The sensory allures of German Riesling are immediate: sublimely aromatic, electric in their acidity, endowed with Edenic fruit flavors and unrivaled for their lithe, mineral refreshment. Understanding the wines, on the other hand, can be a life’s work. This noble grape gives a range of wines that run from racily dry to lusciously sweet, the best of which eloquently translate terroirs as diverse as the limestone and loam of the Pfalz and the blue and red slates of the Mosel.

The challenge German Riesling presents is coming to grips with the stylistic complexity many would argue is its raison d’etre. “Riesling is so digitally precise, so finely articulate, so pixilated and pointillist in detail that other wines seem almost mute by comparison,” argues writer and importer Therry Thiese. Much of this detail complicates German Riesling labels. You don’t actually need advanced degrees in linguistics, history, geography, and enology to fully understand the baroque labels that decorate some bottles. But it sometimes feels this way. New York Times wine columnist Eric Asimov flatly concedes that understanding German wines is “hellishly difficult.” But he, and every other Riesling lover, acknowledge the pursuit is “worth it.”

A little background may help. Winemaking in Germany dates to Roman times. The rise and fall (and rise again) of German Riesling in many ways mirrors European history. The most esteemed producers, families who in many cases have been making Riesling for centuries, consider their labels proud, inviolate manifestos of tradition, practice, and place. But in 1971, Germany’s vinous landscape was literally redrawn by the sweeping German Wine Law. France was then leading the way with new appellation systems and quality controls. German legislators sought to protect their nation’s vinous patrimony and to shore up crucial export markets with new labelling requirements. Ever since, the German Riesling label has been something of a battleground between lore and law.

A little background may help. Winemaking in Germany dates to Roman times. The rise and fall (and rise again) of German Riesling in many ways mirrors European history. The most esteemed producers, families who in many cases have been making Riesling for centuries, consider their labels proud, inviolate manifestos of tradition, practice, and place. But in 1971, Germany’s vinous landscape was literally redrawn by the sweeping German Wine Law. France was then leading the way with new appellation systems and quality controls. German legislators sought to protect their nation’s vinous patrimony and to shore up crucial export markets with new labelling requirements. Ever since, the German Riesling label has been something of a battleground between lore and law.

Ironically, what’s often lost in the fray is the one piece of information consumers want most: Will the wine be sweet or dry? German Riesling’s long history and diversity of terroirs, a trend toward warmer vintages and the vagaries of vinous fashion have pushed the sweetness scale forward and back, leaving countless drinkers to wonder how to know what to expect when they uncork a bottle.

Many have tried to zero in on a simple method for identifying a Riesling’s sense of sweetness (or “style,” as its known) based on label alone. Even the experts acknowledge it can be a humbling task. But here are five basic rules that should steer you to a German Riesling that’s precisely calibrated to a very specific palate: yours.

Trusty terms

These words and abbreviations are not mandated, but if you find them on a bottle, they’ll help.

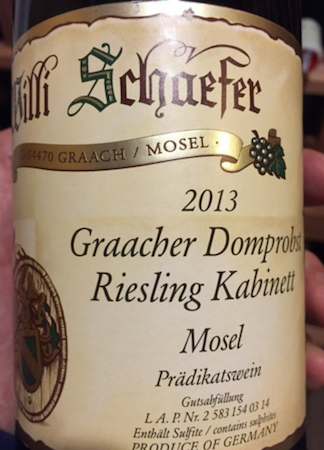

Trocken = bone dry; Halbtrocken = dry tasting; Feinherb = off dry; Kabinett = lightly sweet; Kabinett Trocken = dry; Spätlese = fully sweet; Auslese = fully sweet, honeyed; Beerenauslese/Trockenbeerenauslese/Eiswein = without exception lusciously and exuberantly sweet dessert wines; GG or EG = fully dry, only made by top producers from “grand cru” or “premier cru” parcels.

ABV: If it’s high, it’s dry

When grape juice is fermented into wine, yeasts turn the sugars in the juice into alcohol. For a sweeter wine, a winemaker will stop fermentation while the wine still has what is known as “residual sugar.” For a dry wine, a winemaker will let the fermentation run to completion, meaning all of the sugars have been converted into alcohol. So, a dry Riesling is one that has had all its sugars fermented into alcohol, producing a correspondingly higher level of alcohol by volume (ABV). Use these guidelines:

7.0-8.5% = fruity/sweet

9-10.5% = off-dry

11-14% = dry

Acid rules

The reason Rieslings can get away with so much residual sugar in the sweeter wines without being syrupy or cloying is the razor’s edge of acidity that is the variety’s other hallmark. Unfortunately, total acidity levels are rarely stated on German Riesling labels. However, it is generally safe to assume that quality producers will have struck a balance between acid and sugar that drives forward the gorgeous stone fruit, citrus and tropical fruit flavors Riesling abounds in, while checking perceptible sweetness.

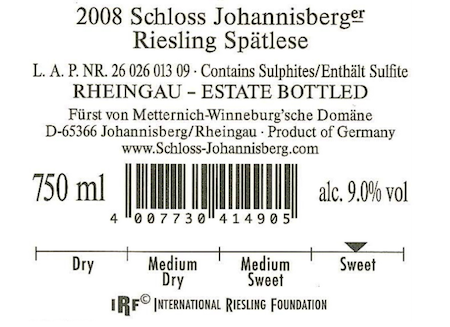

(Caption: Schloss Johannisberg is one a small number of German producers who have adopted the IRF Riesling Taste Profile scale. You might already know that Spätlese is a sweet wine. Or you could just look at the scale.)

The older, the better

…if you like dry Riesling, that is. Riesling’s sense of sweetness tends to recede with age, especially in high-acid vintages. Bear this in mind, especially when reaching for a bottle from vintages such as 2010, 2008, 2004 or 1996.

You could get lucky

The International Riesling Foundation (IRF) has recognized the plight of would-be Riesling drinkers worldwide and come to the rescue with an at-a-glance indicator scale. Winemakers calculate the interplay of residual sugar and total acidity, then place an arrow on the scale that indicates the resulting sense of sweetness. You could get lucky and find this on the back of the next Riesling that comes your way. This scale has proven very popular: more than 30 million bottles of globally produced Riesling in the U.S. market now carry one on the back label. However, this practice has yet to be widely adopted by German Riesling producers. (German complexity in yet another form.)

Test your knowledge on these (and other) German Rieslings from Grape Collective:

Willi Schaefer Graacher Domprobst Riesling Kabinett 2015

Weingut Muller-Catoir Burgergarten "Im Breumel" 2015

Eva Fricke Lorch Riesling Trocken 2015

For a great deal more on deciphering German Riesling labels, see Mosel Fine Wines, Issue No. 34, April 2017