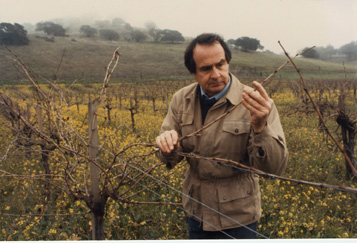

Warren Winiarski is the American winemaker whose 1973 Stag's Leap Cabernet Sauvignon came out on top during the 1976 Judgment of Paris tasting which helped establish Napa Valley as a top international wine region. A bottle of the award-winning 1973 S.L.V. Cabernet Sauvignon wine is on display at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and in its November 2013 issue, Smithsonian magazine included a bottle of the Cabernet as one of the “101 Objects that Made America. In 2007, Winiarski sold Stag's Leap Wine Cellars for $185 million to Marchese Piero Antinori and UST Inc. (now Altria, which owns a smokeless tobacco manufacturer and Ste Michelle Wine Estates.)

Read Dorothy Gaiter's Grape Collective column about Warren Winiarski.

Dorothy Gaiter talks to Warren Winiarski about the Judgment of Paris, winemaking and Napa Valley today.

Dorothy Gaiter: I've seen many references to that 1973 wine. It was not your first release. It was your first estate wine, correct?

Warren Winiarski: It was the first wine made at the winery. In 1972, we had grapes, from the grapevines that I planted in 1970. This is an important factor, that these grape vines produced that wine in 1973 were only three years old.

That's amazing.

Because of the story, the belief in many quarters, that vineyards need to be old to make good wine, and to make great wine, they need to be venerable in their age. To make great wine, they need to be venerable in their age. It's an important factor, and I can go into that aspect of it if you want a little bit in depth why that's the case, but to follow the chronology of the origin of that '73 wine, the grapes for that wine were planted, the rootstock was planted in 1970. They were grafted. The budwood was placed in the rootstock in 1970, and so it made what the viticulturists call its first leaf, mainly its fruiting variety leaf. It made that first leaf in 1971 and grew the main shoot from the bud, the cyan bud, into a trainable structure of the vine in that first year.

You got actual grapes.

In 1972.

In '72, and did you make wine from that?

Yes, it was made at another winery.

The first wine from your winery was '73.

In '73 we built the first building at the winery. You'll have to visit it some time because the visitor center is a structure that I co-designed with a man named Javier Barba of Barcelona. It’s an effort to unite nature and art in some structural way, some tangible way. Anyway ... 1973?

How was it that your wine got to be entered in that? Did they ask you or did they just purchase it?

I got a call from Robert Finigan. He had a wine journal that was published I think every other month. He allowed himself to be a food critic and a wine critic, and he was actually very good in the beginning in finding many of these new wineries and talking about their wines, and that was very important in the beginning for a growing number of people who became in love with wine and wanted to know more than their secular activities could tell them unless they had somebody writing about it, and Finigan was one of these people.

Anyway, he called me one day and he said, "Would you care to have a visit from a woman named Patricia Gallagher? She is the colleague of Steven Spurrier, an English wine merchant living in France, and he has a wine school and he has a little restaurant also in the Madeleine area of Paris. We were desperate to get people to talk about us, and so I only hesitated a fraction of a second before I said, "Of course. We would love to have her visit."

She had a friend from college days who was a member of the family who had a nursery in Napa for plants for retail sale to people who needed plants for their gardens and their landscaping. So she came to Napa and she wanted to visit with a number of small wineries that Finigan would recommend were at the cutting edge of what was going on beyond the major wineries. At that time, there may have been 15 wineries in Napa.

That was a long time ago.

Yes. This would've been in '75. There may have been a few more, but the four big ones - Christian Bros., Beringer, Charles Krug, United Vintners, the co-op - let's see, what else would have been ... Those were the major ones, all in the same area. So we had a knock on our door, and there was Patricia Gallagher. We showed her all that we had, including a Gamay Beaujolais which she thought was extremely close to Fleurie in Beaujolais. I was very happy with her response to all that we were doing. I liked my wines, but it's important to have someone who has some influence with consumers like them also and she may have been one of the first to visit with some knowledge of French wines and with the affirmation of her judgment brought pleasure. I'm just guessing that she was on a scouting expedition. It was actually her idea to have this tasting.

That she had a friend in Napa was convenient for her ability to come here and get the recommendations of Finigan, to scout around for the tasting and the event of the bicentennial that was being celebrated that year, and to make some publicity for their school and their shop and their restaurant. I think it was she who suggested to Spurrier that such an event would produce some benefit for their commercial endeavors of which she had been a part.

That was smart.

She must've gone back after she paid her visit to the Valley and visited with us and others. She must've gone back and said, ‘Steven, you have to go there yourself and see what is going on. You can't imagine the quality that's being produced by certain wineries in the Napa Valley. It's extraordinary. I think this idea will go over because they're certainly matchable with the things that we're looking for in quality wine.’ I don't think the full blown notion ... according to Steven Spurrier, they didn't actually formulate the notion that they should have the French wines, as a comparison, as a land mark, as a beacon, as a ...

Benchmark?

Benchmark. That's a little bit hard to believe that it was only later that the idea of benchmark ... Then why have it blind if it's a benchmark?

Anyway, that's to be unraveled at some future date. Some of this is speculation on my part, so you have to take it with a grain of salt.

I believe you.

That's how the wines were chosen. When he came here, he bought the wines and paid full value, and as I recall, and then may have made a trip around to get other wines that he wanted to have in this tasting in Paris. He did go down to the Santa Clara area and he got a bottle of Ridge. He did get some non Napa Valley wines also, so he made a wide sweep. I'm guessing she may have done the same thing, or others may have recommended to him the wines that he might be interested in for this tasting. That's how they were acquired, and then the question of how to get them to Paris, and all those details are in the book, George Taber's book.

I think he got Joanne Dickenson [to help get the wines to Paris]. Dickenson was having a tour being put together, and André Tchelistcheff was a part of that tour, of tennis and wine, and they were visiting wineries, and that was her professional business at that time, to set up tours for various places and to get people together, and there were quite a few vendors in that, touring wine country.

Your wife told you that you had won, right?

Yes, she did.

You were in Chicago at that time?

Yes I was.

You were taking care of your parents' estate?

Yes, and Chicago is the place where I first heard the bubbling of fermentation in my father's winemaking efforts with fruit wines and honey wines, and all of this was permitted during Prohibition. Do you remember? A head of household could make up to 200 gallons of wine for household use, not for sale, and he made wine at that time. That's when I put my ear to a cask. So all of this made a very nice ... When you think about it, why was I in Chicago to get this news?

Your dad made wine. I didn't know that.

My name means wine maker's son.

That's incredible. You were living in Chicago. You and Barbara decided that the kids should be in the rural area, so you got out ... In '64, that was pretty rough in Chicago. That was pretty rough in most urban areas. I grew up in the segregated south, and '64 was a tough year racially. When you were looking to go to another place, you decided not Napa first, right?

I was exploring. I went to New Mexico along the Rio Grande Valley. My academic background would not provide for a life that was supportable, and so we wanted to be part of an agricultural endeavor.

Your wife called and told you that you won. What was your reaction?

My reaction? Dorothy, I didn't know. It was a tasting. That's all I knew, there was a tasting in Paris. It's nice to have a tasting in Paris where you win. It's nice to have a tasting in West Paducah, Kentucky, where you win. It's nice to have a tasting in Los Angeles, New York, any place, where you win. I didn't know what wines were in the tasting. I didn't know it was a beauty contest. I didn't know who the judges were. At that particular moment, when Barbara got the call from Dorothy Tchelistcheff who had just returned from that tennis ... the Tchelistcheffs] were on that tour. That's how Dorothy brought the news back from France, when she and André returned themselves.

That's amazing. So when you did learn the repercussions of that win, what did you think?

I thought this is really something. I called it a Copernican moment. Nothing was the same after that. We looked at what we could do with different eyes, and so that Copernican moment changed the way we looked at things. It certainly changed the way I looked at things. I felt more responsible. I felt more responsibility to do the best and to be unlimited by any artificial barriers to achieving beauty in the wines that I was making.

That's beautiful, Warren. So suddenly you had the weight of America on your shoulders, American winemaking.

I wouldn't put it maybe in those terms. I had more responsibility to the fruit that I had. I had more responsibility to try to bring out the best in the fruit and to make it as perfect as possible. Then there were fringe responsibilities as you put it, but the first thing was the fruit, and the place, and the whole world that exists in that relationship.

That’s a fabulous way to look at it. So then what did you do? How did you go about doing that?

I had to be more alert. I had to be more perceptive to what the fruit was saying and every year it's a little different. To eke out the greatest amount of the last ounce of perfection that you can get, you have to be watchful. You have to be sensitive to what's going around, what's happening around the grapes’ evolution in that particular year. There were three ... In the course of a cycle of the sun, through the seasons, the vine is adapting itself and adjusting the resources that it puts into its vegetative phase, namely making leaves and shoots, extension of its shoots, and then making leaves to support not only its annual life, but its life as a perennial.

There are things about the plant that have to do with its contribution to one cycle of the sun, so those things live for only one cycle, leaves. Shoots can convert to live for many cycles of the sun. And then there's a berry, which only lives for one cycle of the sun. But inside the berry, there is that part, which you don't see when you look at the berry, which longs for eternity. The plant is always adjusting its own existence, to enhance or to give energy to those three demands, serving the three demands that multiplex, multi-faceted set of demands.

Being perceptive to those changes in the plant gives you the opportunity to respond to the outcome which you as the wine maker have to keep in mind, and to do what you can to bring out that part, which is going to help you in expressing the best you can, the most perfect expression of that year from that plant, or those plants in your vineyard which are responding in their own way to weather, to changes in humidity, to all of those things which have to do with the environment, but also to its internal adjusting and redistribution of its energy to those different phases. That all is going to make a difference to what you have in the end, which is only the attractant. That sugar, and that beauty in the fruit, is only an attractant to make animals such as us interested in a plant's life.

That's beautiful, Warren. Some people would have been paralyzed after the tasting. They would not have known what to do after that. They would've done stupid things but it seems like it made you more respectful and reverential toward the raw stuff that you were working with.

That's what I meant by the responsibility. There's this beauty there, and you may have been a little presumptuous in the beginning, and now you have to be more alert to the opportunities that are available to you, to get those beauties to come out. That's what I meant by the responsibility.

I get it.

That's related to that Copernican moment, where you look at things differently than you did before. You have the opportunity to look at things differently.

Looking back at that win this many years out, you’re going to be celebrating it again in May, have your feelings about that responsibility changed? It doesn't sound like they have.

I'm now only a grape grower, but I look at the grapes that I grow in the same way, but I don't have the opportunity in the winery to respond. So it's a little different, but I think about the grapes that way, but that was an outcome of those tasting then, this Copernican moment, as I can call it, changed the way I looked at things and gave me not only more motivation and aspiration, but more responsibility.

Do you remember that '73 harvest, what was stunning about it? Did it seem stunning to you?

The vines were young, obviously, and there was not a problem, in California with its abundance of sunshine and abundance of good weather, its bountiful rainfall, in '73. You had young vines, not old vines, which tend to want to outgrow the space that you give them. They had plenty of room, and these grapes were well exposed. The leaf canopy was not excessive. As I recall, it was a very good year with respect to the distribution of rainfall and the growing season itself. At harvest time, Andre walked through the vineyard with me. I think I say this in the book if I'm not mistaken. I was a little worried about choosing the harvest date, so Andre came by and Dorothy, and we walked through the vineyard, and Dorothy and I stayed behind. Andre walked a little bit ahead of us, and he was picking at the grapes from the clusters and tasting, and he made some remark about honey, divine honey, and I embraced Dorothy, hearing those words, and I knew we were at about the right time for harvest.

That was a magical moment. Everything went into high gear.

Yes, I think in '72 it was my partners who had harvested a little crop that we had. In '73, I think we had a crew. We had a commercial crew, professional crew, which means they were paid for the work that they did, and the partners were not. Partners were entertained. They kept all their fingers.

That's a good thing that they didn't lose anything. As word of your win went through your neighbors ‘ homes, how did they respond?

My neighbor was Nathan Fay, because his land adjoined. When I tasted Nathan Fay's '68 homemade Cabernet, '68 was a very fine year, and many people who tasted Nathan ... Nathan Fay was a very diligent, scrupulous, and perceptive wine maker, and his wine was good.

His wine convinced you to turn away from the Howell Mountain vineyard and to plant next to him.

Yes, correct. And to buy the prune orchard adjoining his vineyard, which happened to be for sale.

That's great, so everything lined up for you.

The moral of that story is never underestimate what you can do with a prune orchard.

You are wonderful! You never know, you never know. Well I read somewhere that you said that this win opened up opportunities. It gave you courage.

Yes. That also goes with the responsibility, but the courage, more of an incentive. Someone told me recently, since I didn't hear it myself, it's hearsay, that Catena had some similar feelings about the opportunity in Argentina, and George Taber, I'm sure. George Taber I don't know if he talked about this in his book in particular, but other people said it gave them confidence... What they did in California we can do here, too.

I read that the Smithsonian has an archive on your cellar. Does that mean they have library wines of yours?

There's only two bottles of wine in the Smithsonian. They don't have any library wines. They have records. They have photographs. They were here for about a week, in Chicago. One is the Chardonnay and one is the Cabernet, because they're icons. You used a better word. They're benchmarks for American agriculture.

The importance of them being in an exhibit that has to do with food is very significant.

That's how it is now. It's a food exhibition, which I believe is being extended again. The evolution of how food is understood on the American landscape, how food has grown in its capacity to express the social life of United States, and how it's changed over time. That's a very interesting exhibition, by the way, that food exhibition, and what part Julia Child played in it, as well as the time that coincided with the Paris tasting era. The interest in food and the interest in wine have a similar path, have a parallel path.

It makes the point that you should enjoy wine with food.

We wanted to support the Smithsonian’s interest in that, and to give them some resources to make possible the collection of things, and the development of that theme in American history, which came late, but came. The West came to be known, and acquired not only the reputation, but the actuality of what they were doing at a much higher level than it was done before, and competing with the world's great chefs in competitions and also entering into that phase of wine making at the same time. Wine and food together, and we wanted to support that development and institutionalizing of its place in American cultural history.

Are you the only financial supporter of it?

No, no. There are other people that do it as well. What we did for Ellis Island, we did similar kinds of things to support their activities, because even though my ancestors did not come through Ellis Island, they came through one of the other ports of entry, Ellis Island became the icon, the iconic representative of all those ports where immigration took place in the last part of the 1800s.

You owned the business a long time, and then you served on the board of directors of Ellis Island.

Yes, I was on the board for 14 years.

Tell me about working with Robert Mondavi. He must've been an amazing person to work alongside, a big personality.

Yes. He was a very energetic person whose energy infused others and gave them strong motivations to do for wine what ... To achieve for wine what his vision was: that it would become more widespread use, because all the potential and the activities that were occurring inspired him, and he inspired others. He'd been called Quicksilver by André Tchelistcheff.

I never knew that. I guess he had a quicksilver type of mind. That's very flattering.

He was a very energetic and inspirational figure with the energy that he ... Like I said, he himself was inspired, and he inspired others.

I imagine he was difficult, and a lot of people who do these things are. That's part of their makeup. Did you find him that way?

He didn't take halfway for an answer. He was not satisfied with half the loaf, and you could say he ... The stoics thought that happiness came from wanting less, but Robert Mondavi believed that happiness came from wanting more, so it was antithetical to the stoics way of thinking.

People who achieve big things, I think they have that in common. If they're not satisfied with having less, then they keep striving.

The future is a field for dreams.

If you were starting out today, who would you want to work with maybe? Is there someone who's doing something that you think you could learn from?

I'll tell you what's interesting today is the people who are looking back into varieties that have not been selected for a big opportunity to make great wines, and those are folks like Steve Matthiasson. You know him and what he's doing? [Matthiasson and his wife, Jill Klein Matthiasson, make Ribolla Gialla, Tocai Friulano, Refosco Dal Peduncula Rosso and other varieties that hail from Italy and are rare in this country.]

Yeah. They're exploring so to speak through a back door, which is always very interesting. I always like to know what hobby winemakers are doing with a variety. Because then you see underneath the skin, so to speak, of the winemaking activities into those who are making their first furrow into wine making, and you always find things in that first furrow that you have forgotten or that have been lost along the way because they're starting from an archaeological endeavor. They're coming under the skin and looking for things. The things they find they're not always looking for. They're not aware. Their simplicity turns over, turns up, things that you might have missed.

I always was very interested in hobby winemaking activities with the varieties that I was interested in, and that was all revealing what the veneer no longer revealed to me. I think these folks who are going back into varieties which have not received the attention that the so-called great noble five have received, I think they will turn up things. I would be interested in that, not perhaps as a primary interest, but as a subsidiary interest. It's like painters going back to create their own paints, their own tones, their own materials, their own structures. In that way, it revealed something about the art, and it revealed something about the material you're working with. That's useful to know if you're going to master your discipline.