. Wine in the times of the Phrygians who lived in Anatolia after the Hittites was an essential part of daily life. They introduced wine to the Greek colonists in West Anatolia and by the sixth century BC, wine was being exported as far as France and Italy.

Right: Traditional winemaking at Kavaklidere.

There are native grapes whose genetic substance goes back to these early times. Native grapes such as Boğazkere, Oküzgözü, Narince, and Kalecik Karası are unique, and top wine critics recognize the potential of the grapes. When the wines are not masked by too much oak — as can be the case with several of the reserve wines I tasted — the wines are fresh and vibrant. Financial Times wine critic Jancis Robinson wrote of Öküzgözü as far back as 2009: “I've fallen in love with a grape variety that's entirely new to me. I can neither pronounce nor spell it with ease in its native language but am told that its name translates as Bullseye, which strikes me as a pretty good name for a red wine that is round and fruity, with so much charm that it makes you smile when you taste it.”

Over the past 10 years, with the arrival of international wine consultants and the rise of boutique wineries, the quality of Turkish wine has greatly improved. Consultants such as American Daniel O’Donnell, Bordeaux- based Stephane Derenoncourt, and Piedmontese Marco Monchiero are all part of the movement towards greater quality. Murat Guner, owner of Sevilen winery in the Izmir region, pointed to a focus on viticulture and improving vine stock.

“First, we changed our vineyards," Guner explains, "and then we changed grape varieties because before then we were using table grape varieties. The results were not very good. After, step by step, the quality of Turkish wines has been increasing.”

If there is a silver lining to the political problems, it may be that it is forcing the Turkish wine industry to shift focus towards the export market. Prior to the troubles, the Turkish wine industry had been primarily focused on domestic consumption — even today exports still account for less than 5% of sales.

American wine consultant Daniel O’Donnell, who has been working as a consultant for the last 10 years with Kayra, the former state owned wine and liquor company, feels that Turkey still has a lot of work to do establishing itself in the international marketplace.

“It’s not so much that Turkey has a perception of good or bad," he says. "It's that Turkey has no perception. It's just not on that map. So getting it on that map, I think, is critical to the success of the industry in Turkey given the governmental pressure. Having great quality at a reasonable price is the only way of doing that, and these things just take time. I mean, how long did it take Chile to do it and how long did it take Australia to do it?”

Ennio Gugliotta and consultant Marco Monchiero at Vinkara near Ankara in Central Turkey

A significant challenge is how to market wines made from grapes that most Westerners can’t pronounce. Writing on his blog in 2010, wine critic Tim Atkin addressed this problem: "I think Turkey needs to keep its native grapes off the front label and come up with some brands that are recognisably Turkish but don't sound Islamic or rely on images of mosques.“

Of all the wineries we visited, only one could be considered a boutique winery, and it does not export to the United States. The boutique wineries seem to have a particularly tough time from an export-import perspective, between the government restrictions and the lack of infrastructure and know-how. As seen in Chile and Georgia, a successful model for countries trying to showcase their wines is to promote artisanal, small production wineries. As Turkey evolves, figuring out how to give the small producers a voice in the international market is a challenge that needs to be addressed.

Grape Collective spoke with Sal Gulderen, manager of Turks and Frogs, a Turkish-owned wine bar in New York City's West Village neighborhood. The 13-year-old wine bar carries 12 Turkish wines on its list.

"The only people who know about Turkish wine are people who have visited Turkey," Gulderen says. "Once people try the wines, however, the response is almost always positive."

According to Gulderen, the Turkish wines that garner the most positive response are those made from the Boğazkere and Kalecik Karası grapes. He feels the largest challenge for Turkish wines in the US is the limited availability of the wines in stores and restaurants as well as the small number of producers represented in the US.

Left: The harvest at Kastro Tireli in the Izmir region.

Left: The harvest at Kastro Tireli in the Izmir region.

If the political problems can be worked out, the ceiling for the Turkish wine industry is high. After 10 years of working with Turkish grapes, Daniel O’Donnell is excited about the tremendous potential.

“These, literally, are treasures — undiscovered treasures in the wine world," O'Donnel exudes. "And for Turkey as a country to embrace that, I think that's the way that Turkey will end up being known in a significant way.”

As we move into a post-Parker, post-points world, a wine’s uniqueness is becoming an increasingly important part of its value determinant. Sommeliers, bloggers, progressive retailers and the new breed of millennial wine drinkers are embracing exploring difference in wine. In Reading Between the Vines, Terry Theise wrote: “I want to live in a world of thousands of different wines, wines whose differences are deeper than zip code, each of them revealing fragments of the unending variety and fascination of this lovely green world on which we all walk.”

The native grapes of Turkey are unique, compelling, and delicious. There is great passion among the Turkish winemakers, a belief in their terroir, in the beauty of their grapes and a desire for their wines to gain recognition outside of their country. It is only a matter of time and political circumstance before Turkey becomes an important part of the mosaic that is the world of wine.

Interviews with Turkish winemakers:

Daniel O'Donnell and Kayra winemaker Özge Karmein, Kayra

Interview with Murat Güner of Sevilen.

Interview with Ennio Gugliotta and Tina Lino of Vinkara wines.

Interview with Isik Gulcubuk of Kastro Tireli in Izmir.