In 1964, my family drove from Florida to see the New York World’s Fair in Queens. Its theme was “Peace Through Understanding” and it was dedicated to “Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe,” which sounds like something that the young Woody Allen worried about in “Annie Hall.” My best memory of the fair was of seeing Pietà, Michelangelo’s magnificent sculpture of Mary holding the body of her son Jesus after he was crucified. Michelangelo carved this 5-foot, 8-inch masterpiece, the only sculpture he signed, from a single block of marble. It reverberates in me still. How did he look at that single block of stone and see what was possible, see the Pietà?

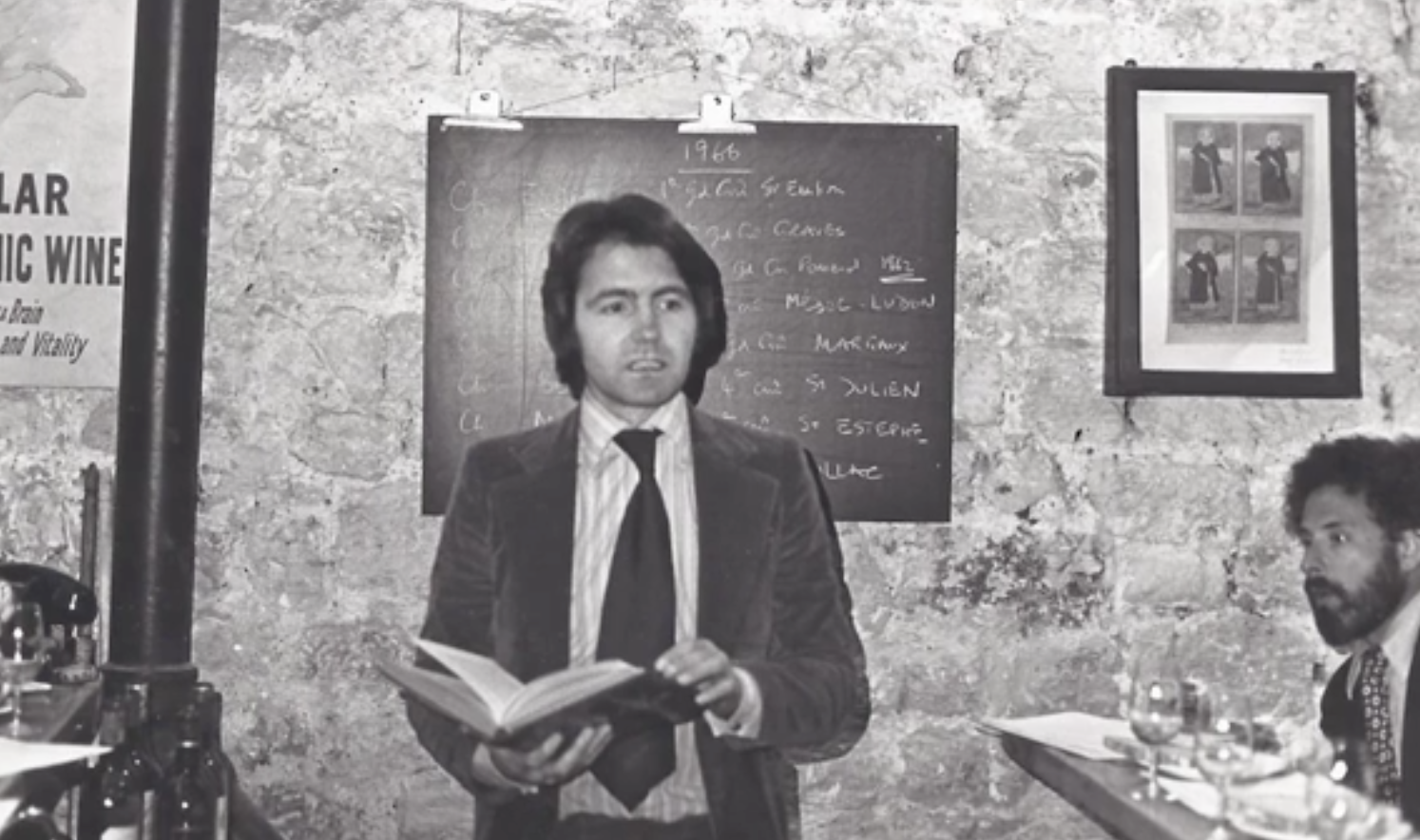

What got me thinking about that sculpture was a discussion I had recently with Warren Winiarski. He made the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon that French judges in 1976 rated in a blind tasting superior to all of the red Bordeaux before them. The judges also decided that a 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay that Miljenko “Mike” Grgich made was superior to all of the white Burgundies they had tasted. May 24 marks the 40th anniversary of what became known as The Judgment of Paris. It was arranged by Englishman Steven Spurrier (photo below) and his American assistant, Patricia Gallagher, and shook the wine world to its foundation because it announced, writ large, that Americans in Napa Valley were making wines equal to and better than the French. That stunning outcome also shored up the courage of winemakers in other countries.

Winiarski and the Smithsonian, which has a bottle of each of the 1973 winners in its “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000” exhibition, are sponsoring two sold-out events in May. Spurrier and George M. Taber, the only journalist who covered the tasting and who later wrote a fabulous book about it, will join others connected to the event at the dinner on May 17. Violetta Grgich will be there representing her dad, now 92.

Given raw stuff -- marble, grapes, whatever -- how does one sense its highest potential? Then, having sensed it, how does one proceed with the confidence necessary to pull it off, but with enough humility to know that one false move and you’ve got a pile of rubble or a just good-enough wine? Over about two hours on the telephone in two conversations, Winiarski and I talked about whether it was inevitable that an upstart region’s wine would best the French. In a word, yes. He also told me, among many other things, what he thinks the French were thinking when they tasted his wine.

Perhaps Winiarski, 87, was destined to make that historic wine. His last name, in Polish, means son of a winemaker, he told me, and his father, Stephen, did indeed make wine in their home in Chicago. Winiarski was in that home in Chicago, dealing with the affairs of his mother’s estate, when his wife, Barbara, called to inform him of his win. Destiny?

What was his reaction to the news? “That’s all I knew, there was a tasting in Paris,” he told me. “It’s nice to have a tasting in Paris, where you win. It’s nice to have a tasting in West Paducah, Kentucky, where you win. It’s nice to have a tasting in Los Angeles, New York, any place, where you win. I didn’t know what wines were in the tasting. I didn’t know it was a beauty contest. I didn’t know who the judges were.”

So when you realized the repercussions of that win, what did you think?

“I called it a Copernican moment,” he said. It helps here to appreciate that Winiarski is a scientist, philosopher, poet, eternal student and lecturer for decades at his alma mater. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) was a genius who proclaimed that the Sun, not the Earth, was at the center of the universe.

“Nothing was the same after that. We looked at what we could do with different eyes, and so that Copernican moment changed the way we looked at things. It certainly changed the way I looked at things. I felt more responsible. I felt more responsibility to do the best and to be unlimited by any artificial barriers to achieving beauty in the wines that I was making,” Winiarski told me.

Suddenly it must have seemed as though he, and of course Grgich, too, had the weight of the American wine industry on their shoulders, I ventured.

“I wouldn’t put it maybe in those terms,” Winiarski said, gently waving me off. It was the raw stuff, the marble, the grapes.

“I had more responsibility to the fruit that I had. I had more responsibility to try to bring out the best in the fruit and to make it as perfect as possible. Then there were fringe responsibilities, as you put it. But the first thing was the fruit, and the place, and the whole world that exists in that relationship.”

So then what did you do? I wanted to know.

“I had to be more alert. I had to be more perceptive to what the fruit was saying and every year it’s a little different. To eke out the greatest amount, the last ounce of perfection that you can get, you have to be watchful. You have to be sensitive to what’s going around, what’s happening around the grapes’ evolution in that particular year.”

While a graduate student spending a year abroad in Italy, Winiarski had become smitten with the everyday mealtime pleasures of wine. Back in Chicago, he and Barbara decided they wanted an agrarian way of life for their family, so he moved to Napa in 1964, where he worked at Chateau Souverain and later the new Robert Mondavi Winery. He left that job for another for which he selected California grapes that were then sent to Denver to be made into wine there, acting as midwife to the Colorado wine industry.

Stag's Leap Wine Cellars

In Napa, Winiarski had set his sights on a parcel of land when he happened to taste a homemade wine from grape-grower Nathan Fay. Fay’s Cabernet Sauvignon hit Winiarski’s sweet spot and as luck or destiny would have it, there was a prune orchard next to Fay’s land that was for sale. The Winiarskis pounced. (“And the moral to that story,” he joked, “is never underestimate what you can do with a prune orchard.”)

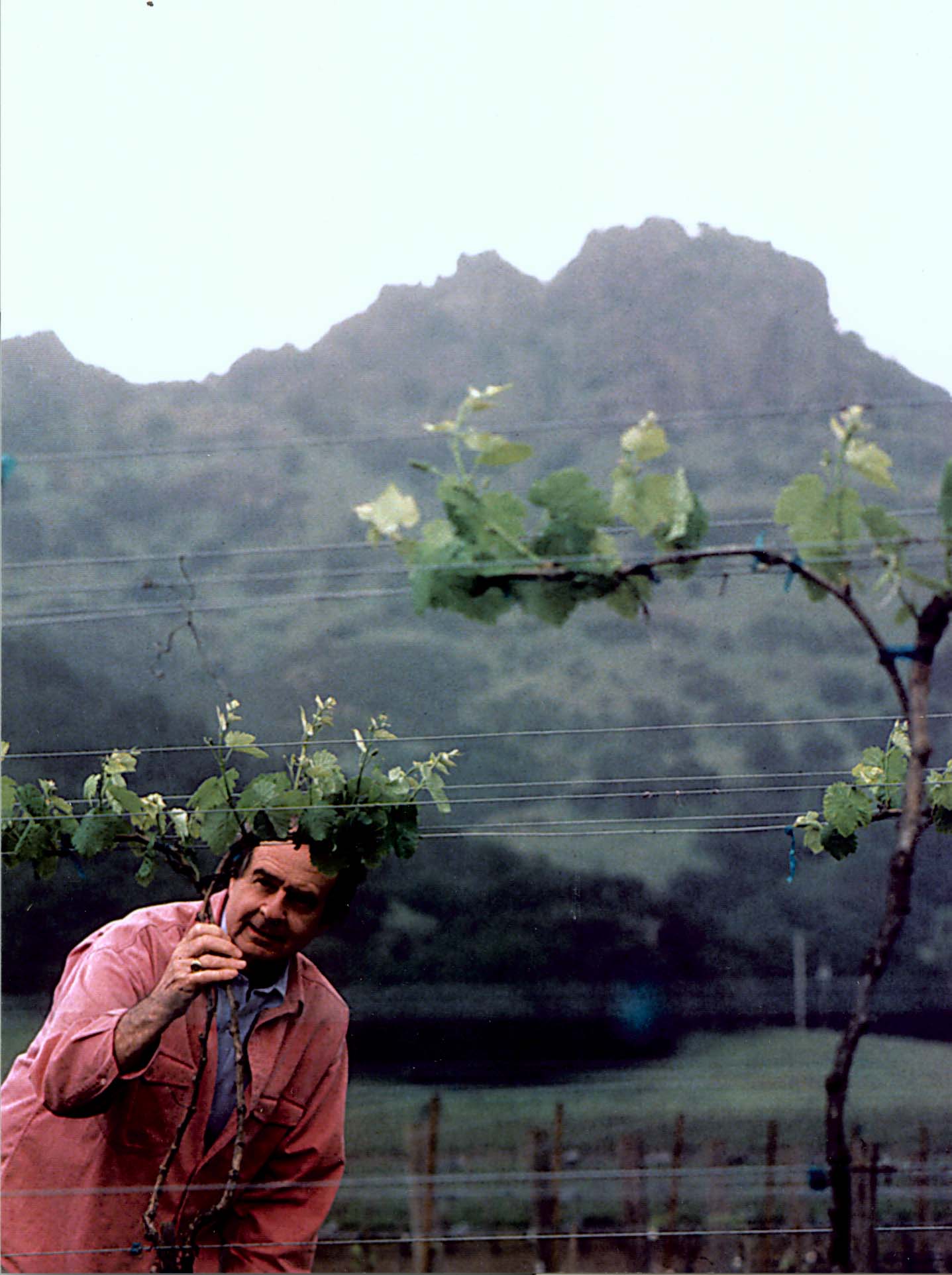

In 1970, they planted the land to mostly Cabernet Sauvignon and some Merlot—there was some Petite Sirah already there-- and made their first wine from it, in 1972, at a friend’s facility. The 1973 that topped the French judges’ scorecards was only the second wine Winiarski made from his grapevines, which were then only three years old, and it was the first wine he made at his own new winery.

The Winiarskis were close to André Tchelistcheff, who has been called the most influential post-Prohibition winemaker in America, and his wife, Dorothy. The Tchelistcheffs had been in France at the same time as that fateful tasting and it was Dorothy who had called Barbara to share the news. Tchelistcheff mentored many of the pioneering greats in Napa from his perch as winemaker at Beaulieu Vineyards, where he crafted spectacular Georges de Latour Private Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon. (In 1992, Tchelistcheff signed the label of the 1968 we’d had on our honeymoon in Napa.)

Tchelistcheff, according to Taber, had called Winiarski “one of the best winemakers in the Napa Valley, maybe even the best.” He was taken by the fact that Winiarski “minutely watched over each step of grape growing and winemaking, hovering over every row of vines and every barrel of wine.” In 1973, Tchelistcheff became a consultant to Winiarski.

“I was a little worried about choosing the harvest date, so André came by and Dorothy, and we walked through the vineyard. André walked a little bit ahead of us, and he was picking at the grapes from the clusters and tasting, and he made some remark about honey, divine honey, and I embraced Dorothy. I said, ‘Hearing those words….’ and I knew we were at about the right time for harvest.”

The growing season had been perfect, the grapes were picked near a time Tchelistcheff had blessed. Now what to do? Where to strike with the chisel? What is the shape of the wine he wanted to make?

Winiarski refers to his elegant, layered wines as Goldilocks wines, “not too much, not too little, just right.” In his 2010 commencement address for St. John’s College, Annapolis, he put it this way:

“Wines that are too powerful destroy or mask the subtlety, finesse, and wonderful complexity that are present in wines of moderate alcohol. So I asked myself… ‘Where, in such powerful wine, is music – harmony, measure, limit, and number, ratio and proportion?’ The proper ripeness and therefore the proper balance must be a unique point. I asked myself how to find that point – where there is growing toward the proper balance on one side of it and a growing away from it on the other. I was looking for that point of noon. The wine that went to Paris in 1976 reflected my winemaking effort to find that point of limit and balance.”

He explained to me that “to be complete, a wine has to have three fundamental things. It has to have a beginning. It has to have a middle. And it has to have an end. If you don’t have the sensation of that because everything is in the beginning, then you don’t have the ingredients for perceiving completeness. What guided me in my thinking about winemaking was trying to achieve that sense of completeness, and I think the French tasters may have believed that they were tasting a French wine when they were tasting mine.”

In 1976, the results of the white-wine tasting were tabulated first and announced by Spurrier. “When he finished, Spurrier looked at the judges, whose reaction ranged from shock to horror,” Taber wrote in “Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting That Revolutionized Wine.” On to the reds. “The French judges, he felt, would be very careful to identify the French wines and score them high, while rating those that seemed American low.” Again, Spurrier announced the results and a California wine, Winiarski’s, had come out on top.

The French did not take it well and none will be at the Smithsonian in May. Taber wrote that in the many reenactments that followed, “the results have been surprisingly similar to the original” though most were done with American judges “who were not always wine experts.”

In 2007, with his children wanting to do other things, Winiarski sold Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars on the Silverado Trail and focused his attention on a Chardonnay vineyard he had purchased from Grgich, who had long ago left Montelena and made stellar Chardonnays on his own at Grgich Hills Estate in Rutherford. Winiarski named the vineyard Arcadia. He only grows grapes there and no longer makes wine.

Do you miss winemaking? I asked him.

“I do,” he replied.

It’s so hard to imagine you walking away from it, I said.

“I found it difficult to imagine it also,” he replied.

So, I said, you grow the grapes and then…

“I think about the wine, where these grapes could be destined.”He said.

Is that enough? I asked.

“It is at this time,” he said.

Any regrets? I asked.

“Regrets are attachable to alternatives,” he told me, “but it was the best thing to do … at the time.”

Dorothy J. Gaiter conceived and wrote The Wall Street Journal's wine column, "Tastings," from 1998 to 2010 with her husband, John Brecher. She has been tasting and studying wine since 1973. She has had a distinguished career in journalism as a reporter, editor, columnist and editorial writer at The Miami Herald and The New York Times as well as at The Journal.

Read the full interview with Warren Winiarski here.